The 50 Best R&B Albums of 2025

While pain, joy, and everything in between are found in these songs, rising stars, veterans, and legends shared stages across 2025. Even amid uncertainty, they leaned on the story to keep hope alive.

If you look at 2025 R&B with a mainstream lens of the success of Kehlani, Leon Thomas, and Mariah the Scientist with their hit singles, sure, there’s not much going on, but the genre was so much more than that. This year became a sanctuary for stories we all carry but rarely share out loud. From heartbreak and healing to found family and self-discovery, the voices on this year’s standout records refused to stay behind closed doors. They spoke boldly about vulnerability—not as a weakness, but as a bridge between listener and singer—and invited us into rooms filled with laughter, tears, and the quiet moment before dawn.

You could hear it in narratives of survival, confessionals of desire, and odes to personal growth—songs that challenged us to lean in rather than glance away. Across cities, bedrooms, and live-room sessions, performers traded pretense for nuance, trading big statements for careful questions. Veterans dusted off old instincts and found fresh urgency, while newcomers (outside of what you see on random editorial Spotify playlists) arrived with hearts wide open and pens sharper than ever. In the list that follows, we celebrate the albums that dared to ask, to feel, and to transform everyday experience into real music. It may not match the higher highs of last year, but it reminded us why this genre of music matters: it speaks directly to the heart, in all its complexity and contradiction.

Welcome to the best of R&B this year (plus, our playlist to go along with it).

SAULT, 10

SAULT quietly releases banger after banger, and 10 extends the collective’s numerological breadcrumb trail while pivoting from the widescreen orchestration of Acts of Faith toward something intimate and sun-dappled. The ten-song suite (its tracks titled only in initials) binds gospel harmony, Laurel-Canyon folk chords, and feather-light Afro-beat percussion into hymns about rebuilding spiritual muscle after grief. Cleo Sol’s voice floats over brushed drums and rubbery P-bass supplied by Pino Palladino, while Michael Kiwanuka and Dave Okumu slip in ghost-guitar lines that keep the record moving like a procession rather than a set list. Recorded largely live to tape, the music never bubbles past a low simmer, yet subtle modulations—hand-clap breaks, wordless choir swells, a stray synth-brass stab—keep forward motion constant. The band’s trademark opacity remains, but the metadata confirms the April date and the reappearance of SAULT’s core ensemble, solidifying 10 as another piece in the group’s ongoing gospel-soul continuum. — Phil

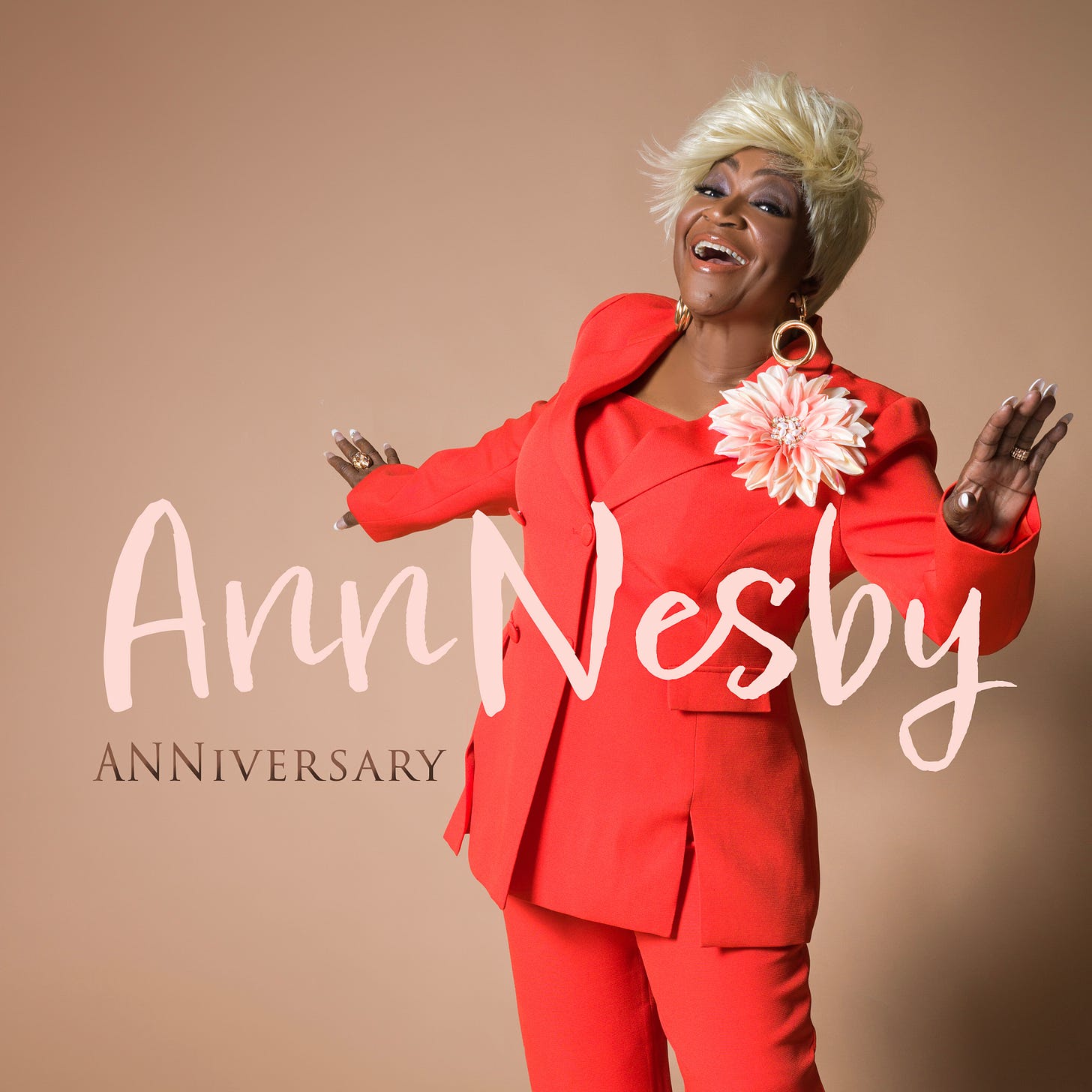

Ann Nesby, ANNiversary

After more than ten years without a full-length studio release, Ann Nesby—her voice a cornerstone of soul music’s rich history—presents ANNiversary, her eighth album. From her days with Sounds of Blackness to this latest chapter, Nesby shapes grown-folk R&B into a medium that examines love, self-worth, and emotional accountability with unflinching honesty. The album’s ten tracks unfold as a study in human connection, with “Missing You” capturing the ache of absence, “Who” turning inward to question identity, and “My Man,” featuring writing credits from R.L. Huggar, asserting a confident claim to devotion. Brian “B-Flat” Cook, her longtime production collaborator, builds a musical foundation that amplifies Nesby’s vocal strength, blending classic soul textures with a contemporary edge. ANNiversary reaffirms Nesby’s status as a GRAMMY-winning artist whose authenticity continues to define the genre’s evolution. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Peyton, Au

Peyton arrived in the mid-2010s with a flair for dreamy alt-soul; she began releasing full-length projects while still in her early twenties, yet often spoke about feeling constrained by the expectations of youth. Her sophomore album Auarrives after a four‑year stretch that included PSA and scattered collaborations, and she describes it as the moment she let go of self‑consciousness and fully embraced who she is as an artist. She worked closely with Shafiq Husayn and Om’Mas Keith, members of the LA collective Sa‑Ra Creative Partners, and credits them with creating a space in which she could take risks and blend lo‑fi textures with psychedelic funk. She’s wrestling with betrayal, confusion, and disappointment, yet the mood never turns sour—Au is a kind of pact with the self: even when the world tries to dull your shine, you stay luminous. Her second LP leans into spacious R&B, moments of slow burn, and dreamy instrumental touches, with guest features (Didda Joe, Brian Alexander Morgan) adding color but never distracting from Peyton’s core tone. Peyton has painted a portrait of an artist who has grown comfortable enough with herself to let her guard down and let the songs breathe. — Jill Wanassa

Galactic & Irma Thomas, Audience With the Queen

Irma Thomas proves her voice remains a commanding force at 83 on Audience With the Queen. Her career, launched with a hit in 1959, has made her one of the city’s most iconic figures, a GRAMMY-winning artist whose influence stretches across decades and genres. On this album, Thomas channels that strength into a range of expressions—love ballads, political declarations, and songs that lift the spirit with purpose. Take “How Glad I Am,” a cover of Nancy Wilson’s 1964 classic. She infuses it with a gospel depth that nods to her church roots, turning a familiar tune into something distinctly her own. Then there’s “Over You,” a pulsing track where Thomas wrestles with the aftermath of a failed romance, her vocals cutting through Galactic’s tight, funky arrangement. Galactic, a mainstay in New Orleans for 30 years, brings their signature mix of blues, jazz, and that unmistakable local funk, providing a modern foundation that complements Thomas’s classic soul sound. This album arrives at a moment when the music world often mourns greats after they’re gone. Instead, Audience With the Queendemands recognition for Thomas now, a living legend whose work continues to shape the Crescent City’s musical identity. Her collaboration with Galactic underscores the importance of honoring artists in their time, ensuring their contributions resonate while they can still hear the applause. — Imani Raven

Dijon, Baby

After the hard-won leap of Absolutely, Dijon returns with a second full-length built to pressure test what comes next. He writes from the life he’s been building, partner and new father in the house, and he bends the record toward that pressure with a jumpy, collage-minded approach that treats memory and domestic noise as usable parts of the kit. Songs pivot on sudden cutaways, voices pitch and splinter, and the drums lurch from human swing to clipped fragments that feel sampled even when they are played, a method he sharpened with Mk.gee and BJ Burton and kept flexible with Andrew Sarlo and Henry Kwapis. The effect is a steady argument for intuition over symmetry. Hooks arrive from the side, a shout becoming a refrain, a breath turning into a cue. When he asks, “Is it all just patterns packed inside,” the question doubles as a design note, because repetition here is never quite repetition, and the lyric keeps the music honest about what love and panic can do to form. A track like “Another Baby!” moves like a quickening thought, synth stabs and vocal yelps ricocheting without losing the thread of devotion, while “My Man” wears bright R&B vowels over scuffed tape edges so the tenderness has grain to it. Even when the room gets loud, the writing stays intimate, naming ordinary rituals and doubts with the clipped attention of someone catching ideas between feedings. The album’s core is that lived-in speed, and a tight circle of collaborators, a comfort with messy takes, and a belief that a family’s daily weather can power a pop record without sanding it down. — Tai Lawson

Reuben James, Big People Music

After years of supplying graceful piano runs for singers such as Sam Smith and learning the grind of tour life, British jazz wunderkind Reuben James decided his own voice deserved center stage. On Big People Music, he uses that decision as a responsibility. The album pairs that resolve with warm, conversational narratives: “You’re Mine,” a duet with Emeli Sandé, imagines lovers clinging to one another even as the world burns around them, while “Show Me You’re Love” pleads for reassurance from a partner whose silence feels like betrayal. James balances introspection with broader spiritual excursions. “Deep Inside” borrows Afrobeat inflections to describe a search for ancestral wisdom, and throughout he circles back to gratitude, even having horns reprise earlier themes to remind listeners that every hustle needs moments of reflection. His lyrics are simple yet earnest, trading technical showmanship for frank admissions of fear and commitment, and by the end, the pianist comes across not as a virtuoso flashing his chops but as a songwriter using music to process adulthood. — Jamila W.

Durand Bernarr, Bloom

Raised by two musician parents and homeschooled in a creative household, Durand Bernarr has always preferred communal music-making to solitary practice, and last year, he reached a turning point. The Cleveland-born R&B artist had built serious momentum with his En Route EP, a project that earned him a fresh wave of fans and a 2025 Grammy nomination. Bloom is a clear shift from his usual approach, born out of necessity and seeking fresh input. Bernarr leaned on collaborators like GAWD, featured on the upbeat “Flounce,” and b.kae, who co-wrote the lead single “Impact.” Songwriter Timothy Bloom and friend Bella Rose rounded out the crew by adding background vocals. The result feels like a tribute to all kinds of bonds: romantic, platonic, creative. The album’s strengths shine in its variety. On the shimmering 1990s throwback “No Business,” he chastizes himself for loving someone who doesn’t deserve it, admitting, “I ain’t got no business loving somebody else the way that I love you.” It contrasts sharply with “Unspoken,” a standout ballad that ranks among 2025’s best tracks. Even the playful duet “That!” with T‑Pain and the deeply personal closer “Home Alone” serve Bernarr’s larger theme—he sings about his parents’ unconditional love and finds solace in his own space, gratefully recalling how they “never once felt condemned, didn’t throw me away.” Bernarr’s choice to pivot, pulling in outside voices while keeping his core sound intact, shows an artist adapting under pressure. Bloom doesn’t reinvent R&B, but it proves Bernarr can stretch his limits and deliver something worth hearing. — Jamila W.

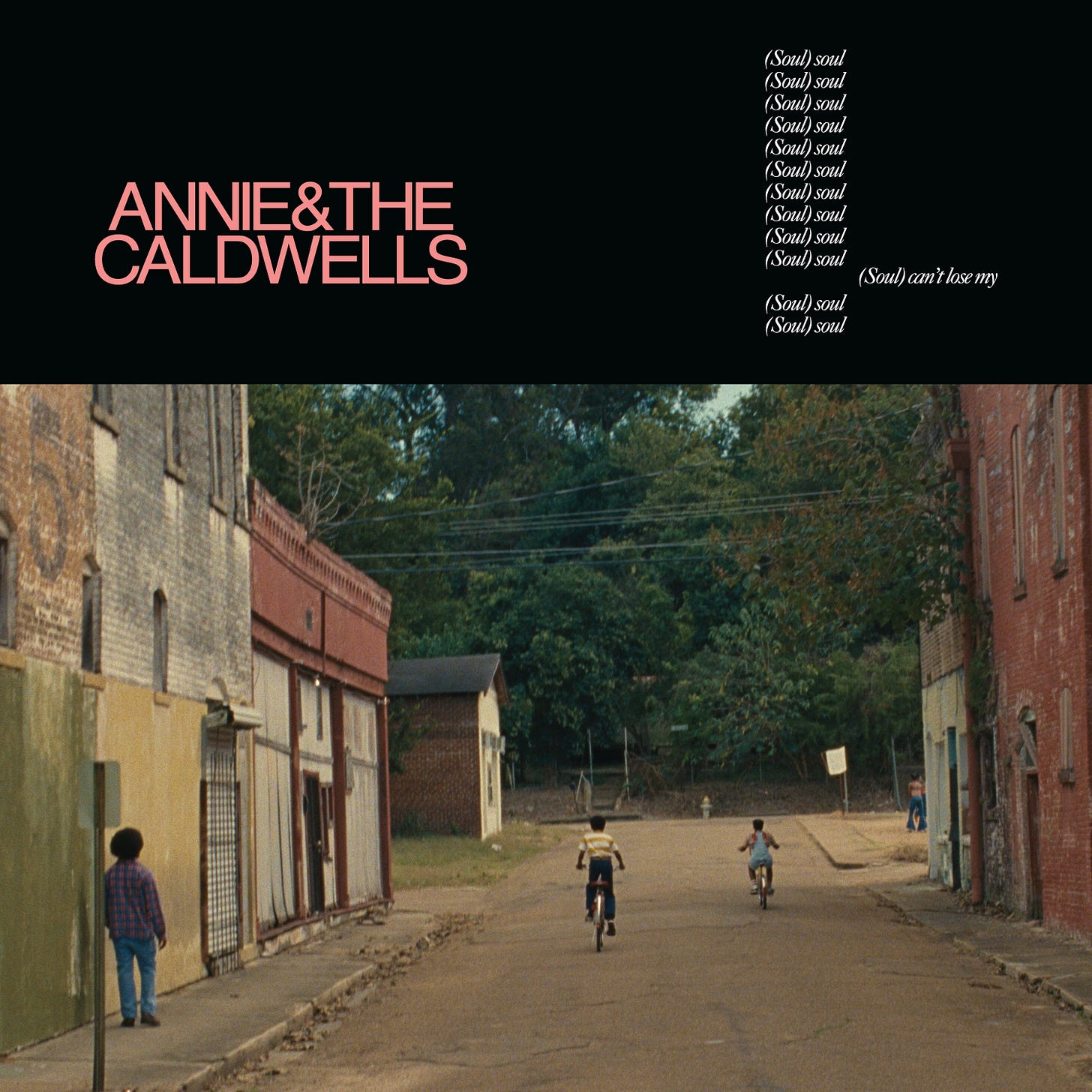

Annie & The Caldwells, Can’t Lose My (Soul)

The story behind Can’t Lose My (Soul) is almost as compelling as the record itself. In the early 1970s, Annie Caldwell and her siblings released a single as the Staples Jr Singers. Decades later, crate‑diggers resurrected that 45 and sparked a revival, leading to a modern recording by Annie with her daughters that sounds like a family band reclaiming its own history. The title track stretches ten minutes, pulling you through the murk of soul, not some organ you can pin down, but the root of the genre’s name. Sinkane builds it tight and fills it with layers of soundtracks propping each other up, with every voice fighting for the front. It’s no timid gospel redo. That spirit carries into “Don’t You Hear Me Calling,” where call‑and‑response vocals enact the urgency of prayer, and “Dear Lord,” whose liquid bassline and funk groove offer a plea for guidance without succumbing to despair. On “I’m Going to Rise,” the group draws on southern soul, promising to get up and keep going despite grief, while disco‑tinted numbers such as “I Made It” and “Wrong” recall Chaka Khan and celebrate survival. The album hits like a first swing, rethinking 2025’s take on the sacred with a gut-punch drama. Byrne’s eye for quality holds—audio nuts will geek out, but the weight sticks. Experience shows, and the struggle is now paying off. — Imani Raven

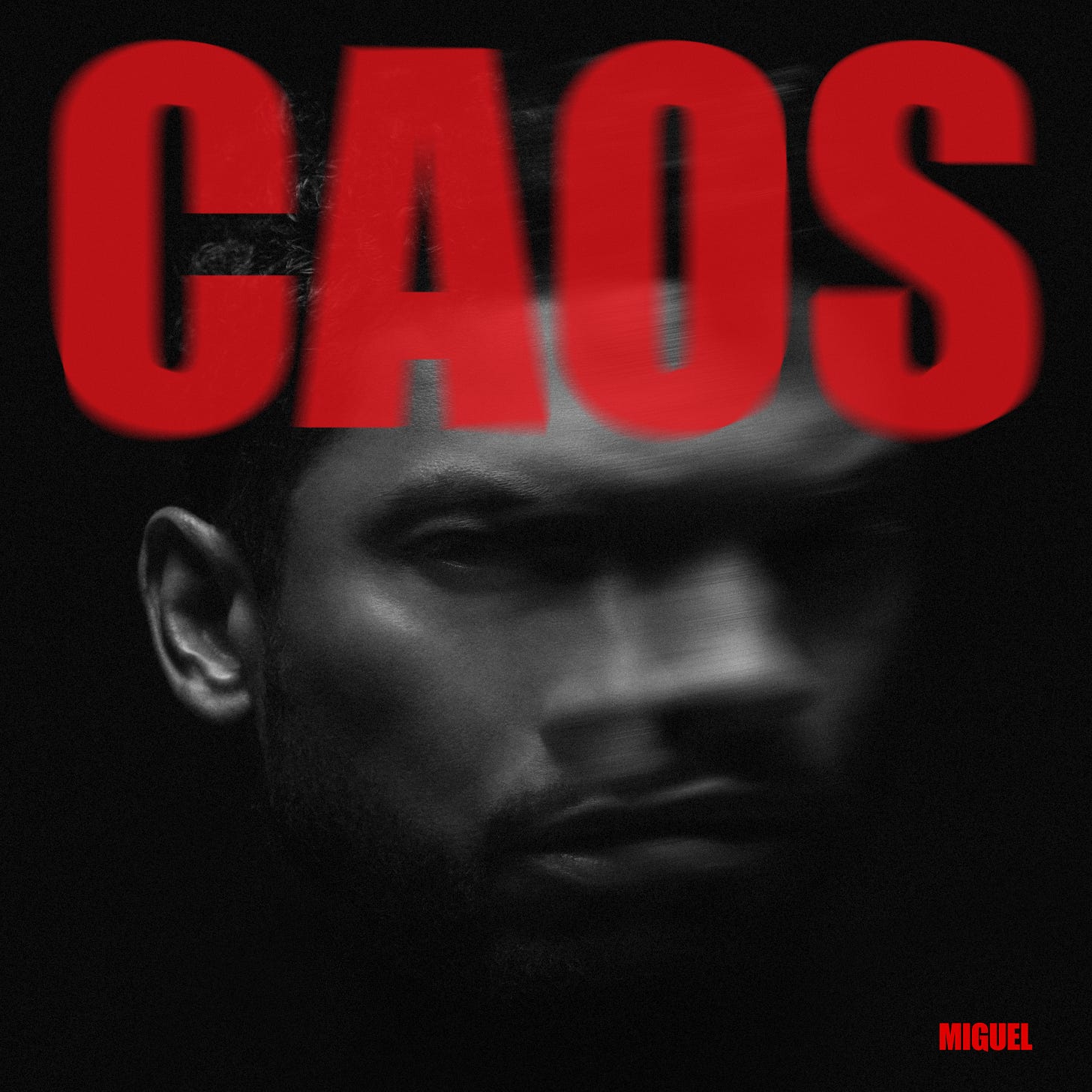

Miguel, CAOS

After War & Leisure’s party and political-fueled haze in 2017, Miguel Jontel Pimentel vanished into fatherhood and film scores that sharpened his ear for emotional undercurrents, making CAOS his rawest return in eight years. After spending the late twenties crafting kaleidoscopic R&B visions on albums such as Kaleidoscope Dream that fused falsetto runs with guitar riffs drawn from his San Fernando Valley garage jams, earning Grammy nods for turning bedroom confessions into arena anthems, this fifth album creates a bilingual storm of songs that wrestles love’s wreckage into defiant rebirth through verses that bleed Spanish introspection and English urgency. The titular track sets the torrent loose with opening lines that equate life’s chill to growth’s rain—“La vida es fría, el frío es dolor, el dolor, crecimiento/Y cada semilla que crece, ve llover como siempre”—Miguel’s delivery turning personal storms into universal cycles where loss waters what’s next. “New Martyrs (Ride 4 U)” flips sacrifice into solidarity, lyrics vowing “I’ll ride for you through the fire” amid tales of lovers martyred by doubt, the bridge trading verses on shared wounds that forge unbreakable rides. “Triggered” unspools emotional landmines with “One word and I’m triggered, back in the fight,” verses that map how old fights resurface in new skins, and spill out, owning the volatility as fuel for honest collisions that clear the air. CAOS follows the progression of Miguel—from performer to fighter—and the music that reinvents the chaos of heartbreak into choruses that throb with the imperative rhythm of life. — Phil

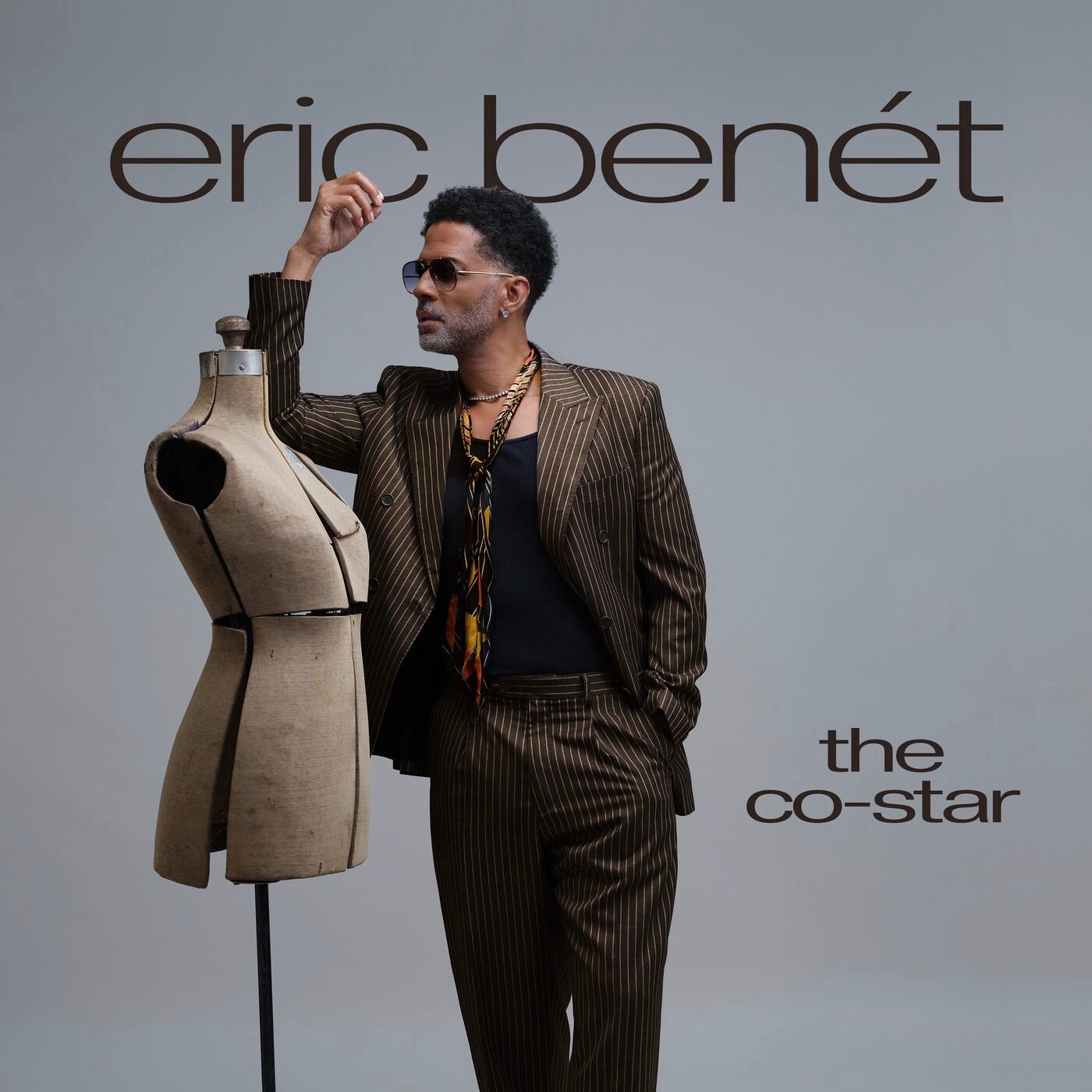

Eric Benét, The Co-Star

Eric Benét pivots from front-stage crooner to skilled partner on The Co-Star into a conversation rather than a showcase, starting with Ari Lennox’s sharp warning on “Gaslight”: “Could’ve been beautiful, but you’re cold and egotistical.” Benét has spent decades perfecting the art of the romantic slow jam, yet curated a suite of all-woman-led duets inspired by Keri Hilson’s suggestion to name the project after his supporting role. India Arie answers with gentle reassurance on “Must Be Love,” and Corinne Bailey Rae lifts “Fly Away” with light guitar. On “Remember Love,” Benét and Alex Isley revisit a past relationship through overlapping melodies and minimal percussion, letting silence underline the unspoken emotions. Live drums, Rhodes keys, and soft horns supply an easy pop-soul cushion that never crowds the singers. Lyrics keep circling trust, apology, and mutual care, so the duets feel like practiced listening sessions. SalDoce slips a samba pattern under “Too Soon,” where patience and regret share space. Judith Hill and Melanie Fiona steer “Southern Pride” and “Me & Mine” toward family themes. Spanish track “Eres Mi Vida,” sung with Pia Toscano, extends the record’s inclusive spirit without novelty. Benét sounds most engaged when partners push back or co-sign his lines, proving the album’s title accurate. — Tabia N. Mullings

Terrace Martin & Kenyon Dixon, Come As You Are

Within a framework of supple Rhodes chords and barely there drum loops, Terrace Martin and Kenyon Dixon explore self-regard as a communal practice. Dixon speaks plainly about love and vulnerability, offering insight into emotional surrender. Martin complements that with understated yet expressive jazz touches—Robert Glasper and Keyon Harrold add soft flourishes that nod to LA’s rich musical heritage. Rather than spell out gospel influences, the pair fold call-and-response backing lines into slow-bloom arrangements that feel lived-in. Martin keeps his horn cameos sparse so Dixon’s tenor can press forward with plain-spoken reminders to “love yourself” and “keep your circle tight.” Those phrases may read simple on paper, yet the singers treat them as working lessons, revisiting them over subtly shifting keys. When Rapsody drops into “WeMaj,” her measured verse about trusted friendships widens the album’s moral compass without breaking its hush. Keyboards and bass stay in dialogue, moving just enough to suggest forward motion while leaving space for breath. Together, they prove modern R&B can speak softly and still cut deep when craft serves purpose rather than ego. — Phil

Isaia Huron, Concubania

Raised in a South Carolina church and sharpened as a drummer, Isaia Huron moved to Nashville to build as a writer and producer. In the wake of a run of EPs and a loosies tape that hinted at range without settling the stakes, he makes a first full statement with a debut album that’s way more than just ‘solid.’ In recent interviews, he’s tied the idea to the mess of desire and faith, drawing a clear line between biblical cautionary tales and the way people move now, which gives the album a moral center without turning it into a sermon. That path explains the way Concubania is, where his writing stops auditioning and starts holding itself to account. On “I Chose You,” he writes from inside commitment rather than around it, describing the pull of impulse and the stubborn work of staying, and the verse-to-verse shifts feel like someone arguing with his habits in real time. “See Right Through Me,” a duet with Kehlani, pushes that tension further by turning confession into a two-way test of trust, as the exchanges read like carefully worded texts finally said out loud, and the pockets of silence between lines make the promises carry weight. He studies the language of uncertainty head-on—“I Think So?” and “Unsure” give indecision shape, not by hedging but by naming what doubt actually sounds like when you’re trying to choose better. “List Crawler” is a story song about curiosity and surveillance, brisk and specific enough to feel pulled from a real thread you wish you hadn’t scrolled, while “Thotful” turns defensiveness into a small character sketch. Across the set, Huron’s voice stays conversational and direct. He builds a record you can follow like a candid journal, where the details do the heavy lifting. — Harry Brown

Lady Wray, Cover Girl

Lady Wray has since built a catalogue steeped in church harmonies and old‑school rhythm‑and‑blues. Cover Girl finds her easing into that role with confidence. After the introspective Piece of Me, this record is more playful and uplifting, blending 60s soul, 70s disco, 90s hip-hop, and gospel influences into one celebratory mix. The organ‑driven “My Best Step” uses hand‑claps and church keys to reaffirm loyalty and perseverance, and the album’s messages of empowerment are apparent in songs such as “Where Could I Be” and “Hard Times,” which invoke faith and resolve amid hardship. The title track revisits a childhood nickname as Wray sings about losing herself to please others and the slow process of rediscovering her own beauty. Throughout the album, she reminds women that they are worth more than society tells them, as on the retro‑soul groove “Higher,” and she ends with “Calm,” a gospel‑tinged prayer that casts burdens aside and looks toward brighter days. Lady Wray delivers an album that balances upbeat anthems with honest reflections on love and self-acceptance, drawing from her church roots and decades of experience. — Imani Raven

Ledisi, The Crown

Ledisi just gets it. From her early days in New Orleans clubs to her Grammy‑winning turn as an independent soul singer, she has always balanced technical mastery with church‑born conviction, but still feels unappreciated. Spanning 40 crisp minutes, The Crown works like a soul-philosophy class: each lesson interlaces New Orleans brass flourishes, Bay Area funk bass, and choir-loft call-and-response to examine self-worth. Two pre-release singles frame the arc: “Love You Too,” a mid-tempo groove anchored by rising church-organ swells, outlines unconditional devotion, while “BLKWMN” deploys marching-band snares and Hammond stabs to crown Black womanhood as the album’s sovereign theme. On “Heaven,” she acknowledges her flaws, confessing that she sometimes wants to tell someone off but resolves instead to show grace, singing that she’d rather extend love until she can’t any longer. The production team, mostly long-time collaborator Rex Rideout, with guests like Camper, keeps arrangements uncluttered so Ledisi’s elastic melisma can leap from jazz scatting to gospel belt. Ledisi has long used her voice to uplift, but here her writing feels particularly direct. Her twelfth studio LP highlights her shift from love-song specialist to elder raconteur, addressing faith, politics, and ancestral pride in a single breath. — Imani Raven

Jenevieve, Crysalis

With Division and the slow-bloom of “Baby Powder,” it helped established Jenevieve as a singer who could bend retro touchstones without getting stuck in nostalgia, and the four-year step to Crysalis shows a more deliberate pen working with Elijah Gabor as executive producer to shape a humid, detail-forward R&B record where the rhythm section does quiet labor and the voice does the directing; the mission statement comes from her own notes about protecting energy and trusting instinct, which you can hear in how “Haiku” compresses confession into tight lines and stacked harmonies, how “Head Over Heels” rides a supple bass figure while slipping a Tom Browne “Charisma” sample into the pocket, how “Hvn High” lifts the tempo without sacrificing intimacy and moves like a night-drive scene in its Maya Table–directed clip, and how the title track threads resolve through a warm, analog-leaning palette, with backing parts kept simple so ad-libs can carry mood and the writing favors direct address over ornament, and by the time you pass through “Missing Persons” or “Enter the Void” you can hear the larger arc she described, a cocoon-to-clarity movement built less on spectacle than on control of tone and phrasing. — Imani Raven

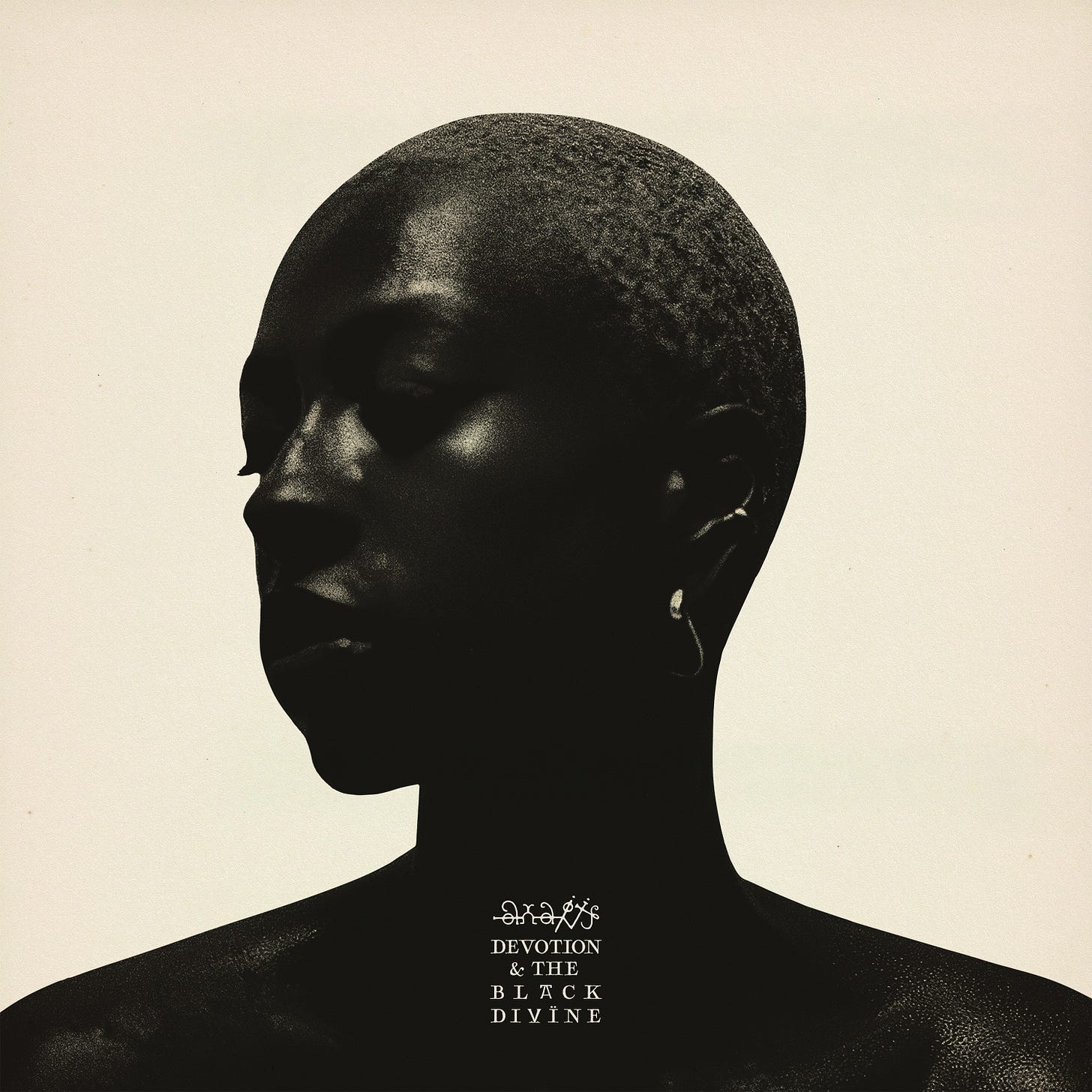

anaiis, Devotion & the Black Divine

anaiis writes from what she calls a collective consciousness, letting the album serve as a conversation between herself and the world. Recorded live to tape at London’s 5dB Studios, Devotion & the Black Divine grew out of her experiences as a new mother and her search for acceptance. The songs lean into uncertainty and grace, capturing the messiness of being human while holding on to a still center. On “Moonlight,” she sings gently over swirling chords, contemplating how hope can persist in darkness. The slow, sensual single “Deus Deus” heralded the record with its sultry soul reggae groove, hinting at the album’s spiritual core; its repeated gratitude expresses a personal prayer without ever becoming didactic. She moves between spoken‑word cadences and melismatic runs, reflecting on the weight of motherhood and the freedom that comes from surrendering control. Although the arrangements shift from sparse ballads to experimental R&B, the through‑line is her willingness to place every emotion at the core. — Ameenah Laquita

Your Grandparents, The Dial

On their latest project, Los Angeles trio use the image of a telephone as both a literal device and a metaphorical gateway. The set opens with the title piece, a stuttering break-beat and woozy Rhodes that bleeds directly into “All Dem Times,” where rumbling sub-bass underlines stacked harmony lines reminiscent of late-‘90s L.A. neo-soul sessions. Mid-sequence, “Tea Lounge/Blossom” parades in two movements: first a brittle drum-machine shuffle, then a flute-laced psychedelic bridge featuring singer Iyana that recalls Shuggie Otis’s liquid guitar phrasing. The trio’s rapper–crooner interplay peaks on “Hypnotized,” trading sing-song cadences with Belgian duo blackwave. over a clavinet riff that could have spun out of George Clinton’s vault, while “Be Cool” channels classic funk to remind listeners to stay composed when confronted with chaos. Closer “Down” rides a chopped-and-screwed chant toward silence, completing a cycle that feels like hanging up the cosmic receiver. They refine that blend into a lyrical meditation on time and presence that never feels contrived. — Reginald Marcel

Yaya Bey, Do It Afraid

Yaya Bey opens with a mantra of courage: “If you want to be brave, first you gotta be afraid,” and she lives by it across pastoral instrumentals that mix acid jazz, trip-hop, reggae, and soca. She moves between intimate confessions and buoyant grooves. The Caribbean pulse of “Merlot and Grigio,” featuring her Barbadian collaborator, showcases her ease in marrying American soul with diasporic pulses. She addresses emotional labor and misogynoir with upfront candor while never sacrificing the warmth of her voice. The arc is of trudging through fear toward clarity and self-acceptance. She skips between swagger and reflection but keeps it all grounded in a patient groove. Instead of chasing a glossy hook, she leans into conversational cadences that turn everyday grievance into melody. On “End of the World,” muted horns from Butcher Brown bloom behind her voice, framing apocalypse talk as block-party small talk. Elsewhere, “Real Yearners Unite” pares instrumentation to finger snaps, allowing the singer to confess that craving tenderness can feel defiant. By keeping production minimal and language direct, she turns personal risk into a shareable blueprint for survival. — Jamila W.

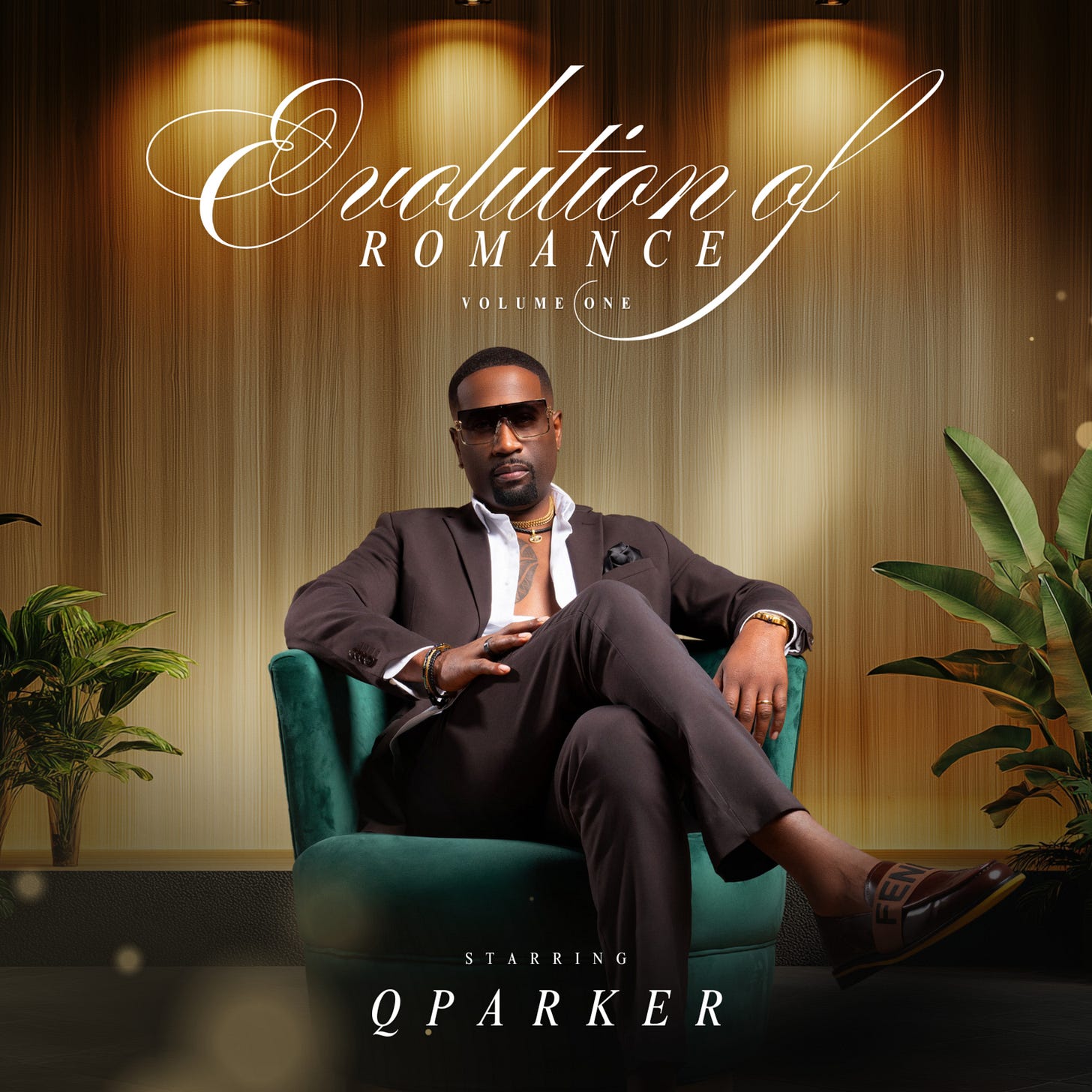

Q Parker, Evolution of Romance, Volume One

R&B’s greatest practitioners understand that romance is documented in how Black men navigate vulnerability in a culture that demands their stoicism. As a founding member of 112, Quinnes “Q” Parker is the mastermind and, with the group’s harmonies, became a radio staple through classics like “Only You,” “Cupid,” “It’s Over Now,” and the Grammy-nominated “Peaches & Cream.” But where 112’s group harmonies created collective romantic expression, Parker’s solo work demands something more personal. His 2012 debut, The MANual, established his solo identity as a vocalist embracing transparency and growth, and thirteen years later, he returns with a mission to reclaim territory he believes contemporary R&B has abandoned. The first volume of Evolution of Romancereturns to true romance, courtship, and emotional intimacy. Parker dubbing himself the “Romance Dealer” to fill what he identifies as a crucial void. “BEG,” produced by Blac Elvis, its acronym standing for Bringing Endless Gratitude rather than desperation. “Keep on Lovin’” featuring Rico Love and Dondria flips The Deele’s “Two Occasions,” a nostalgic gesture that reveals Parker’s understanding that romance requires historical memory—you can’t innovate intimacy without acknowledging its lineage. “fff.” embraces being a provider while requesting only three things in return: feed me, be intimate with me, be a fan of me, frank language delivered with grown-man directness rather than youthful bravado. — Imani Raven

Durand Jones & The Indications, Flowers

From late-night Chicago writing sessions, Durand Jones & The Indications return with a body of work that treats grown-up intimacy as dance-floor fuel. The brief intro “Flowers” leads into “Paradise,” where Aaron Frazer’s falsetto glides over an easy bass line reminiscent of early-‘80s quiet-storm staples. Durand’s fuller tone on “Really Wanna Be With You” provides contrast, turning lyrical pleading into confident assertion. Strings lift the chorus without tipping into nostalgia, signalling the group’s intent to honor predecessors while sidestepping retro cosplay. Shared vocals dominate, a choice that underscores the album’s emphasis on collective resilience rather than individual virtuosity. Many takes were captured live, preserving tiny imperfections that make the grooves human enough to invite repeated spins. “Been So Long” articulates reunion joy with the line “it’s good to be back together,” summing the album’s narrative in everyday language. By balancing disco shimmer with straight-talk sentiment, the band proves maturity and fun can still share the same dance floor. — Imani Raven

Mourning [A] BLKstar, Flowers for the Living

The Cleveland collective—known for welding gospel harmonies, distorted bass, and free‑form poetry—uses this album around the idea of giving loved ones their flowers while they can still smell them. As Mourning [A] BLKstar blurred the line between lament and celebration, “Stop Lion 2” fuses distorted bass drone with a field-recorded Baptist shout, interrupted by a spoken-word salvo from Lee Bains that sounds like Gil Scott-Heron channeled through a post-punk megaphone, and you have the title track where vocalist RA sings about holding himself accountable while promising to motivate his community. Elsewhere, “Letter to a Nervous System” layers tape echo on dour trumpet lines, evoking the echo-chamber anxiety of the album’s title. Yet hope persists: closer “88 pt.” hinges on a modal, Major-7th guitar vamp that brightens each chorus, suggesting blossoms pushing through concrete. Multiple lead vocalists trade lines like communal testimony, transforming grief into collective propulsion. “Can We?” flips an older groove into a funkier plea, asking if the band can indeed be funky and letting the answer unfold through wry interplay. — Brandon O’Sullivan

The Amours, Girls Will Be Girls

Washington, D.C. sisters Jakiya Ayanna and Shaina Aisha grew from choir blend to tour-tested vocalists before stepping to the front under their own name. The album treats harmony as narrative stance, not garnish, so you hear two points of view find agreement in real time; when “That One Ex” snaps into the taunting line “I don’t mean to brag, but I be in my bag all 25/8,” the bite works as their blend stays tidy even as the text grins. “Clarity” uses the opposite energy, a steadier vow about naming needs, and Camper’s direction locks the tempo to the lyric’s plain talk so the refrain hits like a decision rather than a plea. Their pain favors small specifics—how you set terms, how you tell the truth when it costs you—and the production mostly moves out of the way, with bridges that lift just enough to make the final chorus feel like an answer. Years spent on PJ Morton’s stage trained them to project intimacy; that muscle shows up here in tight vocal stacks that act like underlines instead of fireworks. The net effect is a debut that reads with conversational detail and harmonies that argue and agree with a sister’s precision. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Elmiene, Heat the Streets

The ambition and voice of Elmiene have been growing. Following a string of EPs that teased intimacy and promise, Heat the Streets delivers. It’s the story of love, loss, longing, and the pain of being unable to connect when distance or silence gets in the way. The project details his disorientation after a breakup, introducing the themes of vulnerability and longing that run throughout it. Rather than chasing fleeting trends, he highlights timeless values and moves from tender ballads to funk‑driven grooves. His gentle tenor and poetic lyrics transform each song into an intimate confession, and the interludes offer a welcome respite. There’s a confessional quality, wherein moments of heartbreak (“Useless (Without You)”) but also celebration (“Sunny”), a sense that vulnerability is your only weapon. A mixtape like this refuses to gloss over grief, which remains raw yet rich. When someone steps beyond hype and creates works you come back to for comfort or catharsis, Elmiene feels like the promise realized. — Jamila W.

keiyaA, Hooke’s Law

On her turbulent second album Hooke’s Law, keiyaA doesn’t just susurrate her frustrations—she unleashes them. The record confronts living in the gaze of the industry, the contradictions of self-care culture, and the weight of expectation as a Black queer woman (“an album about the journey of self-love, from an angle that isn’t all affirmations and capitalistic self-care… It’s more of a cycle, a spiral”). Adding her strengths as a well-rounded music producer, she welds jazz, club-music heat, and R&B tenderness into jagged, slippery grooves—Auto-Tune one moment, horn squalls the next—so heartbreak and anger sit beside seduction and swagger. What’s on the line is an album that doesn’t simply process pain, it confronts it head-on—and still moves you to dance. — Tai Lawson

Flwr Chyld, InsydeOut

Flwr Chyld has spent years shaping a lane where R&B leans on discipline rather than mood. He came up in Atlanta’s ecosystem of arranger-first musicians, the ones who build their sound brick by brick until something coherent emerges. His early projects showed flashes of that control, but InsydeOut is the first time he drags all the loose ideas into the same room. The album catches him trying to square tenderness, distance, and self-protection without letting the production turn into soft focus. What gives the record its spine is how he handles contrast. He’ll set a warm chord bed, then cut it with clipped percussion or a bass tone that refuses to sink into the background. It’s a way of admitting that the relationships he’s writing about sit on uneven ground. Songs move the same way conversations do when someone is half-trying and half-pulling back. “EmptyBaggage” shows the template clearly—Kent Jamz walks through the messiness of wanting someone while knowing he keeps breaking his own patterns, and Flwr Chyld keeps the beat tight so every line lands without cushioning. — Esther Blake

Ayoni, ISOLA

Ayoni has always been the kind of artist who writes with the clarity of someone searching for her own reflection in real time. Building up her repertoire of loosies and featured on Noname’s Sundial, ISOLA is where that process transforms into a cohesive body of work. The title carries dual weight because it’s a nod to her Barbadian roots, an island identity that shapes her worldview, and it’s also an exploration of isolation, the way distance can magnify pain and foster transformation. She tells stories of heartbreak, anger, renewal, and self-discovery—songs that read like journal entries but are polished into resonant anthems. Tracks such as “It Is What It Is” and “Bitter in Love” walk directly into the grief of betrayal without posturing, while “Trace of Your Love” and “Vision” open the lens wider, asking what it means to hold on when love dissolves. She executive-produced the album herself, and that sense of authorship shows in the way motifs recur and melodies return as lessons. It’s a declaration of presence, proof that Ayoni’s pen and voice are strong enough to build universes without overstatement. It arrives as a debut that sounds like a marker planted in the ground, pointing toward even larger visions still to come. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Samm Henshaw, It Could Be Worse

Recorded with a live band and collaborators like executive producer Josh Grant and vocalist Ogi, It Could Be Worse runs through twelve tracks built on drums, piano, bass, and guitar instead of dense programming, leaving his gravelly tenor and stacked background parts space to crack, joke, and lean into faith without sanding the feeling down. Samm Henshaw is an artist who has one foot in church and one in a South London venue, raised on gospel records and mainstream pop, and trying to write songs that can hold gratitude, doubt, and everyday mess in the same breath. After his 2022 debut Untidy Soul and a mini‑album about burnout, he spent the last few years moving through family losses and his first major heartbreak, eventually landing on a phrase his mum kept repeating, “it could be worse,” as a way to file that whole period and as the title for a second album he’s described as the rawest he’s ever been. “Float,” the fourth song and one of the only tracks he’s shared digitally, wraps a careful piano line and head‑nodding groove around a plea not to drift too far from someone he still cares about, written just after the breakup and sung from that middle ground where you’ve accepted it’s over but haven’t moved on yet. A little further in, “Get Back” reaches for earlier days that felt easier and asks how to return to that mindset without lying about how heavy things are now, while “Hair Down” rides a looser, almost playful rhythm as he tells listeners to let go for a minute and, as he puts it, let Jesus handle the steering when life feels out of control. “Don’t Give It Up,” “Wait Forever,” “Don’t Break My Heart” and “Tangerine” circle the same knot from different angles—when to hold on, when to stop trying, how to keep a sense of humour when setbacks stack up. — Kendra Vale

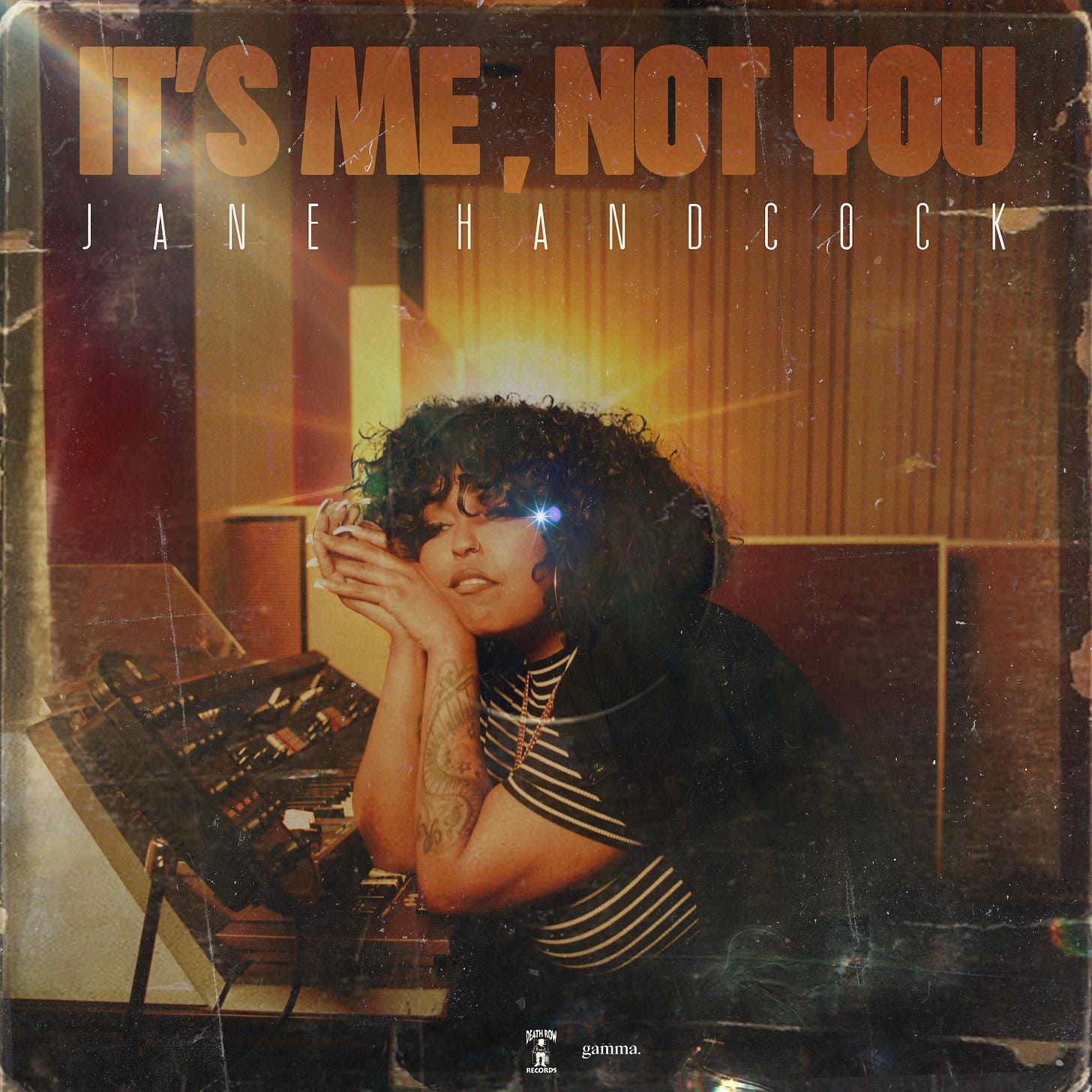

Jane Handcock, It’s Me, Not You

Oakland’s Jane opens the door in fuzzy house slippers, pours you something brown and strong, then spends forty-seven minutes explaining why every failed romance was actually syllabus material. She glides from dusty boom-bap to shimmering west-coast funk without ever losing the living-room intimacy of two friends talking past midnight. “Use Me” rides a Soopafly loop that knocks like an aged Impala trunk while Jane’s alto flips between sung confession and half-rapped punch lines, admitting she liked being needed more than she liked the man who needed her. “Sorry” adds splashes of electric guitar that sting like slammed doors, and by the time BJ the Chicago Kid gets a chance to slide into “You,” the album has become a duet cycle—lovers trading accountability like a joint they both know is almost out. Anderson .Paak brings his rubber-limbed drums to “Stare at Me” and the groove struts straight out of a downtown loft party; “Stingy” coos possessiveness over finger-snaps so laid-back they’re practically horizontal. Yet the quietest moments cut deepest—on “Niraj,” Jane sings over Charlie Bereal’s lone guitar, addressing the kind of beautiful disaster everyone swears off until the next text lights up the screen. On It’s Me, Not You, she’s no longer blaming exes; she’s watching new love rise like heat shimmer over summer asphalt and deciding, cautiously, to walk toward it. — Jamila W.

NAO, Jupiter

After taking time off to recover from chronic fatigue and parenthood, East London singer NAO returns with Jupiter, a record steeped in optimism and spiritual growth. She builds the album as a companion to her breakthrough Saturn, noting that this time she wanted to focus on hope, joy, and expansion. Her writing refuses to wallow, turning it into something brighter and more assured. She doesn’t lean on one genre or mood but shifts between them. The album opens with “Wildflowers,” a song that carries a calm, free-flowing energy, setting a steady tone across the record. NAO plays with styles here, blending a sharp guitar solo in “Elevate” with the tight, tasty beats of “We All Win.” The mid‑tempo “30 Something” finds her shedding the baggage of her twenties by confessing, “I’ve been holding on to shit that don’t belong to who I am as a 30 something.” The title track uses cosmic metaphors to argue for collective healing; she repeats “We all win/When light gets in” and pleads, “Reality don’t bring me down to Earth Leave me up in orbit where my feelings won’t get hurt.” She easily moves between sounds, pulling from past decades while keeping things current. — Tai Lawson

Reggie Becton, The Last Great American Summer

Reggie Becton steps into sunlit territory here, long known for moonlit confessionals, heartbreak laments, and the “sad-boy” R&B undercurrents. This album marks a coming into oneself as much as coming out of sorrow, and you can feel both past and present in every note. The Last Great American Summer frames identity, age, growth, mortality, Freedom over Fear, and Passion (“fire”) as necessary fuel. His struggle is with what it means to reach 30, what it entails to live by one’s own terms, and what it means to be authentic rather than cutting corners. “Die Young” isn’t about early death, but about choosing urgency over complacency. “Purple Rain OG” invokes legacy, homage, and nostalgia even as it pushes forward. The album refashions his sound, and there are duets (Tiara Thomas on “Simple”) that add tenderness, as well as features (D Smoke on “Fake”) that bring a bruising edge. Despite the cinematic texture, the music avoids overcoating. It keeps rough edges, so the presence remains natural. A more rooted sense of purpose can be detected in this collection than in Becton’s earlier works. As R&B evolves, nuance can sometimes be lost, but The Last Great American Summer retains nuance while expanding. Despite its comfort and warmth, this album also feels like stepping out into daylight you weren’t expecting. — Jamila W.

Johnny Burgos & Jeremy Page, A Long Short Story

These two gifted individuals never fail to make a great pairing. Johnny Burgos spent years navigating brand endorsements and touring with his band, Bridge City Hustle, before connecting with veteran soul producer Jeremy Page, whose credits include CZARFACE, Kendra Morris, and MF DOOM. Their 2024 collaboration (All I Ever Wonder) established their chemistry through retro-soul techniques, but A Long Short Story, their second full-length, arrives as something unexpected—not simply a homage but a transmutation, where Chicano soul and Motown aesthetics collide with contemporary club energy and prog-rap experimentation. “Under Your Window” captures love and urban heartbreak, tempo changing as horns blare in, Burgos hitting notes with sniper-like precision. The title track fills with strings while “Sidelines” bounces with bright flamboyance, striking swashes of purple surrounding them—the specter of Prince hovering without explicit mimicry. Page’s production adapts to Burgos’s range, his influences surfacing not as quotation but as DNA recombined into something that honors lineage while refusing museum treatment. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Destin Conrad, Love On Digital

In an era of swipe‑culture and selfie streams, Love On Digital finds Tampa-born crooner Destin Conrad mining Y2K chat-room nostalgia—AIM pings, flip-phone chirps, Neptunes-esque synth-plucks—for an 18-track study of queer romance mediated through screens. Opener “Kissing in Public” melts two-step drums into Rhodes pads, reclaiming PDA for Black queer visibility, while serpentwithfeet trades airy falsetto runs with Conrad on “Soft Side,” turning vulnerability into a duet. Production is helmed by Above Ground’s in-house trio, who layer dial-up-tone glitches under bedroom-soul chords, giving the album its VHS-warble patina. Cameos from Kehlani (“Bad Bitches”) and Teezo Touchdown (“The Last Time”) lend star wattage, yet Conrad’s feather-light tenor remains central, often dry-mixed to evoke voice-note intimacy. Even the raunchy “P.B.S.” with Lil Nas X plays like a flirtatious DMs thread that might turn into something deeper. Conrad paints a picture of modern romance that is messy, honest, and defiantly public, populating this project with queer collaborators and letting his lyrics oscillate between yearning and bravado. — Jamila W.

Halle, Love?... or Something Like It

By stepping from The Little Mermaid’s oceanic spotlight into solo waters with “Angel” in 2023—a song that channeled siren calls into R&B confessions of Black girl magic amid Hollywood glare—Halle’s days as a sibling act honing harmonies masked deeper dives into the currents of identity. After giving birth two years ago amidst all of the internet drama, we finally made it. Love?... or Something Like It splashes as her debut full-length, an inquiry into affection’s ambiguities where pop sheen meets raw pleas, questioning if what pulls you close counts as the real thing. “His Type” dismisses mismatches outright, opening with “You’re looking for his type, but I’m my own design,” lines owning curves and confidence that don’t bend to molds, her delivery a strut through self-love that reclaims the gaze. “Heaven” ascends to ideal intimacies, “If love is heaven, why does it feel like falling?” verses charting highs that teeter on drops, and “Back & Forth” sways through indecision’s loop, “We go back and forth like waves crashing unsure,” admitting the pull despite the tide’s toll. “Braveface” masks the cracks with “I wear my braveface like armor in the rain,” while verses peel back how smiles shield storms inside. “So I Can Feel Again” reunites siblings on renewal’s edge, Chlöe trading “Let me break so I can feel again” for shared scars that scarify strength. — Jamila W.

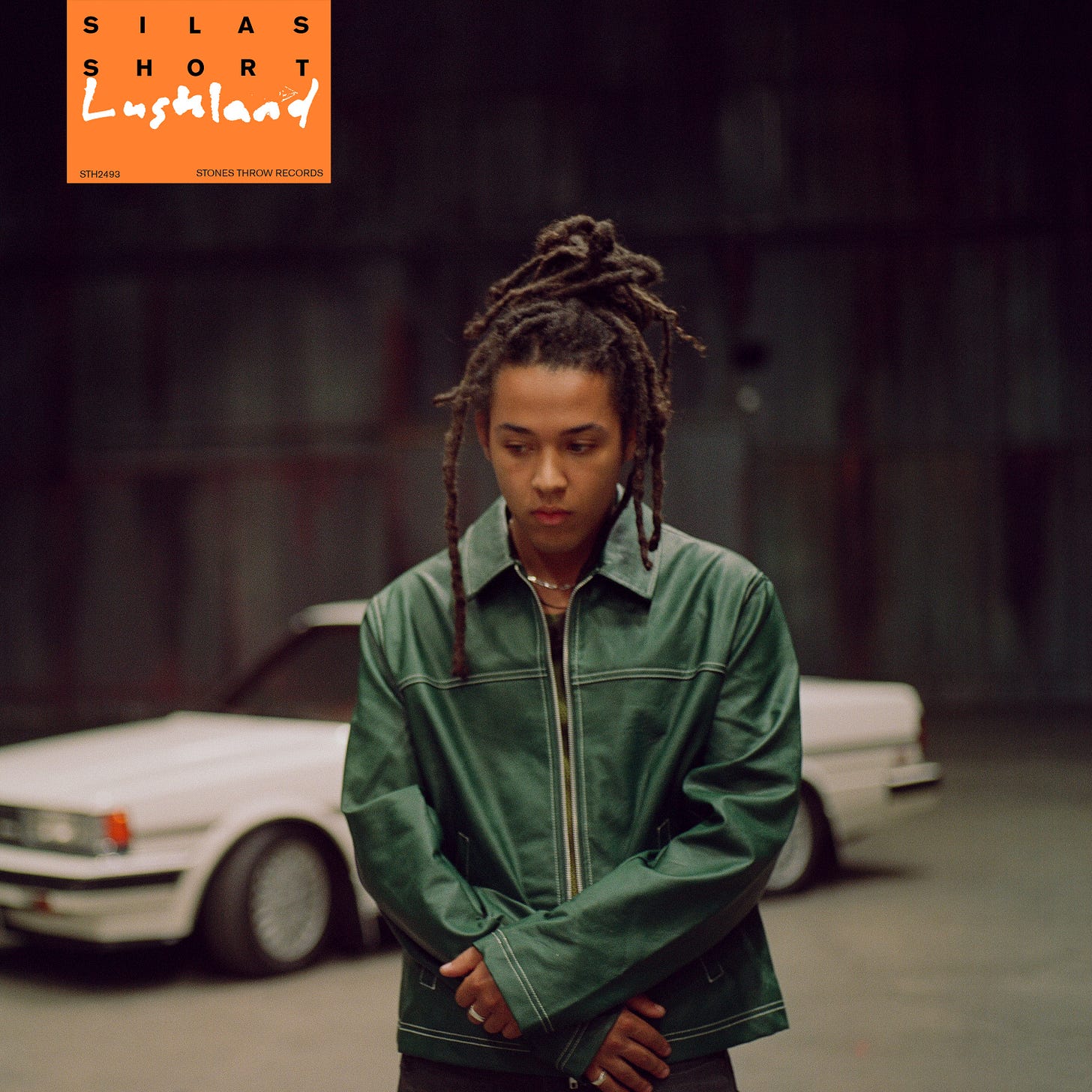

Silas Short, Lushland

Four years after arriving in L.A. with a car full of demo reels, Chicago-raised multi-instrumentalist Silas Short debuts on Stones Throw with a 12-song love letter to mid-‘90s neo-soul. Tracked mostly at the label’s Highland Park studio, Lushland blends nylon-string guitar, MPC-programmed drums, and Fender Rhodes into pocket-sized grooves—each mixed to feel like late-afternoon sunlight on cassette hiss. The singles trace Short’s journey: “L-Train,” written on a Red Line commute, captures city-watching wonder; “Guy,” later remixed by Karriem Riggins, flips unrequited lust into falsetto-stacked doo-wop. Gospel roots surface in stacked choir refrains, a nod to jam sessions with his father in Milwaukee church basements. The record’s handmade warmth, right down to Short’s hand-painting the vinyl center labels, places him in Stones Throw’s lineage of analog auteurs carving soul from humble tools. — Harry Brown

KIRBY, Miss Black America

KIRBY recorded her long-awaited debut in a studio on the Dockery Plantation to underscore that sense of duty and declared that the album should take us to Mississippi. She has long written pop hits for others, but Miss Black America finds her telling a family story rooted in the Mississippi Delta, where her ancestors toiled. The 12‑song collection is a love letter to the rural South, exploring how land, church, and family shape one’s worldview. The title track offers the thesis outright: “You wanna free us pay them teachers like they senators … I made a million and I never went to Harvard,” she sings, turning a political demand into a personal brag. Big K.R.I.T. responds not as a guest star but as a neighbour, rejecting stereotypes and insisting that Black prosperity exists beyond performing for white comfort. Throughout, KIRBY keeps tasks and rituals at the centre—“Bettadaze” counts blessings over a rolling groove; “Mama Don’t Worry” reassures a parent with promises built on work rather than wishful thinking; “Reparations” uses the title word as a ledger entry rather than a slogan; and “Afromations” recites affirmations like children learning chores. Even the flirtatious “Thick n Country” stays grounded by tying sensuality to soil, while guest Akeem Ali adds hometown swagger without turning the track into a caricature. By writing from the perspective of a daughter and a neighbor, KIRBY turns her return home into a portrait of daily strength. — Imani Raven

Debórah Bond, Mother’s Finest

During her twenties, Debórah Bond entertained audiences in various clubs across Philadelphia. Leading the Bond Girls, her singing emitted a calmness reminiscent of the peace felt after a hard day’s work. While crafting her first solo album, DayAfter, she balanced late-night shifts as a nurse. The album’s songs were born from exhaustion, exploring the subtle acts of healing heartbreak in solitude, after everyone else had left. Her most recent album, Naomi’s Finest, a tribute to her mother, builds on that initial composure. Moving between the soulful warmth of neo-soul and simple acoustic arrangements, she reflects on women like her mother, unsung heroes who support everything without seeking recognition. Yet, her aim is not weariness but a plea for consistency—not flashy romance, but a persistent commitment. Her vocals remain steady and purposeful, drawing your attention without becoming more intense. Bond returns to a central theme: persistence doesn’t require grand gestures. Instead, she quietly and steadily embeds it within these melodies by navigating the world with patience is sufficient. There’s no need for drama or elaborate displays. It’s about perseverance, thoughtful reflection, and the willingness to carry forward what has been given. — Imani Raven

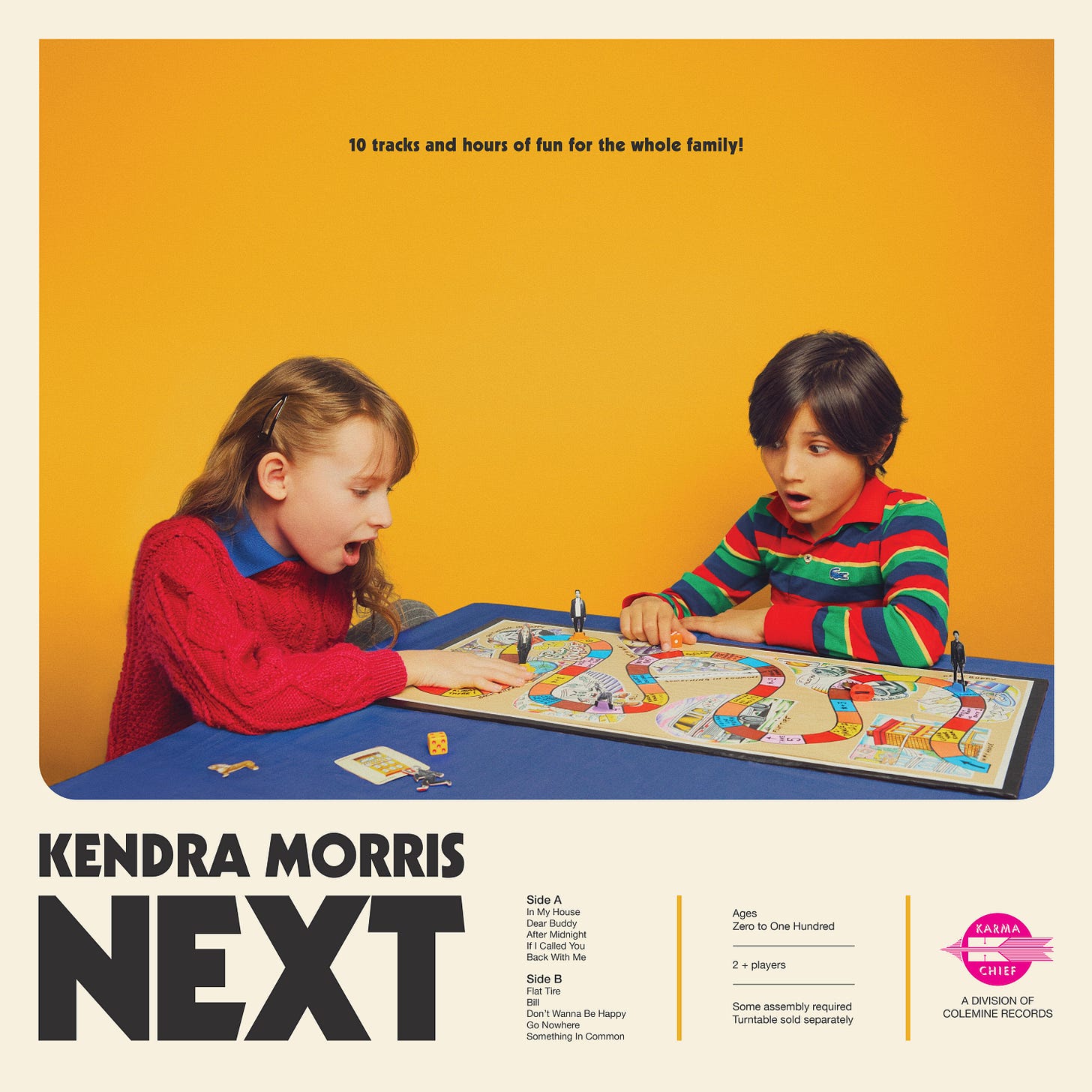

Kendra Morris, Next

After years of making cinematic soul records, singer‑songwriter Kendra Morris took a step back and built Next from the ground up, co‑producing it with Leroi Conroy and recording parts of it at Portage Studios in Colorado and in her own Brooklyn apartment. She wrote demos at her desk with a guitar, drum loops, and a Casio keyboard, and plays guitar throughout the finished album. Hence, this approach results in a more intimate, handheld feel compared to the widescreen polish of her previous work. “If I Called You” started as a slow guitar sketch before Morris and guitarist Jimmy James turned it into a breezy track reminiscent of Prince’s late‑70s work, complete with a Paisley Park‑style solo. “Flat Tire” links Kingston and Bushwick by pairing Ray Jacildo’s organ and piano with Morris’s AM‑radio‑ready voice, creating a lo‑fi reggae bounce. “Bill” is a playful ode to a recurring figure who pops up in different guises, and the delicate “Dear Buddy” functions as an open letter to her young daughter, its tender poetry and fragile strength forming the emotional core of the album. Even upbeat joints, including “In My House,” invite head‑nods while revealing shades of self‑reflection, and “After Midnight” and “Something In Common” explore raw convictions and compromise. — Imani Raven

Nourished by Time, The Passionate Ones

Marcus Brown’s catalog has been building toward this: Erotic Probiotic 2 drew attention to the voice, the Catching Chickens EP showed the reach, and The Passionate Ones pulls love songs and work songs into the same room. He introduces the stakes right away. “Automatic Love” tests desire against collapse and throws out a line as plain as a diary entry—“my body won’t feel nothing”—which makes the risk legible without embroidery. “Max Potential” is even more direct, with the fear stated in seven words—“Maybe I’m afraid of the future”—then the song proceeds to measure that fear against the need to try anyway. The set keeps circling the cost of moving through the day and the pull of connection. “9 2 5” reads like a work memo written by a person trying not to disappear inside it. “Idiot in the Park” and “Crazy People” capture the city’s public theater without lasting judgment. The title track steps back and asks a simple question—“Am I a ghost?”—which turns the whole record into a check on presence, not performance. Across the album, he avoids the lifted-nose stance that plagues records about modern life. He keeps it close to the body and the block, switches between tenderness and blunt talk with no stylized bridge, and lets repetition do the work that thesis statements usually fake. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Tanika Charles, Reasons to Stay

Tanika Charles sings like she’s opened every wound just wide enough for the groove to cauterize it. Her fourth LP trades previous rom-com heartbreak narratives for familial fault-lines, stacking Chi-Lites-style string swells and clipped hi-hat shuffles against lyrics that name-check abandonment, reconciliation, and inherited shame with unflinching clarity. “Don’t Like You Anymore” drapes smoky B-3 chords over a head-nodding pocket, her phrasing dipping into husky low notes before vaulting into a trembling melisma that cracks exactly where the story does. Producer Scott McCannell and mixer Kelly Finnigan infuse every rim-click and tambourine shake with analog hiss and ribbon-mic saturation, lending mid-tempo burners like “Talk to Me Nice” the warm, vintage sound of a lost 1973 acetate without ever sounding like a costume. When Clerel’s smoky tenor enters on the Gamble-and-Huff-tinged “Win,” the arrangement briefly slips into woozy psychedelic gospel before returning to its neo-soul core—a reminder that Charles, even in her most vulnerable confessions, never lets the pocket drift. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Madison McFerrin, Scorpio

With Scorpio, Madison McFerrin turned wedding savings into an album about walking away from an eight-year engagement, a decision that reshaped her life and sharpened her writing voice. That real-world pivot is the frame that holds these songs about choosing self over inertia. The track that matters most to the story is “I Don’t,” which begins, “We were supposed to get married today,” and keeps returning to the blunt refrain “I guess I don’t,” a refusal written without venom that still lands like a door closing. She uses a different register for “Fighting for Our Love,” confessing, “Shoulda never got to know you so well… You had me fightin’ for our love,” and the repetition earns its keep because she’s not selling resolve, she’s documenting how compulsion sounds when you finally call it by its name. “Ain’t It Nice” moves with a different kind of confidence, teasing “Is it hard to keep me out your thoughts… Told you I could always change your mind,” which reads less as conquest and more as someone relearning power without apology. As one of the standouts, she threads heartbreak into rebirth without dressing it up, keeping the language clear and the stakes human, and the cumulative effect is simple to name—the voice of an independent artist writing from the center of her life rather than around it. — Koda Lin

BOY SODA, SOULSTAR

You may sometimes be required to make what you want yourself. BOY SODA knew that. He has discovered the right people—musicians, singers, and friends—to help him turn what he felt into what you could hear. This is how SOULSTARwas formed. The album, which carries heartaches, family histories, and the things that only one can learn over the years. “Lil Obsession” is catchy, the type of song one cannot forget without force. In “Never the Same,” the author looks inward, and in “Blink Twice,” the saxophone does the talking. This is not a display of egos when he is with Dean Brady on their trip to “4K.” It is all about harmonizing voices so that they sound as one. He is no one in this world, attempting to play at imitating people, or to follow streams. He is crafting his own definition of whatR&B can be in the present times with the real stories to tell, clean production, and the type of warmth that makes you feel like you have known him a long time. — Phil

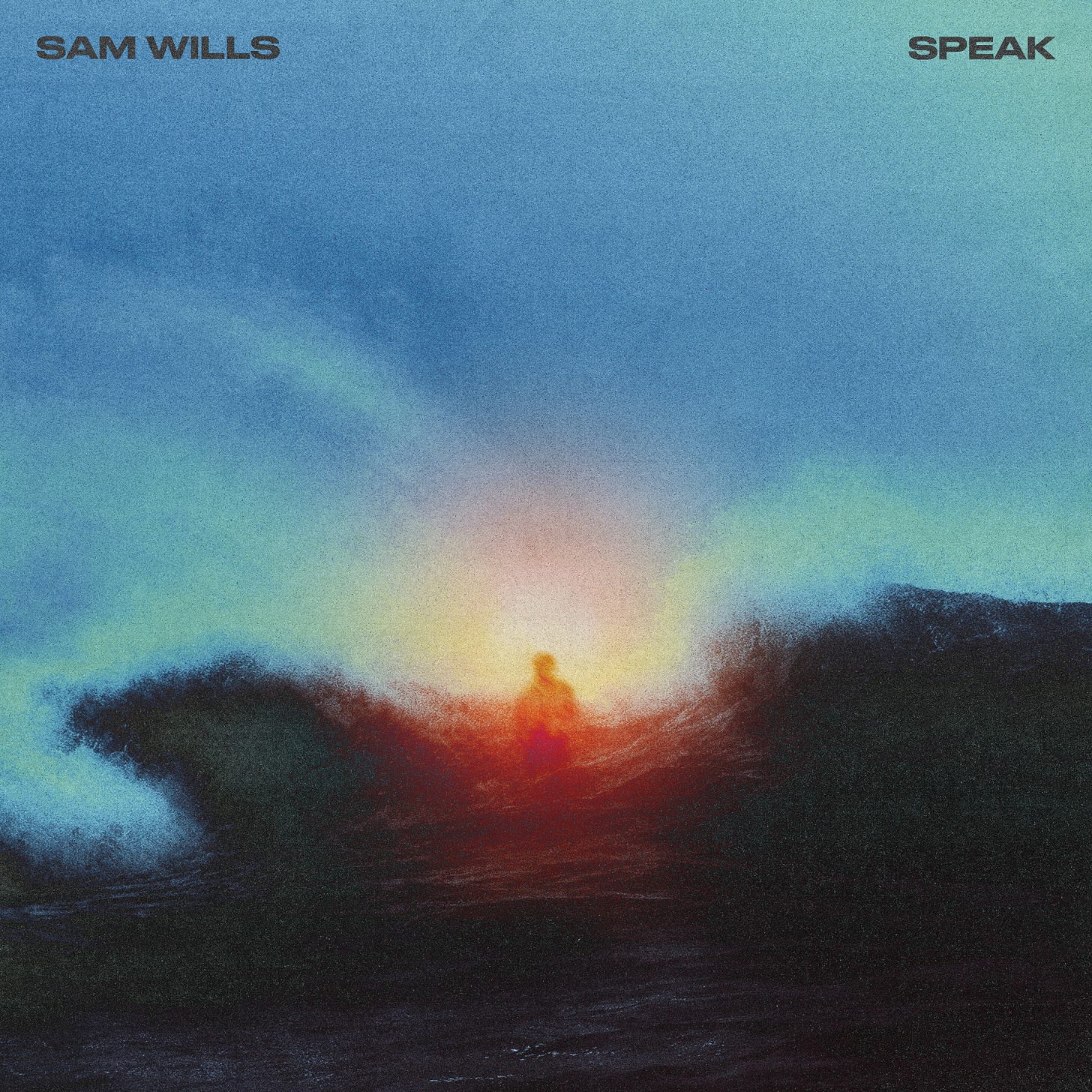

Sam Wills, Speak

It is unbelievable that it has been four years since Breathe. That was a swinging blow by Sam Wills, and that was a sleeper. With its second full-length LP, Speak, Sam demonstrates how an artist could gain time to figure himself out. He claims he had a hard period because his star was in the dark, he was caught up in what he had not produced rather than what he had created, and he was going round and round. Such burnout is familiar to anyone attempting to do something meaningful. Talking was his means of making some sense of it—a work of honesty and little discoveries about the value of living in the present. The songs are intimate yet not depressive, and the grooves are slow yet tolerant because the feeling is just beneath the skin. It is music to listen to when you are attempting to find the way back to you. — LeMarcus

duendita, A Strong Desire to Survive

Queens vocalist-producer duendita distills trauma, healing and righteous anger into a ten-song set. Field-recorded subway rumbles and detuned upright-piano chords underpin opener “Why I Didn’t Report,” where her caramel alto floats above clipped news-broadcast samples to confront assault silence culture. Throughout, she toggles between choral stack-ups worthy of Renaissance polyphony and skeletal piano ballads like “Baby Teeth,” recorded in her bedroom with a single Zoom mic. She self-produces most tracks, but MIKE slips in lo-fi drum palettes on “HTP,” echoing their New York DIY lineage. The album’s sequencing feels nonlinear—short interludes bleed into full-length songs, mirroring the circular nature of recovery. By the closing voicemail collage “All Mine — June 11, 2019,” she reframes survival not as a destination but perpetual motion, each track a checkpoint in reclaiming bodily autonomy. — Jamila W.

Yazmin Lacey, Teal Dreams

Yazmin Lacey first caught ears in Leeds’ jazz cafes with her 2017 Black Moon EP, which layered neo-soul warmth over spoken-word poetry drawn from late-night journals on racial reckonings and quiet yearnings. All of this led to building Voice Notes’ (her debut album) intimate dispatches in 2023 that traded club polish for raw vocal takes recorded straight to phone. Teal Dreams drifts in as her fullest canvas yet, that bathes those roots in dub and soul to explore love’s hazy horizons where introspection meets invitation. “Teal Dreams” washes in with “In the teal light, I see your shadow dance,” verses painting nocturnal visions where colors bleed into confessions of seeing someone fully amid the blur, the central passage repeating “Dream with me, teal dreams” like a lullaby that pulls you under into shared subconscious tides. “Two Steps” steps lighter on relational rhythms, opening “Two steps forward, one glance back” to chart the tentative sway of opening up, admitting how hesitation holds the absolute sway in bonds that build slowly, her voice curling around admissions that turn pauses into progress. “Wallpaper” peels back facades with “You’re just wallpaper in my mind’s room,” a gentle gut-punch at loves that fade to background noise, verses sifting through memories that stick like patterns you outgrow, the hook urging to strip it all for the bare walls beneath. As her second album, it flows as Lacey’s ode to loving through layers, tracks that invite you to linger in the liquid spaces between hearts. — Alexandria Elise

Greentea Peng, Tell Dem It’s Sunny

Greentea Peng’s new album suggests she may enjoy a spliff sometimes. Her music has always hovered between the spiritual and the streetwise, but Tell Dem It’s Sunny feels like a declaration of self‑reinvention. The record works in a dubby trip-hop and woozy neo-soul style. “Stones Throw” is a future‑soul high point where her voice moves between drum‑and‑bass pulses and haunting strings, conjuring both urgency and calm. The lyrics shift between politics, spirit, and odd humor. They move over loops and heavy bass lines. She worked with collaborators such as Earbuds, Samo, and Wu-Lu. “Create or Destroy 432” plays with the idea of choice, while “TARDIS (hardest)” channels defiance; over a filter‑distorted sermon, she warns, “There are no insecure masters/No successful half‑hearters,” calls to commit fully. It fits with hints of healing and spiritual thought. On “One Foot,” she leans into bluesy soul and asks, “Is it too late for me?” inviting anyone who has doubted their path to join her in taking a leap. The album pushes aside any doubt as it makes its play for Album of the Year in early Spring. — Jamila W.

Rochelle Jordan, Through the Wall

Rochelle Jordan has been quietly redefining club‑ready R&B for more than a decade. After her 2014 album 1021 and the adventurous Play With the Changes, she returns with a project that treats the dance floor as a sanctuary rather than a trend. Jordan describes Through the Wall as a dedication to God and to herself – an album born of breaking through psychological and professional barriers and celebrating the artist she has become. The songs are steeped in the deep grooves of Chicago house and New York ballroom and coloured by her Canadian and UK roots. “Crave” rides a rich, pulsing bass line and invites listeners to get lost in its hypnotic swing, while mid‑tempo numbers include “Never Enough,” “Get It Off,” and “Bite the Bait” recall the seductive pull of ‘90s R&B. She pays homage to UK garage on Close 2 Me, whose bassline demands a loud soundsystem and thick smoke. On “Ladida,” Jordan flips from airy singing to a swaggering rap over a shuffle beat, accompanied by a playful vocal tic that conjures memories of Crystal Waters and basement raves. She sounds empowered, writing a love letter to freedom and asserting her individuality over industry fads by crafting a dance record that moves both body and spirit. — Tabia N. Mullings

Khamari, To Dry a Tear

The Boston‑raised, LA‑based singer put out a strong debut in 2023, then returned with a follow‑up that drops the defenses and writes directly from the push and pull between commitment and escape. The opener “I Love Lucy” starts with the line “Lucy wanna build a home up,” which frames the whole album as a negotiation between steadiness and drift, and by “Head in a Jar” he is picking through the claustrophobia that comes with being pedestal‑ed in a relationship, humming “You keep my head in a jar” as if naming it might shrink it. The writing keeps toggling between small domestic details and the big questions no one solves alone. “Close” carries the ache of being in the same room and still out of reach, and it reads like a long text you draft and delete a dozen times before sending. “Sycamore Tree” braids a memory of D’Angelo into a vow to grow up without getting hard, and the lyric questions are blunt rather than poetic fancy, the kind you mutter when the house is quiet and you finally let yourself be honest. Across these songs, he builds a patient emotional vocabulary from simple words, trading in faces, rooms, apologies, and the little tics that make a romance feel specific, and the melodies follow the writing rather than the other way around. The record earns its title by sticking with discomfort until it turns into a decision, and by the end, you can hear a young songwriter choosing candor over cool. — Phil

Jon B, Waiting On You

When Jon B released his last album, streaming services were just beginning to eclipse CDs; thirteen years later, he returns with Waiting On You, a set that shows how much he has grown without abandoning the sensuality that made him a 1990s icon. “Chozen” opens the record with a poetic flourish—he compares his lover to a “golden divine” vision and frames desire as a sacred jury deliberation. “Natural Drug” and “Pick Me Up” recall his earlier days, blending past and present. “Still Got Love” shifts into an ‘80s‑inspired dance groove as he reassures an old flame, “You still gotta thing for me/You got love.” “Natural Drug” takes sensuality to a near‑psychedelic level by casting a lover’s presence as a narcotic high, and “Show Me,” a duet with Alex Isley, turns harmonised ad‑libs into a conversation about vulnerability and guidance, and “Understand” with Tank carries a grounded energy. “Bandit In the Night” shines with its detailed production and strong performance. “Still Got Love” counters that with a light, joyful feel. The production supports the tracks without overpowering Jon B’s voice, a result of careful effort over the years, sharpened by creative space during the pandemic. Where some return projects lean on nostalgia, Jon B uses memory to amplify new wisdom. Waiting On You proves his staying power in R&B. — Tai Lawson

iyla, Weeping Angel

iyla builds a voice through short forms—the sharp, heart-forward War + Raindropsand the more confrontational Other Ways to Vent, a run that also put her across from Method Man on “Cash Rules”—before arriving at a debut that turns private upheaval into plainspoken conviction. With Weeping Angel, it’s a record of grief after her mother’s passing, of the stubborn self-belief that follows, and of the messy negotiations between desire and boundaries. The writing pulls tenderness and steel into the same breath. “Corset” sets the tone with rule-setting language and astrological self-inventory to “read the signs,” as “Overboard” uses the pull of water as a map for obsession and second thoughts, not with florid imagery but with moments of plain admission and recoil. The album’s most tender thread runs through “Blue Eyes,” written in the shadow of loss and carried by the hope that memory can still be a refuge where the perspective stays personal, not performative. She writes her way toward steadier love, starting with “Twin Flame,” imagining the version of partnership that doesn’t demand constant triage, while “Wild” and “Strut” argue for autonomy without turning it into a slogan, each one favoring decisive phrasing over posture. Even when she blurs sacred and sensual on “Ave Maria,” the line is less about provocation than self-permission, a reminder that devotion and embodiment can share the same room. Weeping Angelis direct, sometimes playful, sometimes cutting; images arrive only when they earn their keep, and what ties it all together is her insistence on naming things (hurt, want, lines in the sand) and trusting that simple, exact words can hold big emotions without decoration. — Imani Raven

Coco Jones, Why Not More?

Almost three years after “ICU” made her the new voice of R&B yearning, Coco Jones answers her own question—why not reach further?—with a 14-song debut. Writing every lyric herself, she toggles between airy head-voice confessionals and Trap&B bounce, often in the same song. Jones is done asking permission to explore or to demand more for herself. StarGate, Aaron Shadrow, and Jasper Harris flourishes underpin “Taste,” which flips a sly “Toxic” interpolation into a flirtation anthem, while Cardiak and Wu10 recreates the Lenny Williams classic on “Here We Go (Uh Oh),” now her first Adult R&B Airplay No. 1. Ballads like “Other Side of Love” show a studio strategy Jones describes as “patience sessions,” letting melodies breathe rather than chasing radio-ready hooks. “AEOMG” borrows a phrase from Luther Vandross, using it when she can’t find the words to express her desire, but rather than treating the homage as a gimmick, she leans into the awkwardness of romance and turns it into a moment of honesty. The result is a debut whose emotional center is “By Myself,” an R&B power-waltz that affirms therapy, solitude, and self-trust—future tour fodder as she balances music with her role on the final season of Bel-Air. With these candid stories together with a voice capable of warmth, grit, and vulnerability, Jones writes her way out of a pigeonhole and into a place where her questions become affirmations. — Tai Lawson

🎧🎧🎧