The 50 Best Jazz Albums of 2025

A multigenerational conversation in sound. You’ll hear legends and newcomers weaving fresh narratives; jazz in 2025 will not be pinned down. Expect anything but the expected.

As the calendar turns to 2025, jazz finds itself in exceptional form—restless, inclusive, and delightfully unpredictable. From tape-saturated church studios to high-concept chamber performances, artists are reimagining what a jazz record can feel like. This year’s highlights go beyond genre borders without leaving the music’s core spirit behind, inviting you to lean in and discover something unexpected at every turn. Below, we’ve gathered the most compelling albums that define jazz’s expansive present and promising future.

José James, 1978: Revenge of the Dragon

José James cut the entire set to two-inch tape inside Dreamland, a converted church whose wooden rafters trap cymbal spray and ambient hiss, so the record breathes like a crowded club rather than a DAW grid. BIGYUKI’s analog synths fizz against Jharis Yokley’s cracked-rim snare while a three-horn frontline of Takuya Kuroda, Ebban Dorsey, and Ben Wendel punches lines that feel lifted from a Shaw Brothers soundtrack. “Tokyo Daydream” drapes that brass over a rubber-band bass ostinato, then slips into double-time handclaps that evoke neon alleys at midnight. The Michael Jackson cover “Rock With You” slows to half-speed, James stacking his voice into woozy harmonies while a dubbed-out clavinet wobbles beneath muted trumpet. “They Sleep, We Grind (for Badu)” filters a clav groove through tape echo, echoing its mantra-like hook across speaker cones until it feels more ritualistic than a song. Original “Rise of the Tiger” rips forward with fuzz bass and kung-fu dialog samples, paying tribute to James’s own martial-arts practice. “Last Call at the Mudd Club” ends on a bent tenor-sax scream that fades into the studio’s natural reverb, leaving only creaking floorboards and tape hiss as the lights cut. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Mary Halvorson, About Ghosts

On About Ghosts, Mary Halvorson leans into that large‑ensemble thinking, writing for brass, vibes, rhythm section, and her own crooked guitar in a way that lets the group move like a single organism rather than a backdrop for solos. She’s tested every way it might twist, fracture, and still hold together, and she’s spent the last decade slowly building bands big enough to carry those questions without crushing them. You can hear it when the horns and vibraphone lock into clear, almost singable lines, and then her guitar nudges a chord sideways, forcing everyone to adjust on the spot instead of just sailing through the chart. Pieces that move like ballads keep a tenderness at the center even as the harmony slides under your feet; more jagged tunes hang on riffs and pulses that sound almost rock‑steady until a counter‑line darts in and pulls them toward something stranger. The record ends up feeling like her trying to keep emotional directness and structural mischief in the same space, writing songs you could hum on the way home while constantly prodding the band to see how far those songs can bend before they snap. — Nehemiah

Joe Armon-Jones, All the Quiet (Part II)

Joe Armon-Jones handles writing, production, and mixing, fusing jazz harmony with dub atmosphere and easygoing funk grooves on his own terms with this sequel. “Acknowledgement Is Key” lets Hak Baker recount personal struggles over sparse keys and rounded bass, turning conversational snippets into central hooks. “Westmoreland” brings Asheber’s resonant baritone atop a rhythm inspired by sound-system culture, while analogue hiss signals Armon-Jones’s fondness for tactile studio character. Greentea Peng and Wu-Lu share space on “Another Place,” trading melodic lines that glide rather than clash. Yazmin Lacey’s appearance on “One Way Traffic” offers a brief lift before the band settles back into steady motion. Nubya Garcia threads short sax phrases through several sections, never overstaying. Drummer Kwake Bass locks a relaxed pocket that lets keyboard voicings float. Instead of chasing climaxes, Armon-Jones allows ideas to breathe, rewarding jazz fans who stay for detail. — Harry Brown

Rabbath Electric Orchestra, Amall

François Rabbath has lived most of his life with the bass at the center of everything. Every project seems to open another border. Amall takes that instinct and runs it through an electric filter, with his son Sylvain helping build a setting where thick grooves, keys, and guests fold into an “orchestra” that’s closer to a plugged‑in family band than a conservatory ensemble. “Sevillana” and “Twin City” ride bass figures that feel both deeply learned and casually funky, as if decades of bow work and classical study are distilled into lines meant for dancing, not juries. When the horns and guest soloists come in, they don’t grandstand so much as ride the current he sets, dropping phrases over rhythms that nod to North Africa, Paris, and New York without turning any of them into a postcard. What you keep noticing is how unhurried he sounds inside all that gloss, and even when the band heats up, his playing moves with the calm of someone who knows exactly which note will tug the whole arrangement in a new direction. — LeMarcus

James Brandon Lewis, Apple Cores

When you talk about James Brandon Lewis, he has been building his own private system for a while now, talking about intervals and rhythms like they’re molecules you can recombine, but the thing that keeps cutting through is how physical his tenor feels. Interesting, right? Apple Cores distills that into a trio with bass and drums, where every line he plays has to push against air, groove, and silence at once. Tunes like “Apple Cores #1” or “Prince Eugene” start from tight little rhythmic cells that could easily slide into straight funk or dub, and then he worries them until the patterns open up and the horn starts arguing with the beat instead of sitting on top of it. “Five Spots to Caravan” pulls history into the room without nostalgia, nodding toward Ornette and specific places attached to his name while the band keeps things stubbornly in the present, leaning on tom‑heavy patterns and basslines that want to loop. Even when the group drops into something as plainly titled as “D.C. Got Pocket,” there’s always a moment where he pushes the tenor into a cry or a shiver that doesn’t resolve neatly, like he’s reminding himself that groove and freedom are the same problem approached from different sides. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Juicy J & Endea Owens, Caught Up In This Illusion

Endea Owens’ Juilliard pedigree and Cookout ensemble meet a veteran rapper who’s turned mixtape endurance into a decades-long brand. Primarily an instrumental piece, Juicy J raps in a measured pocket while a band with real swing moves around him, and the writing leans toward grown stakes, whether he’s talking custody runs in “Taking My Kids to School” or setting boundaries in “Litigation vs Loyalty.” Cory Henry’s keys and Kenneth Whalum’s horn lines answer the verses like trusted sidemen, and Nia Drummond’s voice steps in as conscience rather than gloss; “Drinks On Me at the Blue Note” reads the room and still makes space for a hook. Endea Owens isn’t here as ornament—her bass sets tempo and attitude, a reminder that she’s stamped big stages and earned major hardware—and that steadiness keeps the album honest about risk and restraint. The choice to put both names on the spine matters, where a rapper who knows momentum, a bandleader who knows form, and a set of tracks that let testimony sit next to groove without shouting for approval. — Nehemiah

Nels Cline, Consentrik Quartet

Nels Cline’s fourth Blue Note release doesn’t sound like his usual guitar-driven work. This time, with the Consentrik Quartet, Ingrid Laubrock’s saxophone steps up front, and Cline seems fine playing a quieter role. The group, rounded out by Chris Lightcap on bass and Tom Rainey on drums, first played together at The Stone in Brooklyn, a free-improvisation night just before the pandemic locked everything down. Cline wrote the album in that forced pause, shaping it into something that feels tied to Blue Note’s past, like the ‘60s records from Eric Dolphy or Andrew Hill. It’s got a steady, meditative pulse built on the organic sound of post-bop from that era. But it’s not all mellow—“Satomi” throws in some wild punk-jazz moments that pull you out of the calm. — Nehemiah

Kassa Overall, CREAM

Kassa Overall has always heard jazz and rap as parts of the same nervous system. He switches between trap‑leaning drums and swing patterns without asking permission, so a set of versions of ‘90s hip‑hop songs feels less like a detour and more like him laying his cards on the table. Sure enough, he delivers. On CREAM, he takes tracks everybody knows by muscle memory—“Big Poppa,” “C.R.E.A.M.,” “Nuthin But a ‘G’ Thang,” “Rebirth of Slick,” “Back That Azz Up,” “SpottieOttieDopaliscious”—and pulls them apart until only the contour of the hook and the feel of the original beat are left, then rebuilds around live drums, keys, and horns. Sometimes he leans close to the source, letting the bassline or chord movement sit almost unchanged while the band plays with time and texture around it; other times he handles the tune like a sample that never existed, starting from a small rhythmic idea and letting fragments of the original vocal cadence appear in the way the instruments phrase. Because he’s rapping, drumming, and producing, he can shift point of view mid‑track: one moment you’re inside a drummer’s head, counting subdivisions, and the next you’re hearing how a teenager in love with these records might have freestyled over them in a bedroom. It ends up sounding less like a “jazz covers hip‑hop” gimmick and more like a working drummer showing how those records rewired his sense of swing and harmony in the first place. — Phil

Theo Croker, Dream Manifest

Theo Croker pulls themes from a dream journal, translating them into nine concise instrumentals and vocal collaborations. “Prelude 3” pairs piano with muted trumpet, establishing a relaxed conversation before fuller grooves appear. Estelle and Kassa Overall share gentle lines on “One Pillow,” set against brushed snare and soft bass that keep the mood close. “64 Joints” runs longer, allowing Tyreek McDole to float over slow keys while the rhythm section holds steady. “Up Frequency (Higher)” edges pace upward, yet air remains in the mix for horn flourishes. Gary Bartz joins “Light as a Feather,” trading concise phrases with Croker that favor dialogue over display. MAAD and Malaya add subtle R&B shades on “High Vibrations,” widening the palette without crowding instruments. Croker prefers analog warmth, evident in rounded horn edges and lightly saturated keys. Throughout, Croker prioritizes emotional clarity and collective balance over technical parade, inviting listeners into a quietly imaginative sound world. — Nehemiah

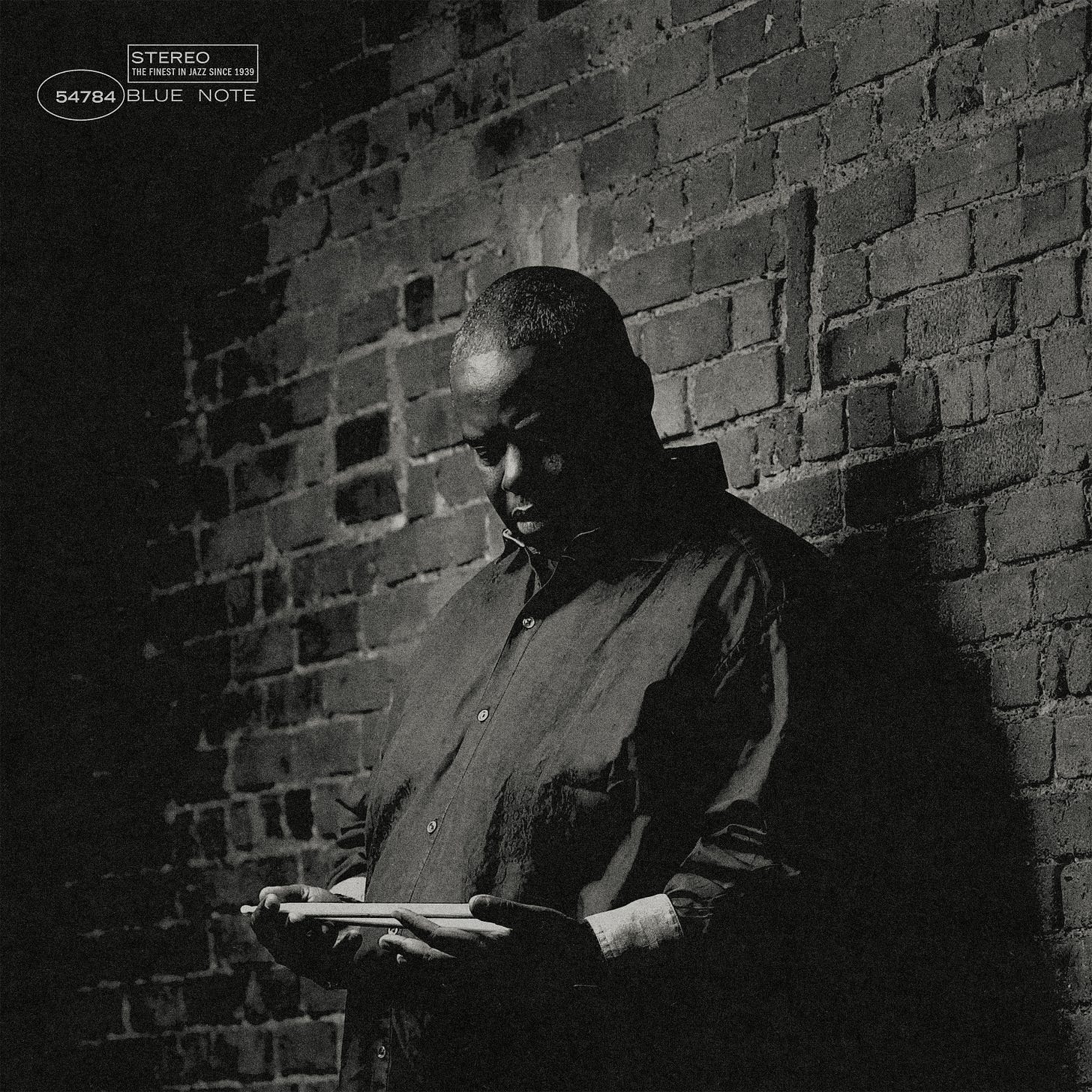

Gary Bartz & NTU: The Eternal Tenure of Sound: Damage Control

Gary Bartz has been a standard‑bearer in jazz since his days with Art Blakey, and he has spent his eighties demonstrating that experimentation doesn’t stop with age. After a dozen years away from the studio, he returned by cashing out his retirement savings and taking a sabbatical from his teaching post to fund the first instalment of a trilogy. Recorded at the North Hollywood home studio of his godson and producer Om’Mas Keith, the album sees the NEA Jazz Master, now in his mid‑80s, assemble a cross‑generational band featuring pianist Barney McCall, drummer Kassa Overall, and guests such as Kamasi Washington, Terrace Martin, Nile Rodgers, and Theo Croker. He reimagines R&B and soul tunes that he often sings in the shower, including Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Fantasy,” Curtis Mayfield’s “The Makings of You,” Midnight Star’s “Slow Jam,” and DeBarge’s “Love Me in a Special Way.” Each cover is a springboard for improvisation rather than a faithful reprise: “Fantasy” opens with shimmering keyboards and harp while Bartz’s alto sax dances around a melody before he shares a gentle vocal refrain with Rita Satch. “One Hundred Ways,” associated with Quincy Jones, grooves as guitars weave counter‑lines around his searching phrases, and in a tribute to his mentor McCoy Tyner, he turns “In Search of My Heart/Love Surrounds Us Everywhere” into a ten‑minute funk workout where horns trade solos over a churning rhythm section. Bartz uses it as an opportunity to connect with a younger generation of musicians and listeners, proving that an 84‑year‑old saxophonist can still find new stories inside old songs. — Nehemiah

Charles Lloyd, Figure in Blue

For years, Charles Lloyd has been circling the same themes—memory, devotion, the blues hidden inside everything—for so long that at this point every new project feels like another pass at the same long conversation, and that repetition is the point. It’s no surprise that Figure in Blue finds him with just piano and guitar, Jason Moran and Marvin Sewell, a trio small enough that you can hear every intake of breath around his horn. He moves through hymns, Ellington pieces, older tunes from his book, and new sketches as if they’re all chapters of one story about aging, leaving long notes hanging while Moran puts just enough harmony underneath them to keep them from floating off. Sewell’s bottleneck guitar drags more earth into the room, tugging spirituals toward delta territory and making the ballads feel less like abstractions and more like memories of specific rooms and people. When he revisits something like “The Ghost of Lady Day” or “Blues for Langston,” the themes are intact, but the edges are softer, as if he’s less interested in making a statement than in seeing what still resonates in his hands right now. The whole album plays like someone who’s accepted that he can’t sum up his history and instead keeps returning to a few melodies and prayers, turning them over until they glow in the quiet. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Sumac & Moor Mother, The Film

Conceived as an “imaginary documentary” score, this 50-minute behemoth fuses Sumac’s free-form post-metal with Moor Mother’s oracular spoken-word. Recorded live in single takes, movements flow like reel changes: “Scene 2: The Run” lurches from hi-hat shrapnel into sludge-bass avalanches, while opener “Camera” finds Moor Mother chanting “I want my breath back” against detuned drones, a visceral nod to present-day suffocation—literal and political. The closer, a 16-minute tidal wave of feedback and free-jazz cymbal wash, leaves her whispering “memories from planet Earth,” as if panning over post-apocalyptic credits. Rather than riff-plus-vocal stacking, the collaboration melts both vocabularies into what reviewers are calling free-metal: structure-less yet composed, spiritual yet furious. — Nehemiah

Ledisi, For Dinah

Following salutes to Nina Simone in earlier parts of the decade, Ledisi now works with Dinah Washington, and a tight book of standards demonstrates how a great singer reads a lyric as lived fact and not museum text, and the style is a tribute to Washington without impersonation. “You Don’t Know What Love Is” inclines to disorientation and heartache, and leaves the questions unspecified long enough to hurt; then “You’ve Got What It Takes” answers with no less certainty or explanation than two people would in the morning than the myth does at night. In “Caravan,” the pictures are directed off into space, away towards traveling and eating stuff, and in “Let’s Do It,” the wordplay remains light and humorous with no winking or grimacing, and in “This Bitter Earth,” the sadness remains in silence, waiting till the bitterness turns into useful strength. She pins all that transformation through “What a Difference a Day Made” not as a flashback, but rather as a turn of events in the present, and writing revolves around the mere fact that one day can actually change a life. — LeMarcus

Brandon Woody, For the Love of It All

Woody’s trumpet tone sits somewhere between Clifford Brown’s caramel warmth and Christian Scott’s breathy edge, but his compositional sense is firmly of the present: trap-lilted hi-hats coexist with modal piano clusters and snatches of spoken-word prayer. The album is structured like a church service turned block party—opening fanfare, communal affirmation, ecstatic peak, contemplative benediction. Upendo, his long-running quartet, locks into polyrhythms that reflect Baltimore’s go-go legacy even as synth textures nod toward cosmic-jazz futurism. On “Never Gonna Run Away,” Woody quotes “Lift Every Voice and Sing” before vaulting into a double-time solo that feels like an asphalt sprint through North Avenue at dusk. He refuses the jazz-world trope of geographic migration, choosing instead to root the music in the city that raised him; the result is a record that radiates place-based love without turning parochial, achieving universality through hyper-local detail. — Phil

Brandee Younger, Gadabout Season

Brandee Younger centers her harp on circular themes that invite a calm, reflective state of mind. Rashaan Carter’s bass and Allan Mednard’s drums supply light propulsion while keeping clear air around the strings. Recorded partly on a restored instrument once used by Alice Coltrane, the set honors lineage without leaning on nostalgia. “Reckoning” opens with a brief, searching figure that reappears in subtle variations later on. Shabaka’s flute on “End Means” slips in like a soft breeze, coloring the mix without turning the spotlight. “Breaking Point” toughens the groove with clipped accents while still leaving room for melodic breathing. Younger wrote every piece, and her intent shows in the disciplined pacing. She avoids flashy runs, aiming instead for motifs that bloom through repetition. Short overdubbed vocal sighs drift through “BBL,” hinting at R&B influence without a full stylistic pivot. Sessions took shape in her Harlem apartment, lending casual intimacy to the recording. By steering away from grand gestures, Younger underlines the harp’s conversational power on Gadabout Season that feels like time well spent in thoughtful company. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Etienne Charles, Gullah Roots

After spending time in Gullah Geechee communities in the Carolinas and Georgia, Etienne Charles folds ring shouts, church songs, work rhythms, and local stories into a suite that moves between horns‑and‑rhythm‑section passages and more stripped‑down moments where voice and drums carry most of the weight. He has been tracing lines through the Black Atlantic for years, tying Carnival, calypso, New Orleans, and straight‑ahead jazz together through his trumpet and arranging, but Gullah Roots narrows the lens to a specific strip of coast and the people who held on there. You can hear fieldwork in the way certain chants and call‑and‑response patterns are left rough around the edges, not smoothed into polite choruses, and in how some tracks feel built on the cadence of speech rather than conventional song form. When the full band kicks in, those fragments ride on top of backbeats, horn lines, and bass figures that pull in calypso and second‑line currents he already knows how to steer. Instead of pinning this culture to a museum wall, he keeps asking how it moves right now—how these rhythms and stories might sound tumbling out of a club PA or a festival stage while still carrying the memory of land loss, language, and survival. — Ameenah Laquita

Ambrose Akinmusire, Honey from a Winter Stone

Sometimes, it starts with a place. For Ambrose Akinmusire, that place is Oakland, California: a city whose complexities—cultural, social, and sonic—have shaped not just who he is as a person but who he is as a musician. When Akinmusire released Origami Harvest in 2018, it was the clearest articulation yet of that wide musical embrace: a head-on collision of jazz improvisation, hip-hop verse, and modern classical strings. Now, with Honey from a Winter Stone, Akinmusire returns to that hybrid world with even greater confidence. He added vocalist Kokayi and synthesist Chiquitamagic to this already potent mix, creating a multi-genre tapestry where Mivos remains central and essential, not an afterthought. In these new pieces, Akinmusire grapples with issues he has named and claimed as personal: colorism, erasure, and the question of who has the right to speak for the Black community. It might look like jazz, hip-hop, and modern chamber music on paper, but, as with much of Akinmusire’s work, the reality exceeds any single category. — Nehemiah

Chicago Underground Duo, Hyperglyph

As a duo, Rob Mazurek and Chad Taylor have been in the laboratory for so long that every new record arrives with its own little chemistry set. You never quite know whether you’re getting groove studies, noise storms, or some sideways mix of the two. Hyperglyph sounds like them deciding that an eleven‑year gap doesn’t mean starting over, just picking up old threads with new tools. Trumpet, drums, mbira, and electronics are all in play, but the focus is on patterns that repeat just long enough to get lodged in your body before an odd accent, a synth smear, or a sudden dynamic spike skew them. Some pieces lean into rolling, West African‑inflected cycles where Taylor’s drumming sets up a trance and Mazurek’s horn becomes a shard of melody poking through; others head straight into smeared‑out abstraction, with tones and textures stacking until you lose track of what’s acoustic and what’s processed. What keeps it from floating away is their shared sense of structure—you can feel them listening for when to pull back to a simple figure, when to blow the roof off, and when to let the music simmer low for minutes at a time. — Harry Brown

Dave McMurray, I LOVE LIFE even when I’m hurting

Came from a scene where jazz, blues, funk, soul, rock, punk, and electronic music collide, his five-decade journey spanning Was (Not Was), the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Iggy Pop, and nine years in Kid Rock’s Twisted Brown Trucker Band, Dave McMurray studied urban studies and psychology at Wayne State University before music overtook his mental health counseling career. I LOVE LIFE even when I’m hurting arrives as affirmation after deep discussion about a friend worn down by illness who gave up and died alone, McMurray’s unyielding response becoming the album’s narrative: “Man, I love life even when I’m hurting.” “This Life” opens with brawny, iridescent tenor saxophone tone before “The Jungaleers” kicks into ebullient Afrobeat groove concocted by drummer Jeff Canady and percussionist Mahindi Masai, propelled by none other than Don Was on bass—the Blue Note president and longtime collaborator whose relationship with McMurray spans four decades back to Was (Not Was)’s 1981 debut. “7 Wishes 4 G” percolates to a hazy soul-jazz deep house groove worthy of Moodymann or Norma Jean Bell, conceived in 7/4 odd meter while still feeling like house music and sounding like Pharoah Sanders’s “Astral Traveling.” “We Got By,” Al Jarreau’s soul-jazz ballad featuring Detroit’s Kem, brims with themes, while the Yusef Lateef cover “The Plum Blossom” completes a triptych honoring lineage while refusing museum treatment—Detroit’s sonic DNA recombined into positivity. — Nehemiah

William Hooker, Jubilation

With Jubilation, this set catches William Hooker live with trumpet, alto sax, guitar, and bass, stretching a suite across long movements that feel less like songs and more like weather patterns he’s steering from the kit. He’ll start from small, almost pointillist gestures—cymbal taps, brushed rolls, short phrases from the horns—and gradually push the volume and density up until everyone is in full roar, then drop back without ever losing focus. Pieces like “The Stare” or “Laws of Heredity” unfold in stages: solos emerge, collide, and give way to collective improv where no one voice dominates for long, all of it anchored by his sense of pacing. You can hear how much time he’s spent on the fringe of multiple scenes in the way he refuses easy payoff. The climaxes arrive, but they’re part of a longer arc about tension, release, and what it means to keep a band locked into risk rather than safety. — Imani Raven

Tom Skinner, Kaleidoscopic Visions

When Tom Skinner records under his own name, you can hear him sorting through that whole pile. He has been the quiet engine behind other people’s projects for years, sitting at the drum kit while bands move between Afro‑Caribbean patterns, post‑punk energy, and spiritual‑leaning jazz. The whole record keeps circling questions about fear, responsibility, and self‑definition without spelling them out, using shifts in meter, texture, and ensemble size as they think them out loud. Kaleidoscopic Visions feels like him putting those threads on the table—chamber‑like writing for bass, cello, and reeds; uneasy grooves that never quite settle; guest voices that step in like characters in a play—and asking what still feels true now that he’s in midlife. The title track comes off like a thought captured at the piano and then expanded for the band, with drums nudging the harmony forward instead of just marking time. He lets pieces like “There’s Nothing to Be Scared Of” or “Margaret Anne” move slowly enough that you can hear the air between hits, then pulls in Meshell Ndegeocello or other guests to stretch sections out into something closer to song form. — Harry Brown

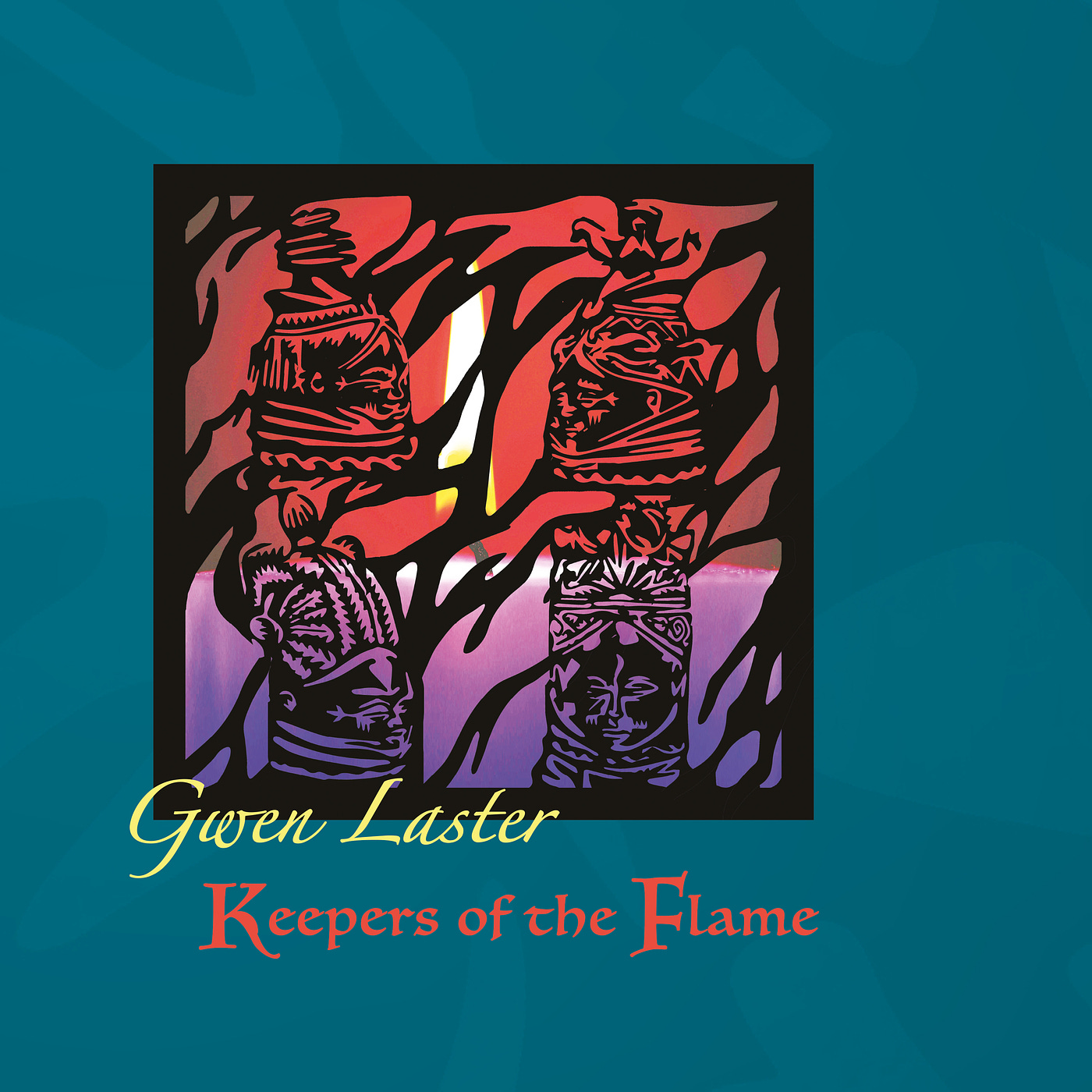

Gwen Laster, Keepers of the New Flame

Themes inspired by African hero myths, grief, and focused attention show up as tight motifs that the group plays in unison before breaking them apart through improvisation. Gwen Laster has been doing the work of putting strings at the center of Black improvising music for a long time, running bands, teaching, and writing pieces that carry as much social charge as they do melodic pull. With New Muse 4tet on Keepers of the New Flame, she goes all in on that idea, writing for violin, viola, cello, and drums like they’re a small choir tasked with holding stories about the African diaspora, activism, and daily survival. Collective pieces where the whole band composes in real time keep that tension between sorrow and forward motion alive, with the drummer sometimes just coloring the edges and other times pushing the strings into rougher, more percussive territory. Instead of leaning on lyrics or explicit slogans, she lets the harmonies, dissonances, and repeated figures carry the weight of protest and persistence, trusting the quartet’s sound to say what words would flatten. — Ameenah Laquita

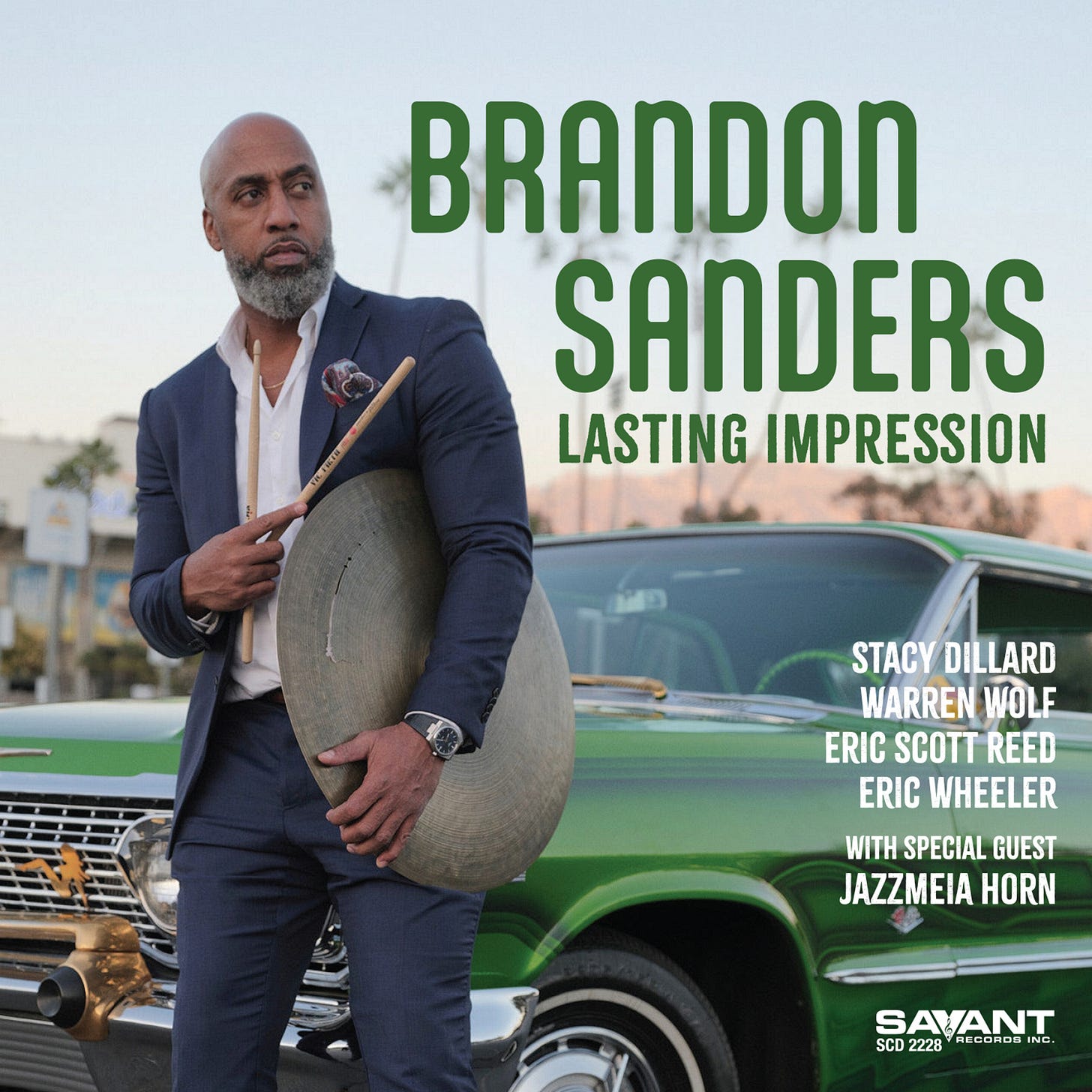

Brandon Sanders, Lasting Impression

Brandon Sanders was 25 years old before he ever picked up drumsticks, releasing his debut Compton’s Finest in 2023 at age 52, but his grandmother Ernestine Parker ran the Casablanca, a Kansas City club where young Brandon spent summers from the mid-1970s through late ‘80s surrounded by Jimmy Smith, Grant Green, and Lou Donaldson—not classroom instruction but communion, baptism in sound. Between those formative summers and his eventual arrival as a bandleader, Compton DJ, and social worker, decades as a college basketball player, and experiences that now enrich and pour forth from his music. Lasting Impression, his third Savant Records release, features vibraphonist Warren Wolf, pianist Eric Scott Reed, saxophonist Stacy Dillard, bassist Eric Wheeler, and Grammy-nominated vocalist Jazzmeia Horn, the constellation designed to linger in memory. Bobby Hutcherson’s “8/4 Beat” opens as a showcase for Wolf, while Reed’s originals “Shadoboxing” and “No BS for B.S.” balance Sanders’ own buoyant title track and poignant “Tales of Mississippi.” Dillard’s take on Mal Waldron’s “Soul Eyes” dives deep into longing and beauty. Horn’s singular style combines the timeless with the futuristic on the Gershwins’ “Our Love Is Here to Stay” and Stevie Wonder’s “Until You Come Back to Me.” — Imani Raven

Butcher Brown, Letters from the Atlantic

Hailing from Virginia, Butcher Brown has carved out a space as a genre-blending quintet. The lineup includes Marcus “Tennishu” Tenney on trumpet and saxophone, Morgan Burrs on guitar, Corey Fonville on percussion, Andrew Randazzo on bass, and DJ Harrison on keyboards. Their twelfth album, Letters from the Atlantic, and fifth for Concord continues their practice of fusing musical styles. Starting with “Seagulls,” the record features soft, wave-like chords paired with a broken beat, creating an atmospheric entry point. Over twelve tracks, the band produces grooves that maintain a laidback feel while incorporating varied textures and rhythms. Their ease of moving between genres highlights a strong grasp of multiple musical forms. With its detailed production and focused performances, Letters from the Atlantic is a key moment in Butcher Brown’s catalog, reflecting their evolving approach to musicianship. — Reginald Marcel

Damon Locks, List of Demands

Damon Locks has long displayed expertise in Chicago’s creative sphere, dating back to his incumbency fronting Trenchmouth in the mid-1990s. His path has been marked by an inclination to revolutionize sound-based expression and confront social themes through music, art, and spoken word. List of Demands, released after the vinyl-only 3D Sonic Adventure from 2024 (limited to 250 copies), has often been linked to his 2023 venture with Rob Mazurek, New Future City Radio. That assumption glosses over the detailed backstory behind this multifaceted effort. Locks was commissioned to create a piece for an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, and that assignment set in motion a work that surpasses simplistic categorization. It brings forward a montage of spoken word, sampling, and instrumentation, displaying Locks’ proficiency at combining pointed commentary with stirring backdrops. Locks enumerates specific demands—beauty, form, destiny, love, time, future, and light—punctuating the last word with marked intensity. That sense of urgency rises again in “Distance,” where he describes separation as illusory and then references systemic bias in housing and the harm it produces. — Ameenah Laquita

Venna, MALIK

Growing out of two EPs, Venna made his name as a saxophonist and producer moving between jazz and UK rap. MALIK feels like the moment when all the fragments of his sound—his saxophone roots, his love of soul, rap, bossa nova—finally align into something expansive and resonant. Born Malik Venner, he took his middle name from his mother’s wish that he grow into a leader, and now this release is a coming‑of‑age project and an invitation to “let go, be present and submit to sensory experiences.” The record opens up conversations about identity, legacy, and belonging; named by his mother long before the album existed, MALIK becomes a becoming. Jorja Smith, MIKE, Smino, and Leon Thomas help voice their surroundings, add layers of testimony, even when the instrumental moments speak most. There are warm acoustic guitars, percussive textures that appear intermittently, live horns paired with electronic elements, and moments of softness that shift into urgency without losing the thread. As a debut, it stands not just as an arrival, but also as a letting in of fragility, a witnessing of someone building, risking, holding both light and shadow. It belongs among the essential albums of this year, which are redefining what “modern jazz/fusion/cross-genre soul” can be. — LeMarcus

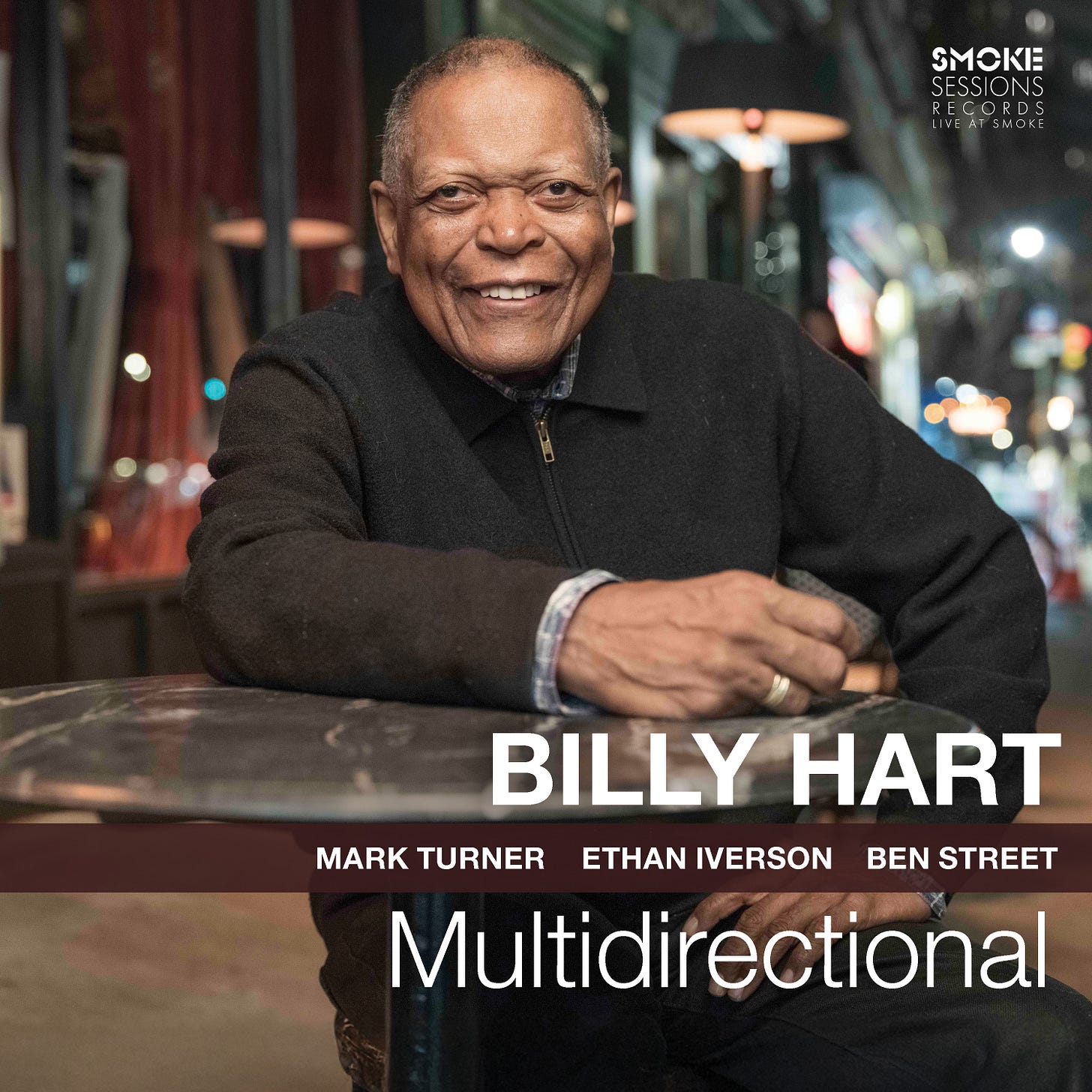

Billy Hart, Multidirectional

Meet Billy Hart: Multidirectional finds his long‑running quartet responding to that idea onstage, taking tunes they’ve carried for years and stretching them in several directions at the same time rather than driving toward a single, tidy climax. Mark Turner, Ethan Iverson, and Ben Street know his language so well that a ballad like “Song for Balkis” can start in a hushed, mallet‑heavy sway and slowly tilt into more turbulent territory without anyone sounding surprised. Pieces the group first tackled in the studio, like “Amethyst” or “Sonnet for Stevie,” open up into longer arcs where Hart’s cymbal crashes and tom flurries keep changing the underlying feel, inviting the others to abandon straight lines for spirals. Even the take on “Giant Steps” refuses to behave like a shop‑window display of chops; the familiar chord cycle becomes one more landscape for Hart’s shifting pulses and Turner’s probing lines. What you hear most clearly is a band that trusts an elder drummer enough to let him keep redrawing the grid in real time. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Moses Yoofee Trio, MYT

As clubs across Germany grappled with unforeseen closures and capacity limits, a remarkable trio coalesced in cramped rehearsal spaces. In 2020, Moses Yoofee, already recognized for his resourceful improvisations, enlisted drummer Noah Fürbringer and bassist Roman Klobe-Barangă to experiment with a fresh approach to groove. Their chemistry became apparent when they tackled early sketches that combined hip-hop motifs with graceful chordal underpinnings. Spread across 13 tracks, MYT charts a route through soulful chords, hectic drum patterns, and warm bass lines. Fürbringer’s percussive flair is especially evident on “Push,” where synthesizer textures swirl around his unrelenting hits, while “Bond” sees him lock into frenetic double time that verges on disorienting yet remains grounded. Klobe-Barangă, for his part, displays an unwavering presence, anchoring the low end even when the band shifts abruptly from mellow interludes to thundering crescendos. Meanwhile, Yoofee seizes every opening to insert melodic color or sudden harmonic adjustments, dissolving barriers between the band’s jazz foundation and the influences they absorb from hip-hop or modal experimentation. — LeMarcus

Johnathan Blake, My Life Matters

Commissioned by The Jazz Gallery Fellowship Series, Johnathan Blake returns to recording after years of building respect among jazz insiders, utilizing drumming, composition, and suite-writing to speak to heritage and urgency. His new work confronts what invisibility and injustice do to one’s sense of self by paying homage to ancestors, to familial values, to protests still unfinished. “Last Breath” channels the memory of Eric Garner, and “Can You Hear Me?” pulses with the voices of those whose voices have been stifled. Risk shows up in blending narrative interludes with intense instrumental suites; some passages might feel confrontational for listeners expecting smooth jazz, but these tensions are essential. A core group—Dayna Stephens (sax/EWI), Fabian Almazan (keys/electronics), Dezron Douglas (bass), Jalen Baker (vibes)—answers Blake’s call with both fire and space, and guests like Bilal and DJ Jahi Sundance punctuate moments with vocal humanity and sampled sound. The suite weaves between grief and hope, tragedy and resilience without settling fully into either, which makes it more alive. Among his catalog, this feels like one of the boldest statements: it doesn’t repeat but extends what he’s built, speaking not only for his life but for lives too often minimized. — Reginald Marcel

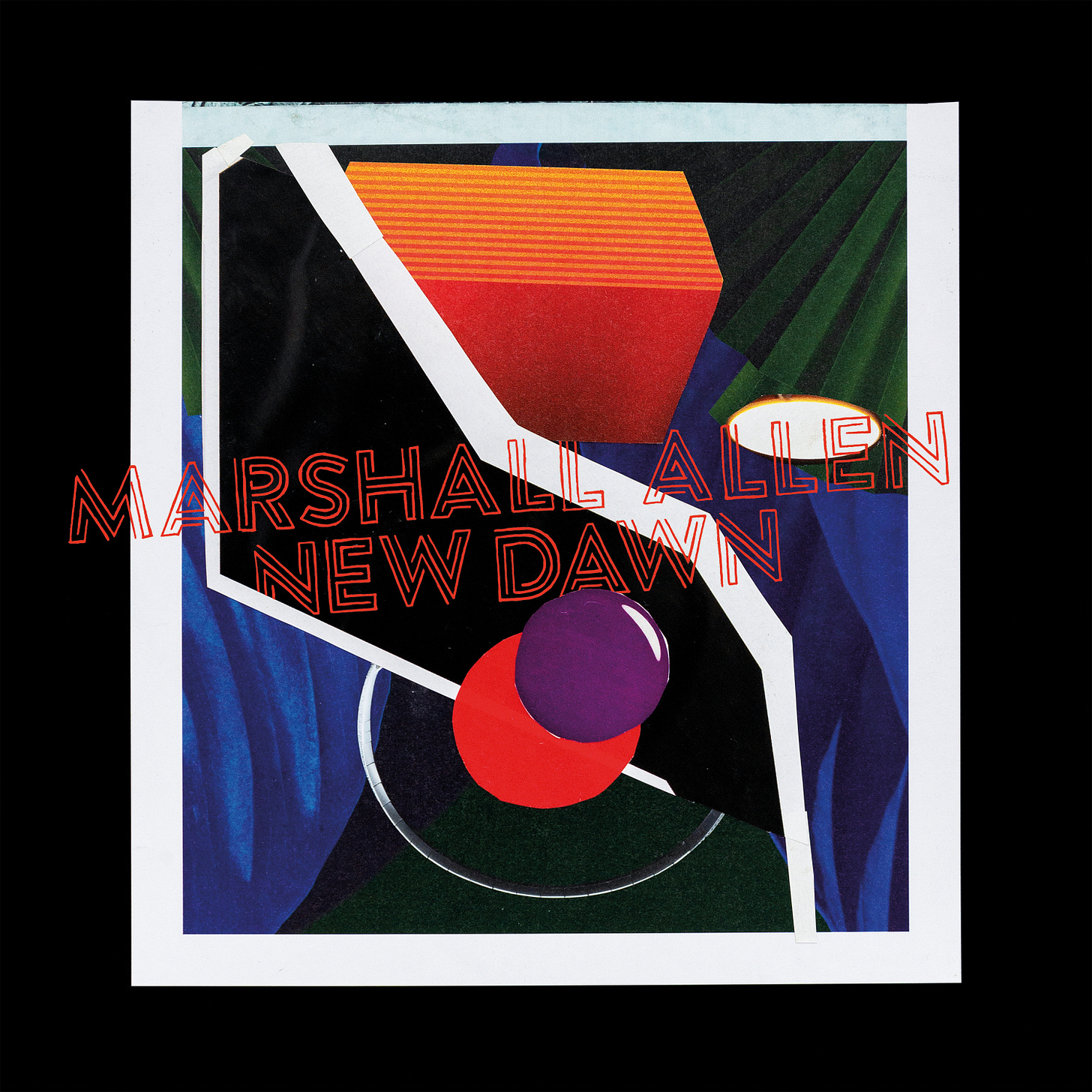

Marshall Allen, New Dawn

Before diving into the specifics of New Dawn, it is instructive to consider Marshall Allen’s long history of breaking convention under Sun Ra’s wing. He spent decades honing a sense of improvisation, unafraid to confront earthly limitations in spirited performances. Younger bandmates often described him as a guardian of the original Arkestra ethos, forever pushing them to remain open-minded. In these early years, Allen assimilated broad influences, from big band swing to outer-space improvisation, developing a signature approach in which melody and abstraction became equal partners. This debut album departs from the frenzy often associated with avant-jazz, favoring reflective pieces that feature Allen’s saxophone gently weaving through spacious arrangements. A prime example of the album’s stylistic breadth emerges as “Are You Ready,” referencing New Orleans inspirations that recall Allen’s big band roots. It roars forth with brass-laden excitement befitting a street parade. The album’s title piece includes a guest vocal appearance by Neneh Cherry, whose ethereal presence complements Allen’s warm yet futuristic EWI touches. Each selection confirms that even a century into his life, Allen remains drawn to uncharted methods and continues to trailblaze new musical possibilities. — Murffey Zavier

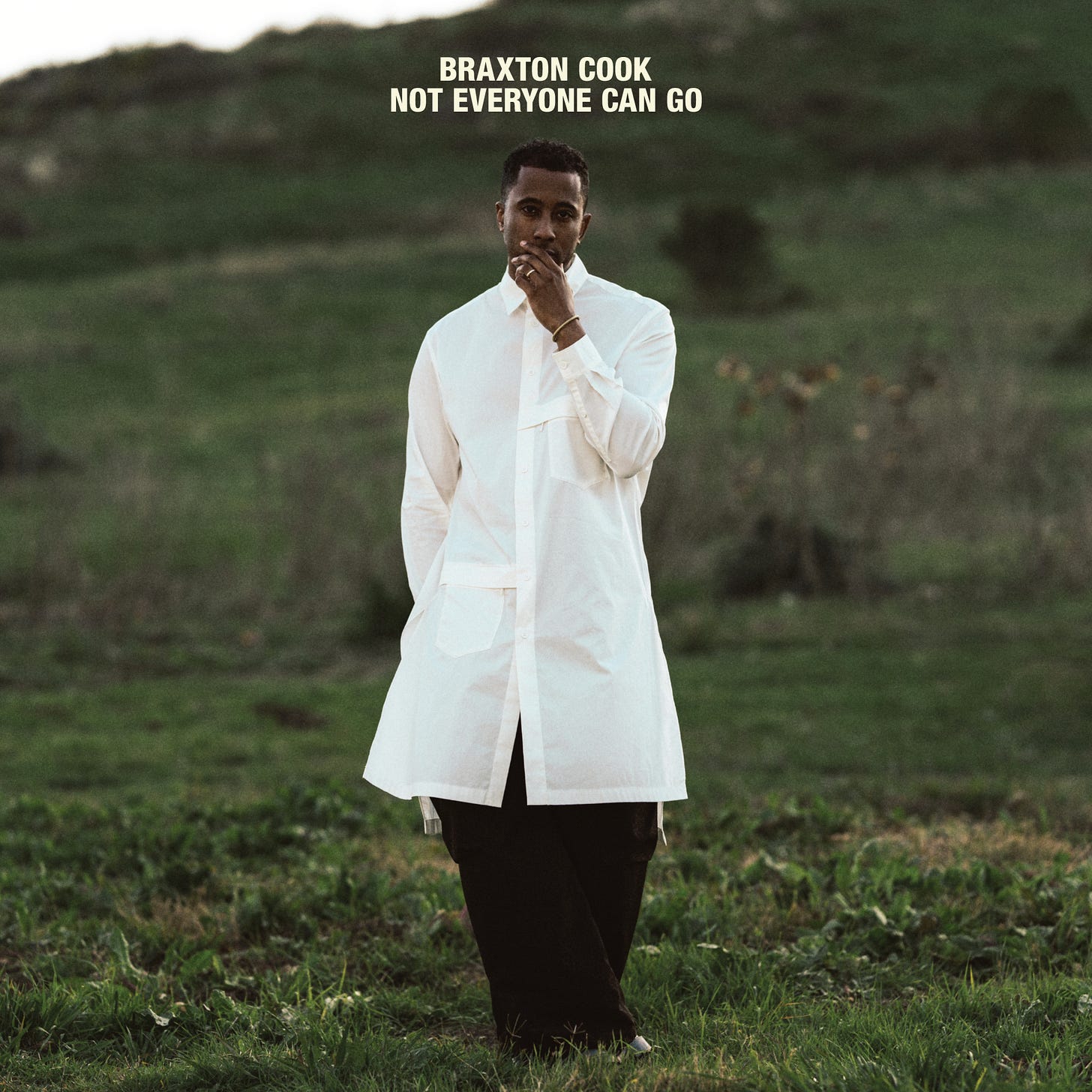

Braxton Cook, Not Everyone Can Go

Braxton Cook’s résumé runs from Georgetown to Juilliard to touring with Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, yet on Not Everyone Can Go, he brings that elite training back to personal questions about friendship, ambition, and mental health. The title track lays out his guiding principle: to reach a new stage he must let go of relationships and habits that no longer serve him. From there he writes a series of plainspoken vignettes: “Zodiac” uses astrological signs as shorthand for patterns in a relationship, “My Everything” openly asks a partner to be there without sugarcoating—“You said you’d always be there for me … my everything”—and “Harboring Feelings” admits to stockpiling resentments until a couple can name them and move on. “Weekend” shifts from confession to escapism with the invitation “Ima see ya on the weekend, I think we need a reset … just tell me where the beach is so we can get our feet wet”. Later, he uses “We’ve Come So Far” to count progress and remind himself of his mental health victories, while “BAP” includes a motivational monologue about sticking to one’s plan. As the record winds down, Cook returns to intimacy—“I Just Want You” pledges time and devotion, and “All My Life” with Marie Dahlstrom vows lifelong partnership. Throughout the project, he strikes a balance between ambition and gratitude, making room for growth by acknowledging what must be left behind. — Nehemiah

Patricia Brennan, Of the Near and Far

On Of the Near and Far, Patricia Brennan scales that curiosity up to a mid‑sized ensemble with strings, winds, and electronics, using constellations and celestial geometry as loose guides for pieces that rarely move in straight lines. Early in the record, tunes like “Antlia” and “Aquarius” unfold as patient accumulations of small rhythmic cells, marimba or vibes setting a pulse while strings and horns trace arcs around them, sometimes aligning, sometimes slipping past each other. “Andromeda” shows her rock impulse, feeding a frantic motif into distorted strings and more aggressive drumming, then letting the whole thing erupt and cool without ever losing track of the underlying design. On “Lyra” and “Aquila,” her first recorded string arrangements, you can hear her using the bowed instruments almost like sustained extensions of the mallet attacks, smearing harmonies where another writer might stack clean chords. The impression is of a composer who loves grid‑paper concepts and star charts but still trusts instinct and surprise, inviting this larger group to move between precision and wildness without losing their shared center of gravity. — Phil

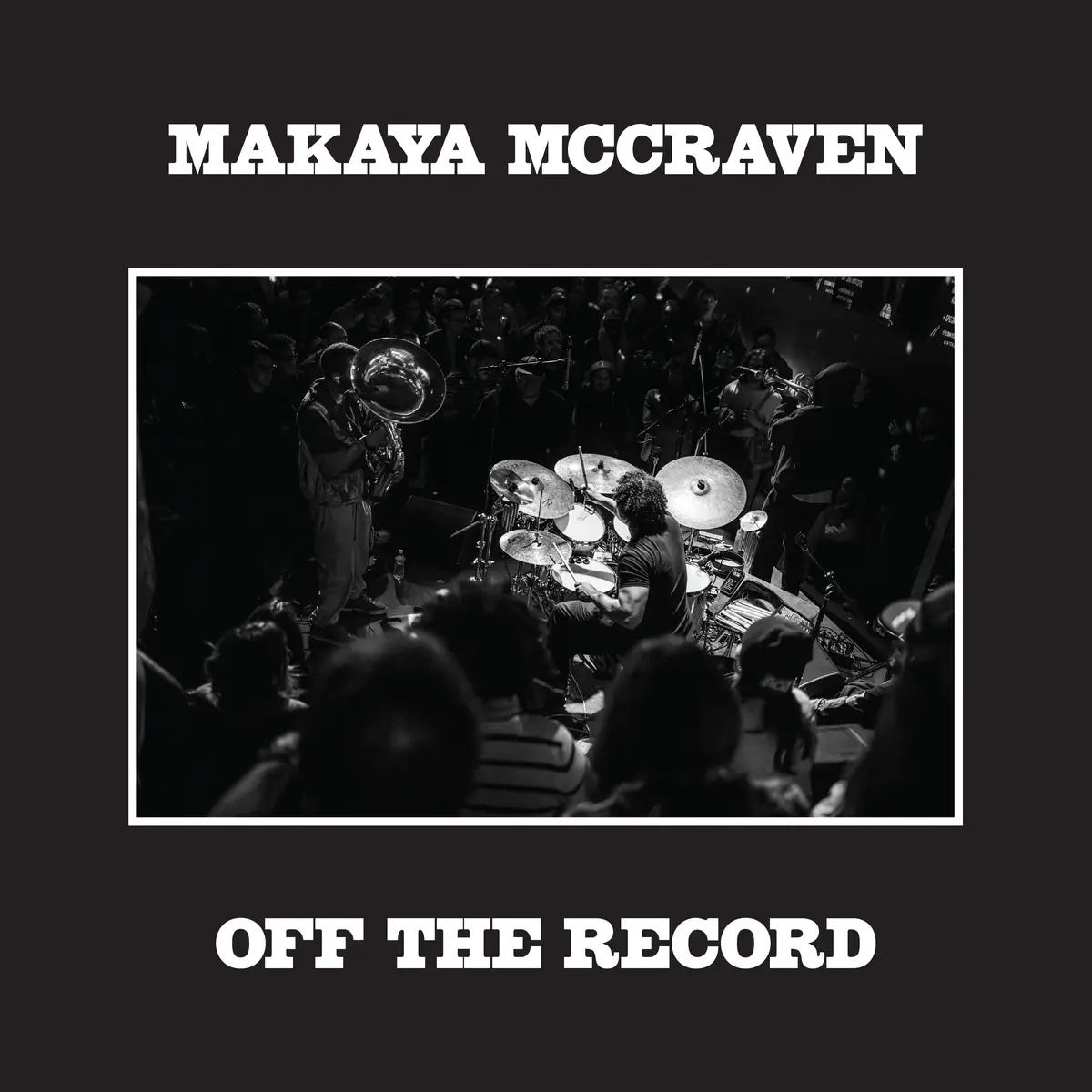

Makaya McCraven, Off the Record

On the incredible Off the Record, Makaya McCraven pulls together four chapters of that process and makes you hear how steady his obsession is, even as the textures and lineups keep changing. The material that became PopUp Shop and Hidden Out! starts with raw club energy—crowd noise, long forms, players stretching—and then gets carved into tight loops and song‑sized shapes where Jeff Parker’s guitar, Marquis Hill’s trumpet, and other voices flicker in and out like hooks. Techno Logic leans harder into low brass and dirtier electronics, tuba lines, and Ben LaMar Gay’s sounds jostling with drum patterns that nod to dance music without copying it. The People’s Mixtape feels like the most recent snapshot of his world, a more cohesive ensemble riding those same chopped‑up foundations with a little more polish and clarity. Taken together, the set reads like a behind‑the‑scenes map of how he turns open‑ended improvisation into something that lives comfortably next to beat tapes and DJ sets without giving up its live‑band spark. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Cécile McLorin Salvant, Oh Snap

Years of rigorous training, deep inquiry into jazz traditions, and a restless curiosity set Salvant up for this newest project, one that widens her instrumentation, her references, and her confidence. Over four years, she shaped these songs, starting solo sketches before bringing in her band and collaborators, so the album moves between intimacy and expansiveness. There’s marveling in language, in form, in what a voice can do when bent, stretched, when connected with unexpected textures. “I Am a Volcano” blends otherworldly vocals with electronics, while “Take This Stone” (with guest voices) leans toward folk harmony, and the cover verse of “Brick House” is deployed less as nostalgia. Arrangement choices surprise: synthetic elements, vocoder or house pulses, a cappella moments, swinging jazz runs, stark folk sounds. The voice is always centered but transformed, and the record never lets the formal experiment overshadow the emotional core. In comparison with her previous work, which already pushed boundaries, Oh Snap feels more expansive in its risk, yet grounded in craft, so the oddness feels generative. For those who follow jazz not only as a tradition but also as a renewal, this is Salvant in full motion—remaking what is possible, inviting admiration and challenge. — Harry Brown

Nate Mercereau, Josh Johnson & Carlos Niño, Openness Trio

Three improvisers walk into a room in Los Angeles with no charts, no safety net, and a shared belief that melody can be negotiated in real time. Mercereau’s guitar sometimes behaves like a pedal steel lost in space, bending notes until they cry or laugh depending on the afternoon light. Johnson’s alto and flute arrive like birds that trust the windows have been left open on purpose; he circles themes, lands, then lifts off again before the listener can decide whether they were phrases or prayers. Niño’s percussion is less time-keeper than weather system—gongs suggest distant thunder, shakers imitate wind through palms, and a lone kick drum pulses like the city breathing two blocks away. Across four long pieces, the trio practices radical listening. A single chord can linger long enough to become architecture; a sudden flurry of notes might evaporate before you can photograph it. You leave the room lighter, convinced that openness is not a posture but a practice. — Nehemiah

Jamael Dean, Oriki Duuru

Dean sat at a grand piano at 2220 Arts + Archives, with no written program, allowing a sixty-minute improvisation to flow uninterrupted; the Yoruba title translates loosely as “piano poems,” underscoring how invocation, rather than virtuoso display, guides the music. “On Green Dolphin Street” appears in phantom outline, its harmonic skeleton reharmonized into quartal voicings, while “Tin Tin Deo” rides cross-rhythms that nod to its Afro-Cuban roots without locking into clave. Originals like the two-minute “Rise & Fall” incorporate small melodic cells—sometimes just three notes—into spiraling left-hand ostinati, demonstrating Dean’s mastery of tension and release. — Murffey Zavier

Gerald Clayton, Ones & Twos

On Ones & Twos, Gerald Clayton channels a crew of improvisers into a unified force. Joel Ross’s vibraphone dances across the tracks, casting a luminous glow that reflects jazz’s golden age. Elena Pinderhughes shapes her flute lines with a voice-like quality, shifting between melancholy and uplift. Marquis Hill’s trumpet carves out bold, reflective arcs, while Kendrick Scott’s drums lock in a steady yet free rhythm. Ever the anchor, Clayton threads his piano through compositions blending modal jazz, soul, modern classical, and Afro-Latin flavors. After the studio captured their initial interplay, Kassa Overall stepped in, remixing the tracks with a producer’s ear, adding beats that pulse beneath the surface. The result shines in moments like “Sacrifice Culture,” where the ensemble’s chemistry feels alive, or “Endless Tubes,” a track that hums with collective energy. Split into sides A and B, the album mirrors a DJ’s craft, with titles like “Angels Speak” and “Lovingly” trading phrases across the divide. Ones & Twos thrives on this interplay, a record where every player’s contribution fuels a broader, breathing whole. — LeMarcus

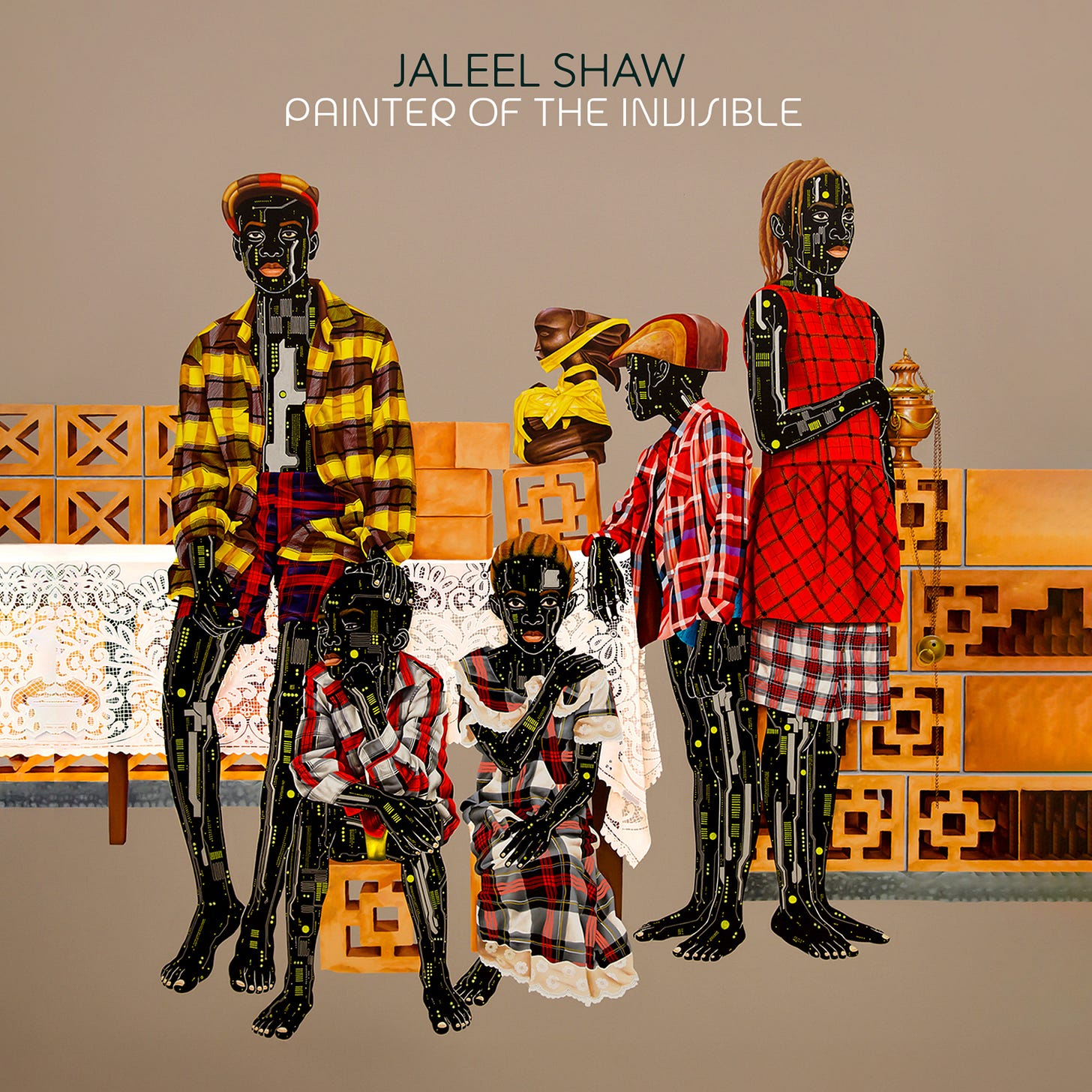

Jaleel Shaw, Painter of the Invisible

This alto player, who can burn when pushed but tends to put craft and clarity ahead of sheer volume, might help explain why so much time passed between his leader dates. After much anticipation, Painter of the Invisible arrives after more than a decade of mostly sideman work and feels like him opening up a notebook that’s been filling quietly in the background all along. After a brief prelude in “Good Morning,” pieces like “Contemplation,” “Beantown,” and “Distant Images” stretch into long, patiently developed narratives where his alto lines move from silky to rough‑edged, responding to shifts in the rhythm section rather than just skating on top. “Baldwin’s Blues” folds literary weight into a form that still swings, hinting at the author’s fire in the way phrases twist and refuse easy closure. The dedication “Tamir (For Tamir Rice)” slows the temperature without losing intensity, Shaw hanging on certain notes a little too long, letting space and slight inflections do as much work as flurries of notes. Across the record, you hear someone intent on telling full stories song by song, willing to let grooves ride and solos climb slowly instead of announcing every big idea in the first chorus. — Murffey Zavier

Don Glori, Paper Can’t Wrap Fire

Multi-instrumentalist Gordon Li assembles a rotating sextet whose horns trace Ellington-school voicings while the rhythm section locks into Eddie Palmieri-tight montunos. “Dusty Shelves” foregrounds congas and cowbell before dissolving into Fender Rhodes clusters—proof of Li’s affinity for early-‘70s CTI fusion, but the pocket remains resolutely modern, closer to Hiatus Kaiyote’s elastic swing than straight revivalism. Throughout, he leans into vocal choruses—wordless at first, then bursting into gospel call-and-response on “Black Flame”—a stylistic expansion from his previous, mostly instrumental catalog. The title track’s final two minutes stack tape-looped horns atop a drum-and-bass rhythm, suggesting that even Don Glori’s most soulful gestures refuse complacency. — Randy

Milena Casado, Reflection of Another Self

Spanish trumpeter Milena Casado’s debut is less a set of tunes than a suite of interior monologues rendered in sound. Co-produced with Terri Lyne Carrington, the record cross-fades brushed-snare swing, open-horn motifs, and harp glissandi into vapor-hiss electronics and sampled family conversations, mapping trauma and self-reclamation onto a dreamlike jazz-scape. “O.C.T.” tilts a muted trumpet solo over Val Jeanty’s turntable textures, letting fractured beat-snippets glitch beneath harmonic minor progressions that evoke late-‘60s Miles while sounding unmistakably 2025. Three brief “Introspection” interludes splice whispered Spanish questions through reversed cymbals, creating breathing room before the quartet surges back with modal burners including “Resilience,” where Lex Korten’s piano clusters chase Casado’s growling upper register until both resolve on a luminous chord the composer calls “miracle major.” The closing featuring Meshell Ndegeocello’s bass harmonics and Brandee Younger’s cascading arpeggios lands like morning sun after a night of reckoning—proof that the album’s title isn’t rhetorical but a sonic ritual of becoming. — Imani Raven

Alfa Mist, Roulette

On his sixth studio album, Roulette, Alfa Mist marries his signature fusion with a bold near-future concept: a world where reincarnation is treated as data and the past lives of individuals reshape society. The London-based pianist, producer, and MC builds expansive arrangements that drift between soulful keys, groove-laden beats, and atmospheric psychedelia, layering each piece as if it’s a chapter in a speculative saga. Throughout, he interrogates memory, identity, and justice: what happens when your former lives become witness, evidence, or burden? Alfa Mist’s compositions grow more detailed and more exacting, and he turns the wheel until various mixes of jazz, hip-hop, and speculative fiction fuse into one unbroken motion. Across the album’s cool expanse, Alfa tests how far jazz can stretch before it becomes its own philosophy: not nostalgia, but recursion, where groove and thought occupy the same orbit. Even at its most meticulous, his music resists perfection. Its precision vibrates with doubt, as if each production is aware that to return is never to repeat. — Harry Brown

Linda May Han Oh, Ambrose Akinmusire & Tyshawn Sorey, Strange Heavens

They have all led dense, carefully constructed bands on their own, but when they strip down to a trio, the focus shifts to the raw edges where their instincts collide. moves between fragile quiet and sudden surges, bass, trumpet, and drums constantly renegotiating who’s carrying melody, harmony, or rhythm from moment to moment. On “Portal,” a simple figure from the bass might be enough to set the whole shape, Akinmusire entering with a line that hovers at the edge of speech while Sorey brushes and taps around the beat rather than sitting directly on it. At other points, they lean into more combustible energy, the trumpet moving into cries and smears, the drums cracking open the time, and the bass digging into dark, insistent ostinatos that keep things from floating away. None of it feels like a freestyle session. You sense three composers using improvisation as a way to test ideas about density, texture, and silence in real time. The emotional weight comes less from big themes than from how exposed they’re willing to sound, leaving small imperfections and hesitations in place instead of sanding everything down. — Reginald Marcel

Natural Information Society & Bitchin Bajas, Totality

Putting them in the same room almost guarantees a slow burn. Joshua Abrams’ Natural Information Society and Bitchin Bajas have each spent years chasing long‑form pieces where small shifts in pattern feel as important as chord changes. They lean into that shared patience, building side‑long tracks as environments that listeners can move around in rather than problems to be solved. The opening title piece starts in a hazy blend of sustained keyboards, reeds, and overtones from Abrams’ guimbri, then gradually tightens into a hypnotic seven‑beat groove where Mikel Patrick Avery’s drumming and the interlocking lines suggest motorik rock and North African trance at once. “Always 9 Seconds Away” slows things back down into a thicker, doom‑jazz fog, pulses stretching out while synths and harmonium‑like tones swell and recede. Shorter cuts like “Nothing Does Not Show” and “Clock No Clock” find a bit more focus, riding steady rhythmic figures that let you hear how precisely the two groups fit together, one side often supplying pure tone and the other more attack and grit. The record works less by surprise than by accumulation, rewarding anyone willing to sit inside its subtle shifts and feel how the combined band gently bends your sense of time. — Nehemiah

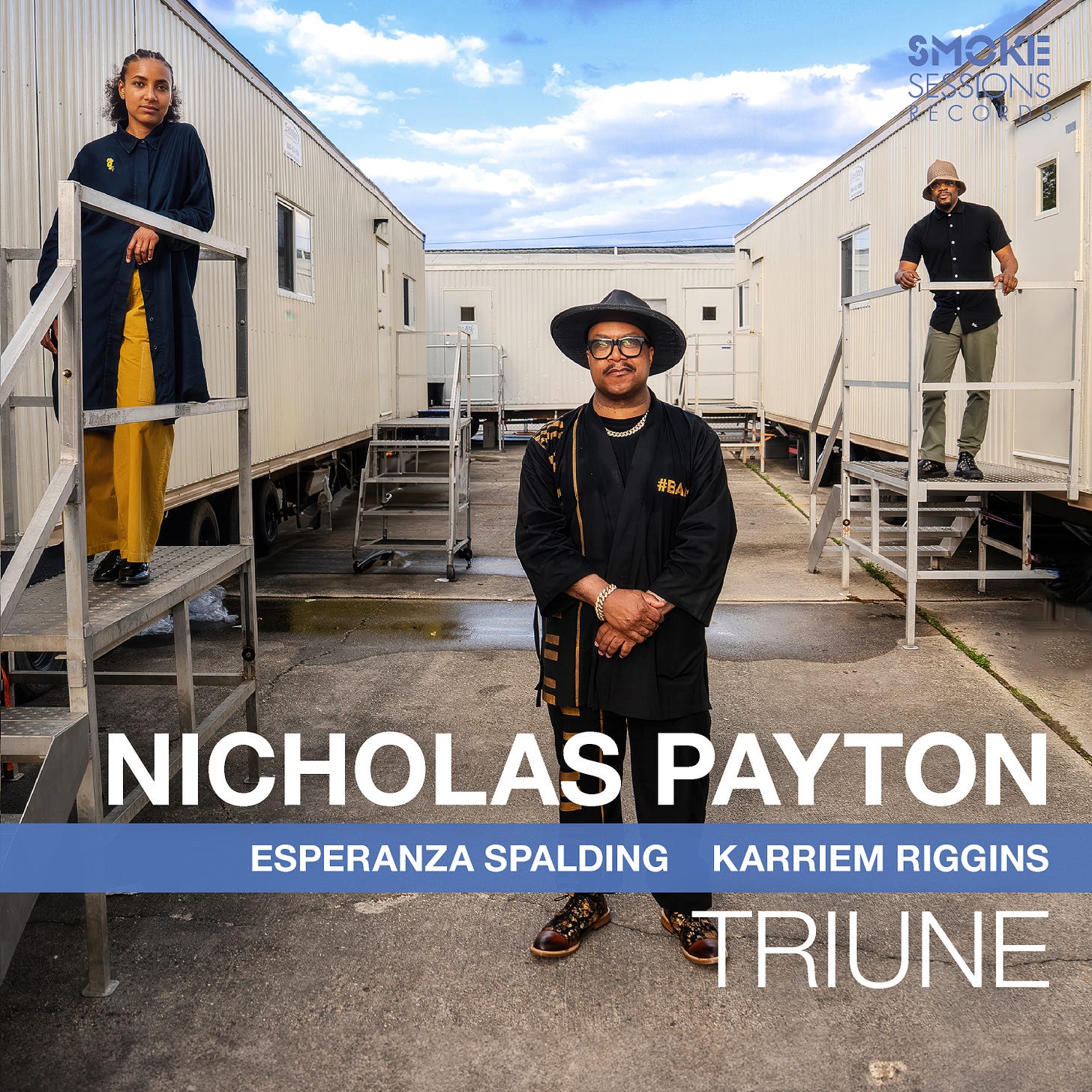

Nicholas Payton, Triune

A dream team. Nicholas Payton, Esperanza Spalding, and Karriem Riggins are all used to steering their own projects, yet when they play together, the energy feels less like a star summit and more like three friends finishing each other’s sentences. On “Unconditional Love,” Payton’s trumpet and keys, Spalding’s singing bass lines, and Riggins’ dry, springy drum sound lock into a pocket that feels relaxed and alert at the same time, leaving plenty of space for her voice to slide between melody and commentary. A tune like “Ultraviolet” or “Gold Dust Black Magic” might start from a simple vamp or keyboard figure and slowly thicken into something funkier or more harmonically slippery, with small rhythmic nudges from Riggins or a shift in Spalding’s phrasing changing the whole feel. “Jazz Is a Four‑Letter Word” and “#bamisforthechildren” foreground talk about lineage and community without turning didactic, folding those ideas into chants, bass ostinatos, and little production touches. Throughout, you get the sense of three musicians who could easily dominate a room choosing instead to practice restraint, trusting that the deepest statements come from how carefully they listen to one another. Triune is built on that sense of equality, the trio leaning on groove, song form, and open improvisation in roughly equal measure while trying to move as a single organism. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Kokoroko, Tuff Times Never Last

London’s brass-heavy family returns with eleven pieces that feel like open windows in July, letting the city’s humid breath drift through. Sheila Maurice-Grey’s trumpet and Anoushka Nanguy’s trombone circle each other like cousins trading jokes at a barbecue, while Yohan Kebede’s Rhodes chords smolder like charcoal left glowing after the food is gone. “Never Lost” begins with a wordless lullaby that sounds like sunlight on wet pavement, and from there the record wanders through memories. “Sweetie” stirs Afrobeat polyrhythms into the mix until the horns burst into exclamations too joyful to stay pent up. Lulu appears on “Idea 5 (Call My Name)” and stretches the groove into late-night neo-soul, her voice sliding across the brass like fingertips on bare shoulders. The miracle is how nothing feels rushed on Tuff Times Never Last. Even when the band edges toward melancholy—“My Father in Heaven” glows with gospel ache—the pulse remains steady, a reminder that sorrow and celebration can share the same heartbeat. Play it at dusk with the windows open, and the street becomes part of the arrangement. — Imani Raven

Niia, V

Niia finds herself in the space between cool and disorder, creating her own world of experimental pop with the element of the unexpected live performances of jazz-trained musicians. Throughout the album, she follows the lines of self-harm, illusion, awareness, and the transience of self-love. V is a bright contemplation of lust, heartache, and release, the most significant declaration she has ever made after years of crafting sound between retro-chic and danger. The tension and opposition between restraint and surrender not only characterize the music itself but the imagery too; the cover displays Niia with a fork of a heretic (an extreme in the Middle Ages when anyone who used it could have their mouth shut) turned outside-in to become a kind of symbol of rebellion and powerlessness. — LeMarcus

Terri Lyne Carrington & Christie Dashiell, We Insist 2025!

With Terri Lyne Carrington, she has been steadily using her bands to question who gets centered in jazz history, rewriting canons on the bandstand rather than just in the classroom. Here, she chooses one of the most charged texts she could touch. We Insist 2025! revisits and reimagines Max Roach’s We Insist! Freedom Now Suite with Christie Dashiell as a central narrative voice, turning pieces like “Driva’man,” “Freedom Day,” and “All Africa” into present‑tense dispatches rather than museum pieces. Carrington’s arrangements keep key rhythmic and melodic kernels intact while opening up fresh spaces for reharmonization, spoken passages, and collective improvisation, so an anthem you might think you know bristles with new accents and countermelodies suddenly. Dashiell moves easily between straight singing, more speech‑like delivery, and wordless textures, sometimes carrying explicit lyrics about labor, violence, and resistance, other times acting as another instrument inside the ensemble. The multi‑part “Triptych: Resolve/Resist/Reimagine” makes the suite’s original scream section into something that acknowledges ongoing trauma without sensationalizing it, using shifts in texture and dynamic to convey strain and determination. In later movements like “Tears for Johannesburg” and the new interlude “Dear Abbey,” what comes across is not reverence for a classic so much as an insistence that its questions about freedom and responsibility still belong to this moment. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Emma-Jean Thackray, Weirdo

Thackray’s second full-length channels grief, neurodivergence and P-Funk devotion into a kaleidoscopic self-portrait. Credited on 123 roles, from trumpet to art direction, she wields maximalist jazz orchestration one moment and grunge-distorted guitars the next. “Wanna Die” stages multiple Thackrays in a mock late-‘90s TV skit, masking lyrics about suicidal ideation beneath slapstick. Deeper cuts like “Black Hole” merge Clinton-style clavinet squelch with Leeds brass-band refrains, affirming her mantra of dancing through despair. Written after the sudden 2023 death of her long-term partner, the album documents a crawl from Zelda-induced stasis back to music-driven purpose, closing with the gospel-soul lift of “Thank You for the Day.” It’s less a genre piece than a survival diary sung in cosmic-jazz dialect. — Nehemiah

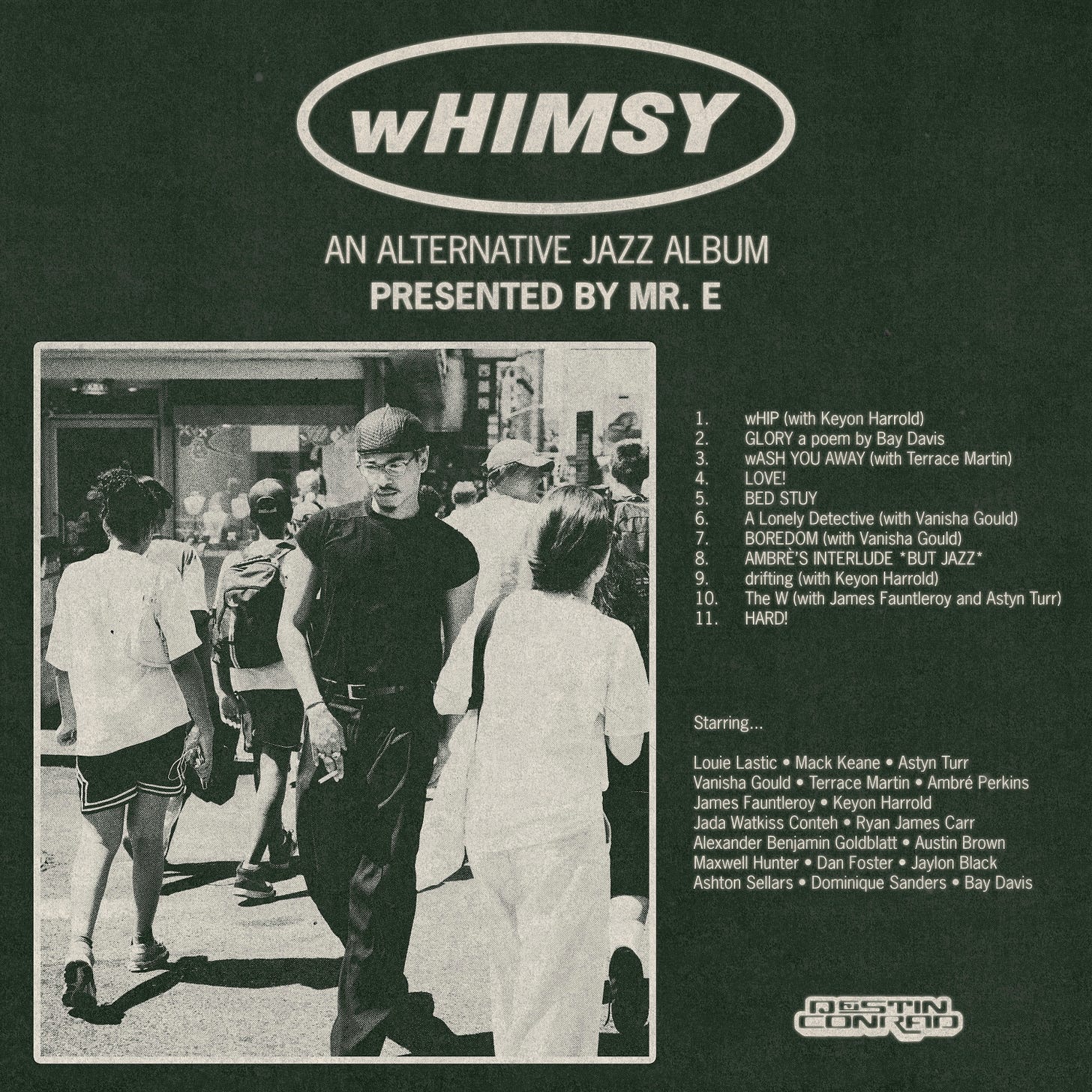

Destin Conrad, wHIMSY

As an R&B writer for Kehlani and others, Destin Conrad became known for streamlined hooks with conversational vignettes. Coming off of Love On Digital, wHIMSY abandons any hint of formula and uses a spare jazz backdrop to spotlight the intensity of his words. The album’s centrepiece, “wASH U AWAY,” opens with the unguarded line “I left your crib this morning and I smell you on my neck,” a sensory marker that makes the narrator’s internal argument about whether to cling or let go feel lived rather than imagined. Elsewhere he uses micro‑scenes to anchor his themes: “wHIP” reduces a relationship to the drive back from a night out; “BED STUY” shrinks a city down to a single neighbourhood; and the spoken‑word “GLORY” by Bay Davis reframes surrender as something safe (“Wanna show you how safe surrender can be when it’s holy … And my God, how selfish we’d be to keep all this glory to ourselves”). Even the lighter songs carry sharp edges: the plea on “LOVE!” (“Love, can we talk? … Is it really hard? Wanna make it mine”) and the deadpan complaint in “BOREDOM” (“You’re so far and you’re so boring”) refuse to generalise. By stripping away production flair and leaning on everyday diction, Conrad delivers a jazz‑infused project where each song feels like an extended note to someone specific, and the album’s whimsy lies in how unsentimental his reflections are. — Jamila W.

Christian McBride, Without Forever Ado, Vol. 1

With Without Further Ado, Vol. 1, McBride leans into that side of his personality, a playground for his restless curiosity, folding in funk, R&B, and whatever else he’s been soaking up on the road. He stacks the seventeen‑piece band with guests and vocal features while still leaving plenty of room for sharp ensemble writing. The opener, “Murder by Numbers,” brings Sting and Andy Summers into a setting where McBride’s bass and the brass section thicken the song’s original unease, turning it into something closer to a noir miniature than a pop throwback. Later, Jeffrey Osborne steps up on “Back in Love Again,” riding a groove‑first arrangement that lets the rhythm section snap while the horns punch accents and respond to his phrases like an extra choir. Samara Joy and other singers appear across the program, each used less as a star cameo than as part of a larger story about how this band can shift from swinging charts to more contemporary feels without changing its core identity. Threaded through is McBride’s sense of humor and drama, especially in longer suites where he builds from compact riffs to thick, almost orchestral climaxes and then back down to intimate moments. It’s the sound of a leader who trusts his writing and his musicians enough to make a big ensemble feel flexible, current, and genuinely social. — Phil

Thank you for this smorgasbord of gems and recommendations!

Extraordinary. Thank you ever so much for this… just brilliant :)