The 100 Best Albums of 2025

2025 didn’t need a single story to explain why the music hit. A year of returns, debuts, and sudden left turns. This list follows the records that made their own rules and didn’t back down.

An artist disappears for a while, then returns with a record that refuses to apologize for the gap. Another returns with a different voice, older priorities, and a sense of what matters now. 2025 was full of that energy, comebacks that didn’t try to recreate a past version of success. Some of the best albums sounded like people stepping back into the world with new rules. The year rewarded patience as much as speed.

Debuts mattered too. A first full-length can be a test, a statement, or a dare, and this year had plenty of artists who treated it as all three. Instead of trying to cover every influence at once, the strongest debuts picked a lane and dug in. That focus showed up in writing, in rhythm choices, and in the way collaborations were used. When a feature appeared, it usually served a scene, not a checklist. The albums felt built, not assembled.

This list is organized around that sense of intention. The page is one long scroll of titles and paragraphs, with cover art as a visual cue and bylines that remind the reader there was a person behind each pick. It moves fast, because the year moved fast, but the language keeps slowing down on the important moments. Not every album here will be a comfort listen. Every album here made its case.

Call it a year of refusal. Refusal to smooth the edges, refusal to let marketing language do the explaining, refusal to chase a single idea of what success should sound like. Those refusals came in different styles, but the shared thread was control. The artists knew what they wanted their records to do in a room. This list follows that impulse.

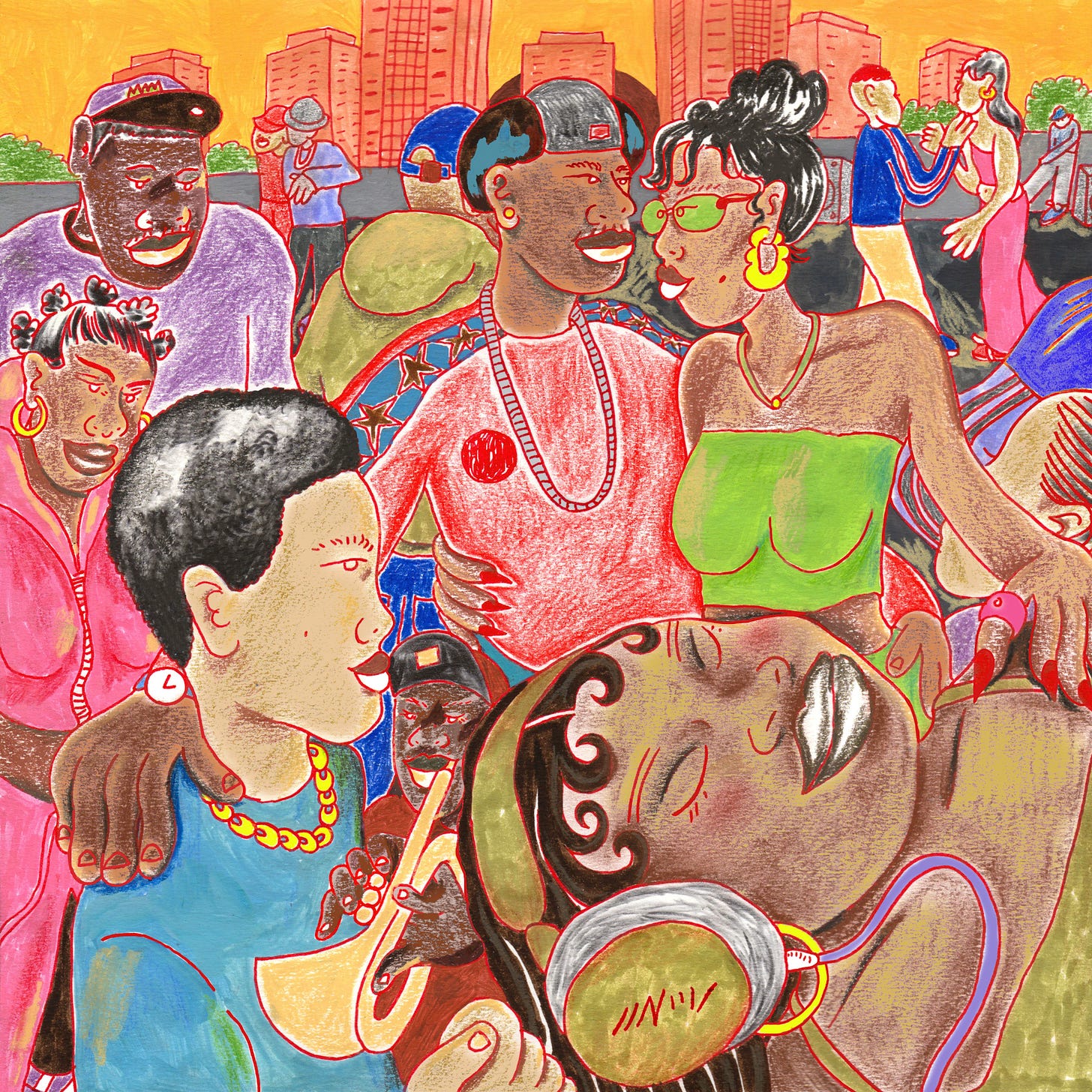

José James, 1978: Revenge of the Dragon

José James cut the entire set to two-inch tape inside Dreamland, a converted church whose wooden rafters trap cymbal spray and ambient hiss, so the record breathes like a crowded club rather than a DAW grid. BIGYUKI’s analog synths fizz against Jharis Yokley’s cracked-rim snare while a three-horn frontline of Takuya Kuroda, Ebban Dorsey, and Ben Wendel punches lines that feel lifted from a Shaw Brothers soundtrack. “Tokyo Daydream” drapes that brass over a rubber-band bass ostinato, then slips into double-time handclaps that evoke neon alleys at midnight. The Michael Jackson cover “Rock With You” slows to half-speed, James stacking his voice into woozy harmonies while a dubbed-out clavinet wobbles beneath muted trumpet. “They Sleep, We Grind (for Badu)” filters a clav groove through tape echo, echoing its mantra-like hook across speaker cones until it feels more ritualistic than a song. Original “Rise of the Tiger” rips forward with fuzz bass and kung-fu dialog samples, paying tribute to James’s own martial-arts practice. “Last Call at the Mudd Club” ends on a bent tenor-sax scream that fades into the studio’s natural reverb, leaving only creaking floorboards and tape hiss as the lights cut. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Joe Armon-Jones, All the Quiet (Part II)

Joe Armon-Jones handles writing, production, and mixing, fusing jazz harmony with dub atmosphere and easygoing funk grooves on his own terms with this sequel. “Acknowledgement Is Key” lets Hak Baker recount personal struggles over sparse keys and rounded bass, turning conversational snippets into central hooks. “Westmoreland” brings Asheber’s resonant baritone atop a rhythm inspired by sound-system culture, while analogue hiss signals Armon-Jones’s fondness for tactile studio character. Greentea Peng and Wu-Lu share space on “Another Place,” trading melodic lines that glide rather than clash. Yazmin Lacey’s appearance on “One Way Traffic” offers a brief lift before the band settles back into steady motion. Nubya Garcia threads short sax phrases through several sections, never overstaying. Drummer Kwake Bass locks a relaxed pocket that lets keyboard voicings float. Instead of chasing climaxes, Armon-Jones allows ideas to breathe, rewarding jazz fans who stay for detail. — Harry Brown

Sunny War, Armageddon In a Summer Dress

After her 2022 album Anarchist Gospel earned attention and tours with Bonnie Raitt and Mitski, Sunny War returns with her most full-band effort, working again with producer Andrija Tokic to marry her anarchic folk-punk sensibility with retro-soul arrangements that dress fury in beauty. “One Way Train” explodes immediately with no patience for slow builds, singing about a future where there’s no police or state, where fascists and class systems have burned away. The anger embedded in “Bad Times”—“I make the least you can in an hour, I’ve got no money, so I’ve got no power”—gets wrapped in danceable Tamla rhythms that create dissonance between message and medium. “Rise” urges living for the moment over choppy guitar licks, acknowledging the sun might not shine again. Steve Ignorant from Crass joins “Walking Contradiction” to deliver class war observations (”Your humanity does not outweigh your will to survive”), connecting War’s politics to punk lineages that predate her. Valerie June adds vocals to “Cry Baby,” and John Doe from X appears on “Gone Again,” both collaborations signaling War’s arrival as someone artists want to work with. “Scornful Heart” pairs with Tré Burt, building folk arrangements that sway rather than punch. — Tai Lawson

Olivia Dean, The Art of Loving

If you know about Olivia Dean, then you understand how quickly she’s grown. She pairs that familiar palette with diaristic songwriting as shown on Messy, but she deals with the mundane joys of new romance and the awkwardness of moving on from old love, her sweet, understated voice free of the crooner affectations that weigh down so much contemporary pop on The Art of Loving. On “Loud,” she lets her full voice soar over strings and a guitar melody reminiscent of Amy Winehouse and Adele, while “Close Up” turns intimacy into a whispered confession, accompanied by piano and horns. “A Couple Minutes” samples a 1971 guitar riff from Hot Chocolate and uses its groove to underscore the warmth of new love. “Baby Steps” embraces self‑love after a breakup, as Dean sings about being her own safe harbour and planting roses to celebrate her growth. The introductory title track frames the album as an exploration of what it means to care and be cared for, and “I’ve Seen It” promises that love is all around, concluding that it has been inside her all along, utilizing influences and writing with more detail and vulnerability. — Charlotte Rochel

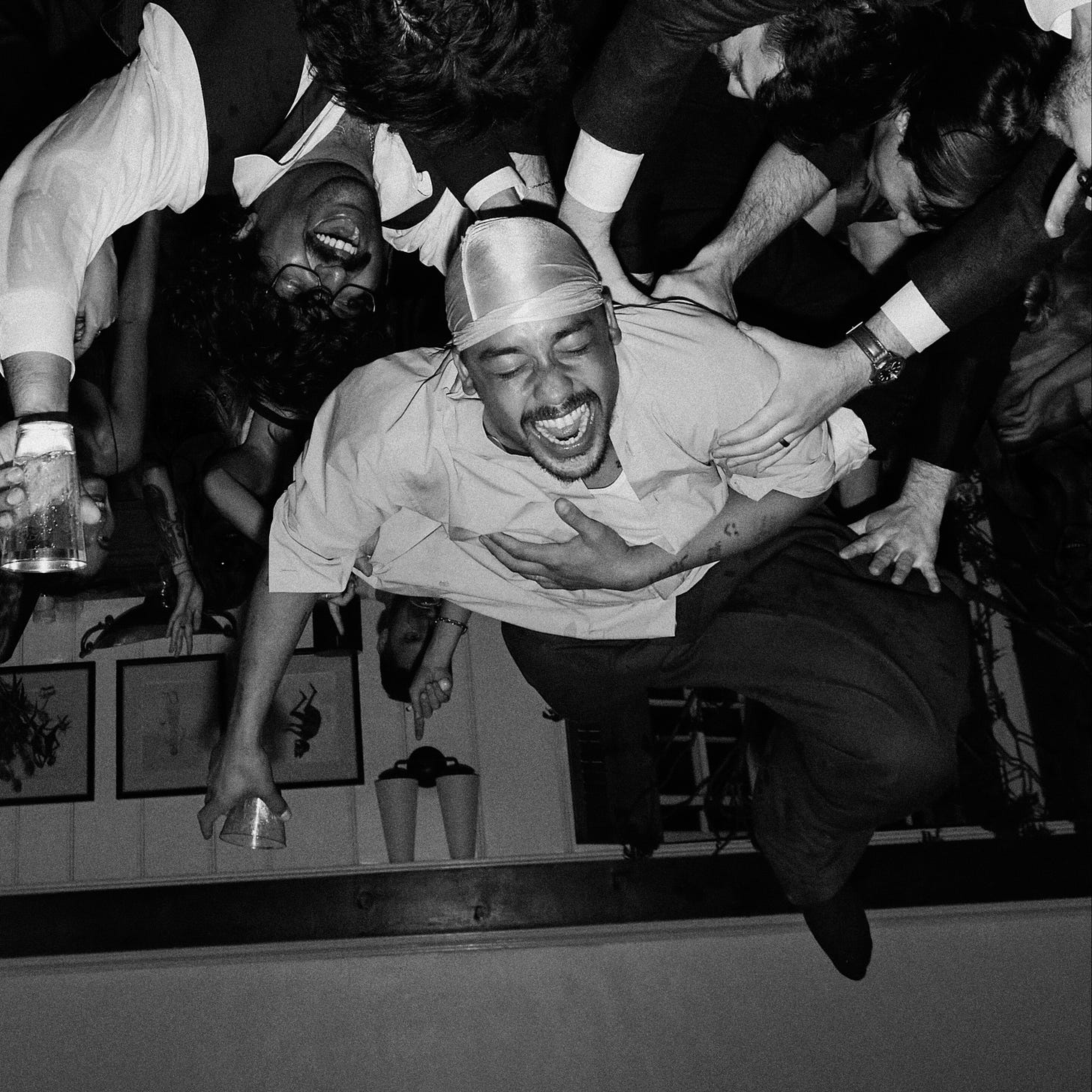

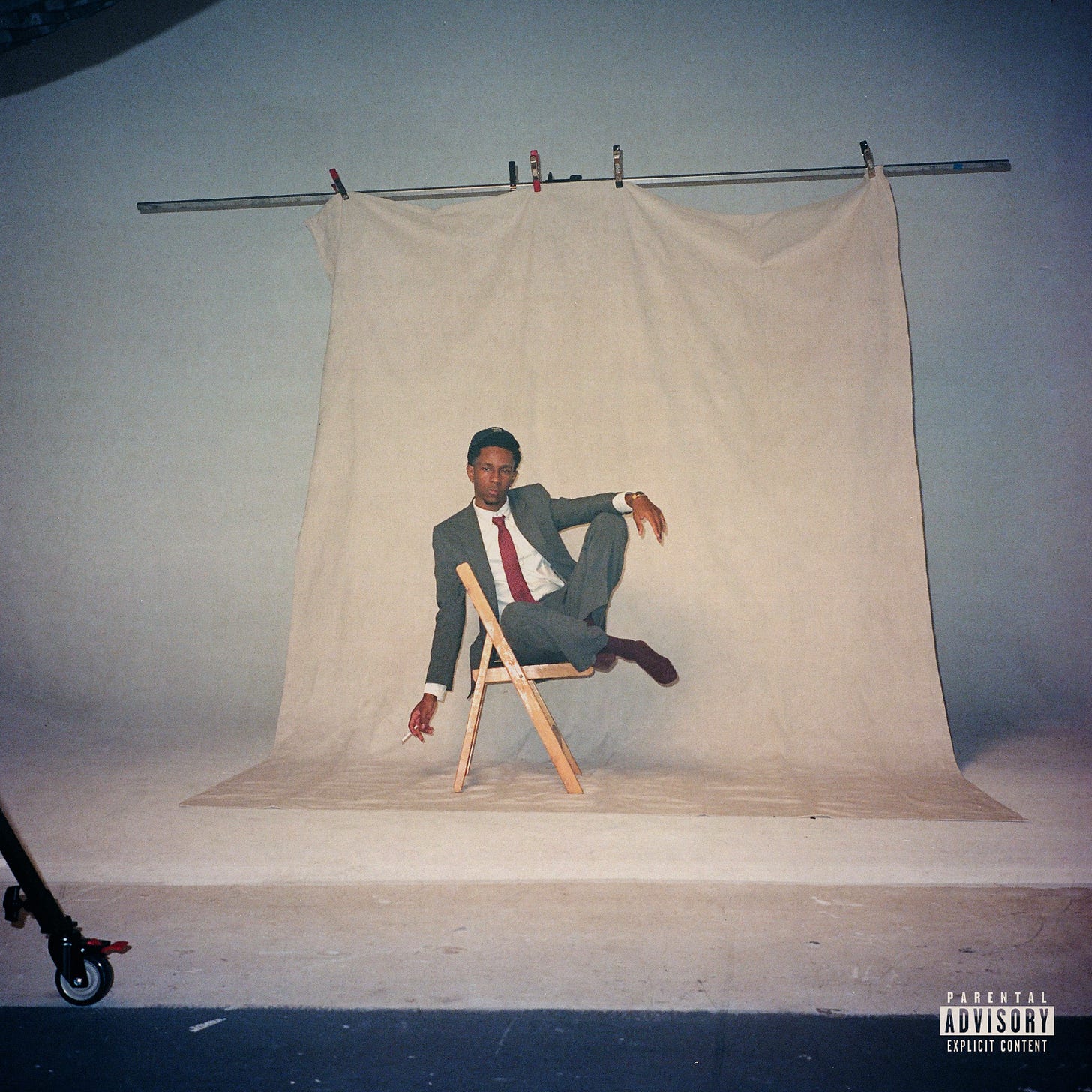

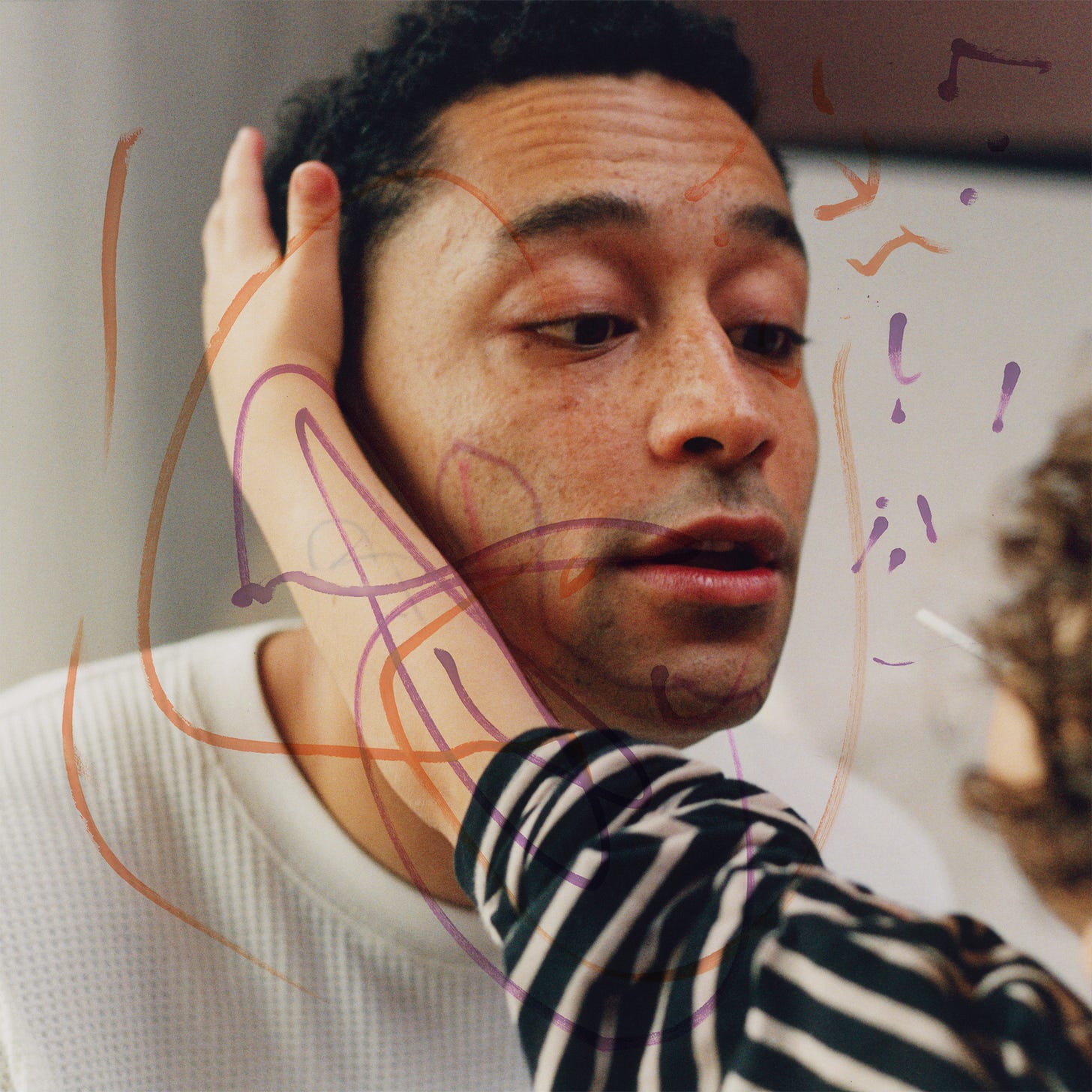

Dijon, Baby

After the hard-won leap of Absolutely, Dijon returns with a second full-length built to pressure test what comes next. He writes from the life he’s been building, partner and new father in the house, and he bends the record toward that pressure with a jumpy, collage-minded approach that treats memory and domestic noise as usable parts of the kit. Songs pivot on sudden cutaways, voices pitch and splinter, and the drums lurch from human swing to clipped fragments that feel sampled even when they are played, a method he sharpened with Mk.gee and BJ Burton and kept flexible with Andrew Sarlo and Henry Kwapis. The effect is a steady argument for intuition over symmetry. Hooks arrive from the side, a shout becoming a refrain, a breath turning into a cue. When he asks, “Is it all just patterns packed inside,” the question doubles as a design note, because repetition here is never quite repetition, and the lyric keeps the music honest about what love and panic can do to form. A track like “Another Baby!” moves like a quickening thought, synth stabs and vocal yelps ricocheting without losing the thread of devotion, while “My Man” wears bright R&B vowels over scuffed tape edges so the tenderness has grain to it. Even when the room gets loud, the writing stays intimate, naming ordinary rituals and doubts with the clipped attention of someone catching ideas between feedings. The album’s core is that lived-in speed, and a tight circle of collaborators, a comfort with messy takes, and a belief that a family’s daily weather can power a pop record without sanding it down. — Tai Lawson

DJ Haram, Beside Myself

DJ Haram channels fury into inventive hybrids on her first full‑length, drawing on club beats, heavy guitars, and Middle Eastern percussion to articulate what she has called being “beside herself” with rage over a violent world. “Lifelike” opens with an ominous synth drone and guitar feedback before her voice declares, “I see god, I can’t stand him,” setting the tone for an album that veers between despair and defiance. “IDGAF” juxtaposes sludgy metal riffs and hand‑clap rhythms with darbuka patterns reminiscent of a Syrian Black Sabbath, while “Badass” centers a chant over claustrophobic percussion. Elsewhere, the record folds in Middle Eastern house (“Loneliness Epidemic”), breakbeats that seem to spar with darbuka drums (“Sahel”), and a swaggering violin reminiscent of RZA’s productions on the posse cut “Fishnets.” Its refusal to sit still makes its cathartic release possible; anger and joy, protest and dancefloor bliss are layered rather than segregated, and that complexity leans into dissidence with her. — Harry Brown

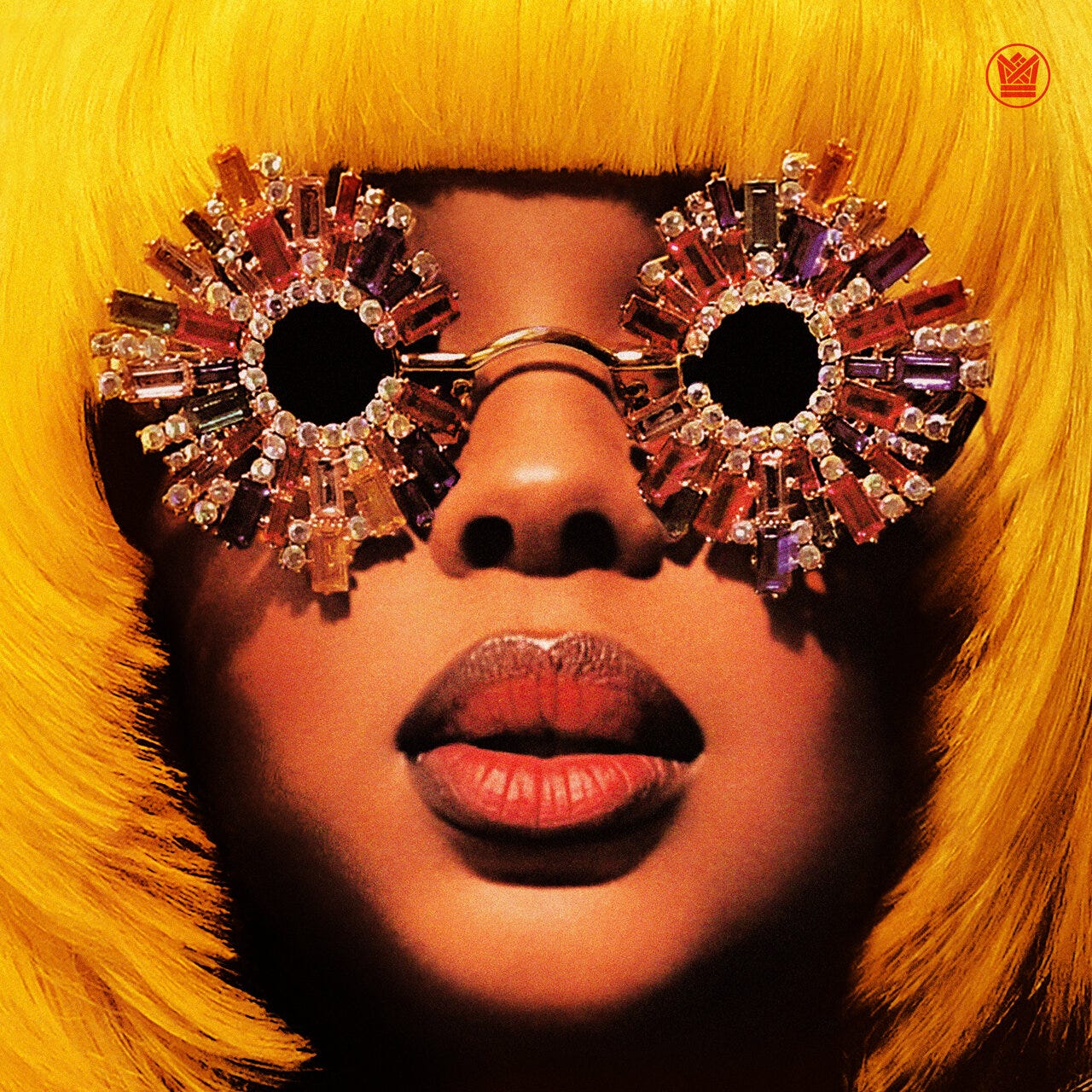

Amaarae, Black Star

Amaarae arrives here with real momentum. The Angel You Don’t Know turned a local cult into a global footprint, “Sad Girlz Luv Money” cracked the door wider, Fountain Baby proved she could build a world and tour it, then she stepped onto bigger stages as the first Ghanaian to play a solo Coachella set and leaned into the pop star she’s been writing toward. That’s why Black Star feels like the moment she chooses appetite as engine and writes directly to desire, control, and play. The songs are built for motion and face-to-face drama, switching between taunting invitation and delighted excess. “Starkilla” links Bree Runway’s bite to Starkillers’ club muscle, “Kiss Me Thru the Phone Pt. 2” pulls PinkPantheress into a sugar-wired techno sprint, “ms60” closes with Naomi Campbell’s cool poise as a statement of intent, and “S.M.O.” pulls on highlife ideas and swings with warmth, mixing sacred language with hedonist promise until the song reads like a ritual of consent and pleasure. She toys with pop memory, nodding to Cher and Gucci Mane while keeping the center of gravity in her own voice. She keeps everything playful, cutting, self-mythologizing, but specific about desire and power, which is why Black Star works as a portrait of power in motion, an artist testing how far clarity can go when pleasure is the subject and the pen keeps the rules. — Ameenah Laquita

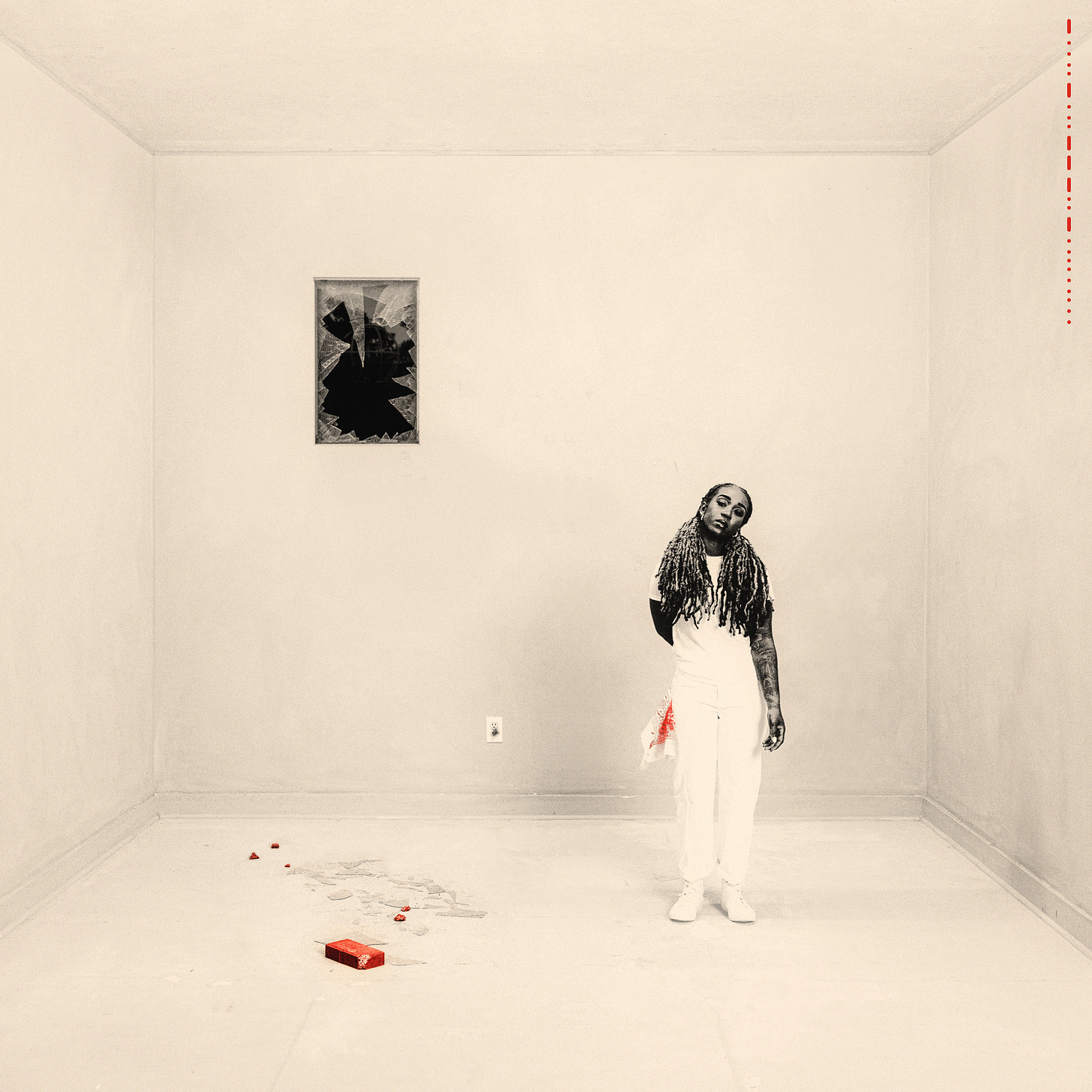

Jackie Hill Perry, Blameless

Jackie Hill Perry returned to hip‑hop after nearly a seven‑year hiatus, bringing with her the perspective of an author, spoken‑word poet, and mother. With Blameless, she built a conceptual “house” where each song occupies a room and together they form an examination of faith, the Church, and personal accountability. “The Home” invites us into that house by narrating a scene at a red house with a cracked window, knocks on the door, slips inside and wanders through rooms where greed and distraction lurk, and “Pride and Prejudice” she confronts her identity head‑on—“Indian in my blood/You can tell by the roots/Ain’t selling dream catchers/Everybody wanna be a prophet/‘Til it’s time tell the truth”—before the hook admits “Maybe I’m just relevant/Maybe I’m just arrogant/Maybe y’all need a therapist,” showing self‑examination and vulnerability. “I Ain’t Worried” finds her telling anyone who will listen that she doesn’t chase money or gossip, boasting, “Got four babies and they crazy call me Donda,” and dismissing online critics by saying, “Why you talking mess? It ain’t no flex to spin that gossip/When I spit that gospel.” Even the uplifting “Keep Your Head Up” carries depth; over bright keys, she urges weary women to look to heaven, reminding them that they are seated in heavenly places while cautioning against overthinking and self‑sabotage. Throughout Blameless, Perry knits theological reflection into conversational rhymes, blending admonition with encouragement to craft a record that feels like both a candid journal entry and a sermon in equal measure. — Murffey Zavier

Durand Bernarr, Bloom

Raised by two musician parents and homeschooled in a creative household, Durand Bernarr has always preferred communal music-making to solitary practice, and last year, he reached a turning point. The Cleveland-born R&B artist had built serious momentum with his En Route EP, a project that earned him a fresh wave of fans and a 2025 Grammy nomination. Bloom is a clear shift from his usual approach, born out of necessity and seeking fresh input. Bernarr leaned on collaborators like GAWD, featured on the upbeat “Flounce,” and b.kae, who co-wrote the lead single “Impact.” Songwriter Timothy Bloom and friend Bella Rose rounded out the crew by adding background vocals. The result feels like a tribute to all kinds of bonds: romantic, platonic, creative. The album’s strengths shine in its variety. On the shimmering 1990s throwback “No Business,” he chastizes himself for loving someone who doesn’t deserve it, admitting, “I ain’t got no business loving somebody else the way that I love you.” It contrasts sharply with “Unspoken,” a standout ballad that ranks among 2025’s best tracks. Even the playful duet “That!” with T‑Pain and the deeply personal closer “Home Alone” serve Bernarr’s larger theme—he sings about his parents’ unconditional love and finds solace in his own space, gratefully recalling how they “never once felt condemned, didn’t throw me away.” Bernarr’s choice to pivot, pulling in outside voices while keeping his core sound intact, shows an artist adapting under pressure. Bloom doesn’t reinvent R&B, but it proves Bernarr can stretch his limits and deliver something worth hearing. — Jamila W.

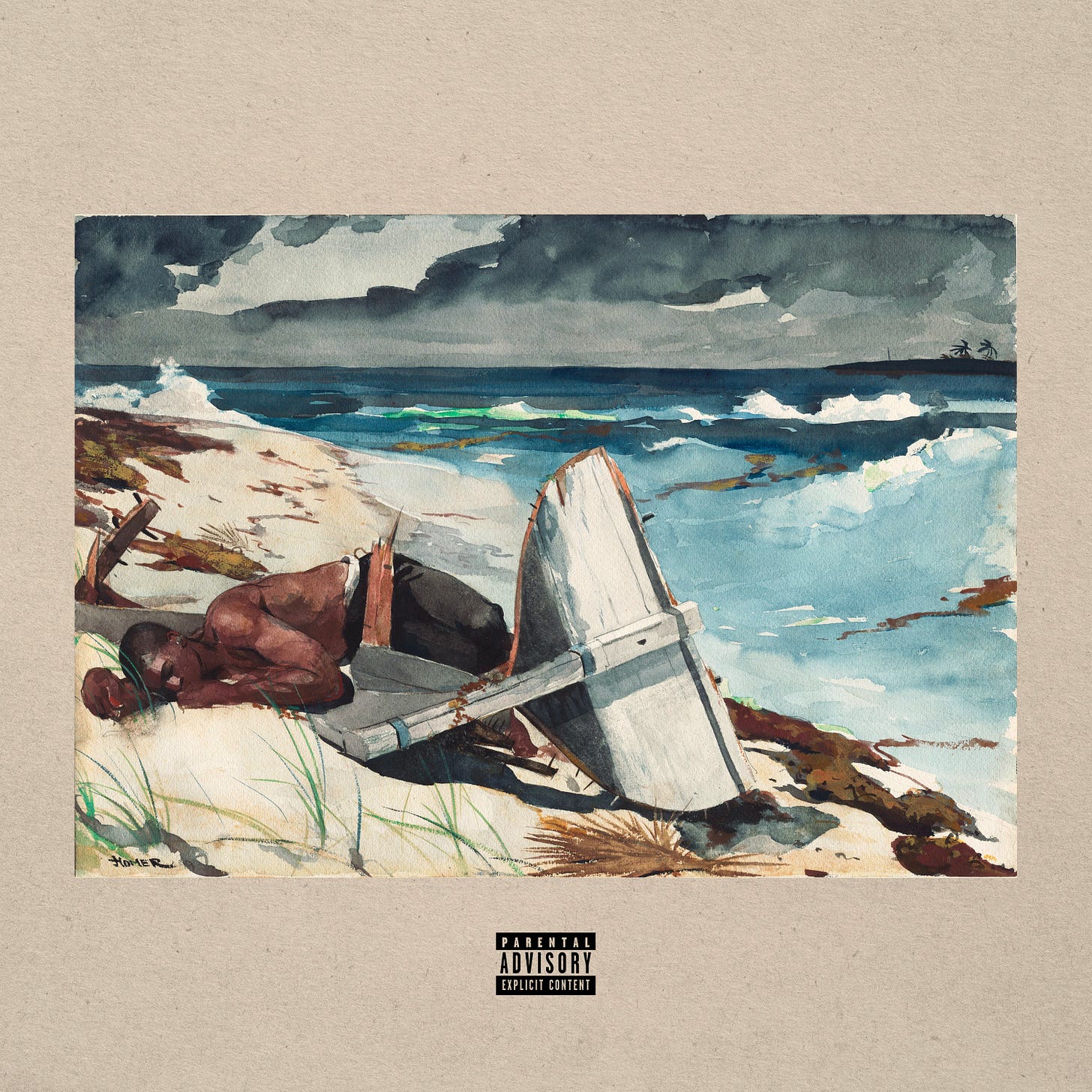

Dave, The Boy Who Played the Harp

Dave cut his name out of the blocks of South London, Brixton blocks, with the one-take treatments, healing therapy sessions with Psychodrama in 2019, that revealed the scars of knife crime. He followed with the epics of family with We’re All Alone In This Together that put him three-and-a-half-meters taller than his contemporaries in UK rap, and The Boy Who Played the Harp that put his scars of heritage on the harp strings that turned scars into folk heroics of heritage and loss. “History” unravels generational threads with “Yeah, I sometimes wonder, ‘What would I do in a next generation?’/In 1940, if I was enlisted to fight for the nation,” verses tracing ancestral echoes from war drafts to modern drifts, James Blake’s keys heighten how pasts pluck at presents unbidden. “175 Months” confesses timelines to the divine, “Lord, it’s been 175 months since I last felt whole,” a raw reckoning of years stacked like debts, his flow pleading for grace amid the grind that shaped his grip on the mic. “Selfish” owns ego’s edge, “I’m selfish with my time ‘cause time’s all I got,” verses weighing solitude’s cost against connection’s claims in a balance that tips toward guarded growth. He takes the lineage and turns it into a living song, melodies that play harps over chronicles, turning the bruises into the music of diligently enchanted here. — Phil

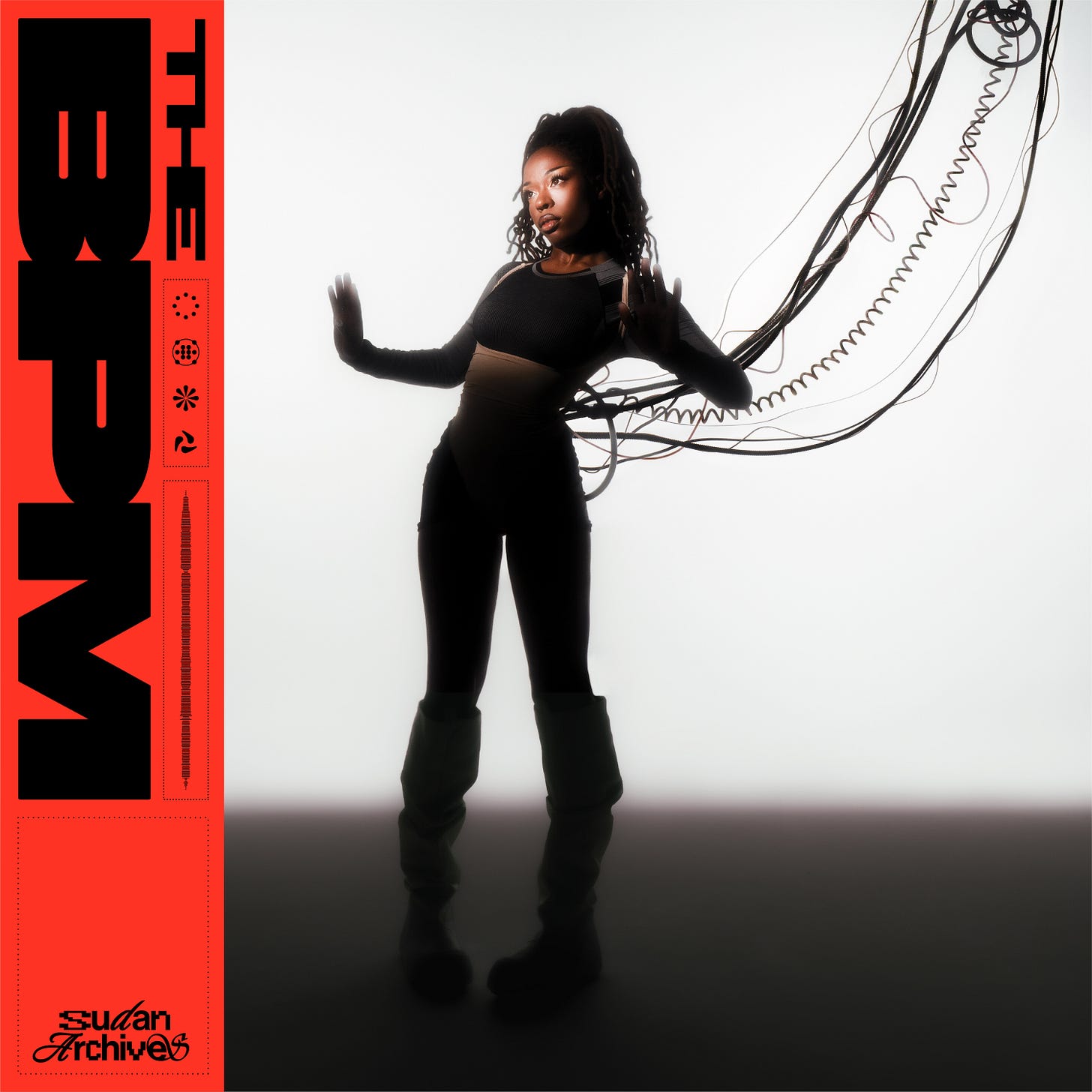

Sudan Archives, The BPM

Brittney Parks had been playing her violin in Cincinnati basements, learning on her own, and hauling it across the country to LA studios and then superimposing those strings both over beats that smoothed out the edges of R&B with hazy production and experimental loops creating an image as the violinist using folk origins to transform into future confessions, on early recordings such as her debut that spoke in whispers of vulnerability. Back from a 2022 sleeper, The BPM propels them on there into club-lit explorations of the desire with question marks swirling through it, her third full-length swinging both euphoric high and shadowed pull, forcing you to move, doubting every move. “Dead” begins with a verse that seeks answers to lost parts of self, “Tell me, can you tell me where my body goes? I don’t wanna step on anybody’s toes” her words going round the nervousness of not fitting in new skins, dividing the lines of light and dark in a call-and-response that is a push-pull of intimacy, repeating “Hello, it, me/Did you miss me?/Just take this piece/The best of me,” as an uncertain gesture to one who could break it all so hard again. “Touch Me” pushes into that skin-hunger, beginning with shiver at its most basic form, a scat on the skin, “Touch me/It gives me chills, my waist, all on my body,” rejecting the overconsumption of how to deal with parties in favor of the sensation of authentic connection, the second verse in the song acknowledging the eny of a competitor in possessing her curves as an heir, the text removes fences to literally show how touch brings the messiness in. “A Bug’s Life” downsizes the size of heartbreak inspirations to insect-sized ludicrousness, lyrics fulfilled with cynical commentary on temporary relationships that leave you crawling around in search of something substantial, and the performance of Parks makes laughter in the face of frustration a shrug of the shoulders set to the beat that takes the sting out without ignoring the song. — Jill Wannasa

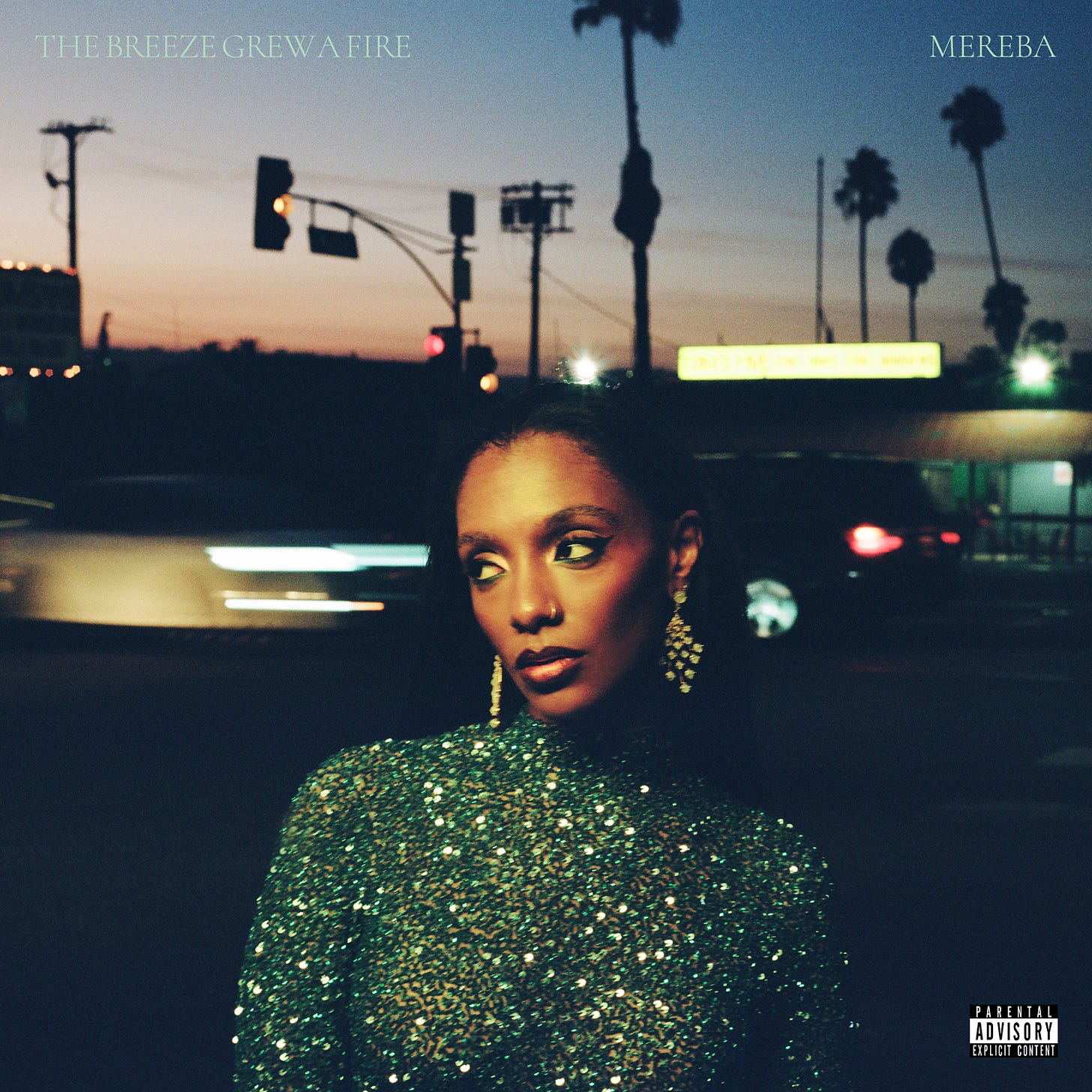

Mereba, The Breeze Grew a Fire

The work of Mereba has always felt like a search for equilibrium, but motherhood and a forced pause during the pandemic pushed her to write about stability itself rather than the ups and downs. In recent interviews, she said she became fascinated by how “a gentle loving relationship can make a very powerful person.” That idea gives the album its title. Songs here celebrate bonds that aren’t flashy yet change everything. On “Heart of a Child,” she daydreams about younger years and asks a partner to reclaim an innocence they’ve lost together, singing that it’s been a while since they’ve “had the heart of a child” and promising to travel miles until they do. Elsewhere, Mereba uses Ethiopian instruments like the masinko and krar as subtle nods to her heritage, mixing them into meditations on friendship, family, and spirituality. The project gravitates toward small gestures that ignite inner fires—the feeling of a breeze on a hot day, a son’s presence reminding her to trust instincts, or a late‑night conversation that rekindles hope. By the time she revisits her inner child in the track named after it, she isn’t looking for novelty but for a grounding she can pass on, proof that tenderness can carry as much weight as upheaval. — Brandon O’Sullivan

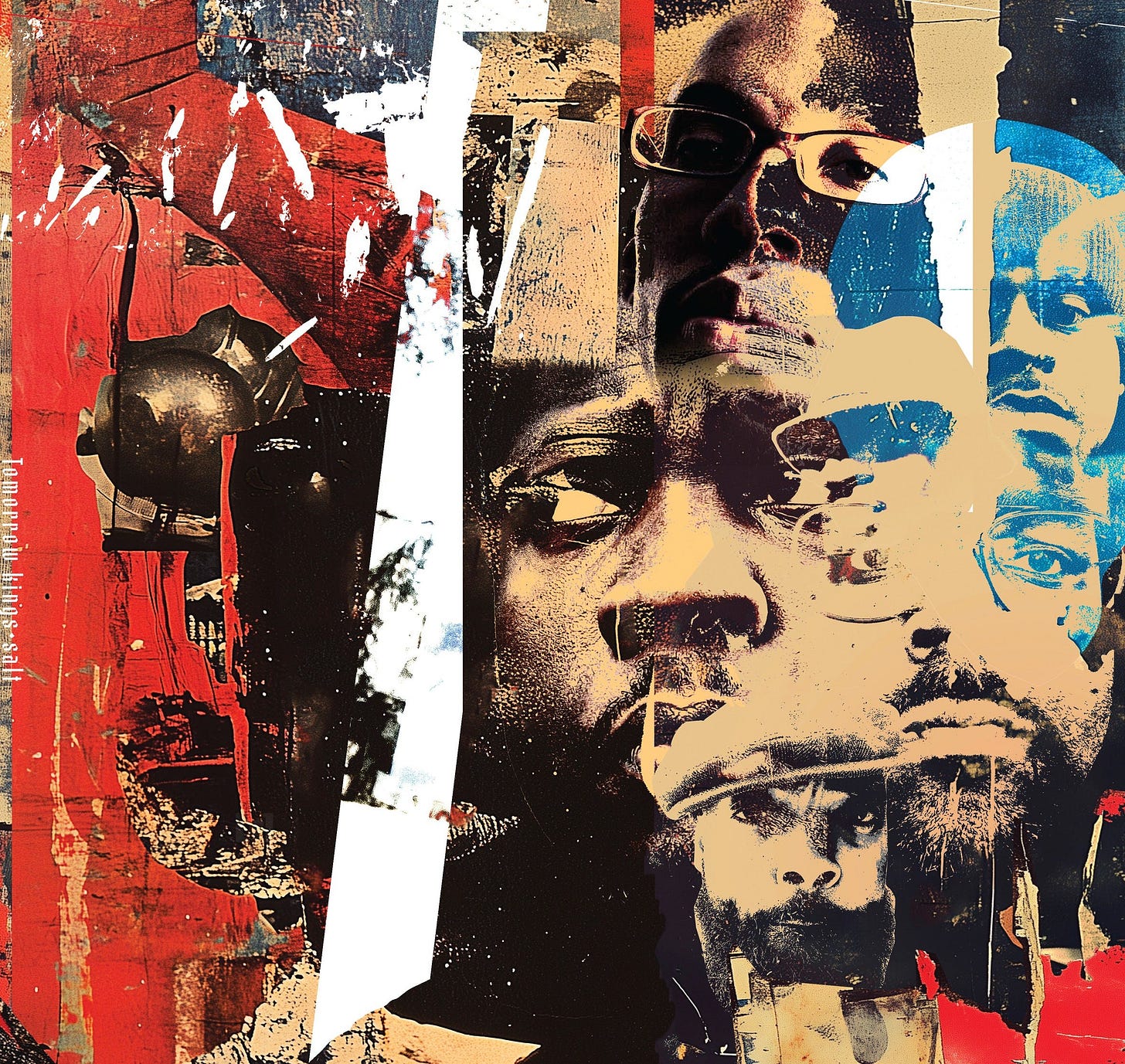

De La Soul, Cabin in the Sky

They were visionary and taboo-breaking on several occasions. Despite the sunny nature of their music, released since 1988, the jazz-rap pioneers De La Soul already addressed the story of a girl sexually abused by her father on their second album. Artificial intelligence became a central theme for the trio in their AOIseries, which coincided with the turn of the millennium and, soon after, the horrific events of 9/11, in De La’s hometown of New York. They steadfastly distanced themselves from the gangster rap that was flooding their scene at the time. The world always listened to them, far beyond genre boundaries, for example, when they opened for The Flaming Lips or collaborated with the Gorillaz. Their return with Cabin in the Sky was unexpected. But Trugoy, one of the three MCs, didn’t live to see it. The album’s diverse range of expressive modes includes children’s and monster voices, gurgling scratches on the voice, a radio play with screeching and slamming doors, announcements for a breathing exercise, elegant choral singing, and even an introductory round at the beginning. It is a warm, sunny, and emotional work, as can already be seen in song titles such as “Sunny Storms,” “Cruel Summers Bring Fire Life,” and “Day in the Sun (Gettin’ Wit U).” Besides the breadth of themes and vocal delivery, the sound design is also multifaceted, thanks to Pete Rock, DJ Premier, Nottz, Jake One, and others. With the help of a stacked feature list of the year, including everyday philosophical musings, De La Soul goes a big step further and builds upon the historically significant works of their early years. — Brandon O’Sullivan

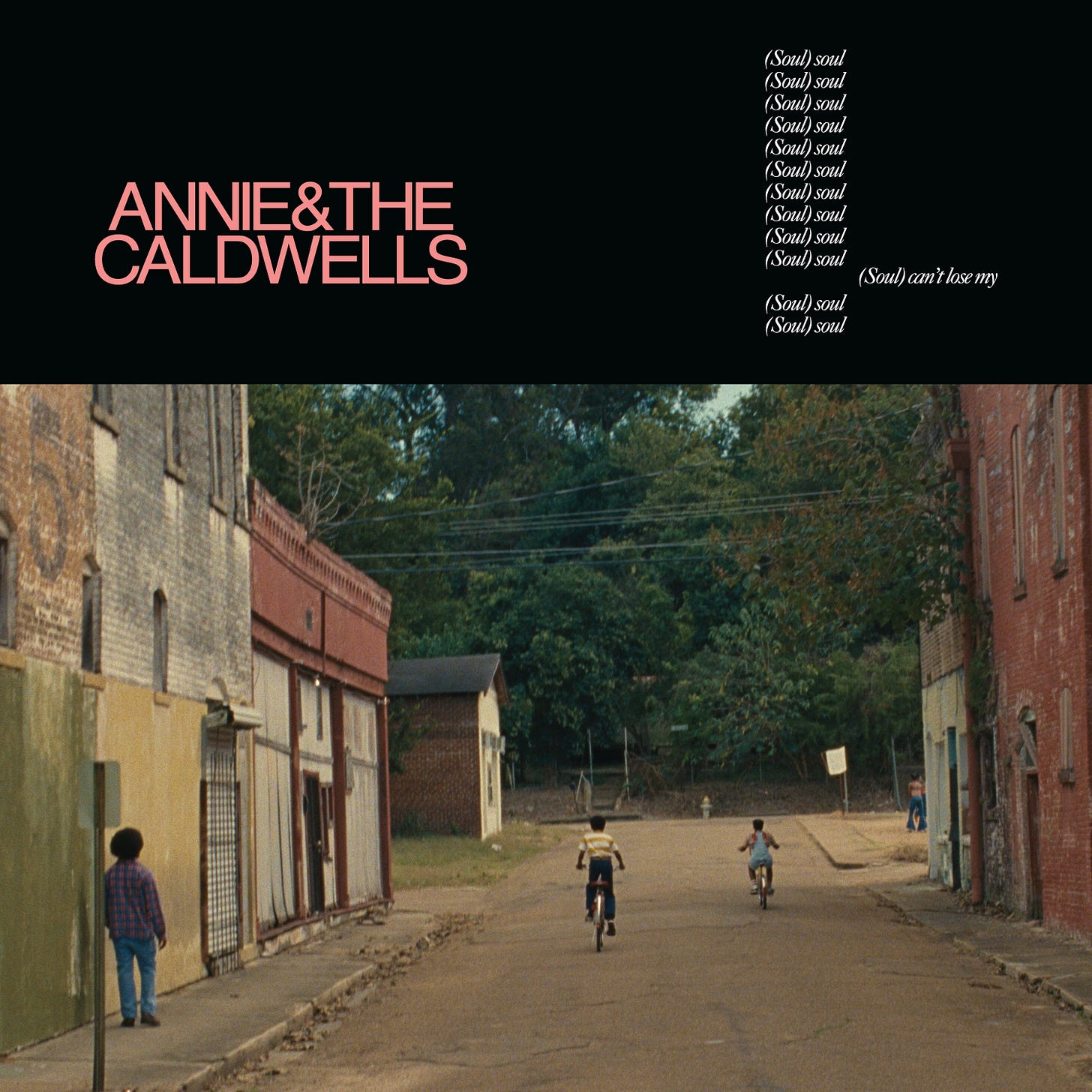

Annie & The Caldwells, Can’t Lose My (Soul)

The story behind Can’t Lose My (Soul) is almost as compelling as the record itself. In the early 1970s, Annie Caldwell and her siblings released a single as the Staples Jr Singers. Decades later, crate‑diggers resurrected that 45 and sparked a revival, leading to a modern recording by Annie with her daughters that sounds like a family band reclaiming its own history. The title track stretches ten minutes, pulling you through the murk of soul, not some organ you can pin down, but the root of the genre’s name. Sinkane builds it tight and fills it with layers of soundtracks propping each other up, with every voice fighting for the front. It’s no timid gospel redo. That spirit carries into “Don’t You Hear Me Calling,” where call‑and‑response vocals enact the urgency of prayer, and “Dear Lord,” whose liquid bassline and funk groove offer a plea for guidance without succumbing to despair. On “I’m Going to Rise,” the group draws on southern soul, promising to get up and keep going despite grief, while disco‑tinted numbers such as “I Made It” and “Wrong” recall Chaka Khan and celebrate survival. The album hits like a first swing, rethinking 2025’s take on the sacred with a gut-punch drama. Byrne’s eye for quality holds—audio nuts will geek out, but the weight sticks. Experience shows, and the struggle is now paying off. — Imani Raven

Oklou, Choke Enough

Marylou Mayniel spent years in the Parisian post-club underground, refining electronic atmospheres for artists like Sega Bodega and remixing PinkPantheress before anyone knew who she was. Her debut as Oklou arrives three years after the introspective Galore EP positioned her as someone capable of wringing genuine ache from digital sound. Choke Enough proves she’s figured out how to make minimalism feel extravagant without adding more. Mayniel’s voice floats through these songs like breath on glass, never quite touching down. “Family and Friends” builds from hardly anything into a chorus that stacks her vocals into a choir singing to no one in particular, while “ICT” plays with video game chirps and Auto-Tune that bends notes into question marks. The Bladee feature on “Take Me By the Hand” feels inevitable, two artists who understand how to make loneliness sound like a color. When underscores appear in “Harvest Sky,” they add texture to what’s already there rather than interrupt it. After all, you’ve either accepted that Oklou operates in negative space or you haven’t. This is music that asks you to lean in rather than shouting across the room. — Charlotte Rochel

Terrace Martin & Kenyon Dixon, Come As You Are

Within a framework of supple Rhodes chords and barely there drum loops, Terrace Martin and Kenyon Dixon explore self-regard as a communal practice. Dixon speaks plainly about love and vulnerability, offering insight into emotional surrender. Martin complements that with understated yet expressive jazz touches—Robert Glasper and Keyon Harrold add soft flourishes that nod to LA’s rich musical heritage. Rather than spell out gospel influences, the pair fold call-and-response backing lines into slow-bloom arrangements that feel lived-in. Martin keeps his horn cameos sparse so Dixon’s tenor can press forward with plain-spoken reminders to “love yourself” and “keep your circle tight.” Those phrases may read simple on paper, yet the singers treat them as working lessons, revisiting them over subtly shifting keys. When Rapsody drops into “WeMaj,” her measured verse about trusted friendships widens the album’s moral compass without breaking its hush. Keyboards and bass stay in dialogue, moving just enough to suggest forward motion while leaving space for breath. Together, they prove modern R&B can speak softly and still cut deep when craft serves purpose rather than ego. — Phil

Isaia Huron, Concubania

Raised in a South Carolina church and sharpened as a drummer, Isaia Huron moved to Nashville to build as a writer and producer. In the wake of a run of EPs and a loosies tape that hinted at range without settling the stakes, he makes a first full statement with a debut album that’s way more than just ‘solid.’ In recent interviews, he’s tied the idea to the mess of desire and faith, drawing a clear line between biblical cautionary tales and the way people move now, which gives the album a moral center without turning it into a sermon. That path explains the way Concubania is, where his writing stops auditioning and starts holding itself to account. On “I Chose You,” he writes from inside commitment rather than around it, describing the pull of impulse and the stubborn work of staying, and the verse-to-verse shifts feel like someone arguing with his habits in real time. “See Right Through Me,” a duet with Kehlani, pushes that tension further by turning confession into a two-way test of trust, as the exchanges read like carefully worded texts finally said out loud, and the pockets of silence between lines make the promises carry weight. He studies the language of uncertainty head-on—“I Think So?” and “Unsure” give indecision shape, not by hedging but by naming what doubt actually sounds like when you’re trying to choose better. “List Crawler” is a story song about curiosity and surveillance, brisk and specific enough to feel pulled from a real thread you wish you hadn’t scrolled, while “Thotful” turns defensiveness into a small character sketch. Across the set, Huron’s voice stays conversational and direct. He builds a record you can follow like a candid journal, where the details do the heavy lifting. — Harry Brown

Lady Wray, Cover Girl

Lady Wray has since built a catalogue steeped in church harmonies and old‑school rhythm‑and‑blues. Cover Girl finds her easing into that role with confidence. After the introspective Piece of Me, this record is more playful and uplifting, blending 60s soul, 70s disco, 90s hip-hop, and gospel influences into one celebratory mix. The organ‑driven “My Best Step” uses hand‑claps and church keys to reaffirm loyalty and perseverance, and the album’s messages of empowerment are apparent in songs such as “Where Could I Be” and “Hard Times,” which invoke faith and resolve amid hardship. The title track revisits a childhood nickname as Wray sings about losing herself to please others and the slow process of rediscovering her own beauty. Throughout the album, she reminds women that they are worth more than society tells them, as on the retro‑soul groove “Higher,” and she ends with “Calm,” a gospel‑tinged prayer that casts burdens aside and looks toward brighter days. Lady Wray delivers an album that balances upbeat anthems with honest reflections on love and self-acceptance, drawing from her church roots and decades of experience. — Imani Raven

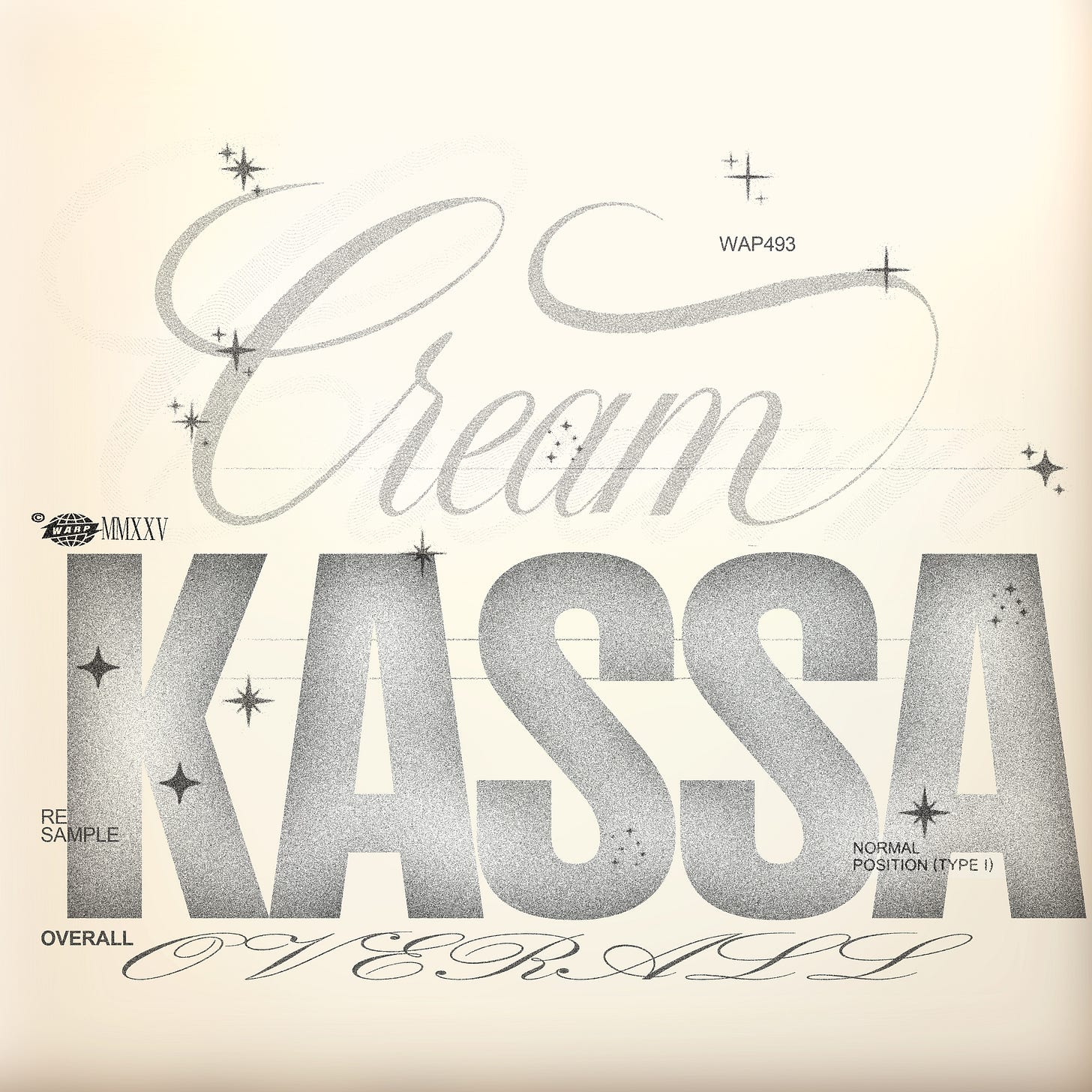

Kassa Overall, CREAM

Kassa Overall has always heard jazz and rap as parts of the same nervous system. He switches between trap‑leaning drums and swing patterns without asking permission, so a set of versions of ‘90s hip‑hop songs feels less like a detour and more like him laying his cards on the table. Sure enough, he delivers. On CREAM, he takes tracks everybody knows by muscle memory—“Big Poppa,” “C.R.E.A.M.,” “Nuthin But a ‘G’ Thang,” “Rebirth of Slick,” “Back That Azz Up,” “SpottieOttieDopaliscious”—and pulls them apart until only the contour of the hook and the feel of the original beat are left, then rebuilds around live drums, keys, and horns. Sometimes he leans close to the source, letting the bassline or chord movement sit almost unchanged while the band plays with time and texture around it; other times he handles the tune like a sample that never existed, starting from a small rhythmic idea and letting fragments of the original vocal cadence appear in the way the instruments phrase. Because he’s rapping, drumming, and producing, he can shift point of view mid‑track: one moment you’re inside a drummer’s head, counting subdivisions, and the next you’re hearing how a teenager in love with these records might have freestyled over them in a bedroom. It ends up sounding less like a “jazz covers hip‑hop” gimmick and more like a working drummer showing how those records rewired his sense of swing and harmony in the first place. — Phil

Cleo Reed, Cuntry

Cleo Reed filled the Brooklyn Museum atrium with shadow-puppet projections while premiering songs from the self-released Root Cause EP, looping banjo plucks and Ableton-warped sirens until passers-by mistook the lobby for a picket line. Countless van voice notes, and a season of wildfire haze later, the multidisciplinary artist delivers Cuntry, driven by a need to catalogue survival tactics forged at the intersections of queerness, Blackness, and labor precarity. Reed self-produces but invites Matthew Jamal’s bowed double-bass, Isa Reyes’ processed field recordings, and billy woods’ gravelly poetry to craft an electronic-folk hybrid where foot-stomp percussion collides with glitching modular patches. Nick Hakim whispers falsetto on “Get a Grip,” Elliott Skinner’s choral stack lifts “Women at War,” and Annahstasia drapes “Americana” in reverb-soaked twang, tracing a sonic road trip from borough stoops to desert highways. Cuntryspotlights lineage, from hip-hop raconteur to soul stylist to folksinger—echoing the record’s thesis that no movement advances on a single genre’s shoulders. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Bad Bunny, Debí Tirar Más Fotos

Released a day before Three Kings Day, Bad Bunny puts his heart on his sleeve for Puerto Rico in ways that go beyond simple nostalgia or celebration. The title translates to “I Should Have Taken More Photos,” and every element of the rollout emphasized the album as a gift to the island and its diaspora, from coordinates scattered across Puerto Rico via Google Maps and Spotify to visualizers displaying Puerto Rican history compiled by professor Jorell Meléndez Badillo. The music pulls from plena, jíbara, bomba, and salsa alongside reggaeton and dembow, creating a patchwork of the island’s sounds rather than a single vision. “NUEVAYoL” samples salsa track “Un Verano en Nueva York” and builds it into something forceful, while “CAFé CON RON” works with Los Pleneros de La Cresta to layer Afro-Puerto Rican musical styles over electronic beats. “BAILE INolVIDABLE” pays direct homage to Willie Colón and Héctor Lavoe’s Fania recordings, pulling from “Juanito Alimaña” and “Periódico de Ayer” without simply copying them. The writing moves between political commentary and personal loss, sometimes in the same song. — Charlotte Rochel

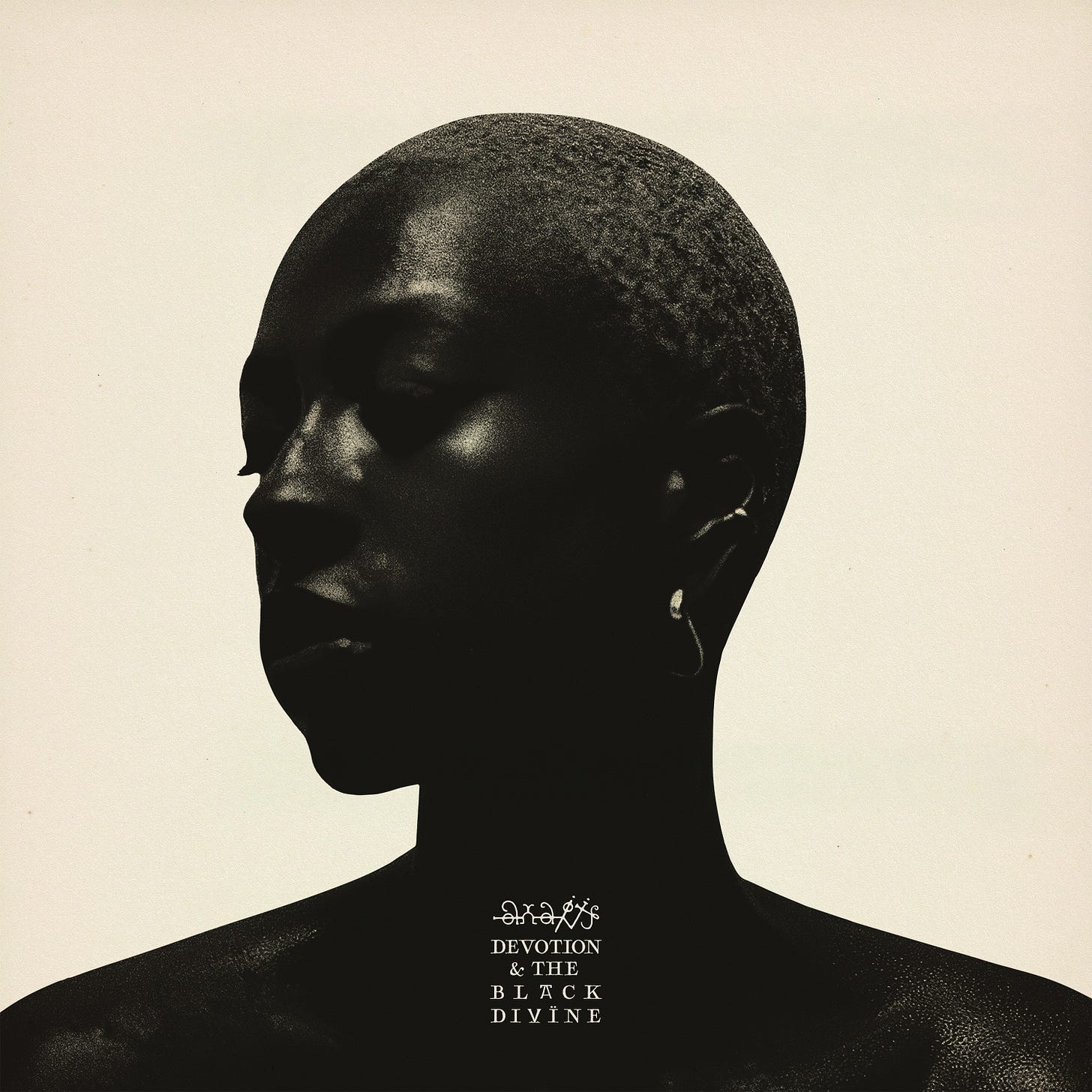

anaiis, Devotion & the Black Divine

anaiis writes from what she calls a collective consciousness, letting the album serve as a conversation between herself and the world. Recorded live to tape at London’s 5dB Studios, Devotion & the Black Divine grew out of her experiences as a new mother and her search for acceptance. The songs lean into uncertainty and grace, capturing the messiness of being human while holding on to a still center. On “Moonlight,” she sings gently over swirling chords, contemplating how hope can persist in darkness. The slow, sensual single “Deus Deus” heralded the record with its sultry soul reggae groove, hinting at the album’s spiritual core; its repeated gratitude expresses a personal prayer without ever becoming didactic. She moves between spoken‑word cadences and melismatic runs, reflecting on the weight of motherhood and the freedom that comes from surrendering control. Although the arrangements shift from sparse ballads to experimental R&B, the through‑line is her willingness to place every emotion at the core. — Ameenah Laquita

Yaya Bey, Do It Afraid

Yaya Bey opens with a mantra of courage: “If you want to be brave, first you gotta be afraid,” and she lives by it across pastoral instrumentals that mix acid jazz, trip-hop, reggae, and soca. She moves between intimate confessions and buoyant grooves. The Caribbean pulse of “Merlot and Grigio,” featuring her Barbadian collaborator, showcases her ease in marrying American soul with diasporic pulses. She addresses emotional labor and misogynoir with upfront candor while never sacrificing the warmth of her voice. The arc is of trudging through fear toward clarity and self-acceptance. She skips between swagger and reflection but keeps it all grounded in a patient groove. Instead of chasing a glossy hook, she leans into conversational cadences that turn everyday grievance into melody. On “End of the World,” muted horns from Butcher Brown bloom behind her voice, framing apocalypse talk as block-party small talk. Elsewhere, “Real Yearners Unite” pares instrumentation to finger snaps, allowing the singer to confess that craving tenderness can feel defiant. By keeping production minimal and language direct, she turns personal risk into a shareable blueprint for survival. — Jamila W.

Kojey Radical, Don’t Look Down

Having made a splash with Reason to Smile, Kojey Radical now takes more inward turns; this follow-up is less about gloss, more about fissures. He began with reflections: spoken-word prologues, reckoning with grief (“How many homies didn’t make it?”), parenthood, identity, public image. He’s still the poet-rapper, but here the narration is more continuous, more panoramic. If you’re a fan of Radical, you know he leans into sample-rich textures, jazz inflections, symphonic soul touches—songs aren’t just beats plus verse but atmospheres you step into. There aren’t obvious radio hits, but each track feels necessary, revealing parts of the emotional scaffold, with pressure, doubt, and the longing for honesty. This breadth is evident in the music (featuring Ghetts, Bawo, MNEK, Dende, and James Vickery), which draws on golden-age hip-hop, disco, grime, indie, jazz, and ska to create a shifting sonic landscape. In interviews, he explains that he wants to be transparent about his flaws so fans can trust him, as he struggles with pride, pressure, ambition, and exhaustion. Within UK rap/progressive hip-hop, Don’t Look Down stakes a claim for patience: for letting songs marinate; for letting any music fan slow down and sit with discomfort. It’s one of those albums that rewards absorption, repeated plays, and is perhaps one of his strongest works yet. — Randy

Theo Croker, Dream Manifest

Theo Croker pulls themes from a dream journal, translating them into nine concise instrumentals and vocal collaborations. “Prelude 3” pairs piano with muted trumpet, establishing a relaxed conversation before fuller grooves appear. Estelle and Kassa Overall share gentle lines on “One Pillow,” set against brushed snare and soft bass that keep the mood close. “64 Joints” runs longer, allowing Tyreek McDole to float over slow keys while the rhythm section holds steady. “Up Frequency (Higher)” edges pace upward, yet air remains in the mix for horn flourishes. Gary Bartz joins “Light as a Feather,” trading concise phrases with Croker that favor dialogue over display. MAAD and Malaya add subtle R&B shades on “High Vibrations,” widening the palette without crowding instruments. Croker prefers analog warmth, evident in rounded horn edges and lightly saturated keys. Throughout, Croker prioritizes emotional clarity and collective balance over technical parade, inviting listeners into a quietly imaginative sound world. — Nehemiah

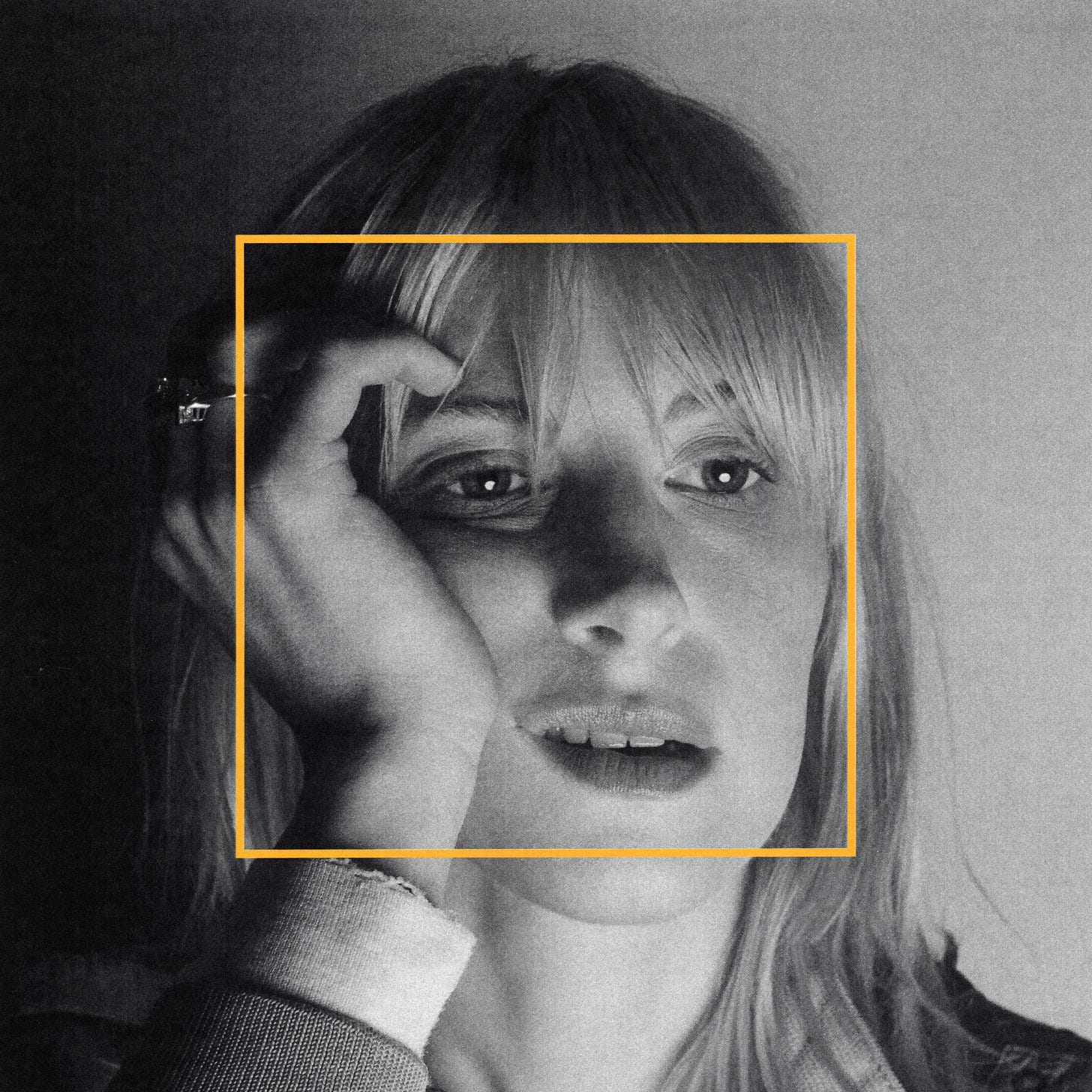

Hayley Williams, Ego Death at a Bachelorette Party

After years of fronting Paramore and two solo sets that traced emotional freefall and rebuilding, Hayley Williams suddenly dumped seventeen songs on her site and then platforms, a hard nucleus back to direct address where the writing toggles between self-audit and wry provocation, the songs feeling like dispatches she didn’t want sanded down by rollout. The draw here is specificity—on “Mirtazapine,” she names the medication. She writes to it without coyness, even admitting “You make me eat, you make me sleep,” the melody moving like a steady hand on the shoulder. At the same time, the verses catalog the symptoms and relief, and “Negative Self Talk” lives up to its title by turning the phrase into a chant that crowds the room, line after line testing the volume of that voice until the chorus feels like a boundary finally set. “Discovery Channel” flips a notorious hook—“You and me, baby, ain’t nothing but mammals”—and the lift becomes a joke with teeth, a way to talk about desire and agency without dressing it up, while “Mirtazapine” and “Glum” linger on private weather without hero pose, her phrasing clipped when the thought hurts and open when the air returns, the production staying out of the way so the writing can do the heavy lifting, which it does, repeatedly, in songs that read like marginalia from someone learning to narrate their own mind in real time. — Charlotte Rochel

Blood Orange, Essex Honey

Dev Hynes composed the majority of Essex Honey while in mourning at his family home, helping it materialize as an intricate palimpsest of memory and grief. He navigates oscillations between domestic stasis and psychological fragmentation, voicing lines and the exhausted avowal: “I don’t want to live here anymore.” On “Mind Loaded,” he reiterates a refrain that enacts both psychic burden and corporeal ache: “Still broken, can’t think straight, mind loaded, heart still aches … ‘Musil’ in my brain.” Joined by Lorde and Mustafa, he articulates an existential insight—“Everything means nothing to me/And it all falls before you reach me”—emphasizing how grief corrodes signification even amid collective gestures of care. “Vivid Light” stages a juxtaposition of flute and piano against a hip‑hop rhythmic frame, while “The Last of England” embeds a recording from his final Christmas with his mother before devolving into trip‑hop. The work shifts fluidly among sites of mourning within the domestic sphere, creative inertia within rented studio confines, and contemplative excursions into the countryside. Collaborators such as Lorde and Caroline Polachek assume equal prominence, forming a polyvocal environment through which Hynes negotiates bereavement. Essex Honey resists simplistic catharsis. Instead, it dwells within the liminal interstice between lament and tentative solace, allowing fragile motifs and elliptical lyric fragments to communicate the gravity of grief without recourse to dramatization. — Phil

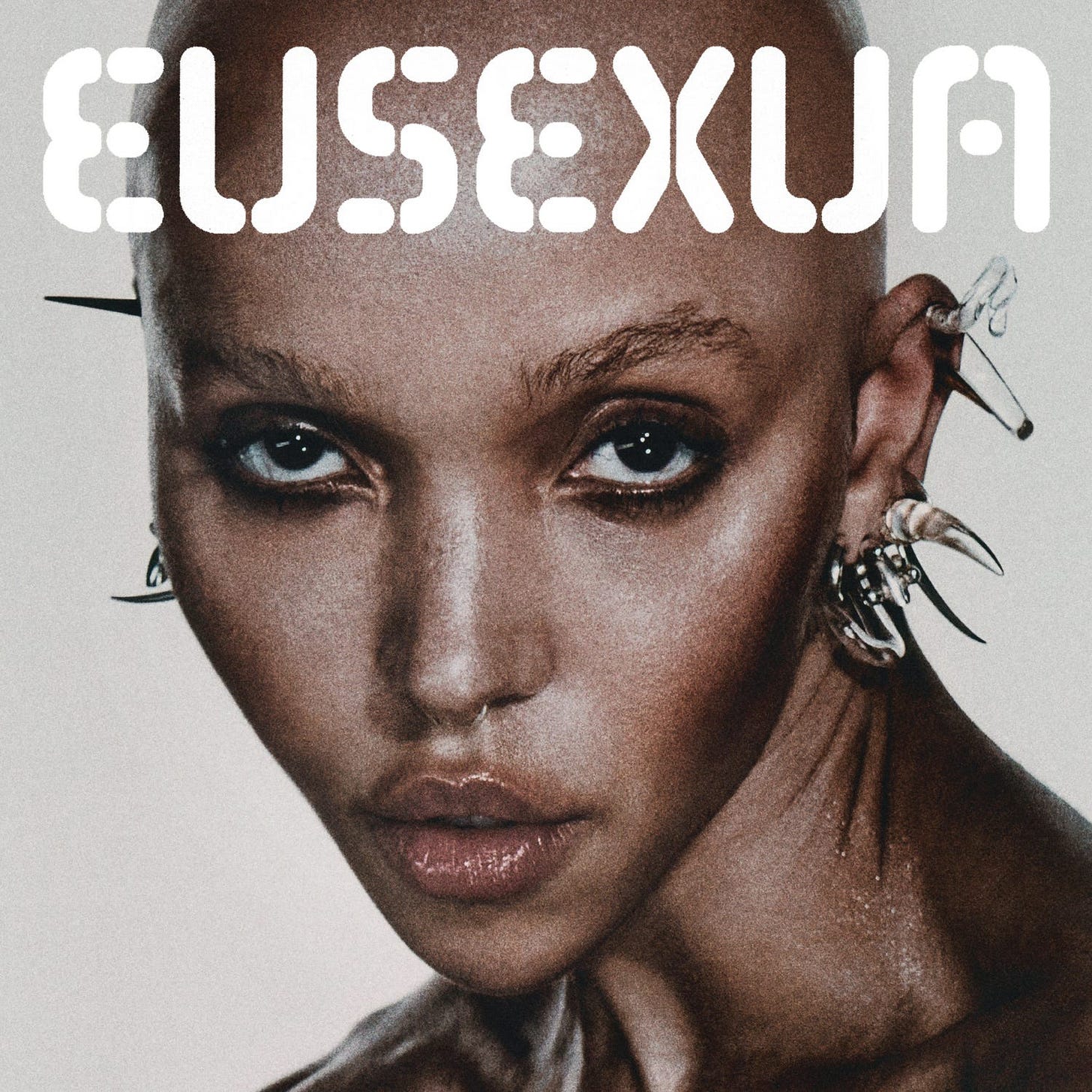

FKA twigs, Eusexua

Years between Magdalene and this, her third album, though the 2022 mixtape Caprisongs suggested FKA twigs hadn’t been sitting still. She relocated to Prague a couple of summers back and fell for techno while working on The Crow soundtrack, not the genre itself exactly, but its spirit, the warehouse raves where ego dissolves, and bodies move without thinking. Eusexua is her invented word for the nothingness and focus someone feels approaching orgasm, which is a pursuit of transcendence through sound and sweat. The title song opens the album with three and a half minutes of strobing tension, twigs’ voice processed into something cybernetic, half-human and half-machine, singing about crashing systems and serving violence over Koreless production that feels both thrumming and delicate. Koreless worked on every track here, his fingerprints all over the throb and pulse that drives these songs. “Perfect Stranger” and “Drums of Death” were released as singles ahead of the album, establishing that twigs wasn’t making electronic music that sits politely in headphones—this is music built for rooms full of bodies, for hot flesh against cold metal. “Girl Feels Good” turns into subterranean trip-hop with dubby piano, while “Room of Fools” brings big-room melodrama with strobing lights implied in every synth hit. She’s singing about strangers emerging from fog, everyone seeking sticky, sweaty catharsis that kills the ego. — Charlotte Rochel

Chronixx, Exile

It has been eight years since Chronixx released a full-length album, since his debut set the pace for modern roots reggae. The joining of SAULT and the collaboration of Inflo make Exile one of the strongest statements in the genre in years. The album is a mixture of traditional roots harmony and warm soul, mixed with experimental boundaries. One cannot say that his only strength is in his hooks or his lyrics; it is a matter of putting them into practice with the help of a voice that is full of enthusiasm and innate star qualities. His self-confidence is nonchalant. Chronixx ponders on inflation (“Market”), his community in Jamaica (“Family First”), and hypocrisy within the political space (“Saviour”). His voice is constant and soulful, and Inflo production is a richness and a range lacking in much of the modern reggae. — Ameenah Laquita

Sumac & Moor Mother, The Film

Conceived as an “imaginary documentary” score, this 50-minute behemoth fuses Sumac’s free-form post-metal with Moor Mother’s oracular spoken-word. Recorded live in single takes, movements flow like reel changes: “Scene 2: The Run” lurches from hi-hat shrapnel into sludge-bass avalanches, while opener “Camera” finds Moor Mother chanting “I want my breath back” against detuned drones, a visceral nod to present-day suffocation—literal and political. The closer, a 16-minute tidal wave of feedback and free-jazz cymbal wash, leaves her whispering “memories from planet Earth,” as if panning over post-apocalyptic credits. Rather than riff-plus-vocal stacking, the collaboration melts both vocabularies into what reviewers are calling free-metal: structure-less yet composed, spiritual yet furious. — Nehemiah

Durand Jones & The Indications, Flowers

From late-night Chicago writing sessions, Durand Jones & The Indications return with a body of work that treats grown-up intimacy as dance-floor fuel. The brief intro “Flowers” leads into “Paradise,” where Aaron Frazer’s falsetto glides over an easy bass line reminiscent of early-‘80s quiet-storm staples. Durand’s fuller tone on “Really Wanna Be With You” provides contrast, turning lyrical pleading into confident assertion. Strings lift the chorus without tipping into nostalgia, signalling the group’s intent to honor predecessors while sidestepping retro cosplay. Shared vocals dominate, a choice that underscores the album’s emphasis on collective resilience rather than individual virtuosity. Many takes were captured live, preserving tiny imperfections that make the grooves human enough to invite repeated spins. “Been So Long” articulates reunion joy with the line “it’s good to be back together,” summing the album’s narrative in everyday language. By balancing disco shimmer with straight-talk sentiment, the band proves maturity and fun can still share the same dance floor. — Imani Raven

Mourning [A] BLKstar, Flowers for the Living

The Cleveland collective—known for welding gospel harmonies, distorted bass, and free‑form poetry—uses this album around the idea of giving loved ones their flowers while they can still smell them. As Mourning [A] BLKstar blurred the line between lament and celebration, “Stop Lion 2” fuses distorted bass drone with a field-recorded Baptist shout, interrupted by a spoken-word salvo from Lee Bains that sounds like Gil Scott-Heron channeled through a post-punk megaphone, and you have the title track where vocalist RA sings about holding himself accountable while promising to motivate his community. Elsewhere, “Letter to a Nervous System” layers tape echo on dour trumpet lines, evoking the echo-chamber anxiety of the album’s title. Yet hope persists: closer “88 pt.” hinges on a modal, Major-7th guitar vamp that brightens each chorus, suggesting blossoms pushing through concrete. Multiple lead vocalists trade lines like communal testimony, transforming grief into collective propulsion. “Can We?” flips an older groove into a funkier plea, asking if the band can indeed be funky and letting the answer unfold through wry interplay. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Ledisi, For Dinah

Following salutes to Nina Simone in earlier parts of the decade, Ledisi now works with Dinah Washington, and a tight book of standards demonstrates how a great singer reads a lyric as lived fact and not museum text, and the style is a tribute to Washington without impersonation. “You Don’t Know What Love Is” inclines to disorientation and heartache, and leaves the questions unspecified long enough to hurt; then “You’ve Got What It Takes” answers with no less certainty or explanation than two people would in the morning than the myth does at night. In “Caravan,” the pictures are directed off into space, away towards traveling and eating stuff, and in “Let’s Do It,” the wordplay remains light and humorous with no winking or grimacing, and in “This Bitter Earth,” the sadness remains in silence, waiting till the bitterness turns into useful strength. She pins all that transformation through “What a Difference a Day Made” not as a flashback, but rather as a turn of events in the present, and writing revolves around the mere fact that one day can actually change a life. — LeMarcus

Brandon Woody, For the Love of It All

Woody’s trumpet tone sits somewhere between Clifford Brown’s caramel warmth and Christian Scott’s breathy edge, but his compositional sense is firmly of the present: trap-lilted hi-hats coexist with modal piano clusters and snatches of spoken-word prayer. The album is structured like a church service turned block party—opening fanfare, communal affirmation, ecstatic peak, contemplative benediction. Upendo, his long-running quartet, locks into polyrhythms that reflect Baltimore’s go-go legacy even as synth textures nod toward cosmic-jazz futurism. On “Never Gonna Run Away,” Woody quotes “Lift Every Voice and Sing” before vaulting into a double-time solo that feels like an asphalt sprint through North Avenue at dusk. He refuses the jazz-world trope of geographic migration, choosing instead to root the music in the city that raised him; the result is a record that radiates place-based love without turning parochial, achieving universality through hyper-local detail. — Phil

Yukimi, For You

Co-founded Little Dragon in Gothenburg in 1996 when she was still in high school, Yukimi Nagano met Erik Bodin, Fredrik Wallin, and Håkan Wirenstrand in rehearsal rooms where newly started bands gathered. Her voice became the band’s calling card—a fierce falsetto that announced major talent the moment anyone heard it. Little Dragon’s 2007 self-titled debut mixed electronica and indie rock with webby guitars and shiny synths, but it was Yukimi’s voice and words that compelled fans around the world. She’s since performed everywhere from Coachella to NPR’s Tiny Desk and collaborated with Mac Miller, Gorillaz, KAYTRANADA, and De La Soul. She opens with “Prelude For You,” spoken word explaining that when you write from a deeply personal place, it becomes human, that she’s calling this album For You because even though it’s about her, it’s equally about us, everyone spinning on the planet together. The album leans toward jazz and soul, moving away from Little Dragon’s electronic foundations toward a more organic, downtempo sound. “Make Me Whole” introduces the lush R&B production that carries through most of these songs, Yukimi’s voice floating over gentle arrangements. “Break Me Down” is the album’s most emphatic moment, a declaration of individuality and perseverance where her voice soars away from the verses about special moments with a newborn, singing about the day her child will spread wings and fly. At 40 minutes, it’s a portrait of the artist in her early forties, diving into personal history about motherhood, marriage, and mental health. — Tai Lawson

Blu & August Fanon, Forty

Instead of basking in nostalgia, Blu marks his fortieth year by curating a series of meditations with producer August Fanon. The Los Angeles rapper has spent nearly two decades narrating the everyday lives of his city, yet this project feels like a birthday card scribbled in quiet rooms. Over August Fanon’s warm, drum-less loops he reflects on fatherhood, friends lost, and the pressure of longevity. Mid-album, “Love (1-4)” runs nearly eight minutes, fluttering through four pocket-grooves while female vocalists stack harmonies like 1970s Roy Ayers sessions; the hook on “Big Picture” likens life to being stuck in a flash-photography row, and elsewhere he raps about the price of art and the distance between faith and fame. At forty, Blu doesn’t reinvent himself so much as take stock. The album’s pleasures lie in his everyday phrasing—quick notes about buying groceries, teaching his children patience, slipping into a memory of his grandmother’s house—delivered in a tone that suggests he’s rapping for himself first. Without relying on bloated listing, Blu and August Fanon craft a comfortable yet earnest album about growing older and choosing gratitude. — Harry Brown

Saba & No ID, From the Private Collection of Saba and No ID

Saba has spent his career threading vulnerability through lively Chicago storytelling, from the youthful optimism of Bucket List Project to the grief-stricken introspection of Care for Me. His latest project pairs him with veteran producer No ID, who mentored him through sessions that encouraged deeper self-examination. The songs, including the well-written “Big Picture,” he likens navigating fame to being stuck in a darkened theater, rapping, “I guess it’s like I’m in a show, sittin’ in a flash photography forbidden row,” a striking image of watching life unfold while the camera is turned off. Throughout the record, he meditates on the price of artistry and the emotional cost of staying present; one track frames painting as an apt metaphor for commitment, another chronicles the weight of expectations when your words are taken as gospel. Without relying on dramatic flourishes, Saba’s writing lays bare his anxieties and growth, leaving the collection as much a self-portrait as a collaboration. — Phil

Brandee Younger, Gadabout Season

Brandee Younger centers her harp on circular themes that invite a calm, reflective state of mind. Rashaan Carter’s bass and Allan Mednard’s drums supply light propulsion while keeping clear air around the strings. Recorded partly on a restored instrument once used by Alice Coltrane, the set honors lineage without leaning on nostalgia. “Reckoning” opens with a brief, searching figure that reappears in subtle variations later on. Shabaka’s flute on “End Means” slips in like a soft breeze, coloring the mix without turning the spotlight. “Breaking Point” toughens the groove with clipped accents while still leaving room for melodic breathing. Younger wrote every piece, and her intent shows in the disciplined pacing. She avoids flashy runs, aiming instead for motifs that bloom through repetition. Short overdubbed vocal sighs drift through “BBL,” hinting at R&B influence without a full stylistic pivot. Sessions took shape in her Harlem apartment, lending casual intimacy to the recording. By steering away from grand gestures, Younger underlines the harp’s conversational power on Gadabout Season that feels like time well spent in thoughtful company. — Brandon O’Sullivan

billy woods, Golliwog

When Golliwog opens with “Jumpscare” with warped horns and tape hiss, it sets a claustrophobic mood that never fully lifts. billy woods raps in dense, imagistic bursts, stacking references to colonial history, horror cinema, and everyday micro‑aggressions until the lines feel like overlapping newspaper clippings. Throughout the album, the production pivots between dusty jazz loops and abstract sound design. “Star87” floats over a detuned vibraphone riff that keeps slipping out of key, while “Misery” uses a brittle guitar figure that fractures under heavy reverb. Guest spots amplify the kaleidoscope; Bruiser Wolf’s off‑kilter drawl on “BLK Xmas” adds sardonic humor, Despot’s surgical precision on “Corinthians” sharpens the track’s edges, and ELUCID appears multiple times, his voice acting as both mirror and foil to woods’ weary baritone. The middle stretch (“Waterproof Mascara,” “Counterclockwise,” “Pitchforks & Halos”) digs into paranoia, with drums that drop out unexpectedly, forcing the listener to cling to woods’ internal rhythms for footing. Near the end, “Lead Paint Test” and “Dislocated” widen the sonic palette with industrial clangs and ghost‑choir samples, pushing the project into near‑apocalyptic territory. Despite the heavy subject matter, there is a sly playfulness in woods’ rhyme schemes; multisyllabic patterns tumble into sudden blunt phrases, mirroring the album’s thematic tension between performance and painful memory. — Phil

Ghais Guevara, Goyard Ibn Said

Structured in two acts, Guevara’s concept piece follows a fictional anti-hero who rises from corner rap star to luxury-brand demigod before watching the spoils curdle. Act I’s centerpiece “The Old Guard Is Dead” pairs roiling trap drum-programming with a compressed soul sample that sounds like vinyl spun backwards; Guevara rips through double-time boasts only to undercut them with “Aim for the moon, rose from the gallows”—a couplet that frames triumph as execution by another name. Act II flips the palette: “Leprosy” slows the tempo, substituting hazy guitar chops while he sneers, “actions don’t match their lyrics,” a self-indictment as much as industry critique. Throughout, his flows dart between Philly street punchlines and West African griot cadence, a nod to the historical Ibn Said, whose name he borrows. By finale “I Gazed Upon the Trap with Ambition,” the beats have thinned to skeletal clicks, and Guevara’s voice fractures into half-sung laments, the anti-hero finally staring into luxury’s hollow center. The narrative gambit never feels forced because Guevara’s technical fireworks—polysyllabic rhyme chains, sudden meter shifts—keep the story wired to the adrenal rush of outstanding rap records. — Brandon O’Sullivan

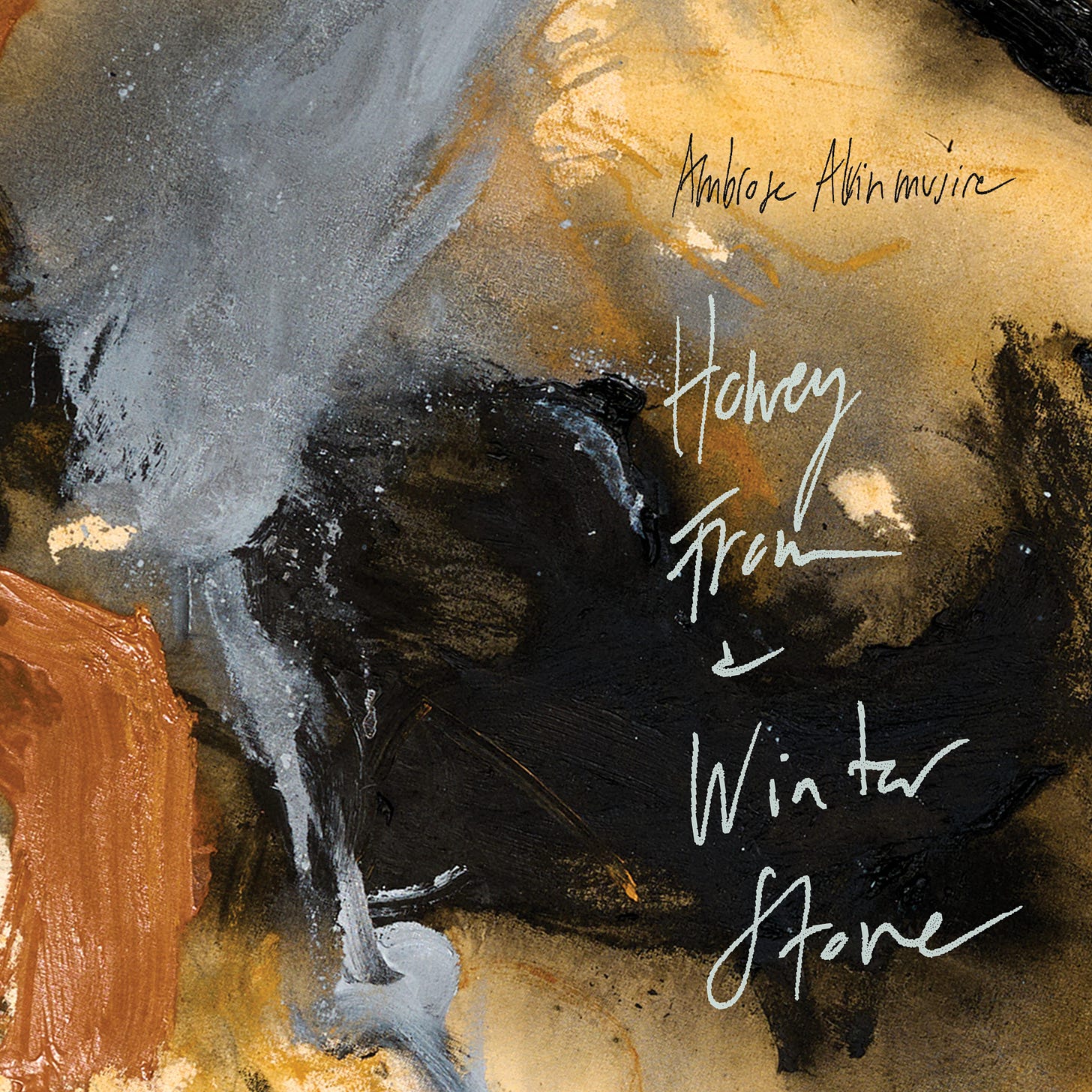

Ambrose Akinmusire, Honey from a Winter Stone

Sometimes, it starts with a place. For Ambrose Akinmusire, that place is Oakland, California: a city whose complexities—cultural, social, and sonic—have shaped not just who he is as a person but who he is as a musician. When Akinmusire released Origami Harvest in 2018, it was the clearest articulation yet of that wide musical embrace: a head-on collision of jazz improvisation, hip-hop verse, and modern classical strings. Now, with Honey from a Winter Stone, Akinmusire returns to that hybrid world with even greater confidence. He added vocalist Kokayi and synthesist Chiquitamagic to this already potent mix, creating a multi-genre tapestry where Mivos remains central and essential, not an afterthought. In these new pieces, Akinmusire grapples with issues he has named and claimed as personal: colorism, erasure, and the question of who has the right to speak for the Black community. It might look like jazz, hip-hop, and modern chamber music on paper, but, as with much of Akinmusire’s work, the reality exceeds any single category. — Nehemiah

keiyaA, Hooke’s Law

On her turbulent second album Hooke’s Law, keiyaA doesn’t just susurrate her frustrations—she unleashes them. The record confronts living in the gaze of the industry, the contradictions of self-care culture, and the weight of expectation as a Black queer woman (“an album about the journey of self-love, from an angle that isn’t all affirmations and capitalistic self-care… It’s more of a cycle, a spiral”). Adding her strengths as a well-rounded music producer, she welds jazz, club-music heat, and R&B tenderness into jagged, slippery grooves—Auto-Tune one moment, horn squalls the next—so heartbreak and anger sit beside seduction and swagger. What’s on the line is an album that doesn’t simply process pain, it confronts it head-on—and still moves you to dance. — Tai Lawson

Loyle Carner, Hopefully !

Loyle Carner turns away from community narratives and toward domestic life as a father, as his voice is low and conversational, sometimes even humming. He mixes rap and a previously unused croon with his singing voice, which emerges naturally and unforced. He speaks about the weight of being a parent, confessing doubt: “They said my son needs a father, not a rapper,” and “this fear in my belly” during early fatherhood moments. Where his Mercury-nominated Hugo wrestled with racial identity and paternal absence, Hopefully ! turns its attention to the immediate intimacies of fatherhood, partnership, and self-doubt. On the title track, he admits his faith in other people is aspirational: “You give me hope in humankind, but are humans kind?/I don’t know, but I hope so.” That ambivalence runs through the record. On “About Time,” he recounts an argument with his partner and confesses “another fucking thing I know you couldn’t forgive”; later, on “Lyin,” he describes himself as “just a man trained to kill, to love I never had the skill,” couching his fear of emotional ineptitude in the language of soldiering. Carner balances these heavy admissions with domestic snapshots: “All I Need” revisits his mother’s house, where the smell of “the sheets on my mother’s mattress” reminds him of learning backflips, and “Lyin” strings together surreal images of early parenthood, including a bedroom wall that falls “to Poseidon” and the feeling of a child’s hand tightening around his finger. Producer Avi Barath coaxes Carner into singing more than ever, and his low, unaffected croon cuts through the album’s sweetness like lemon juice. This feels like a journal of familial love and parental uncertainty delivered calmly but with care. — Murffey Zavier

Mobb Deep, Infinite

We lost Prodigy a long time ago, and the weight of that loss remains heavy. Havoc (along with Big Noyd) has been the one to keep everything in place, as they put together, yet the mention of Infinite restores all that made Mobb Deep untouchable. This year, more than any other, saw a revival of many pioneers in the hip-hop world as who joined hands with Mass Appeal for its Legend Has It series alongside Nas, Raekwon, Ghostface Killah, and a host of other artists. Whenever Prodigy speaks on a record, you can feel the burden of his art. A finely honed street philosophy, wordplay upgraded to lived experience, that stillness of purpose with which he could turn his empty words into poetry. The production of Havoc on Infinite is very precise, devoid of loudness and over-the-top bass sounds, very convenient bass notes, in the record “Pour Henny,” cool waves of the strings, drums beat your head, but does not declare itself aggressively, in the song, “We the Real Thing,” the bass sounds are very quiet, and the strings are the ones that shine through. It goes well with Alchemist, which adds light to grittiness, therefore keeping the attention on the bars. The album sounds like a time capsule and a tribute, a history of the fact that what Mobb Deep had created was not simply sound, but it was survival art. — Phil

Ayoni, ISOLA

Ayoni has always been the kind of artist who writes with the clarity of someone searching for her own reflection in real time. Building up her repertoire of loosies and featured on Noname’s Sundial, ISOLA is where that process transforms into a cohesive body of work. The title carries dual weight because it’s a nod to her Barbadian roots, an island identity that shapes her worldview, and it’s also an exploration of isolation, the way distance can magnify pain and foster transformation. She tells stories of heartbreak, anger, renewal, and self-discovery—songs that read like journal entries but are polished into resonant anthems. Tracks such as “It Is What It Is” and “Bitter in Love” walk directly into the grief of betrayal without posturing, while “Trace of Your Love” and “Vision” open the lens wider, asking what it means to hold on when love dissolves. She executive-produced the album herself, and that sense of authorship shows in the way motifs recur and melodies return as lessons. It’s a declaration of presence, proof that Ayoni’s pen and voice are strong enough to build universes without overstatement. It arrives as a debut that sounds like a marker planted in the ground, pointing toward even larger visions still to come. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Samm Henshaw, It Could Be Worse

Recorded with a live band and collaborators like executive producer Josh Grant and vocalist Ogi, It Could Be Worse runs through twelve tracks built on drums, piano, bass, and guitar instead of dense programming, leaving his gravelly tenor and stacked background parts space to crack, joke, and lean into faith without sanding the feeling down. Samm Henshaw is an artist who has one foot in church and one in a South London venue, raised on gospel records and mainstream pop, and trying to write songs that can hold gratitude, doubt, and everyday mess in the same breath. After his 2022 debut Untidy Soul and a mini‑album about burnout, he spent the last few years moving through family losses and his first major heartbreak, eventually landing on a phrase his mum kept repeating, “it could be worse,” as a way to file that whole period and as the title for a second album he’s described as the rawest he’s ever been. “Float,” the fourth song and one of the only tracks he’s shared digitally, wraps a careful piano line and head‑nodding groove around a plea not to drift too far from someone he still cares about, written just after the breakup and sung from that middle ground where you’ve accepted it’s over but haven’t moved on yet. A little further in, “Get Back” reaches for earlier days that felt easier and asks how to return to that mindset without lying about how heavy things are now, while “Hair Down” rides a looser, almost playful rhythm as he tells listeners to let go for a minute and, as he puts it, let Jesus handle the steering when life feels out of control. “Don’t Give It Up,” “Wait Forever,” “Don’t Break My Heart” and “Tangerine” circle the same knot from different angles—when to hold on, when to stop trying, how to keep a sense of humour when setbacks stack up. — Kendra Vale

NAO, Jupiter

After taking time off to recover from chronic fatigue and parenthood, East London singer NAO returns with Jupiter, a record steeped in optimism and spiritual growth. She builds the album as a companion to her breakthrough Saturn, noting that this time she wanted to focus on hope, joy, and expansion. Her writing refuses to wallow, turning it into something brighter and more assured. She doesn’t lean on one genre or mood but shifts between them. The album opens with “Wildflowers,” a song that carries a calm, free-flowing energy, setting a steady tone across the record. NAO plays with styles here, blending a sharp guitar solo in “Elevate” with the tight, tasty beats of “We All Win.” The mid‑tempo “30 Something” finds her shedding the baggage of her twenties by confessing, “I’ve been holding on to shit that don’t belong to who I am as a 30 something.” The title track uses cosmic metaphors to argue for collective healing; she repeats “We all win/When light gets in” and pleads, “Reality don’t bring me down to Earth Leave me up in orbit where my feelings won’t get hurt.” She easily moves between sounds, pulling from past decades while keeping things current. — Tai Lawson

Joy Crookes, Juniper

After her 2021 debut, Skin, earned her award nominations and viral success, South London artist Joy Crookes disappeared from the spotlight. Illness and mental health struggles delayed her follow‑up, and the four‑year gap looms large over her second album, Juniper. This record is steeped in exhaustion and defiance: on the opener “Brave,” she admits, “I’m so sick, I’m so tired, I can’t keep losing my mind,” and later in “Mathematics,” she bluntly confesses that she’s “pretty fucking miserable.” Rather than wallowing, Crookes uses these lines as entry points to songs about co-dependency, intergenerational trauma, and self-worth. “House With a Pool” examines abusive relationships with an unsentimental gaze, while “Carmen” skewers impossible beauty standards and ends with her still glowering resentfully at a so‑called perfect figure: “Why am I working double for just half of what you got?” Crookes sets these stories to a sonic palette that draws on retro-soul—electric pianos, warm bass lines, and Philadelphia-style strings—and infuses it with echoes of trip-hop and dub-reggae. The staccato piano riff in “Carmen” nods to Elton John’s “Bennie and the Jets,” and “Pass the Salt” is driven by a drum loop sampled from Serge Gainsbourg’s “Requiem pour un Con” and punctuated by a brief, explosive verse from Vince Staples. The arrangements mirror this ambivalence: hazy synths shimmer at the edges, drums swing between live‑sounding grooves and woozy loops, and her voice slips from smoky jazz phrasing to conversational raps. Juniper doesn’t chase anthems; instead, it presents a series of snapshots from a young woman wrestling with depression, identity, and the pressures of fame, finding solace in humour and melody even when the subject matter is heavy. — Tai Lawson

Clipse, Let God Sort Em Out

After sixteen years of silence, the Thornton brothers step back into the same room and decide that nothing about the Virginia they once painted has become prettier. The beats arrive almost entirely from Pharrell, stripped of the starry-eyed chrome that once glittered on Hell Hath No Fury and replaced by something colder, closer to bone. Guitars sound like rust flaking off abandoned cranes (thank you, Lenny Kravitz), drums hit like someone counting losses, and the basslines sway like faulty streetlights. Over this skeletal landscape, Pusha and Malice trade verses that feel like depositions and confessions taped on the same cassette. They mourn parents on the opener, recounting funerals where “the birds don’t sing, they screech in pain” while John Legend’s choir levitates behind them like remembered hymns. Kendrick arrives on “Chains & Whips” and the two camps swap parables about ownership, each syllable measured in shackles and stock options. Tyler brings cartoon menace to “P.O.V.”, Nas closes the record with a eulogy for the block that raised them all, and through every cameo, the brothers remain the eye of the storm—precise, unhurried, speaking of dope still hidden in baby pictures and of brothers who became cautionary tales before they turned twenty-five. There is no fat, no victory lap, only the sound of two men weighing every dollar, every body, every prayer against the scale of their own survival. — Phil

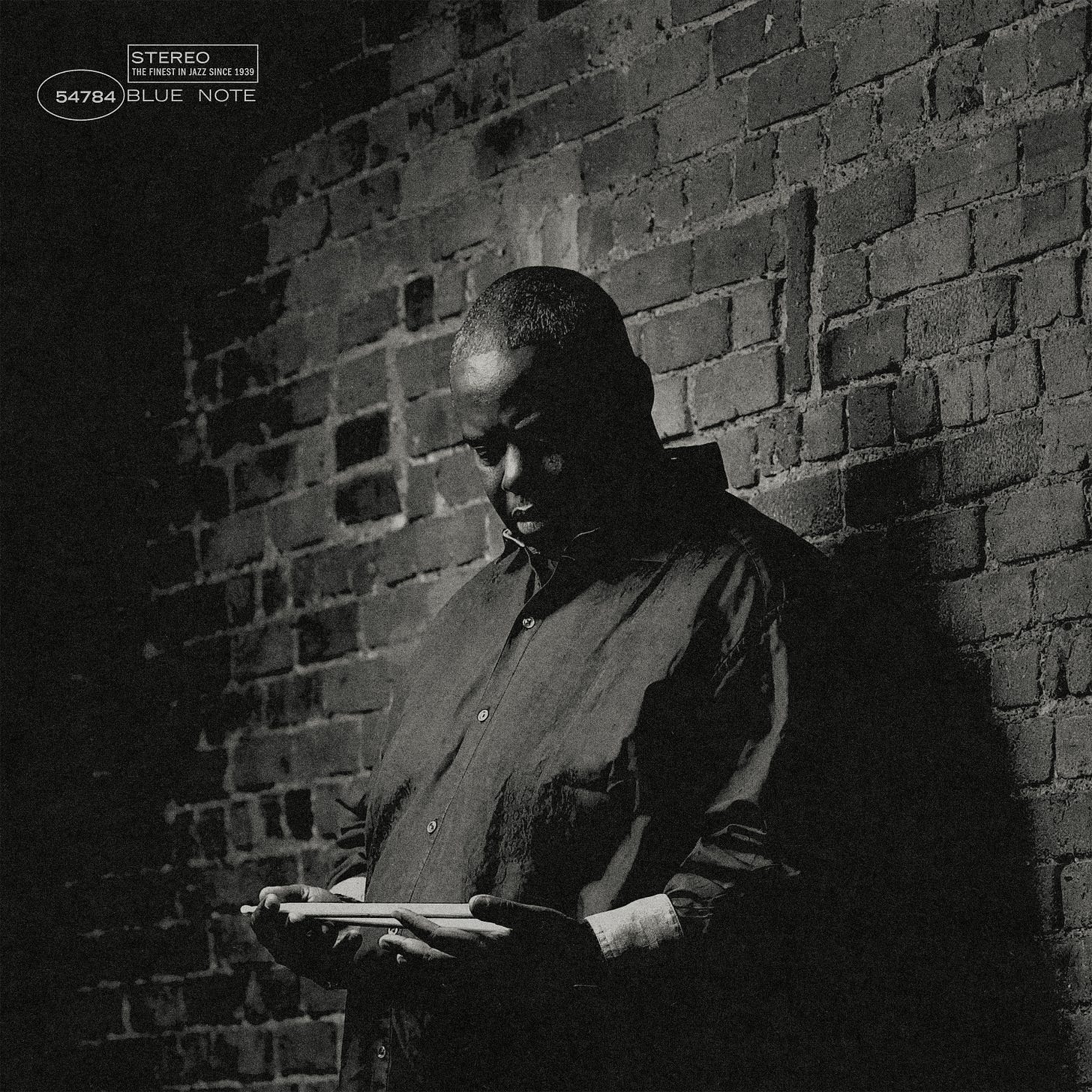

Nas & DJ Premier, Light-Years

First announced plans for a collaborative album in 2006 during a Scratch Magazine interview, Nas and Preem spent the next two decades working on the project off and on while focusing on other ventures. Their partnership began in 1994 when Premier produced three era-defining cuts on Illmatic—“N.Y. State of Mind,” “Memory Lane,” and “Represent”—establishing chemistry that became written into hip-hop’s DNA. They continued collaborating on “I Gave You Power,” “Nas Is Like,” “2nd Childhood,” and “N.Y. State of Mind Pt. II,” each track living in a class of its own as blueprint for timeless rap combining raw storytelling, razor-sharp lyricism, and production connected to New York pavement. After all these years of teasing, it felt right to end the year during the Mass Appeal campaign. Premier handles all production across the album, his signature scratch-laden instrumentals veering between throwback and timeless through “Writers,” which conjures the spirit of graffiti’s glory days, while “Nasty Esco Nasir” revisits Nas’s rap personas through an existential run-through. “GiT Ready” and “Welcome to the Underground” find Nas referencing crypto portfolios and Saudi investments, reflections of the artist as contemporary businessman, intermittently nodding to his origins as a NYCHA project kid. These references sit exceedingly far from those found on their initial studio collaborations three decades ago. “It’s Time” repurposes seminal mid-70s funk-rock, leaving “3rd Childhood” elevating the lost art of elite boom-bap, Premier’s unapologetically deep crates combining with Nas’s extensive book of rhymes to set Light-Years apart in their storied catalogs. — Rafael Greene

Earl Sweatshirt, Live Laugh Love

Earl’s path runs from the left-field sharpness of Doris through the inward focus of I Don’t Like Shit…, the fractured diary of Some Rap Songs, and the cryptic sparring of Voir Dire with Alchemist; the new record builds on that history while facing forward. The rollout leaned into mischief, but the songs are serious in their own way, sketching responsibility and doubt in brief scenes. “Tourmaline” holds one of the album’s clearest statements—“Struggle not a team sport”—and a line that places his priorities where they live now: “Keep my feet grounded for my sweet child.” “Live” walks the edge between defiance and exhaustion without reaching for a big thesis. “Infatuation” snaps phrases into place fast, more collage than lecture, and “Crisco” works as a broken-story monologue rather than a puzzle to decode. He keeps one eye on joy without pretending it cancels anything. In “Gamma (Need the <3)” he nods to Roy Ayers with a quick sun-reference, a small opening in an otherwise wary set. Around them sit titles that tell you the framing without overexplaining—“GSW vs Sac,” “WELL DONE!,” “Static,” “Heavy Metal aka Ejecto Seato!”—and the writing stays economical all the way through, which is the point. The record’s charge comes from how little he wastes. He marks fatherhood and pressure in clipped lines, lets the jokes and threats sit next to each other, and keeps the perspective tight enough that any warmth feels earned. — Nehemiah

Damon Locks, List of Demands

Damon Locks has long displayed expertise in Chicago’s creative sphere, dating back to his incumbency fronting Trenchmouth in the mid-1990s. His path has been marked by an inclination to revolutionize sound-based expression and confront social themes through music, art, and spoken word. List of Demands, released after the vinyl-only 3D Sonic Adventure from 2024 (limited to 250 copies), has often been linked to his 2023 venture with Rob Mazurek, New Future City Radio. That assumption glosses over the detailed backstory behind this multifaceted effort. Locks was commissioned to create a piece for an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, and that assignment set in motion a work that surpasses simplistic categorization. It brings forward a montage of spoken word, sampling, and instrumentation, displaying Locks’ proficiency at combining pointed commentary with stirring backdrops. Locks enumerates specific demands—beauty, form, destiny, love, time, future, and light—punctuating the last word with marked intensity. That sense of urgency rises again in “Distance,” where he describes separation as illusory and then references systemic bias in housing and the harm it produces. — Ameenah Laquita

Little Simz, Lotus

Since GREY Area, Little Simz has spent half a decade proving that personal excavation can be just as thrilling as bravado. Coming off the inward grandeur of Sometimes I Might Be Introvert and the brisk defiance of No Thank You, her latest project feels like a meditation on the trust she’s lost and the resolve she’s gained. She opens with a bold statement of renewal, trading dense orchestral flourishes for leaner funk guitar and restless live drums engineered by producer Miles Clinton James, her first studio partner since parting with her long-time collaborator. But first, “Flood,” opens with a firm reproach—“How dare you, how dare you/I was shutting down the world, and it scared you”—before guest vocalist Obongjayar flips the scene, humming through a prayer that keeps him “away from the devil’s palm” while still declaring himself “the light.” That tension between exposure and self-preservation informs the record: in “Thief,” she admits that a person she’s known her whole life (*ahem* Inflo) can still appear “like the devil in disguise,” and later she wonders, over a hush of piano and strings, “How can we sleep when there’s murders in the streets?” Simz tempers these confessions with playful edges. With “Young,” she pokes fun at her coming-of-age fantasies, bragging about “fuck-me-up pumps and a Winehouse quiff” and noting, with a grin, that she speaks “a lot of French—oui oui oui.” Throughout, she enlists trusted collaborators for support—Wretch 32 appears to help mend familial wounds on “Blood,” while the closer “Free” repeats that love remains the only true catalyst for liberation. By the time the record ends, the commandments she listed on “Flood” (never trust an outstretched hand, keep your feelings in check, look after your health) have less to do with paranoia than with preserving a self she’s fought hard to nurture. — Brandon O’Sullivan

ROSALÍA, Lux

The sole single, “Berghain,” preceded Lux by a week and immediately sparked a wave of enthusiasm on social media: ROSALÍA is (finally) back with her fourth album. This audiovisual track, accompanied by a cinematic music video, immerses us in a new world of the singer: an homage to the famous Berlin techno club—on which she sings languages in German, English, and Spanish alongside the London Symphony Orchestra —heralds the album’s orchestral and spiritual direction and reveals ROSALÍA’s deep connection to her musical past, which is more reminiscent of an oratorio than pop à la Motomami. Furthermore, this opening to her new album serves as a reminder that her academic training began at the Catalan Conservatory. Now she takes a step back to her musical roots, which still lie dormant deep within her creative expression. With each album she releases, it opens the doors to a new facet of her career—and takes at least several years to develop each of her album concepts down to the last detail. Lux is structured into four movements in the style of a modern oratorio—a structure that lends a sense of order to the album’s spiritual and emotional journey, revolving around the single as a central piece that encapsulates the transition from contemplation to catharsis. It is ROSALÍA’s greatest accomplishment and perhaps most radical personal work to date: an intersection of pop oratorio, spiritual diary, and sonic laboratory. — Charlotte Rochel

Venna, MALIK

Growing out of two EPs, Venna made his name as a saxophonist and producer moving between jazz and UK rap. MALIK feels like the moment when all the fragments of his sound—his saxophone roots, his love of soul, rap, bossa nova—finally align into something expansive and resonant. Born Malik Venner, he took his middle name from his mother’s wish that he grow into a leader, and now this release is a coming‑of‑age project and an invitation to “let go, be present and submit to sensory experiences.” The record opens up conversations about identity, legacy, and belonging; named by his mother long before the album existed, MALIK becomes a becoming. Jorja Smith, MIKE, Smino, and Leon Thomas help voice their surroundings, add layers of testimony, even when the instrumental moments speak most. There are warm acoustic guitars, percussive textures that appear intermittently, live horns paired with electronic elements, and moments of softness that shift into urgency without losing the thread. As a debut, it stands not just as an arrival, but also as a letting in of fragility, a witnessing of someone building, risking, holding both light and shadow. It belongs among the essential albums of this year, which are redefining what “modern jazz/fusion/cross-genre soul” can be. — LeMarcus

Lady Gaga, Mayhem

With Lady Gaga, she has spent the last decade toggling between conceptual eras that either succeed wildly or collapse under their own ambition, from the political flag-waving of Born This Way to the healing arc of Chromatica to last year’s Harlequin, which worked specifically because she stopped trying to mythologize everything. Mayhem strips away even more pretension, dialing back to the artifice-as-commentary approach of The Fame without getting trapped in nostalgia. Gaga handles executive production alongside Michael Polansky and Andrew Watt, working primarily with Watt, Cirkut, and Gesaffelstein to create what she describes as a “chaotic blur of genres” rooted in synth-pop with industrial dance influences pulling from electro, disco, funk, industrial pop, rock, and pop rock. “Abracadabra” follows with an interpolation of Siouxsie and the Banshees’ “Spellbound,” channeling 80s new wave through contemporary production. “Perfect Celebrity” addresses her own image with anger, singing “I’ve become a notorious being/Find my clone, she’s asleep on the ceiling” about the split between Stefani and Lady Gaga. “Garden of Eden” snaps along like prime RedOne-era material, a sweet treat aligned so closely with The Fame aesthetic it could slot into that tracklist. “Shadow of a Man” struts through reflections on always being the only woman in rooms full of men, building tension throughout before releasing into its chorus. — Jill Wannasa

Zara Larsson, Midnight Sun

Swedish pop star Zara Larsson has chased pop stardom since her early teens, releasing platinum singles and the high‑concept album Venus in 2024. Midnight Sun charts a simpler course by stripping away elaborate narratives to deliver 10 tracks of lean, starry‑eyed scandipop. Coming in at just over half an hour, it finds Larsson trusting her instincts and reuniting with longtime collaborator MNEK, whose work across the album seems to have reignited her confidence. “Pretty Ugly” revolves around a gang‑vocal hook that refuses to leave your head and surges forward on bright piano chords. The title track swells with glittering hooks and club beats, creating an atmosphere of euphoria and endless daylight. “Crush” and “Eurosummer” fuse festival‑ready choruses with tight, intelligent writing, while “Saturn’s Return” bathes Larsson’s voice in waves of synthesizer until the song feels like an astral projection. The album may be short, but its focus allows each song to stand on its own as an invitation to dance or shout along; Larsson is honing in on what she does best, delivering unabashedly joyous pop built to ignite dancefloors and festival crowds. In returning to simplicity, she reminds us why she became a star in the first place. — Oliver I. Martin

KIRBY, Miss Black America