The 80 Best Rap Albums of 2025

A list for people who listen first and argue later. No declarations, no coping, no “rap is back” sermons. Forget the headlines and the mood-board takes. These records held up when nobody was watching.

Year-end rap talk loves a scoreboard. It turns albums into campaigns, turns attention into math, turns “who didn’t chart” into a punchline that’s supposed to end the conversation before it starts. This list doesn’t move like that. The “who doesn’t chart” obsession is a lazy way to avoid listening. It pretends the only music worth naming is the music that already got named a thousand times by the same machines, the same feeds, the same arguments. A rap album can miss the mainstream pipeline and still hit harder, last longer, and carry more detail than the stuff built to spike a weekend.

And yeah: 2025 was one of rap’s best years in a long time. Not because the timeline needed a comeback story, but because there was a real surplus of albums with muscle, voice, and replay. Too many lanes stayed active at once for any single narrative to cover them, which is the point. Albums that keep opening up after the first pass, projects that don’t hide behind filler, records with writing that holds pressure, and performances that sound like somebody meant every bar. No gold stars for “impact,” no bonus points for volume, no penalty for being outside the loudest rooms.

These are the best rap albums of 2025. Start anywhere, bounce around, double back when something catches, and let the music do its job.

Lloyd Banks, A.O.M. 3: Despite My Mistakes

Twenty years removed from his G-Unit glory, Lloyd Banks has spent the past decade dismantling his own mythology. The punchline-heavy wordplay that defined Hunger for More and Rotten Apple gave way to something more introspective on the All or Nothing series, and Despite My Mistakes arrives as the third installment, eighteen tracks of New York rap that trades swagger for self-examination. Where Banks once delighted in linguistic acrobatics, he now prefers technical rhyme schemes wrapped around conscious reflection. “Determination” opens with piano-laced boom bap addressing how he’s returned moving differently, and “If I Wake Up” suggests he should already be dead considering what he’s become and the sacrifices made. Styles P arrives on the title track to add gravity to Banks’ admission of flaws, while Ghostface Killah on “Endangered Innocence” connects the album to lineages of East Coast veterans who’ve watched the game shift beneath their feet. “Art of Rap” stretches past five minutes, giving Banks room to unpack technique and legacy without rushing. “Perfect World” imagines scenarios that will never materialize, and “Traumatized” documents damage without seeking sympathy. What’s gained in lyrical sophistication gets lost in entertainment value—the punches that made him essential have been replaced with pensiveness that doesn’t always justify its own weight. — Murffey Zavier

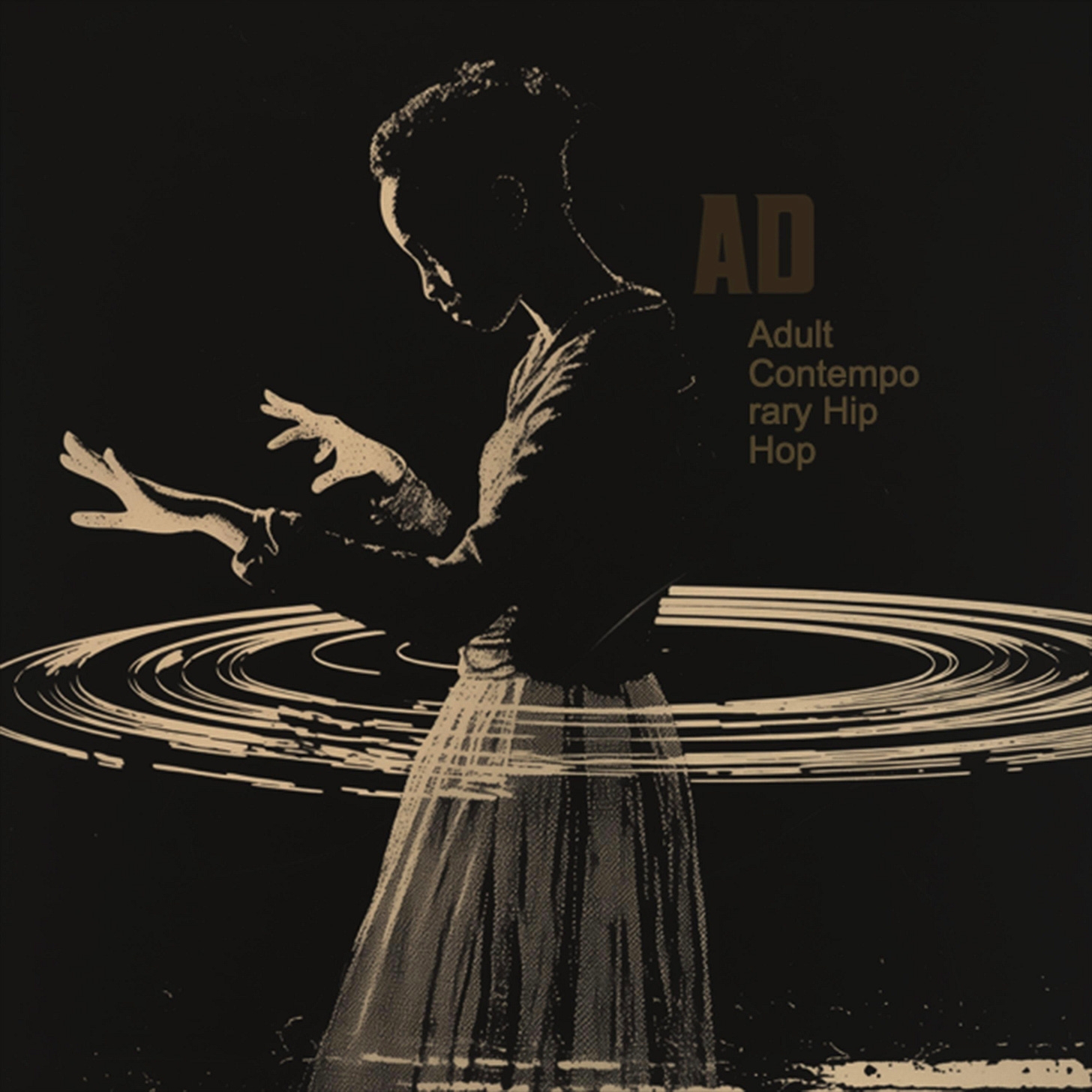

Arrested Development, Adult Contemporary Hip Hop

The Atlanta collective leans into middle-age wisdom with unabashed confidence, with Configa crafting beats that breathe with jazz-inflected patience, where the rapping on this project navigates themes of melanin pride and mortality. They abandon any pretense toward youth appeal—this music belongs to grown folks who’ve survived decades in hip-hop’s margins. Speech remains the anchor, his delivery weathered but purposeful, as he addresses a generation that grew up on “Tennessee” but now grapples with mortgages and Medicare. The album’s boldest gambit lies in its title—openly courting the demographic that radio programmers target with smooth jazz and coffee playlists. Yet beneath the self-aware branding lurks genuine artistic ambition, with compositions that reward close listening and political messages that cut deeper than surface-level consciousness. Over the course of an hour, the record occasionally meanders, but when it connects, it proves that hip-hop’s elder statesmen still possess vital perspectives worth documenting. — Randy

Freddie Gibbs & The Alchemist, Alfredo 2

Back in May 2020, when a rented Hollywood condo doubled as a photo set, Freddie Gibbs and The Alchemist shot the Alfredo cover—silver spoon dripping over fettuccine—and forged a rapper-producer pairing that re-centred gangster rap around cinematic understatemen. Five years, two solo detours, and a globe-spanning tour later, they resurface with a sequel, timed for the Summer of Spittas era drop so fans could blast it at cookouts before campaign ads drown out the block speaker. Gibbs bends flows to every contour—baritone croon here, double-time sprint there—keeping the tension taut with the help of Anderson .Paak’s Oxnard rasp marinates “Ensalada,” Larry June glides Bay-area affirmations through “Feeling,” and JID’s Atlanta syllable-storms torch “Gold Feet,” each cameo upping the heat without stealing the plate. The Alchemist rows deep-fried guitar through dusty strings on “Mar-a-Lago,” chops Peruvian surf rock for “Empanadas,” then lets flute and sub-bass circle like vultures on “A Thousand Mountains,” all tracked to two-inch tape with engineer Eddie Sancho punching edits by hand. The new set weighs appetite against fallout; verses flip between five-star indulgence and the anxiety of someone eyeballing the exit while counting plates. We out here slammin’! — Brandon O’Sullivan

doseone & Steel Tipped Dove, All Portrait, No Chorus

The title is literal. doseone’s résumé stretches back to the late-’90s Anticon era, but he hasn’t sounded this alert in years. After decades of assorted groups and side projects, he cut All Portrait, No Chorus in a matter of months, sending beats back and forth with New York producer Steel Tipped Dove and bringing in turntablist Andrew Broder to scratch over the results. The process was sparked when Doseone heard a preview of a ShrapKnel record and felt compelled to reconnect with a new generation of off-center emcees. By mid-January 2024, he had five songs drafted and soon invited Open Mike Eagle, M Sayyid, billy woods, Fatboi Sharif, and Myka 9 to trade verses. Dove paints with “every color on the palette,” doseone observes, which means the tracks flip between jittery loops and melancholy guitar figures, leaving the veteran “skating languid figure 8s” before landing “lyrical triple axels” when the beat calls for a flurry. The record is lean and hungry rather than nostalgic. doseone’s pen darts from adolescent recollections to surreal threats, punctuated by the guests’ deadpan humor and rolled-r cadence. Without traditional hooks, each verse feels like a snapshot in a broader portrait of lives lived on the margins, and the collision of these perspectives turns the project into more than a mere collaboration.— Phil

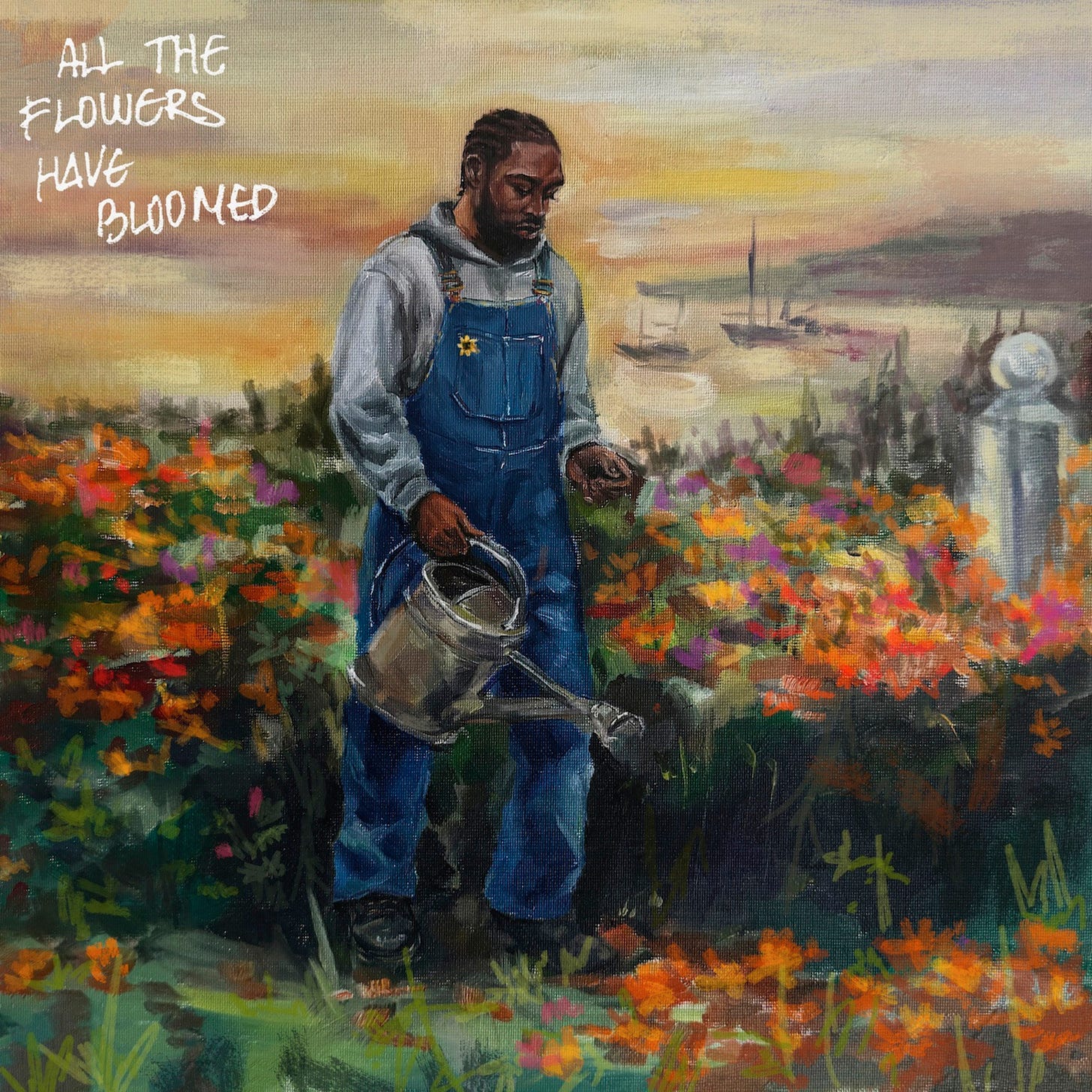

Kofi Stone, All the Flowers Have Bloomed

With this album, Kofi Stone’s style doesn’t shift drastically, but it’s refined. He grew up in Birmingham’s Selly Oak after a family move from Walthamstow, and from that mix of working-class roots and London-edge he forged his voice. A poet grandfather, a father steeped in blues and hip-hop, late nights at studios—these built the tools he uses on All the Flowers Have Bloomed. On “Thorns,” he lays out sleepless drinking, therapy sessions, and parenting in the midst of mental health struggles. There’s no neat redemption or uplift; the verse ends in a question: Is God teaching him a lesson? “Seeds” recounts the move to Brum-town, labels trying to dumb down his ambitions, plus a neighbor housing his family after a fire. The closer, title-track “All the Flowers Have Bloomed,” finds Stone almost celebratory. He opens with a toast (“Everybody in the house, how you doing tonight?”) and pulls together the thesis: the hard years, the planting, the waiting. “All the flowers have bloomed, just like it’s the middle of June.” Yet there’s no ignoring what came before. The sound brings live instrumentation, soulful touches, elements of jazz, funk, and hip-hop layered beneath Stones’s settling voice. The album becomes a map of perseverance, loss, legacy, and renewal. — Ameenah Laquita

PARTYOF2, Amerika’s Next Top Party!

Longtime LA partners SWIM and Jadagrace first discovered each other as babies, folding music into grouptherapy. sessions before an identity fall damaged their friendship, forcing them to piece together ashes into this invincible twosome, to the shock of the scene. They signed to Def Jam and their foot stays on the gas. Amerika’s Next Top Party! for their very frailty, their shade-throwing, into constructing every song as a comeback narrative where shade-throwing becomes a collective spotlight that makes the mess of relationships strained by fame shine. “Survivor’s Remorse” begins with therapist enquiries into post-traumatic stress, SWIM versing on blowing tires on the richest streets and swearing to climb mountains on his own, the chorus of Jadagrace urging him to break your spirit, to love, to kill your pride in rushing to falling anyway, the duo jumping on the cash in hand to paper over skeletons. “Out of Body” explodes with hell-escapes emblematic of hashtags, chorus flames of the extremist desire to lose all control, SWIM and Jadagrace harmonizing out-of-body inquiries that thwarts crash clubs into saunas as hands fly till roofs blaze. “Friendly Fire” rolls bedtime stories into volleys of diss and SWIM whacking Gram sending in blueprint manifestos and Jada grace tossing over the boy stories into survivorship crowns, pounding non-hostile betrayal to couple steel. Their introduction is a blast, with the first outing of SWIM and Jadagrace over their own personal traps. — Javon Bailey

Queen Herawin, Awaken the Sleeping Giant

As a member of the Juggaknots, Queen Herawin established herself as an incisive storyteller; her second solo album turns inward to chart a personal awakening. The title alone signals a shift, and Herawin says the project is about “waking up to your true self, to your inherent power, embracing it, and celebrating the entirety of who you are.” That mission is evident from the opener “Focus,” where she imagines blurring out background noise and resetting the aperture until life comes into view. Herawin moves through them with a diaristic pen that blends vulnerability and bravado, as she deals with every emotion (“Anger,” “Denial,” “Shame,” “Love”). Her intent comes through in the way she pairs battle-hardened delivery with self-interrogation. On the standout “Arrogant,” she spars with Poison Pen, confronting ego while staking her claim. “Manifest” brings Apathy and Mickey Factz into a cipher where she says that self-belief is a practice. Rather than focusing on technical feats, she writes her way through grief, pride, and renewal, witnessing a process of becoming rather than a finished product. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Pink Siifu, Black’!Antique

The thing about Pink Siifu’s discography is impossible to pin down. He has rapped over punk noise, crooned over funk, and produced gospel-inflected tapes, and Black’!Antique continues his refusal to be boxed in. The songs swing from clipped jazz loops and kinetic drum’n’bass to bluesy guitar vamps; in place of obvious hooks, Siifu layers chants, phone-call fragments, and street-corner conversations. Several songs serve as open letters to Birmingham and Cincinnati, mapping lineage and geography onto his internal map. Others, like the barn-storming title track and the driving “ALIVE & DIRECT,” feel like cipher sessions built to uplift friends as much as the audience. Siifu revels in cadences and slang that could only come from the communities he hails from, yet he never shies away from pointing out exploitation or the psychic cost of perseverance. The collage-like structure means that themes recur out of order with the search for spiritual balance, the memory of a loved one’s advice, and the grind of working-class life. Taken as a whole, the album reads like a scrapbook whose messy edges are deliberate, a sonic version of a family heirloom passed around at a reunion. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Aesop Rock, Black Hole Superette

Three decades into his career, Aesop Rock continues to find new corners of language to occupy. Black Hole Superette scales down his production but not his bar density, turning everyday observations into cosmic riddles. Over pared-down beats, he flits from horticulture to ancient libraries, boasting, “I’m all of Alexandria’s information in aggregate/Ruling elder giving you the hell that melt the valuables/Riddances, grid at my back, I’m in the diagonals/Evolving, shiv in his back, he shatter the manacles.” The humor that has crept into his recent work is here too; at one point, he cracks, “Sharpest teeth on the block, anyone who disagree is a bot/Yo, anyone who isn’t me is a cop.” Yet the album’s heart lies in its domestic details. On “Living Curfew,” he turns a house tour into poetry: “Lemme catch you up on the crib/I got a palm in the corner about as tall as the kid/I got a fig in the southern corner, it’s dwarfing the palm / A tiny peek into the florals we’ve been hoarding at home, Holmes.” He marvels at swifts roosting in a school chimney and debates whether to remove invasive snails from his fish tank, expanding small moments into meditations on our place in the universe. Guest appearances from billy woods, Lupe Fiasco, and Open Mike Eagle prompt him to sharpen his pen even more, but Black Hole Superette succeeds because it shows Aesop enjoying the world rather than merely escaping it. — Harry Brown

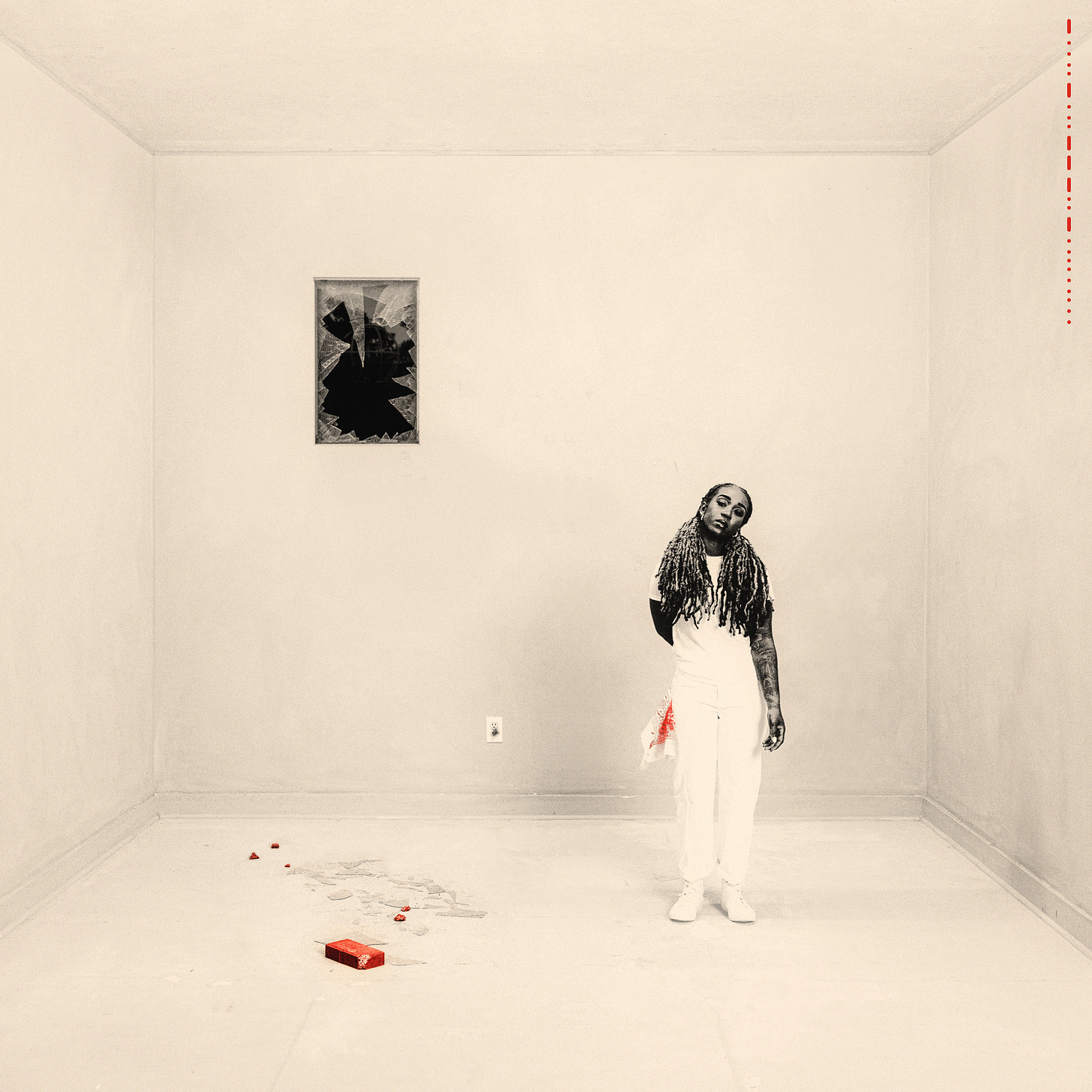

Jackie Hill Perry, Blameless

Jackie Hill Perry returned to hip‑hop after nearly a seven‑year hiatus, bringing with her the perspective of an author, spoken‑word poet, and mother. With Blameless, she built a conceptual “house” where each song occupies a room and together they form an examination of faith, the Church, and personal accountability. “The Home” invites us into that house by narrating a scene at a red house with a cracked window, knocks on the door, slips inside and wanders through rooms where greed and distraction lurk, and “Pride and Prejudice” she confronts her identity head‑on—“Indian in my blood/You can tell by the roots/Ain’t selling dream catchers/Everybody wanna be a prophet/‘Til it’s time tell the truth”—before the hook admits “Maybe I’m just relevant/Maybe I’m just arrogant/Maybe y’all need a therapist,” showing self‑examination and vulnerability. “I Ain’t Worried” finds her telling anyone who will listen that she doesn’t chase money or gossip, boasting, “Got four babies and they crazy call me Donda,” and dismissing online critics by saying, “Why you talking mess? It ain’t no flex to spin that gossip/When I spit that gospel.” Even the uplifting “Keep Your Head Up” carries depth; over bright keys, she urges weary women to look to heaven, reminding them that they are seated in heavenly places while cautioning against overthinking and self‑sabotage. Throughout Blameless, Perry knits theological reflection into conversational rhymes, blending admonition with encouragement to craft a record that feels like both a candid journal entry and a sermon in equal measure. — Murffey Zavier

Dave, The Boy Who Played the Harp

Dave cut his name out of the blocks of South London, Brixton blocks, with the one-take treatments, healing therapy sessions with Psychodrama in 2019, that revealed the scars of knife crime. He followed with the epics of family with We’re All Alone In This Together that put him three-and-a-half-meters taller than his contemporaries in UK rap, and The Boy Who Played the Harp that put his scars of heritage on the harp strings that turned scars into folk heroics of heritage and loss. “History” unravels generational threads with “Yeah, I sometimes wonder, ‘What would I do in a next generation?’/In 1940, if I was enlisted to fight for the nation,” verses tracing ancestral echoes from war drafts to modern drifts, James Blake’s keys heighten how pasts pluck at presents unbidden. “175 Months” confesses timelines to the divine, “Lord, it’s been 175 months since I last felt whole,” a raw reckoning of years stacked like debts, his flow pleading for grace amid the grind that shaped his grip on the mic. “Selfish” owns ego’s edge, “I’m selfish with my time ‘cause time’s all I got,” verses weighing solitude’s cost against connection’s claims in a balance that tips toward guarded growth. He takes the lineage and turns it into a living song, melodies that play harps over chronicles, turning the bruises into the music of diligently enchanted here. — Phil

De La Soul, Cabin in the Sky

They were visionary and taboo-breaking on several occasions. Despite the sunny nature of their music, released since 1988, the jazz-rap pioneers De La Soul already addressed the story of a girl sexually abused by her father on their second album. Artificial intelligence became a central theme for the trio in their AOIseries, which coincided with the turn of the millennium and, soon after, the horrific events of 9/11, in De La’s hometown of New York. They steadfastly distanced themselves from the gangster rap that was flooding their scene at the time. The world always listened to them, far beyond genre boundaries, for example, when they opened for The Flaming Lips or collaborated with the Gorillaz. Their return with Cabin in the Sky was unexpected. But Trugoy, one of the three MCs, didn’t live to see it. The album’s diverse range of expressive modes includes children’s and monster voices, gurgling scratches on the voice, a radio play with screeching and slamming doors, announcements for a breathing exercise, elegant choral singing, and even an introductory round at the beginning. It is a warm, sunny, and emotional work, as can already be seen in song titles such as “Sunny Storms,” “Cruel Summers Bring Fire Life,” and “Day in the Sun (Gettin’ Wit U).” Besides the breadth of themes and vocal delivery, the sound design is also multifaceted, thanks to Pete Rock, DJ Premier, Nottz, Jake One, and others. With the help of a stacked feature list of the year, including everyday philosophical musings, De La Soul goes a big step further and builds upon the historically significant works of their early years. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Miles Cooke, Ceci N’est Pas un Portrait

Miles Cooke has kept to the underground. As his debut full-length, it is a striking catalog of grief, satire, and American decay. The album opens with “Negus,” where he hears fate whispering as he watches “for the levee breaking” and admits to drinking to kill the echo of exhaustion. On “The Book of Job Part II,” he likens his own suffering to that biblical story, wearing a “Janus mask” and painting scarlet letters across personas while quoting commandments from writers like Baldwin and Butler. Black humor runs through the project; on “Zugzwang,” he complains about an upstairs neighbor and, with Defcee egging him on, imagines burning down the building just to stop the stomping. The bleak midsection, “A Firsthand Account” and “Sangria,” pairs fascism and corporate greed with everyday terrors, surveying farmland and the Bible Belt, then admits that memories are “a fickle bastard” floating in a glass of sangria. Cooke’s writing peaks on “The Devil Part Didn’t Change,” where he spits about “temples built off drug money” and being asked to leave God out of his search for meaning, and on the closing numbers, he implores himself to “dismiss the fear of being you” while dreaming about breaking free from New York’s grind. Throughout, his raspy delivery and dense wordplay evoke the Black humor of Ginsberg and the cartoon villainy of MF DOOM. The record never settles into a single mood but instead draws a portrait of modern Black life that moves from rage to tenderness to sardonic laughter. — Harry Brown

Wildchild, Child of a Kingsman

Spot the scene and you can see it, mic in hand, the former Lootpack emcee working the front row and grinning like a dad proud of his section, which fits a project built after a long stretch given to raising his son Miles, known to most as Jack Johnson from Black‑ish, and you hear that decision echo in the writing’s emphasis on duty and inheritance. “Change for My 2 Cents” turns coins into conscience, counting out what value even means in a season of shortcuts, and the verses read like kitchen‑table talk sharpened into bars. “Season of Kingsmen” steps past nostalgia and into a pledge for how to carry yourself when younger heads are watching, and the line “less viral, more vital” lands like a mantra you can scribble on a sticky note and keep above your desk. Around those anchors, the record keeps naming the work. “A Kingsman’s Flowers” feels like handing roses while people can still smell them. “Wing Chun” flexes discipline rather than anger. “Bat Signal” calls the neighborhood together without sermonizing. Even when he lets guests into the room, he writes as a host who knows what the house is for, giving space and then tying every verse back to community, craft, and the idea that grown rap can still be warm and welcoming. There is bragging here, but it is the kind that points outward, to teachers, partners, and kids who need a map. — Harry Brown

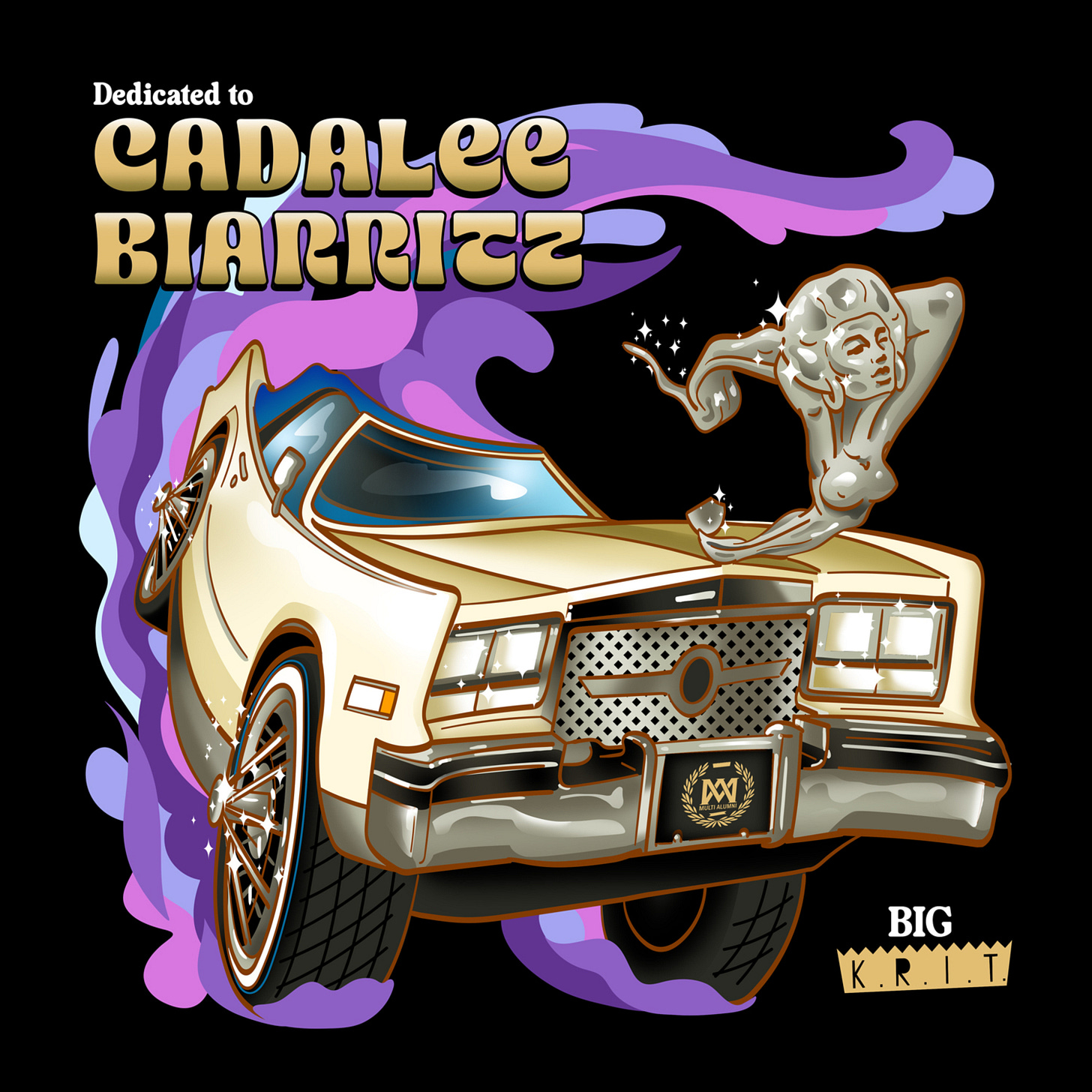

Big K.R.I.T., Dedicated to Cadalee Biarritz

Justin Scott built his reputation in Mississippi as someone who understood that Southern rap could be introspective without losing its trunk-rattle, that you could talk about God and grind in the same breath without contradicting yourself. After leaving Def Jam and launching his Multi Alumni label, K.R.I.T. gave us 4eva Is a Mighty Long Time, a double album that remains one of the decade’s most ambitious rap statements. The years since have been uneven, experiments that didn’t always land, but Dedicated to Cadalee Biarritz finds him back in the driver’s seat literally and figuratively. The album’s named for his car, and that’s exactly what it sounds like—31 minutes of trunk music structured around radio commercials for Grillz by Scotty, CJ Customs, and Spokesnvogues, turning the whole thing into an extended love letter to vehicles and the freedom they represent. “Gotta Do It” blends cloud rap atmospherics with dirty south bounce, looking back to how the players did it before everything got complicated. There’s a Zapp influence on “Hi Def” that gives the track a pop-rap sheen without losing the grit, while “The Mileage” is exactly what it sounds like—K.R.I.T. talking about cranking the volume in his big body, the bass doing half the work. “Not in the Whip” takes a more aggressive approach, refusing to engage with politics or petty disputes when he’d rather be driving. — Randy

PremRock, Did You Enjoy Your Time Here...?

Long before his association with Backwoodz Studioz and collaborations with billy woods, PremRock sharpened his pen on poems and performance art. That literate sensibility transformed into Did You Enjoy Your Time Here…?. He opens the album with “Void Lacquer,” a song about finishing what you start and surviving restaurant shifts, boasting, “A finishing touch only matters if you finish enough/Like I’ma finish you and still get us through this dinner rush.” He reflects on aging and sobriety—“Arrive five years older, three years late/Salt and pepper smolder, California sober”—balancing wit with confession. On “Doubt Mountain,” he calls in sick with “Irish flu” and jokes that his doctor’s note simply reads “I don’t know, the vibes askew,” before narrating a chaotic night where characters chase money and momentary relief. The writing brims with paradoxes: on “Potemkin Village Voice” he declares, “Simple man/complicated needs… I’m gonna take the inanimate and make it bleed,” then flips the line to acknowledge his own contradictions. These details turn the record into a travelogue of midlife doubt that never stops rhyming long enough to wallow. — Phil

Kojey Radical, Don’t Look Down

Having made a splash with Reason to Smile, Kojey Radical now takes more inward turns; this follow-up is less about gloss, more about fissures. He began with reflections: spoken-word prologues, reckoning with grief (“How many homies didn’t make it?”), parenthood, identity, public image. He’s still the poet-rapper, but here the narration is more continuous, more panoramic. If you’re a fan of Radical, you know he leans into sample-rich textures, jazz inflections, symphonic soul touches—songs aren’t just beats plus verse but atmospheres you step into. There aren’t obvious radio hits, but each track feels necessary, revealing parts of the emotional scaffold, with pressure, doubt, and the longing for honesty. This breadth is evident in the music (featuring Ghetts, Bawo, MNEK, Dende, and James Vickery), which draws on golden-age hip-hop, disco, grime, indie, jazz, and ska to create a shifting sonic landscape. In interviews, he explains that he wants to be transparent about his flaws so fans can trust him, as he struggles with pride, pressure, ambition, and exhaustion. Within UK rap/progressive hip-hop, Don’t Look Down stakes a claim for patience: for letting songs marinate; for letting any music fan slow down and sit with discomfort. It’s one of those albums that rewards absorption, repeated plays, and is perhaps one of his strongest works yet. — Randy

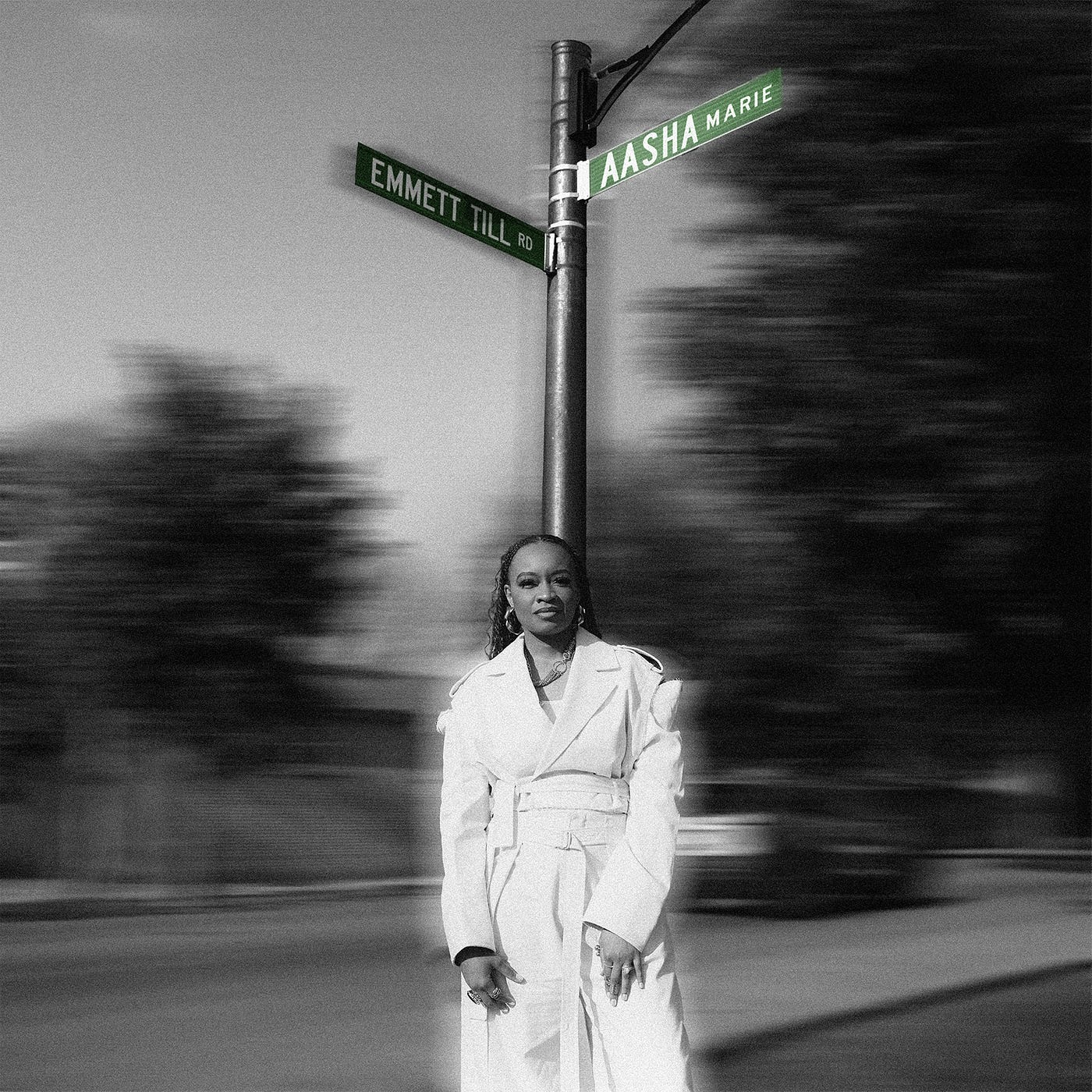

Aasha Marie, Emmett Till Road

Where some artists use debut albums as calling cards, Aasha Marie has written hers as a saga. Emmett Till Road is sprawling by design, a double-disc project that carries twenty-seven songs without apology, each one another stone on the path she’s charting between South Florida upbringing, Chicago grounding, and the spiritual inheritance of Black American history. By invoking Emmett Till, she makes it clear from the start that her music will carry generational weight: this is not just her autobiography, but an offering to the collective memory of those who did not live to tell their own stories. Marie alternates between urgency and meditation—portraits of friends lost, neighborhoods scarred, and romances that flare amid the fire. Church imagery filters through repeatedly, a reminder of the faith she wrestles with and still clings to; it’s not decoration but the backbone of her storytelling. The record ranges from classic boom-bap loops, blues-inflected guitar, gospel-tinged piano, and crisp contemporary drum patterns, which firmly root it in the present. This ensures that the length feels purposeful (like a full-length film), mixing in interludes that bind the narrative and keep us entertained. Emmett Till Road functions as a torch, an album that affirms Aasha Marie’s commitment to using her art as an archive, a form of resistance, and an invitation. As lengthy as it is, she has chosen to stretch her canvas, and it’s something demanding but advantageous, a document you live with rather than skim. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Raekwon, The Emperor’s New Clothes

Raekwon leans into preservation rather than reinvention, and his reverence for classic rap aesthetics informs both the production and the writing. The beats are plush and ornamental, with Swizz Beatz adding orchestral flourishes on the Wu-Massacre “600 School” collaboration and J.U.S.T.I.C.E. League layering glossy soul touches across the record, yet the mood remains conservative boom‑bap rather than anything experimental. “Bear Hill” glides on a lounge‑style loop, while “Pomogranite” and “Wild Corsicans” dip into chipmunk soul and boom‑bap to eulogise friends lost to violence. Nas lends weight to “The Omerta,” and Westside Gunn, Conway the Machine, and Benny the Butcher add grit—yet the focus never shifts from his measured delivery. Throughout, Raekwon sounds comfortable, not urgent; he prioritizes authenticity and truth over contemporary fashion, and the album’s strength stems from this calm sense of authority rather than any desire to reinvent himself. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Chuck D, Enemy Radio: Radio Armageddon

Chuck D wields his baritone the way Coltrane used sheets of sound—layered, unrelenting, and always aimed at a higher civic purpose. Over breakbeats that crunch like smashed radios and shards of distorted acid-rock guitar, he re-stacks the Bomb Squad’s collage aesthetic into a leaner but no less combustible broadcast that ricochets between scowling funk riffs and proto-punk thrash. Cuts such as “Black Don’t Tread” and “Rogue Runnin’” bolt scratch choruses to thrumming bass, using verses that rage against algorithmic misinformation and voter suppression with the same urgency he once leveled at Reagan-era racism. The latter in particular lashes out at complacency, spitting, “eschewed by many losers still stuck in the matrix/Lack the power of persuasion against this hatred,” a reminder that his militancy has always been tied to piercing analysis. Yet the record is hardly a nostalgia trip: on “New Gens,” he cedes the spotlight to Stetsasonic’s Daddy-O and a chorus of younger MCs, threading old-school mic-command into a rolling drill-adjacent cadence that argues cross-generational solidarity is the new radical gesture. Across the album’s “station breaks,” hard-panned sirens, Black radio idents, and shortwave static create the illusion you’re spinning a dial through the apocalypse—only to land, again and again, on a voice that refuses to yield. — Phil

Wale, Everything Is a Lot

Having spent close to two decades writing from the space between Northwest D.C. and his Nigerian household, Wale borrows the chatter and percussion of go-go, writing verses about his own anxiety, ambition, and pride. After a few quiet years away from full-length releases, Everything Is a Lot reads like him finally saying out loud how heavy that mix has become, as it’s a long check-in on grief, fatherhood, and what success feels like when the early‑career rush is gone. “Conundrum” opens with him replaying a conversation with his child’s mother about moving on, listening to her new husband’s opinion and choosing to agree instead of spinning the moment into another melodrama, which sets the tone for how often he swallows his ego here. “Power and Problems” lays out old emotional damage he still hasn’t shaken, “Belly” turns Soul II Soul’s “Back to Life” into a steady knock he can unpack insecurities over, “Michael Fredo” straps triumphant horns onto verses that sound more doubtful than the beat suggests, and “Watching Us” with Leon Thomas flips Goapele’s “Closer” into something more like a quiet audit of whether he’s actually present with the people who care about him. The samples and guests make it clear the budget has grown, yet he keeps circling the same core worries about how much of his real self to expose in relationships, how long he can keep chasing rap without losing the kid who once just wanted his records on local radio, and whether all the acclaim has made him easier or harder to sit with. — Miles Everette

Cam Be & Neak, A Film Called Black

Chicago filmmaker and musician Cam Be and rapper‑producer Neak conceived A Film Called Black as both a record and a cinematic love letter to Blackness. Their ambition shows immediately. “Life in Black” opens with spoken testimonies from various community members, setting the stage for a project that treats each song as a scene. The duo centers the album in soul, jazz, funk, and gospel textures, and the writing focuses on the everyday complexities of Black life. “Wade in the Water” uses a gospel foundation to link present‑day protests with ancestral resistance, as “EyeWonder – Intro Flip” with Skyzoo interrogates cultural discrimination and excellence. On “King’s Speech,” Add‑2 and Elisa Latrice trade verses about leadership and community over urgent horn arrangements, and the middle section’s “Salutations” and “Buttafly” explore transformation with Motown‑inspired hooks. Later tracks lean toward introspection. “Take7” and “God Complex” confront the systems that stifle creativity and examine the psychological toll of struggle, while “Change” uses lush orchestration to link past innovation with present creativity The theme has broadened into a meditation on collective healing and diasporic connection on “Better” and “Motherland,” with Rashid Hadee, Sam Thousand and a full ensemble lending additional voices. Rather than rely on overt slogans, Cam Be and Neak root the record in everyday observations and poetic narration, creating an album that feels like an audio documentary: grounded in history, attuned to spirituality, and committed to celebrating Black creativity. — Quinn Baptiste

Black Milk & Fat Ray, Food from the Gods

When these longtime Detroit conspirators reunite, the chemistry is immediate: Black Milk’s drums slap with MPC grit but pivot mid-bar into Fender-Rhodes sorcery, while Fat Ray’s baritone slides between hustler parables and mystical asides like a griot who’s read too many sci-fi paperbacks. “Elderberry” filters Detroit’s herbalist folklore through drum fills that ricochet like loose car parts on I-94; Ray brags about plant-based immunity while Milk doubles the snares until they splinter. Danny Brown’s manic squeal on “Just Say No” cracks the album’s granite surface long enough for a laugh before the beat slams shut again, while Guilty Simpson and Bruiser Wolf remind listeners that Detroit storytelling can swing from menace to slapstick in a single bar. Throughout, Milk’s arrangements lean on minor-key Rhodes and blaring horns, evoking his own Dilla tutelage without slipping into pastiche; “Talcum,” with its all-rim-shot funk and bass-guitar stabs, shows how he can still make a three-minute loop feel like a short film. Ray matches that cinematic scope by veering between street reminiscence (“stashing in the walls like Jerome”) and metaphysical detours (“spirits in the griot”), delivered in cadences that drag consonants the way a carpenter drags nails across wood. — Harry Brown

Blu & August Fanon, Forty

Instead of basking in nostalgia, Blu marks his fortieth year by curating a series of meditations with producer August Fanon. The Los Angeles rapper has spent nearly two decades narrating the everyday lives of his city, yet this project feels like a birthday card scribbled in quiet rooms. Over August Fanon’s warm, drum-less loops he reflects on fatherhood, friends lost, and the pressure of longevity. Mid-album, “Love (1-4)” runs nearly eight minutes, fluttering through four pocket-grooves while female vocalists stack harmonies like 1970s Roy Ayers sessions; the hook on “Big Picture” likens life to being stuck in a flash-photography row, and elsewhere he raps about the price of art and the distance between faith and fame. At forty, Blu doesn’t reinvent himself so much as take stock. The album’s pleasures lie in his everyday phrasing—quick notes about buying groceries, teaching his children patience, slipping into a memory of his grandmother’s house—delivered in a tone that suggests he’s rapping for himself first. Without relying on bloated listing, Blu and August Fanon craft a comfortable yet earnest album about growing older and choosing gratitude. — Harry Brown

Saba & No ID, From the Private Collection of Saba and No ID

Saba has spent his career threading vulnerability through lively Chicago storytelling, from the youthful optimism of Bucket List Project to the grief-stricken introspection of Care for Me. His latest project pairs him with veteran producer No ID, who mentored him through sessions that encouraged deeper self-examination. The songs, including the well-written “Big Picture,” he likens navigating fame to being stuck in a darkened theater, rapping, “I guess it’s like I’m in a show, sittin’ in a flash photography forbidden row,” a striking image of watching life unfold while the camera is turned off. Throughout the record, he meditates on the price of artistry and the emotional cost of staying present; one track frames painting as an apt metaphor for commitment, another chronicles the weight of expectations when your words are taken as gospel. Without relying on dramatic flourishes, Saba’s writing lays bare his anxieties and growth, leaving the collection as much a self-portrait as a collaboration. — Phil

JID, God Does Like Ugly

A restless debut that put him on Dreamville’s map, a tougher sequel that sharpened his swing, and a sprawling family chronicle that scaled up his ambition. JID’s arc runs from the patient storytelling of The Forever Story to a ferocious reset built on a phrase from his grandmother, and after the summer jolt of “Bodies” with Offset and the scrappy Dollar & A Dream run, he steps into this record hungry and deliberate. On God Does Like Ugly, JID leans into consequence and bravado without losing craft, stacking knotty internal rhymes against hooks that land clean. The belligerent “YouUgly” sets the temperature for a project that pits chest-out boasts against private accounting, while “Glory” and “WRK” compress his precision into chant-ready refrains. “Community” pairs him with Clipse for a street-corner symposium where the writing rotates between watchfulness and confession, JID sketching the politics of favors and debts before Malice and Pusha spiral the language into cautionary parable, “Sk8” bends toward flirtatious release with Ciara and EARTHGANG without softening his grip, “VCRs” snaps into tense, clipped storytelling alongside Vince Staples, while “No Boo” and “Wholeheartedly” test a melodic register that keeps faith with R&B without surrendering the pen. Of Blue” with Mereba becomes a two-voice reckoning that moves from fragility to boundary setting, and the quietest turns feel earned because the record has already done the hard glare from here. The effect is a tougher, funnier writer who cuts the sermon with wry asides, a survivor’s album that reads as earned rather than performative. — Phil

Hit-Boy & The Alchemist, Goldfish

Earlier this year, Hit-Boy broke chains from an 18-year publishing lock just months ago, thanks to Jigga’s nudge through Roc Nation, turning that release into fuel for his first producer-only team-up with The Alchemist who spent decades flipping Mobb Deep classics and Dilated Peoples grit into underground gold before both linked for Goldfish, where their verses swap street survival tales for boardroom boasts and family anchors, each bar etching the grind of starting over with scars as blueprints. “Show Me the Way” hands reins to legacy with The Alchemist watching his son spin records, Hit-Boy’s follow-up boasting “Beat up any beat, press play to see me evolve” amid hidden cracks cops miss and kicks costing thousands that imposters envy, their flows demanding space for Black confidence that shrugs off humble calls for raw want. “Celebration Moments” turns every day into confetti over dead faces on bills, The Alchemist tossing paper while Havoc weighs crown weights and noise tunes, Hit-Boy joining to affirm heavy heads that seize control now without wild distractions. Goldfish swims their paths from locked deals and deep cuts into shared waters where verses voice the reinvention that turns old weights into waves carrying them forward. — Harry Brown

billy woods, Golliwog

When Golliwog opens with “Jumpscare” with warped horns and tape hiss, it sets a claustrophobic mood that never fully lifts. billy woods raps in dense, imagistic bursts, stacking references to colonial history, horror cinema, and everyday micro‑aggressions until the lines feel like overlapping newspaper clippings. Throughout the album, the production pivots between dusty jazz loops and abstract sound design. “Star87” floats over a detuned vibraphone riff that keeps slipping out of key, while “Misery” uses a brittle guitar figure that fractures under heavy reverb. Guest spots amplify the kaleidoscope; Bruiser Wolf’s off‑kilter drawl on “BLK Xmas” adds sardonic humor, Despot’s surgical precision on “Corinthians” sharpens the track’s edges, and ELUCID appears multiple times, his voice acting as both mirror and foil to woods’ weary baritone. The middle stretch (“Waterproof Mascara,” “Counterclockwise,” “Pitchforks & Halos”) digs into paranoia, with drums that drop out unexpectedly, forcing the listener to cling to woods’ internal rhythms for footing. Near the end, “Lead Paint Test” and “Dislocated” widen the sonic palette with industrial clangs and ghost‑choir samples, pushing the project into near‑apocalyptic territory. Despite the heavy subject matter, there is a sly playfulness in woods’ rhyme schemes; multisyllabic patterns tumble into sudden blunt phrases, mirroring the album’s thematic tension between performance and painful memory. — Phil

Ray Vaughn, The Good The Bad The Dollar Menu

Ray Vaughn doesn’t hide behind bravado on his Top Dawg Entertainment debut. He raps from the perspective of a kid who has survived poverty and wants to tell the truth about it. The opening skit ends with the piano-laden “Flocker’s Remorse,” where he recalls, “Phone disconnected, God then went AWOL/The same time I seen my stepdaddy hit an eight-ball… Had to split a six-piece nugget with my motherfuckin’ kids,” framing fast food as both salvation and symptom. Later on, he flexes with West Coast humor, bragging, “CJ from GTA taught me to drive… Big Worm should’ve shot Craig, yeah/And blame it on Kanye meds” and admitting he’s “scared of nothing but my mama belt and that DA.” The tape’s emotional core comes on “Flat Shasta,” where Vaughn raps about his mother’s struggles with schizophrenia: “If you lose all your marbles, you ain’t gon’ have none to play with/A Black woman who crying for help and I’m tryna save her,” later begging her, “Can I borrow one of your laughs, and can I steal one of your smiles?… If it wasn’t for your womb, I wouldn’t be breathing right now.” Even when he celebrates, like on the playful “Dollar Menu,” he undercuts the flex by remembering he once had “sleep for dinner” and that people beg in DMs while he “feeds off the dollar menu.” By the time he reaches the Bay Area anthem “Look @ God” and the confessional “Janky Moral Compass,” the project has covered hustles, mental health, and maternal love without losing its charisma. It is a coming-of-age story disguised as a mixtape, as vivid and real as the Long Beach streets Vaughn describes. — Nehemiah

Ghais Guevara, Goyard Ibn Said

Structured in two acts, Guevara’s concept piece follows a fictional anti-hero who rises from corner rap star to luxury-brand demigod before watching the spoils curdle. Act I’s centerpiece “The Old Guard Is Dead” pairs roiling trap drum-programming with a compressed soul sample that sounds like vinyl spun backwards; Guevara rips through double-time boasts only to undercut them with “Aim for the moon, rose from the gallows”—a couplet that frames triumph as execution by another name. Act II flips the palette: “Leprosy” slows the tempo, substituting hazy guitar chops while he sneers, “actions don’t match their lyrics,” a self-indictment as much as industry critique. Throughout, his flows dart between Philly street punchlines and West African griot cadence, a nod to the historical Ibn Said, whose name he borrows. By finale “I Gazed Upon the Trap with Ambition,” the beats have thinned to skeletal clicks, and Guevara’s voice fractures into half-sung laments, the anti-hero finally staring into luxury’s hollow center. The narrative gambit never feels forced because Guevara’s technical fireworks—polysyllabic rhyme chains, sudden meter shifts—keep the story wired to the adrenal rush of outstanding rap records. — Brandon O’Sullivan

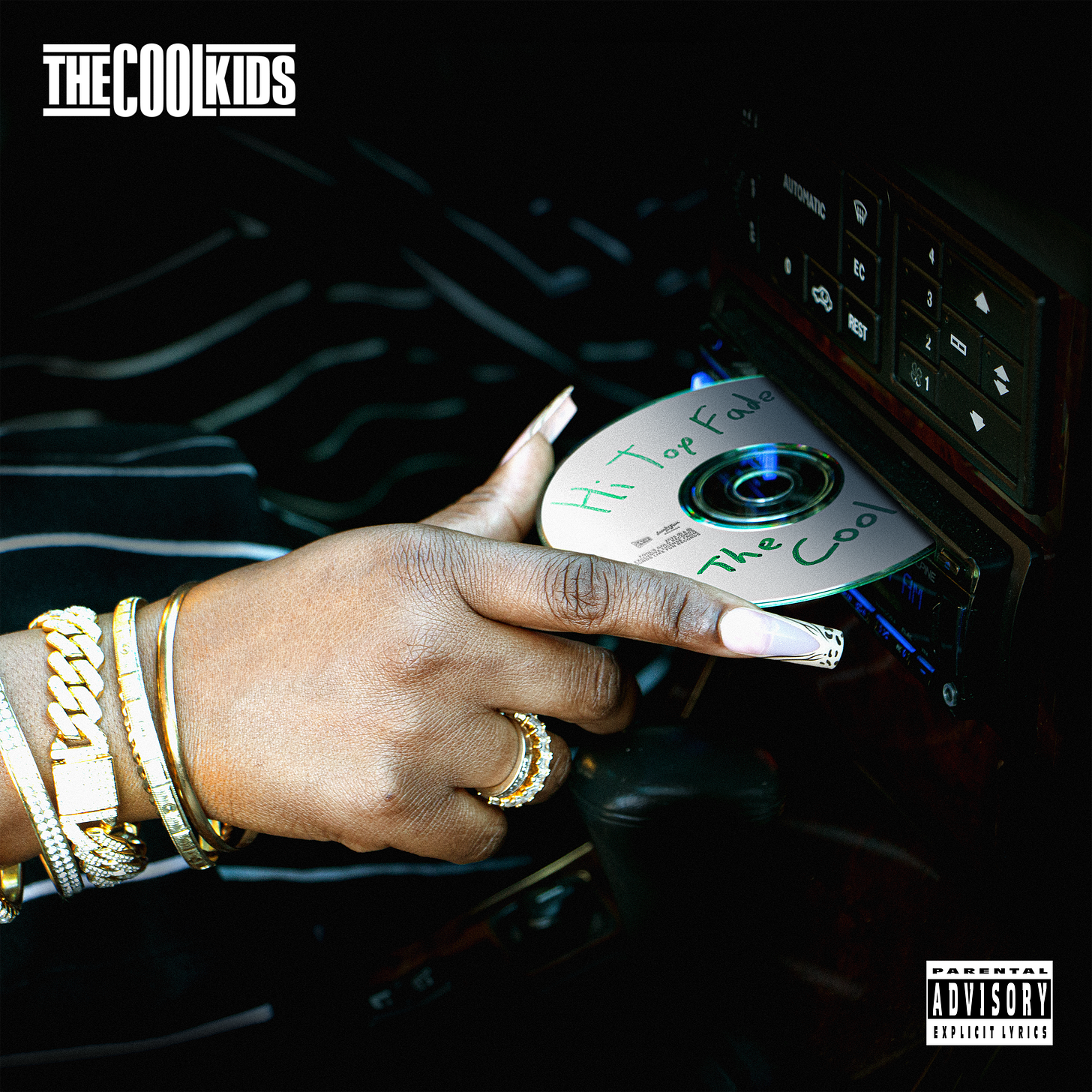

The Cool Kids, Hi-Top Fade

Oftentimes, we never give certain artists their just due for their contributions in their respective eras. The same can be said of Mikey Rocks and Chuck Inglish; they seem to always have felt like one of the very timeless duos in rap. When they release an album, it never fails, and with this effort, in particular, it hits differently when you are driving around. On the record, they start with straight bars on the song “Cigarello Helmets,” then reach back into the past with songs such as “Rockbox” and “Foil Bass,” and blend the nostalgic samples seamlessly in the song “95 South.” In addition to that, guest appearances of Seafood Sam, Radamiz, and Jess Connelly give the album its fair share of surprises. Even the cover is quite well set to craft the tone, as there is a moment when, as soon as the first track will be played, you will be swept to that old-school relaxed feeling, the feeling that will send you right down the memory lane. In essence, you will find everything that you like about The Cool Kids right here on Hi-Top Fade. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Wretch 32, Home?

After decades spent reminding those that British rap carries histories deeper than charts, Wretch 32 pivots toward a softer, more reflective register on Home?. Gone are the fiery freestyles of his early years. He builds the record around the dual yearning of diasporic belonging and London exhaustion. On “Nesta Marley,” he borrows Dido’s melody to make a pointed observation about U.K. multiracial life, rapping, “Roots and culture in my system, di I-dem big and strong/People fighting out my window, cyant they see da sun?” That tension—between inherited pride and contemporary alienation—runs through the album. The interlude “Home Is Where The Heart Is” turns an old platitude into something interrogative, asking, “They call me all of the names, under the sun, still I rise, morning come/Home is where the heart is, why do you stay where you are?” The record’s high point arrives when Wretch and Little Simz trade verses on “Black and British.” It grounds the project in his family’s Windrush legacy as he recalls a grandmother who came to the U.K. “to build a future… But the road weren’t paved with gold, it was paved with ‘go home.’” By foregrounding everyday speech and intergenerational memory, Wretch writes himself into a lineage without preaching. Home? is a question and an invitation to imagine a community that exists beyond border policing and assimilation. — Ameenah Laquita

Loyle Carner, Hopefully !

Loyle Carner turns away from community narratives and toward domestic life as a father, as his voice is low and conversational, sometimes even humming. He mixes rap and a previously unused croon with his singing voice, which emerges naturally and unforced. He speaks about the weight of being a parent, confessing doubt: “They said my son needs a father, not a rapper,” and “this fear in my belly” during early fatherhood moments. Where his Mercury-nominated Hugo wrestled with racial identity and paternal absence, Hopefully ! turns its attention to the immediate intimacies of fatherhood, partnership, and self-doubt. On the title track, he admits his faith in other people is aspirational: “You give me hope in humankind, but are humans kind?/I don’t know, but I hope so.” That ambivalence runs through the record. On “About Time,” he recounts an argument with his partner and confesses “another fucking thing I know you couldn’t forgive”; later, on “Lyin,” he describes himself as “just a man trained to kill, to love I never had the skill,” couching his fear of emotional ineptitude in the language of soldiering. Carner balances these heavy admissions with domestic snapshots: “All I Need” revisits his mother’s house, where the smell of “the sheets on my mother’s mattress” reminds him of learning backflips, and “Lyin” strings together surreal images of early parenthood, including a bedroom wall that falls “to Poseidon” and the feeling of a child’s hand tightening around his finger. Producer Avi Barath coaxes Carner into singing more than ever, and his low, unaffected croon cuts through the album’s sweetness like lemon juice. This feels like a journal of familial love and parental uncertainty delivered calmly but with care. — Murffey Zavier

Nick Grant, I Took It Personal

Nick Grant documents his experiences in the industry and his motivation to assert artistic autonomy, refusing bombast while maintaining technical precision. He alternates between soulful boom-bap and more ominous trap-inflected beats, shifting from proclamations of lyrical supremacy to autobiographical reckonings. On his fourth full-length, I Took It Personal, he bears the weight of those experiences with both pride and anger. In “Let It Reign/Read Your Contract,” he rails against major-label disappointments and cautions aspiring artists, balancing confidence with caution. He explores love on tracks like “Do You Love Me?” where devotion becomes ambition’s fuel, then pivots toward asserting dominance over his underdog narrative on “Big Tymers.” He speaks on street authenticity and competition in pieces like “Love for the Mob” and “Product, User, Dealer,” weaving vivid stories with calm but forceful delivery. In “Nothing’s Free,” he reflects on systemic struggle over darker piano chords. Grant uses his craft to process personal and professional trials without resorting to sentimentality. He asserts himself not just as a rapper but as a figure shaped by industry trials and street tales. Grant uses industry jargon, family confessions, and witty wordplay not as disparate flexes but as evidence that he’s grown from the ambitious newcomer of ’88 into a seasoned observer who refuses to be exploited—he truly took every slight and triumph personal and turned them into art. — Harry Brown

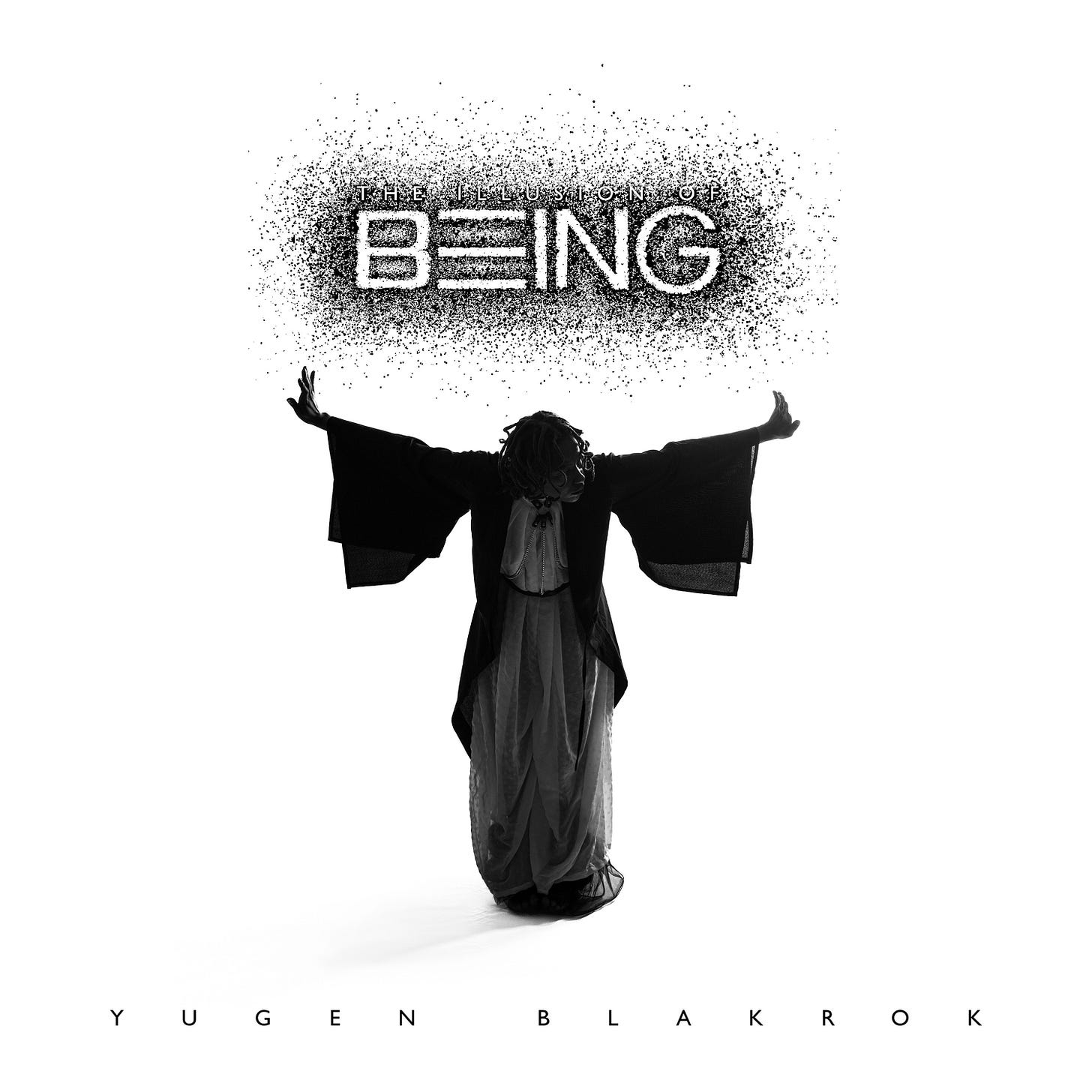

Yugen Blakrok, The Illusion of Being

South African rapper Yugen Blakrok crafts science-fiction hip hop that feels both ancient and futuristic. With her long-awaited The Illusion of Being, it’s her most meditative journey yet. Written largely in solitude in the Catalonian mountains, the album explores spiritual wars and Afrofuturist mysticism. On “Tessellator,” she chants, “Creation and destruction, I am the one after that/In thought, form and function, I am the one after that,” affirming herself as a force beyond binary oppositions. The mantra captures the album’s theme: being is not static but a constant oscillation between building and dissolving. Blakrok’s dense alliteration and mythic references saturate songs like “Mesmerize” and “Hidden Pillar,” where she raps in measured cadences over Kanif the Jhatmaster’s dusty loops and desert-blown flutes. The presence of guests Sa-Roc and Cambatta on “The Grand Geode” and “Tessellator” adds contrasting energies, yet she remains the gravitational center, her voice calm even when the beats tilt toward chaos. Throughout the record, she swaps anger for contemplation, reflecting in interviews that her relationship with South Africa has evolved and that these songs are “for those waging silent wars within themselves.” The result is a hypnotic, immersive project that functions like a ritual, asking listeners to sit with their own shadows. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Mobb Deep, Infinite

We lost Prodigy a long time ago, and the weight of that loss remains heavy. Havoc (along with Big Noyd) has been the one to keep everything in place, as they put together, yet the mention of Infinite restores all that made Mobb Deep untouchable. This year, more than any other, saw a revival of many pioneers in the hip-hop world as who joined hands with Mass Appeal for its Legend Has It series alongside Nas, Raekwon, Ghostface Killah, and a host of other artists. Whenever Prodigy speaks on a record, you can feel the burden of his art. A finely honed street philosophy, wordplay upgraded to lived experience, that stillness of purpose with which he could turn his empty words into poetry. The production of Havoc on Infinite is very precise, devoid of loudness and over-the-top bass sounds, very convenient bass notes, in the record “Pour Henny,” cool waves of the strings, drums beat your head, but does not declare itself aggressively, in the song, “We the Real Thing,” the bass sounds are very quiet, and the strings are the ones that shine through. It goes well with Alchemist, which adds light to grittiness, therefore keeping the attention on the bars. The album sounds like a time capsule and a tribute, a history of the fact that what Mobb Deep had created was not simply sound, but it was survival art. — Phil

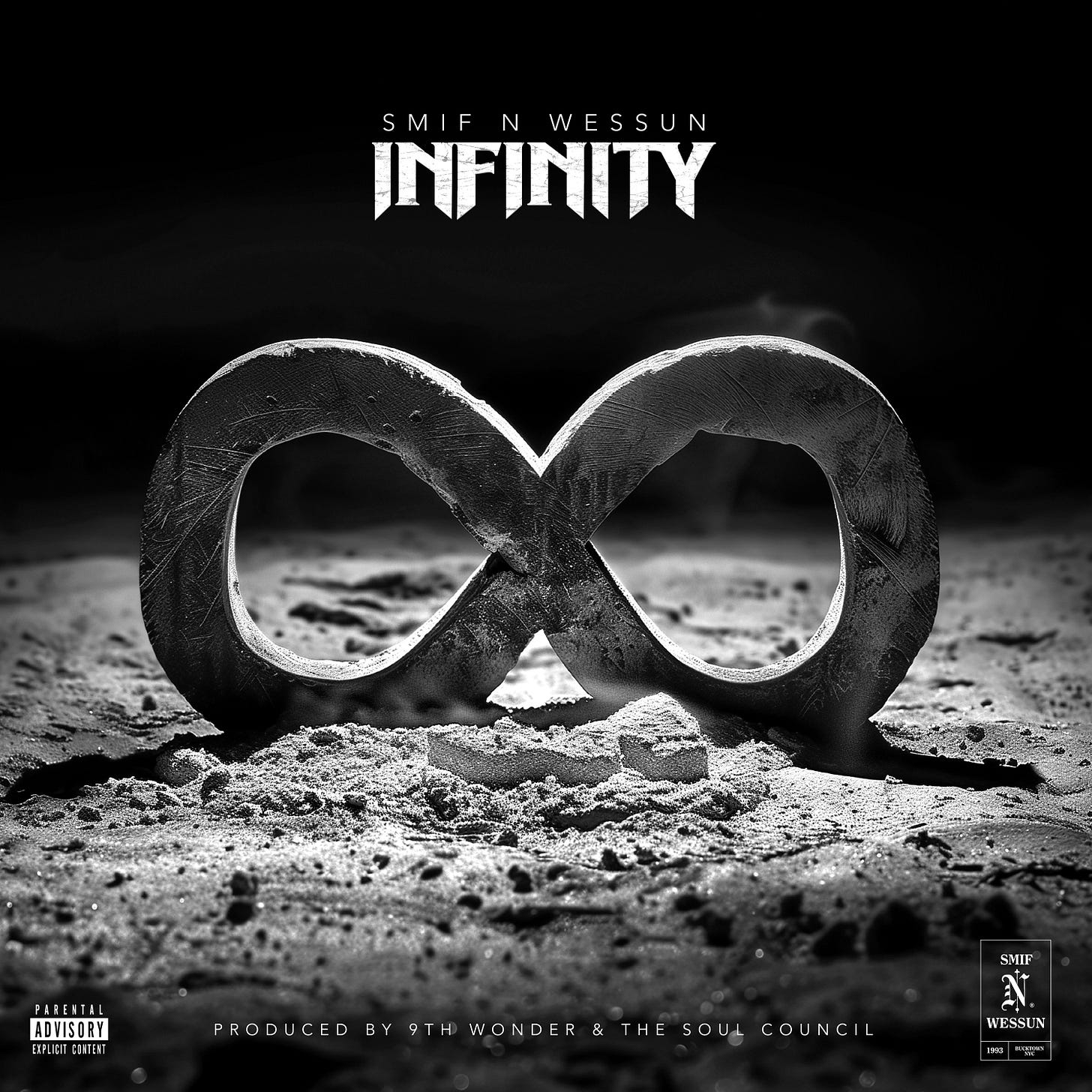

Smif-n-Wessun, Infinity

Brooklyn duo Smif-n-Wessun have survived name changes, label disputes, and decades of New York hip-hop history. Reuniting with Jamla Records, Infinity shows Tek and Steele embracing maturity without losing their competitive edge. The Khrysis-produced title track opens the album with a clear mission statement: “Mic therapy my specialty,” Tek boasts, asserting that his rhymes are both medicine and craft. That self-awareness threads through songs that explore spirituality (“Moses Promise” weighs patience and profits over a vintage soul loop) and intimacy (“Namaste” flips a grown-and-sexy narrative into advice: “To get different results, you gotta do different things”). The duo’s chemistry remains unforced; on “Medina,” they invite Pharoahe Monch to stretch language, and on “Black Eminence,” they honor the late Prodigy with hushed reverence. Even when the beats drift into psychedelic territory, as on “Beautiful Trip,” Tek and Steele stay grounded, using each verse to weigh street codes against personal growth. The closing track “Bad Guy” ends with the question “You want the ugly truth or a pretty lie?,” a moment that captures the album’s ethos: these veterans would rather deliver hard wisdom than nostalgia. — LeMarcus

Leikeli47, Lei Keli ft. 47 / For Promotional Use Only

For the past three projects, Leikeli47 built her mystique behind a balaclava, spitting anthems about beauty supply stores and New York streets. She begins a new phase by stepping out without her trademark mask, aiming for direct connection under a title that pokes at industry marketing. “450” sets the agenda as she chants “Badness, mi nuh care” over sparse bass and kick, mixing bravado with patois flair. “Soft Serve” flips snack-shop references into a breezy boast that keeps energy light. Across eleven tracks, she moves between rapid-fire bars and catchy hooks without strain. Beat choices favor thick, low-end, and crisp hand claps, placing her voice in clear relief. “Queen” leans on call-and-response chants that stress self-worth. When a dancehall pattern emerges in “Starlight,” the vocal tone shifts to a warning mode, showcasing range without spectacle. Patois phrases and East Coast slang ground her perspective. The decision to appear without her trademark mask aligns with lyrics that trade concealment for straightforward testimony. Lei Keli ft. 47 / For Promotional Use Only captures her versatility while keeping confidence front and center. — Jamila W.

Clipse, Let God Sort Em Out

After sixteen years of silence, the Thornton brothers step back into the same room and decide that nothing about the Virginia they once painted has become prettier. The beats arrive almost entirely from Pharrell, stripped of the starry-eyed chrome that once glittered on Hell Hath No Fury and replaced by something colder, closer to bone. Guitars sound like rust flaking off abandoned cranes (thank you, Lenny Kravitz), drums hit like someone counting losses, and the basslines sway like faulty streetlights. Over this skeletal landscape, Pusha and Malice trade verses that feel like depositions and confessions taped on the same cassette. They mourn parents on the opener, recounting funerals where “the birds don’t sing, they screech in pain” while John Legend’s choir levitates behind them like remembered hymns. Kendrick arrives on “Chains & Whips” and the two camps swap parables about ownership, each syllable measured in shackles and stock options. Tyler brings cartoon menace to “P.O.V.”, Nas closes the record with a eulogy for the block that raised them all, and through every cameo, the brothers remain the eye of the storm—precise, unhurried, speaking of dope still hidden in baby pictures and of brothers who became cautionary tales before they turned twenty-five. There is no fat, no victory lap, only the sound of two men weighing every dollar, every body, every prayer against the scale of their own survival. — Phil

Nas & DJ Premier, Light-Years

First announced plans for a collaborative album in 2006 during a Scratch Magazine interview, Nas and Preem spent the next two decades working on the project off and on while focusing on other ventures. Their partnership began in 1994 when Premier produced three era-defining cuts on Illmatic—“N.Y. State of Mind,” “Memory Lane,” and “Represent”—establishing chemistry that became written into hip-hop’s DNA. They continued collaborating on “I Gave You Power,” “Nas Is Like,” “2nd Childhood,” and “N.Y. State of Mind Pt. II,” each track living in a class of its own as blueprint for timeless rap combining raw storytelling, razor-sharp lyricism, and production connected to New York pavement. After all these years of teasing, it felt right to end the year during the Mass Appeal campaign. Premier handles all production across the album, his signature scratch-laden instrumentals veering between throwback and timeless through “Writers,” which conjures the spirit of graffiti’s glory days, while “Nasty Esco Nasir” revisits Nas’s rap personas through an existential run-through. “GiT Ready” and “Welcome to the Underground” find Nas referencing crypto portfolios and Saudi investments, reflections of the artist as contemporary businessman, intermittently nodding to his origins as a NYCHA project kid. These references sit exceedingly far from those found on their initial studio collaborations three decades ago. “It’s Time” repurposes seminal mid-70s funk-rock, leaving “3rd Childhood” elevating the lost art of elite boom-bap, Premier’s unapologetically deep crates combining with Nas’s extensive book of rhymes to set Light-Years apart in their storied catalogs. — Rafael Greene

John Glacier, Like a Ribbon

Between 2020 and 2021, John Glacier forged a distinctive voice amid an era of lockdowns. The album’s producers—Flume, Evilgiane, Kwes Darko, Andrew Aged, Harrison, Zack Sekoff—warp drums until they flicker like faulty streetlights, leaving Glacier’s voice to drift in and out of focus. She opens “Satellites” mumbling through reverb haze, syllables slicing the mix like paper cuts before a sudden bass surge resets the pulse. The record’s emotional anchor is “Ocean Steppin’,” where she raps, “Ocean steppin’ on shores/Crash the wave, then I pause/Bring it back to the land,” turning seascape imagery into a metaphor for psychic ebb and flow. That push-and-pull defines the sequencing: “Money Shows” smears Eartheater’s spectral co-lead across trap triple-hi-hats, then “Found” drapes half-remembered piano over clipped jungle breaks. Glacier’s deadpan delivery disguises barbed confessionals—references to “sleeping in the park ’cause the rent made no sense” land like passing thoughts, all the more devastating for their casual tone. Observers of her live sets describe the record as split into movements that mirror the ways a ribbon curls, falls and snaps back, and that metaphor tracks: energy coils tightly on “Nevasure,” slackens into ambient murmur on “Steady As I Am,” then whips up into break-beat turbulence on “Home” before settling into the whispered finale “Heavens Sent.” — Nehemiah

Earl Sweatshirt, Live Laugh Love

Earl’s path runs from the left-field sharpness of Doris through the inward focus of I Don’t Like Shit…, the fractured diary of Some Rap Songs, and the cryptic sparring of Voir Dire with Alchemist; the new record builds on that history while facing forward. The rollout leaned into mischief, but the songs are serious in their own way, sketching responsibility and doubt in brief scenes. “Tourmaline” holds one of the album’s clearest statements—“Struggle not a team sport”—and a line that places his priorities where they live now: “Keep my feet grounded for my sweet child.” “Live” walks the edge between defiance and exhaustion without reaching for a big thesis. “Infatuation” snaps phrases into place fast, more collage than lecture, and “Crisco” works as a broken-story monologue rather than a puzzle to decode. He keeps one eye on joy without pretending it cancels anything. In “Gamma (Need the <3)” he nods to Roy Ayers with a quick sun-reference, a small opening in an otherwise wary set. Around them sit titles that tell you the framing without overexplaining—“GSW vs Sac,” “WELL DONE!,” “Static,” “Heavy Metal aka Ejecto Seato!”—and the writing stays economical all the way through, which is the point. The record’s charge comes from how little he wastes. He marks fatherhood and pressure in clipped lines, lets the jokes and threats sit next to each other, and keeps the perspective tight enough that any warmth feels earned. — Nehemiah

Sækyi, Lost in America

Chicago’s Sækyi transforms the specific loneliness of cultural displacement into some of the year’s most compelling hip-hop on Lost in America. As both producer and rapper, he creates these cinematic soundscapes that swing with jazz-influenced samples while hitting hard enough to satisfy heads who need their beats to knock. The title track is a confession, with Sækyi opening with the raw admission that he’s “lost in a stolen land son of a broken man” over production that mirrors his fractured mental state. His vocals shift seamlessly between sung melodies and rapid-fire verses, his delivery always matching the emotional terrain of each song as he navigates what it means to be someone who doesn’t fit the prescribed categories of America. He gravitates toward loops that feel like movie scenes, building atmospheres that support rather than overwhelm his storytelling about family trauma and cultural disconnect. His writing avoids easy answers about identity and belonging, instead presenting questions that resonate far beyond his specific experience as someone caught between cultures, examining how generational pain gets passed down through immigrant families. What’s remarkable is how Sækyi manages to create music about feeling lost that provides direction for those dealing with displacement, turning personal confusion into universal understanding. — Brandon O’Sullivan

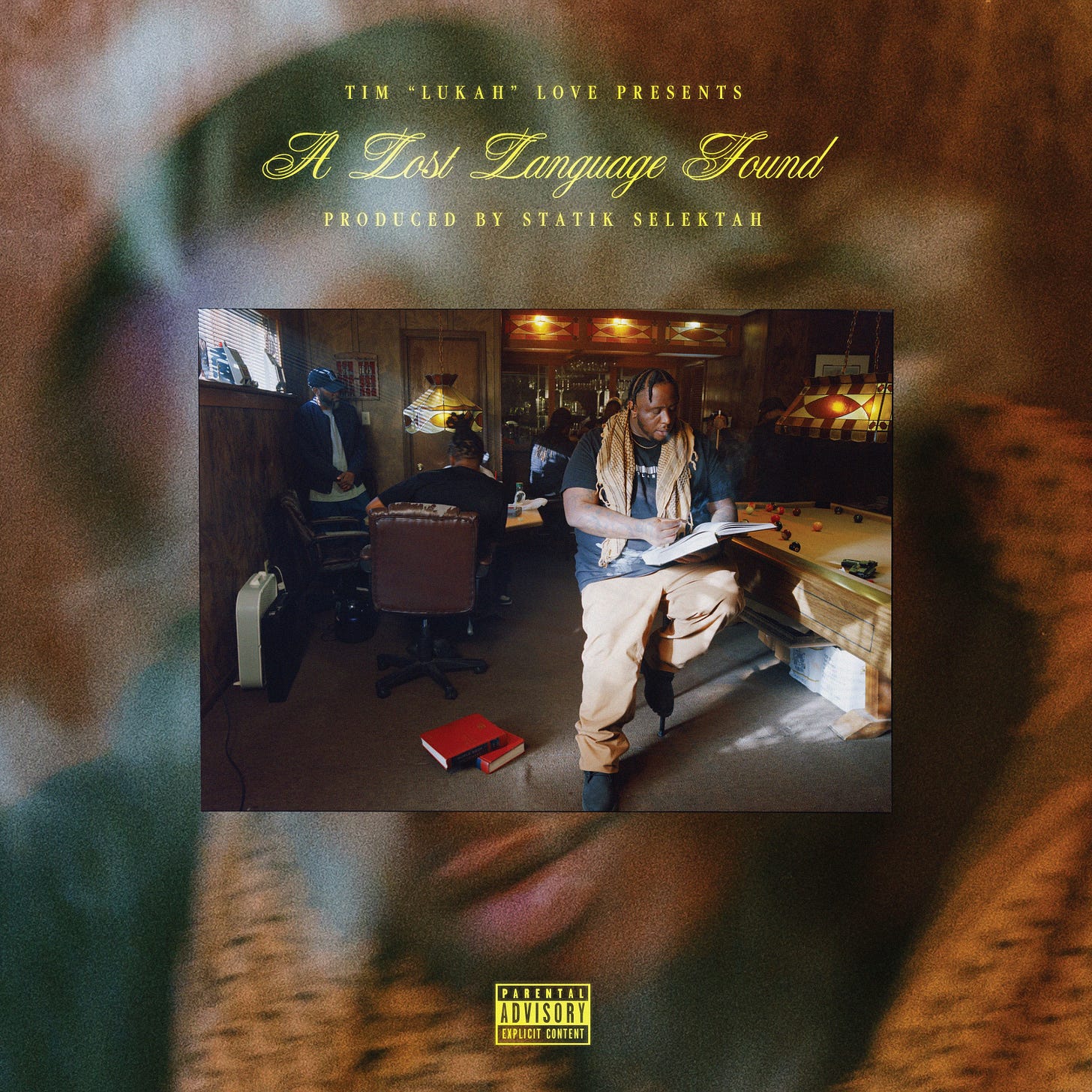

Lukah & Statik Selektah, A Lost Language Found

The pairing of Memphis rapper Lukah and Boston producer Statik Selektah might look unlikely on paper. But knowing their strengths, this was long overdue. Their concept album builds a bridge between regions by treating language itself as subject and instrument. The project opens with “Words Drenched in Acid,” where a sample about American dialect leads into boom-bap drums and distorted guitar while Lukah unspools multisyllabic rhymes as if they were linguistic exercises. The record moves from history lesson to noir-tinged crime narrative—Broadcasting recounts street stories over cinematic beats—and pauses for introspection. “Mirror Discussions” is built on a dialogue sample about colorism before Lukah raps about feeling set apart growing up. Later, “Native Tongues” examines code-switching, and “Shredded Speech” brings veteran Bun B to bridge generations. The album ends with “Power Dialogue,” where a gospel choir replaces spoken-word skits, suggesting healing through communal voices. Without leaning on hooks or easy nostalgia, the duo craft an album of language experiments and regional dialogues. Lukah’s dense verses and Statik’s sample-heavy production show that there’s no single way to speak hip-hop, and that finding lost languages means honoring both tradition and invention. — Randy

Little Simz, Lotus

Since GREY Area, Little Simz has spent half a decade proving that personal excavation can be just as thrilling as bravado. Coming off the inward grandeur of Sometimes I Might Be Introvert and the brisk defiance of No Thank You, her latest project feels like a meditation on the trust she’s lost and the resolve she’s gained. She opens with a bold statement of renewal, trading dense orchestral flourishes for leaner funk guitar and restless live drums engineered by producer Miles Clinton James, her first studio partner since parting with her long-time collaborator. But first, “Flood,” opens with a firm reproach—“How dare you, how dare you/I was shutting down the world, and it scared you”—before guest vocalist Obongjayar flips the scene, humming through a prayer that keeps him “away from the devil’s palm” while still declaring himself “the light.” That tension between exposure and self-preservation informs the record: in “Thief,” she admits that a person she’s known her whole life (*ahem* Inflo) can still appear “like the devil in disguise,” and later she wonders, over a hush of piano and strings, “How can we sleep when there’s murders in the streets?” Simz tempers these confessions with playful edges. With “Young,” she pokes fun at her coming-of-age fantasies, bragging about “fuck-me-up pumps and a Winehouse quiff” and noting, with a grin, that she speaks “a lot of French—oui oui oui.” Throughout, she enlists trusted collaborators for support—Wretch 32 appears to help mend familial wounds on “Blood,” while the closer “Free” repeats that love remains the only true catalyst for liberation. By the time the record ends, the commandments she listed on “Flood” (never trust an outstretched hand, keep your feelings in check, look after your health) have less to do with paranoia than with preserving a self she’s fought hard to nurture. — Brandon O’Sullivan

McKinley Dixon, Magic, Alive!

In 2023, Richmond-raised storyteller McKinley Dixon made waves with the jazz-rap suite Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!?, and his follow-up Magic, Alive! expands that world into myth. Dixon frames the record as a fable about three children trying to reach a departed friend through the power of music, and the narrative unfolds through communal refrains rather than a linear plot. In the centerpiece “Run, Run, Run Part II,” he admits the burden that history places on him—“The heart is heavy, but it’s never held alone/Then keep it steady and you’ll find your way home”—and, just when he seems ready to succumb, a choir swells behind him chanting “We outside, rejoice, rejoice!” Gospel harmonies and horns snake through the album, but Dixon never lets the instrumentation overwhelm the storytelling; “All the Loved Ones (What Would We Do???)” rides a motherly warning that if you don’t behave “my mama said, she gon’ whoop your ass, your ass, your ass,” turning a playground taunt into an affirmation of matriarchal power. He slows down to speak with spirits: “Listen Gentle” is a mournful conversation in which a preacher reassures him that magic can help him “take flight” for one last goodbye, and on the closing “Could’ve Been Different” he addresses a poster of rapper Blu as if it were an ancestor, promising to trust his own talent rather than mimic anyone else. Whether he’s riffing alongside Ghais Guevara and Alfred on the dusty funk of “A Crooked Stick” or letting horns and percussion build into a street-corner celebration, Dixon keeps his eye on the album’s central miracle: that joy, grief, and community can coexist, and that the dead live on through those who sing about them. — Phil

Maxo, Mars Is Electric

Maxo explores new terrain with a laid-back confidence, choosing introspection over swagger in this set of ten tracks. He adopts a pared-down sound palette built around lo‑fi beats, subdued psychedelia, and electronic minimalism that lets his voice settle into the rhythm rather than dominate it. On the lead single, “Human?,” he reflects on human imperfection with the line “God threw us in the world half damaged,” acknowledging vulnerability without dramatizing it. The tone remains experimental and exploratory, while he’s in a mood of searching and emotional honesty. There’s a sense that this album emerged without preset expectations—Maxo himself said he “didn’t approach things so seriously,” and that mindset is audible here. He touches on fractured relationships and loss of innocence in a straightforward, unguarded way. The arrangements shift subtly, layering electronic flourishes and stripped-back drums under his soft-spoken delivery. It’s less about a polished presentation and more about a believable emotional exchange. This is Maxo at a point where experimentation feels natural, not forced. The record suggests autonomy is less about grandeur than about editing until only the honest parts remain. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Armand Hammer & The Alchemist, Mercy

In a rap landscape often dominated by predictable narratives and glossy production, Armand Hammer and The Alchemist choose the opposite path. That of depth, with their second collaborative album, Mercy, which is not an album to be listened to distractedly, but a dense and layered work. When reality can no longer be ignored, the only choice is to face it. Alan the Chemist, who has crafted countless underground rap classics, delivers a colder and more precise sonic performance here than ever before. The instrumentals leave behind the light, jazzy samples, immersing themselves in sustained piano loops, nervous percussion, and sounds that march forward like funeral dirges. A perfect backdrop for billy woods and ELUCID’s vocals, which recite tales of environmental violence, loneliness, and systems that push for surrender. Global conflicts, artificial intelligence, and swarms of news: all of this runs through woods and ELUCID’s verses like a common thread linking personal stories to geopolitical issues. Mercy is a gaze, not an escape. Not an easy redemption, but a work that fills the space left between the cracks of the world. — Koda Lin

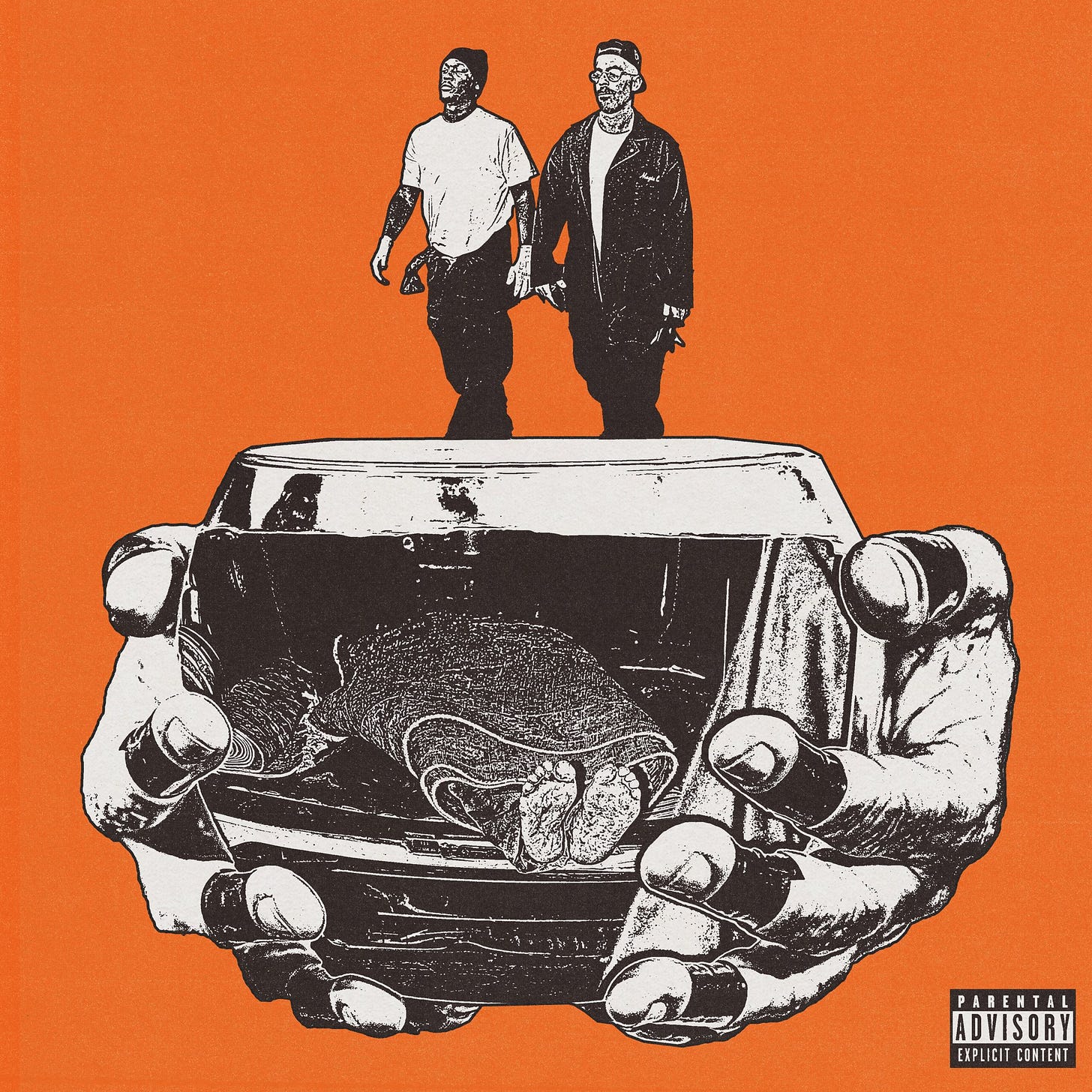

Mick Jenkins & EMIL, A Murder of Crows

The dropping of Mick Jenkins sparked interest in the rap community sector. His pen is a weapon, full of coded language, metaphors of water, and allusions that turn in on themselves. It is the best reminder he could have with A Murder of Crows. He has remained a source of pride for rap fans who value depth, but this project feels like a love letter to the craft itself. The album was recorded front-to-back by EMIL and maintains a consistent, connected energy, beat breathing, verse cutting, and idea slow. The difference between Mick and others is that he feels purposeful. He raps as though he were erecting something we should go back to, not immediately, but forever. All the metaphors, all the beats, are created to relate, to get you thinking. Albums such as this are reminding us that MCing as an art is not dead, and there is still much to learn about it and make it advance. A Murder of Crows has earned its due celebration, for its language, its balance, and what it provides to the culture. — Harry Brown

Open Mike Eagle, Neighborhood Gods Unlimited

Beats from Kenny Segal, Exile, and Open Mike Eagle himself smear soul samples, broken synths, and found audio into a soundscape that feels like walking past thirteen front porches, each one hosting its tiny orchestra. He returns to the concept album with Neighborhood Gods Unlimited as if it were a half-remembered dream he’s ready to finish. The neighborhood in question is both his native Chicago and any place where corner stores sell loosies and memories for a dollar. Gods appear in small forms: a barber who claims he once cut Common’s hair, a cashier who speaks in Gil Scott fragments, a kid on a BMX who swears he can outrun the surveillance drones. Mike narrates with the resigned awe of someone who has seen every miracle downgraded to rumor yet still wants to believe. On “Lease Agreement With the Universe,” he raps about gentrification as a divine contract printed in vanishing ink, while “Argue With the DJ” turns a skipped 45 into a theological debate between fate and free will. — Harry Brown

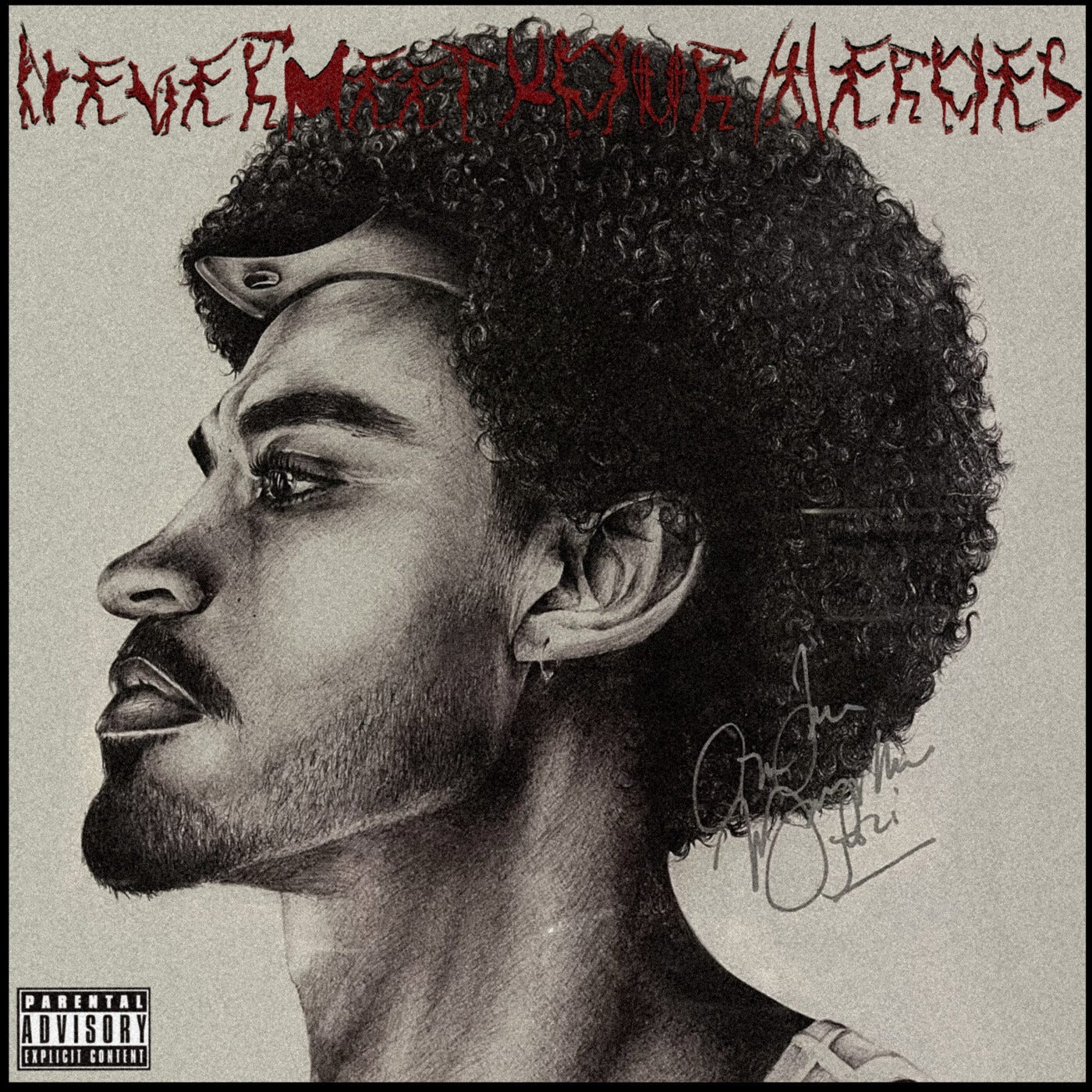

Shane Eagle, Never Meet Your Heroes

Growing up in Johannesburg’s Rabie Ridge, Shane Eagle has always walked the line between township roots and global reach, between faith and street bristle. He comes from a space where ambition meets contradiction. On Never Meet Your Heroes, he steps into a zone of reckoning—of confronting his ideals, his lineage, the pedestal of influence—and plants his mic in that friction rather than avoiding it. The album operates through two clear moves. First, it places Eagle in dialogue with identity, as Son of Yahweh” and “Let There Be Light” signal something spiritual, something that stretches beyond rap’s usual terrain. Then he flips into the grit: “Ride Out,” “Lil D.” and “Wolves” suggest danger, expectation, and life under pressure. There are moments where those mechanics show up plainly. In “Outraged,” he loops a string phrase, letting it wrap around his voice like an echo from a chapel, while the lyrics mention ghosts of ideals and the cost of survival. “Cognac & Cigarettes” trades swagger for confession, the beat tight and sparse, letting his verses hang in a hush rather than filling them with noise. And on “My Daughter’s Hand,” he turns vulnerability outward, giving someone else the vision instead of the mic—this move stakes his place differently, not as a lone hero but as a father, witness, human. — Phil

R.A.P. Ferreira & Kenny Segal, The Night Green Side of It

R.A.P. Ferreira has been turning his own life into coursework for a while now. Small labels to run, a custody battle laid bare on the last record, a shifting list of cities and responsibilities, all funneled into a talky, bookish style that still carries a blues weight. Teaming again with Kenny Segal, he arranges this one as the quiet, late chapter of a trilogy that reaches back to So the Flies Don’t Come and Purple Moonlight Pages. At this every‑few‑years summit, the two of them see how far they can push this shared language without losing the everyday details that keep it grounded. Segal builds the setting from live jazz players and crooked loops—Mekala Session’s restless drums, Skyline Electric’s band takes, Aaron Shaw’s tenor sax, Jason Wool and Diego Gaeta on keys, Jordan Katz’s trumpet, extra bass and tape murk stitched underneath—so the beats feel less like a neat grid and more like a small combo learning to follow a sampler instead of a bandleader. Inside that loose frame, “Spicer and I” lets a scrambled piano line finally settle into a strut while Ferreira flips between bragging and self‑correction. Somewhere else, “By the Head” wraps thin strings around a dry drum pattern as he pokes at the question, “Is the language alive?” “Credentials” drops a memory of his grandfather explaining what fatherhood costs, as “Defense Attorney” stacks images of injured children, demons, and his own exhausted empathy into a plea that sounds aimed at a judge and at himself. — Harry Brown

Ché Noir & The Other Guys, No Validation

Buffalo MC Ché Noir has established her artistic identity through an evolving mastery of narrative craft. She has already released two projects this year, and one of them is a sequel. Produced in its entirety by The Other Guys, No Validation extends this trajectory into a more rigorously autobiographical and communally resonant register. The inaugural track, “Incense Burning,” situates itself in quotidian domesticity, layering a subdued soul motif beneath reminiscences of “incense burning and wine and some music,” before receding to formative memories of “a nerdy kid in the hood, watchin’ Dragon Ball Z,” thereby interweaving cultural nostalgia with early entrepreneurial sensibilities. The structural centerpiece, “Katastwof,” features Skyzoo and Ransom, with Ché recounting delayed recognition in the line “a late bloomer in this game, they wouldn’t give me a chance” before reframing herself as “a fertile seed surrounded by the industry plants,” an agrarian metaphor of resilience and belated flourishing. Ransom concludes with reflective counsel: “Can’t add no days to your life, so just add some life to your days.” Three times a charm. — Harry Brown

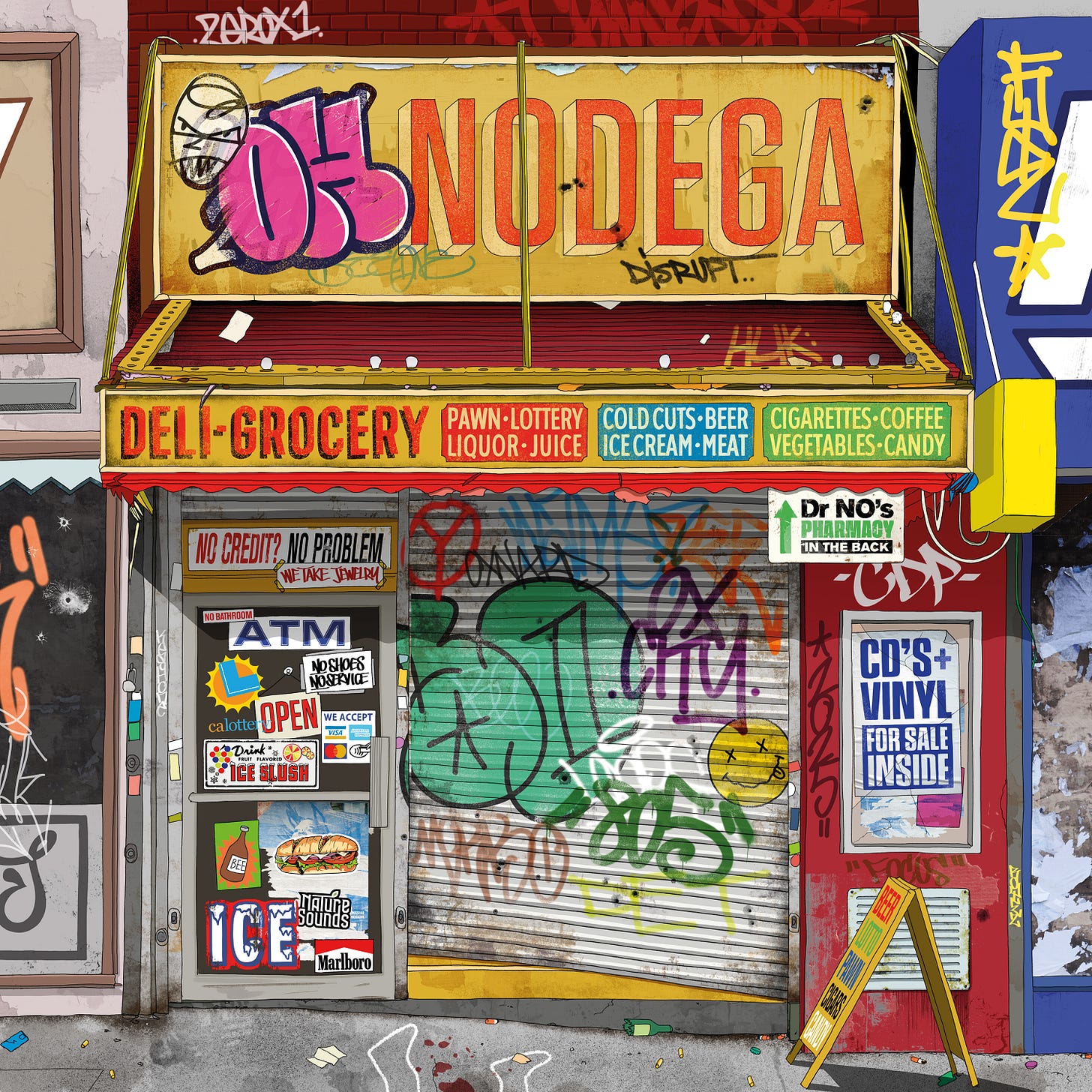

Oh No, Nodega

Where his brother Madlib became hip-hop’s mad scientist, fragmenting soul into abstract collage, Oh No erupted as the visceral counterpoint—his 2004 Stones Throw debut, The Disrupt, announced a producer who could make drums feel like blunt force trauma. But while his sample-based instrumental suites have long explored far-flung sounds, mining Mediterranean psyche-funk on Oxperiment, Roy Ayers’ cosmic jazz catalog, and the dusty corners of Italian library music. Nodegafinds him returning to the bodega’s fluorescent-lit urgency, the corner store as both sanctuary and war zone. The album’s concept materializes as a neighborhood bodega where microphone assassins congregate to document street chronicles, but Oh No’s production transcends simple boom-bap nostalgia. On “Gutter Streams,” he reunites with The Alchemist as Gangrene, their chemistry recalling the paranoid funk of early Mobb Deep. “Nodega Run” employs vibraphones to anchor J. Sands’s storytelling, the rhythmic shimmer evoking Detroit’s most introspective moments. “ICU With Bottle Service” samples what sounds like 16-bit video game warnings, transforming digital arcade menace into street-level threat. The album’s genius lies not in reinvention but in Oh No’s understanding that the corner store, like the drum break, like the sampler itself, remains hip-hop’s most democratic space, where veterans like Ghostface Killah, Rah Digga, and Talib Kweli share oxygen with Tha God Fahim and CRIMEAPPLE, all congregating under flickering lights to testify. — Harry Brown

Backxwash, Only Dust Remains

Zambian-Canadian rapper and producer Backxwash concluded a trilogy of cathartic albums with Only Dust Remains. On the opener “Black Lazarus,” she begins with confession—“I been away from my place of balance/From the lakes that carried my mistakes and challenge”—before a haunting refrain of “Nobody pray for me, nobody’s saving me” repeats like a curse. Her verses blend spiritual imagery with blunt admissions of addiction and despair, asking on “9th Heaven,” “What I was told by angel Gabriel bold/As I’m fresh off a probe that is placed and latched in the skull… Is it worse than not knowing your worth/And your boss calling for work.” Even amid these doubts, she reaches for clarity; on “Stairway to Heaven,” she notes, “Karma’s reaching out for every onus of my soul/Feel the pressure I just need to carry on,” later urging herself, “Do not fear the void/It is not your enemy.” The album’s most searing moment arrives on “History of Violence,” where she ties personal trauma to political oppression, calling out silence around atrocities: “Meet me in afterlife/You can meet me in afterlife… From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” By the time she reaches “Undesirable,” rapping, “I’ve been meaning to say this… Gotta breathe when I say this,” the album feels less like a collection of songs and more like an exorcism. Backxwash offers her rage, sorrow, and hope without euphemism, turning her final chapter into a testament of survival. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Sol.ChYld, ReBirth.Theory