The Additional 30 Best R&B Albums of 2025 (Honorable Mentions)

These R&B records strip away the excess to reveal raw emotion and deft musicianship. From neo-soul meditators to funk-infused groove masters, they prove the genre’s heart still beats strong in 2025.

After unveiling our top selections last week, let’s shine a light on the albums that circled the podium but just missed the spotlight. These records share a restless spirit—artists testing the boundaries of genre, forging unexpected dialogues between voices and writers, and trusting the power of a well-placed melody. Here you’ll find global crosscurrents, late-night revelations, and funk revivals that honor the past while charging into the future. They may not claim gold, but they’re vital chapters in this year’s music story.

Seba Kaapstad, 4ever

A band known for expansive palettes pares the ideas into quick, no-nonsense songs. The multinational quartet still moves like a conversation between voices and writers who know each other well—South Africa’s Zoë Modiga, Eswatini’s Ndumiso Manana, and German partners Sebastian “Seba” Schuster and Philip “Pheel” Scheibel—but this effort here pushes for immediacy, with melodies that land fast and arrangements that leave air for phrasing and harmony to carry the weight. The dialogue between singers stays central, trading pledges and side-eye within compact hooks, while the rhythm section slips in sly breaks and handclaps rather than long builds. “Off Kilter” puts that design under a spotlight, a nimble back-and-forth sharpened by Tank from Tank and the Bangas; the groove snaps to attention then eases off, letting the vocal lines do the nudging. The group settles into warm morning light and quick-cut swing, favoring memorable turns of melody over extended solos. It’s the kind of record that trusts songwriting, not scale, where a through-line of empathy that fits the band’s cross-continental DNA. — Reginald Marcel

Masspike Miles, 11 Highland Ave

Long before he went by Masspike Miles, Miles Wheeler was the teenage singer drafted into Maurice Starr’s boy‑band project Perfect Gentlemen. After the group’s 1993 album flopped, he stuck with music, releasing a string of mixtapes and eventually signing with Maybach Music. The album kicks off with him instructing a partner to “roll up this fat joint and take another hit” before he reflects on childhood determination, acknowledging he is his own worst enemy and that vice and celebration often lead nowhere. He counters these vices with lessons about perseverance, singing “Time changes everything as we grow old/Hold on to love, it’s worth more than gold,” and concludes that wisdom comes at a cost yet still encourages listeners to chase their dreams. In “Caught in Her Love,” he narrates a relationship that feels simultaneously exhilarating and dangerous; he admits to taking full responsibility for initiating it and counts each step, “Two, I was sober, three words, and was ready, fourth call, she came over,” as if trying to pinpoint the moment when infatuation became entanglement. “Bankrupt Millionaires” broadens his focus to critique greed, with verses lamenting that “dirty money only needs a rinse” and singing about being “bankrupt millionaires,” while he emphasizes that “cash rule everything around U.S. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Bootsy Collins, Album of the Year #1 Funkateer

Bootsy’s latest carnival opens with a thunderclap of clavinet, talk-box chatter, and a bass line dirtier than a P-Funk tour bus floor. One moment, he’s dropping a tight “on-the-one” homage in “The JB’s Tribute Pastor P,” weaving Clyde Stubblefield’s drum DNA around rapid-fire rhyme cameos; the next, he’s leaping into “Bubble Pop,” a synth-doused slice of space-disco where his slap bass ricochets off laser-beam guitar licks. Even the zaniest detours—metallic shred workouts, cartoon skits about AI gone rogue—are glued together by that rubbery low-end tone that could only come from the star-shaped Space Bass. Yet beneath the jokes and psychedelic FX is a living history lesson. Bootsy threads gospel shout-outs, G-funk hand-offs, and sly Afro-beat nods into a single revue, treating funk less as a genre and more as an eternal, renewable resource. Guest spots are deployed like fireworks, but Collins remains ringmaster, his bass anchoring each side quest while his falsetto ad-libs remind you fun is sacred business. In doing so, he reasserts why his fingerprint has never faded from modern groove music. — Harry Brown

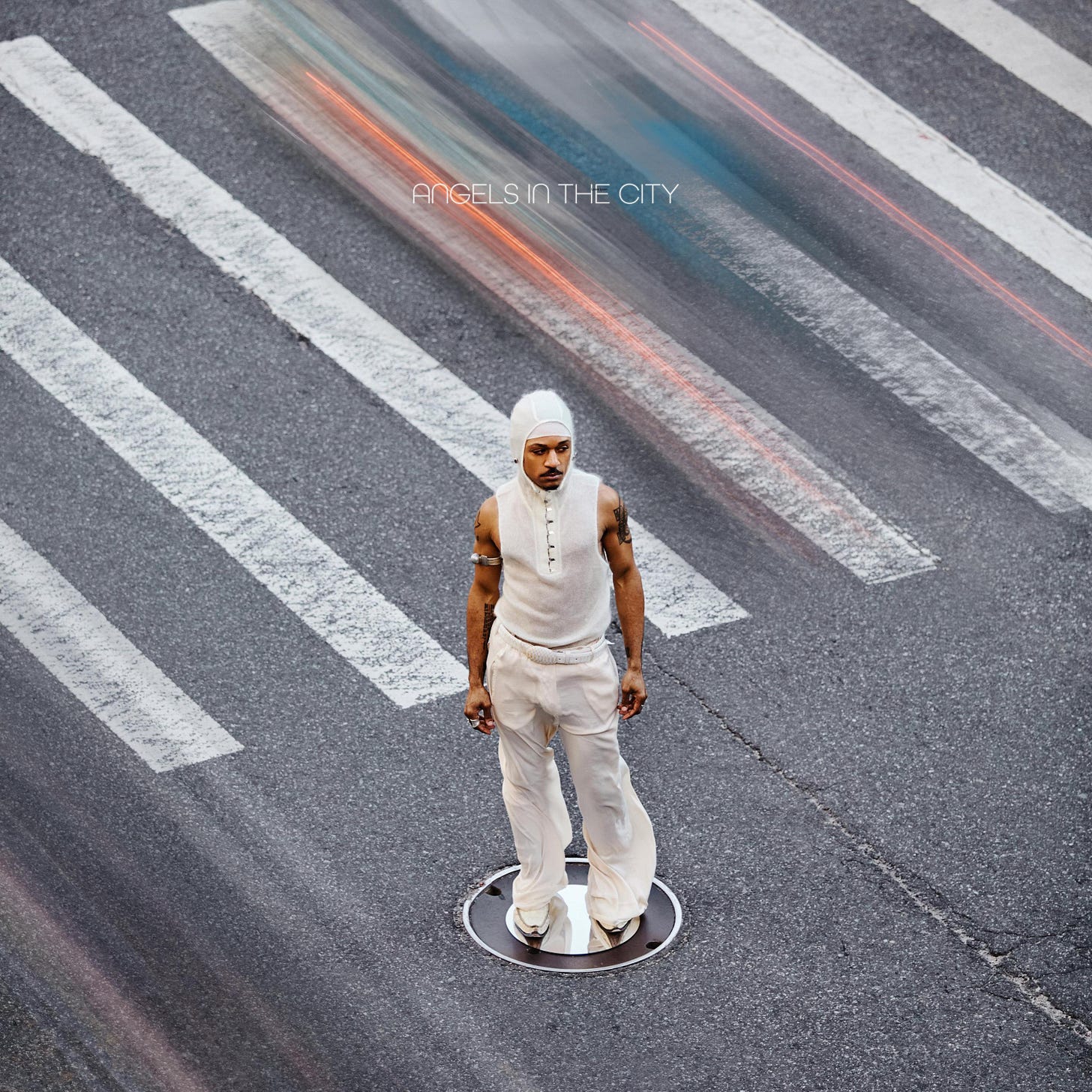

James Bambu, Angels in the City

After a steady climb through self-released projects—Del Sol, Dialogue, PLUSH—James Bambu uses Angels in the City to widen the lens on his alt-R&B palette without abandoning the songwriter’s control that defined those records. The new set moves like a city diary: synth-bright midtempos and glassy ballads where he pressures his tenor into soft confrontations with doubt and desire. You hear him sharpen rhythm writing on “Backseat,” built from a Latrell James beat pack he pulled months before release, then turn to more patient forms on “Be Patient” and “Mulholland,” where the melodies hang long enough to register as motives rather than hooks. The performance film that accompanies the album underlines the project’s self-directed feel—staged, sung, and paced to make the arrangement choices feel lived. The result is continuity with his earlier work (DIY fidelity, careful arranging) but with a more public stance, a story about making room for grace under neon. — Jamila W.

Iman Europe & Kaelin Ellis, Chrysalis

Having moved between rap and R&B since the mixtape Caterpillar, Iman Europe arrives here from limbo, from that in-between space where the self is being stretched by time and observation, and gives Chrysalis as both a confession and an emergence. Growth is the album’s architecture. Europe sheds old skins, stepping out of social media masks, growing wings in private while being watched in public. She digs into transformation in digital era terms—comparison, performance, solitude—and the title track opens with surrender, retreat, longing to evolve unseen; elsewhere, desire for authenticity pulses under layers of expectation. There’s tension between showing up and pulling back, between craving visibility and resigning to its exhaustion, and that tension becomes the album’s emotional backbone. The production by Kaelin Ellis tends toward atmospheric introspection, with soft synth washes, warm drum pulses, and harmonies that cradle rather than crowd. There are moments of R&B warmth, moments when she leans into grooves that could be lounge-room slow burners. Chrysalis continues Europe’s through-line of metamorphosis—and in a moment when many artists attempt vulnerability as image, she lets it be both struggle and liberation, confessional but composed. It feels like a long-awaited reemergence rather than a debut record for those who know what it is to feel both cocooned and ready to fly. — Ameenah Laquita

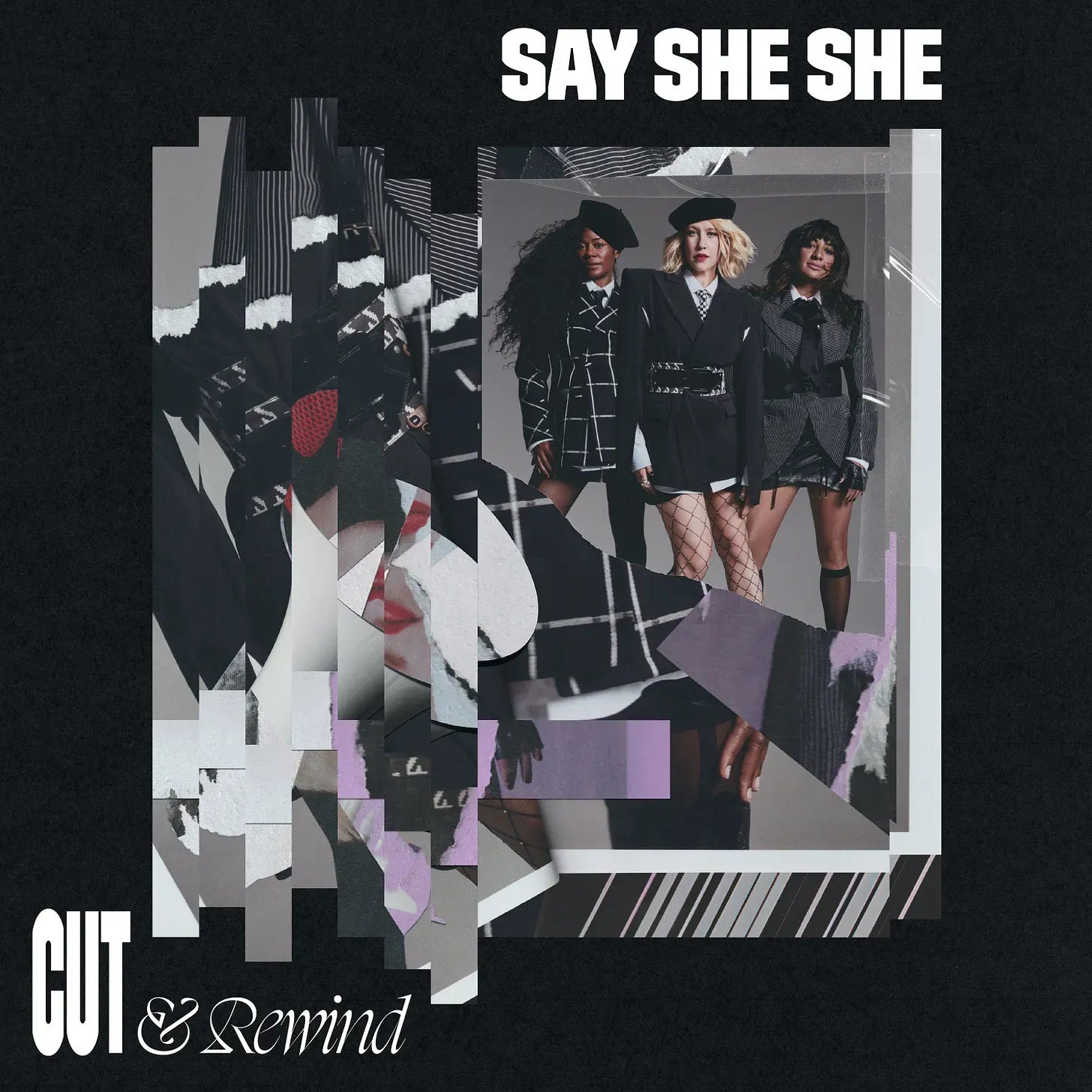

Say She She, Cut & Rewind

Living at the end of the social spiral is difficult, yet there is music that helps one feel that the struggle is paying off, and an obscure sense of joy to withstand the disintegration. Even in that grind, there is survival music. Nya Brown, Sabrina Cunningham, and Piya Malik (as Say She She) drive that pulse Cut and Rewind with the same dependably tight musicianship of Orgone, again. Combined, they are a defiance at work: flowing, careless, and having earlier roots than the fashions. They had previously gained the approval of Nile Rodgers himself before this project, an accolade that was less like a celebrity endorsement and more like an heir to the throne. That flash appears to have brought them into focus. Its relationship-parsing “Chapters” relocate with oily jazz-funk anticipation; the title track initiates jaggedly and victoriously with an almost operatic hook; and the respective “Disco Life” transforms their love of disco into devotion to the genre, reminding of its underground origins and its ability to rescue. Instead of going back to the past, Cut and Rewind picks up on its history and creates something freer, evidence that dance music can be both troubled and joyful at the same time. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Michi, Dirty Talk

Under Stones Throw, Michelle “Michi” Guerrero had spent years searching for the right tone before relocating to a seaside town and letting the songs come to her. Her debut album, created with producers Blake Rhein and Paul Cherry, is equal parts confession and pep talk. She explained that she oscillates between sensitivity and sadness and feeling unstoppable, and that writing these songs helped her reveal the dirt on [her] hands and embrace transformation. “Playing Pretend” captures the difficulty of cutting ties with a partner who has already shown their true colors, packaging that frustration in a self-declared “baddie” anthem. Earlier singles like “There’s No Heaven” envision a sweaty dancefloor where she dreams of ways to win back a lover, while “If You Want Me” calls out a flaky partner with a voicemail-style bridge that recalls Y2K flip phones and underlines how quickly nostalgia can become empowerment. The rawest moment arrives in “Snoobie,” written after she was dumped; she admits she’s “pissed” and reflects on how much power men still have over the women she loves. Michi never pretends to have answers. She documents the messy continuum between heartbreak and healing. — Phil

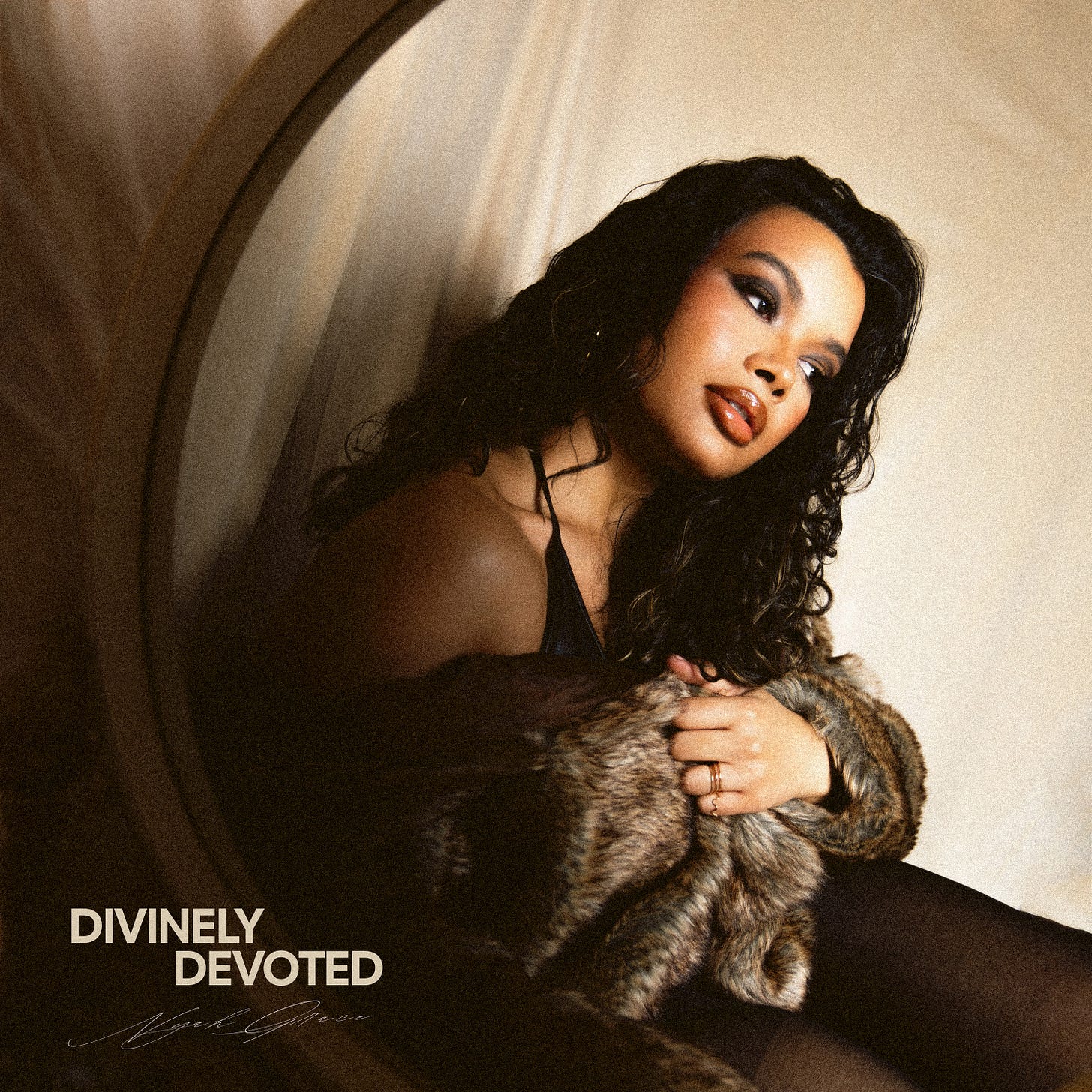

Nyah Grace, Divinely Devoted

When Nyah Grace followed her 2020 debut Honey-Coloured with a run of singles, she seemed like an artist still testing the limits of her neo‑soul palette. On Divinely Devoted, she brings the perspective of a performer who’s spent years on stage and in studios honing her storytelling and tone. She builds scenes from small actions—“We go from fighting to loving in record time/Don’t you see it in my eyes” in “Obvious” sets up the push‑and‑pull she returns to all over the album—and then deepens them with full sentences rather than slogans, like the moment in “Down” when she admits “You just keep bringing me down.” These songs show Grace’s ability to inhabit characters and build small episodes as turning points. Throughout the record, she sings about loyalty, longing, and the pull of physical desire, never hiding behind abstractions. Her voice floats over smooth production, but it’s her unhurried phrasing and candid lyrics that make each song feel like a late‑night conversation with a trusted friend. — Ameenah Laquita

Grimm Lynn, Fire&Smoke

No one does it better than Grimm Lynn. Residing in Atlanta, Georgia—a city whose red clay seems to hold the heat of the sun long after it sets, much like the lingering soul of the Dungeon Family—he previously delivered the solar-drenched warmth of Southern Grooves and the humid intimacy of Sweet Heat. But Fire&Smokeoperates on a different axis, a record that toggles between combustion and suffocation. Coming off of contributing Flwr Chyld’s major-label debut, you get the usual aquatic chords of The Neptunes, and the vocal elasticity of Thundercat here, but on tracks like “Palo Santo,” he orchestrates a cleansing ritual of woodwinds and percussion that feels less like a song and more like a spiritual reset. On “Fire,” he leans into urgent, staccato rhythms that mirror the panic of infatuation. He slows the tempo on “Lilies” to a molasses drag, evoking a wilting romance. — Jill Wannasa

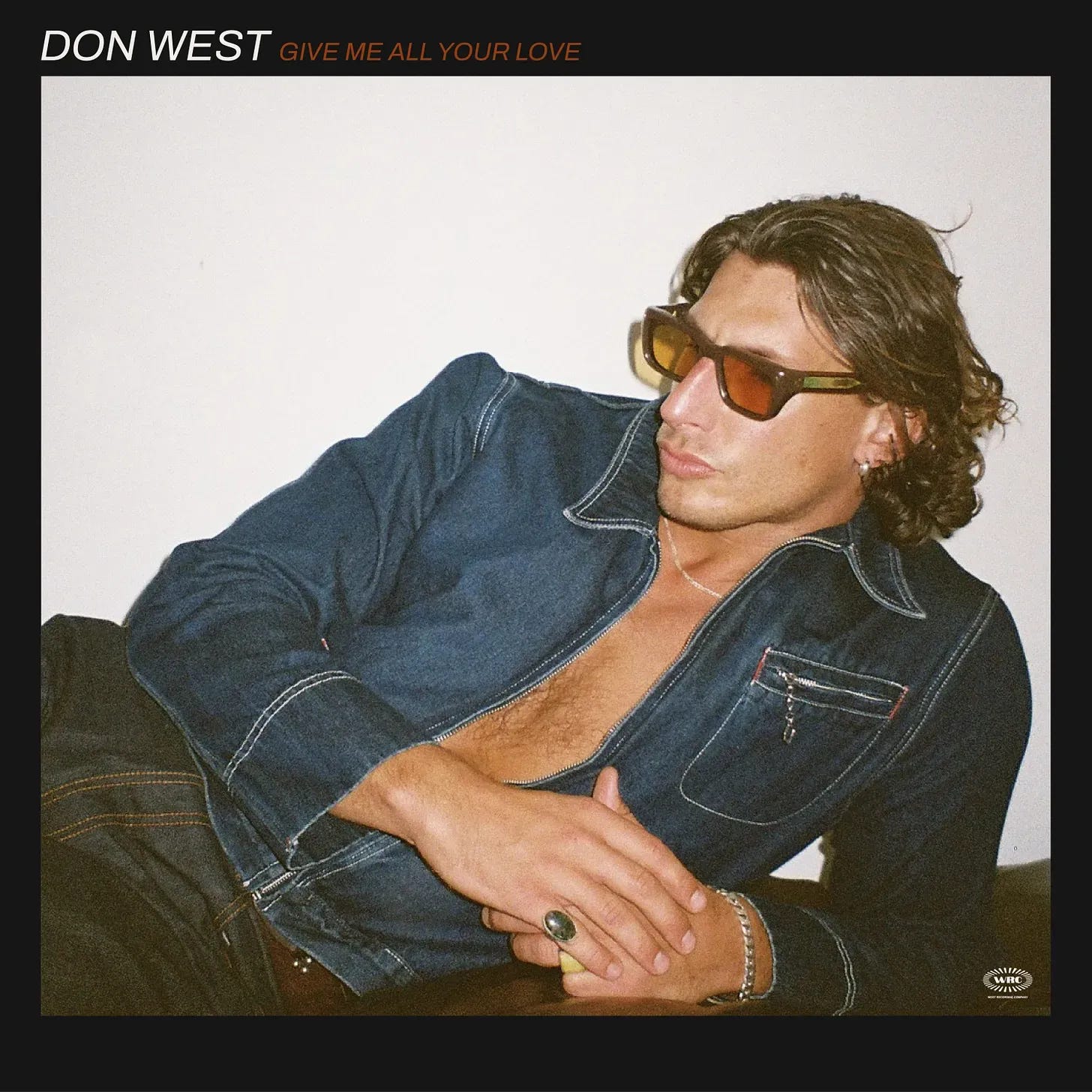

Don West, Give Me All Your Love

Don West found Marvin Gaye’s live albums, where the music barely cuts through women screaming for 40 minutes straight, the kind of frenzy that plants ideas in a young singer’s head. The explosion came fast in his career, as “Small Change” and “Friends” blew up in 2024, pulling him from thousands of monthly listeners to millions. Now there’s Give Me All Your Love, a full-length that locks into the soul renaissance happening globally through artists like Jalen Ngonda and Thee Sacred Souls, but carves out its own humid corner. Nathan Hawes produced and co-wrote the whole thing, recording on the South Coast of New South Wales with multi-track tape and vintage microphones, the twins from Surely Shirley handling choir vocals, a real brass section cutting through analog warmth. You hear Daptone Records in the dripping reverb and funky horns, but West and Hawes push beyond retro worship. On “So High,” jazzy keys dissolve into an extended saxophone solo that could soundtrack a smoky room at 3 AM. “Dreamin” slows to soft-focus drift, nodding to Donnie & Joe Emerson’s 1979 cult classic without replicating it. “Julia” keeps the grooves tight while West questions love with vocals smooth enough to hide the uncertainty underneath. West calls it “coastal soul,” which fits: sun-baked desire meets late-night confession, all captured on tape with the hiss left in. — Imani Raven

The Altons, Heartache in Room 14

Long before they settled into a room full of heartbreak, The Altons developed their chops playing around the Chicano soul scene in Los Angeles. Their secret has always been a conversational chemistry between Adriana Flores and guitarist Bryan Ponce. This vocal blend feels like an old duet group, but it works in both English and Spanish. On the bilingual lament “Perdóname,” they trade lines about regret over a spare funk groove that leans into a bolero cadence. “Del Cielo Te Cuido” shifts to acoustic guitar and bolero, with Flores singing about watching over someone from afar while Ponce answers in harmony. A call-and-response dynamic anchors “Your Light,” where the two singers reassure each other that they’re “guiding me through the dark” over a rolling beat. Elsewhere, “Float” summons the smooth mid-tempo glide of classic soul, and “Tangled Up in You” acknowledges how easy it is to lose yourself in another person’s orbit. Even when the tempo slows, their back-and-forth makes heartbreak sound like conversation rather than confession. — Charlotte Rochel

Georgie Sweet, I Swear to You

British vocalist Georgie Sweet spent years as a featured singer before stepping into the foreground with a debut album that is as much about growing up as it is about relationships. In a Q&A with Ones to Watch, she explained that the record’s themes revolve around hope and the transition from childhood to adult life. Built on layered a cappella harmonies anchored by a subtle drum machine, “The Ones We Loved” addresses departed family members and old friends, making gratitude sound like a prayer in a space. Midway through the album, “All That We Were” examines a relationship that has run its course, and her ability to switch between conversational questions and soaring lines gives the song its edginess. She looks ahead with tentative optimism, echoing the hope she described in interviews. The narrative arc is subtle yet deliberate, showing that growth often happens in quiet increments rather than dramatic leaps. — LeMarcus

James Vickery, JAMES.

Having built up through EPs and collaborations, James Vickery opens this album in a space without compromise—it’s earned through refusal to shrink. Everything from ballads that sting to funk-inflected pop that makes you want to move, and songs that sit somewhere in between, trying on moods, shedding them, finding something honest. Vickery does what he does well, writing about self-reflection, love in its best and worst forms, joy, and the burdens of feeling deeply. He draws from the warm textures of soul and funk, clean guitar lines, keys that slide in softly, rhythm that tugs without overwhelming, and vocal layering that yields richness. On “All In,” he plays with bravado in the verses before admitting in the chorus, “I’m all in, I’m not going anywhere,” a wholesome promise that softens the swagger. The track’s upbeat groove reflects his love of classic R&B and early 2000s pop, and it highlights his versatile falsetto. Even the sultry “Hotel Lobby,” set over a bossa‑nova rhythm, uses its steamy scenario to explore self‑acceptance and vulnerability rather than braggadocio. This isn’t music pretending it isn’t afraid or uncertain—instead, it’s a documentation of all that in real time. JAMES. is a continuation and an evolution, showing how far he’s come in forging a personal voice in UK R&B, arriving just when the genre needs another record that’s comforting and brave. — Imani Raven

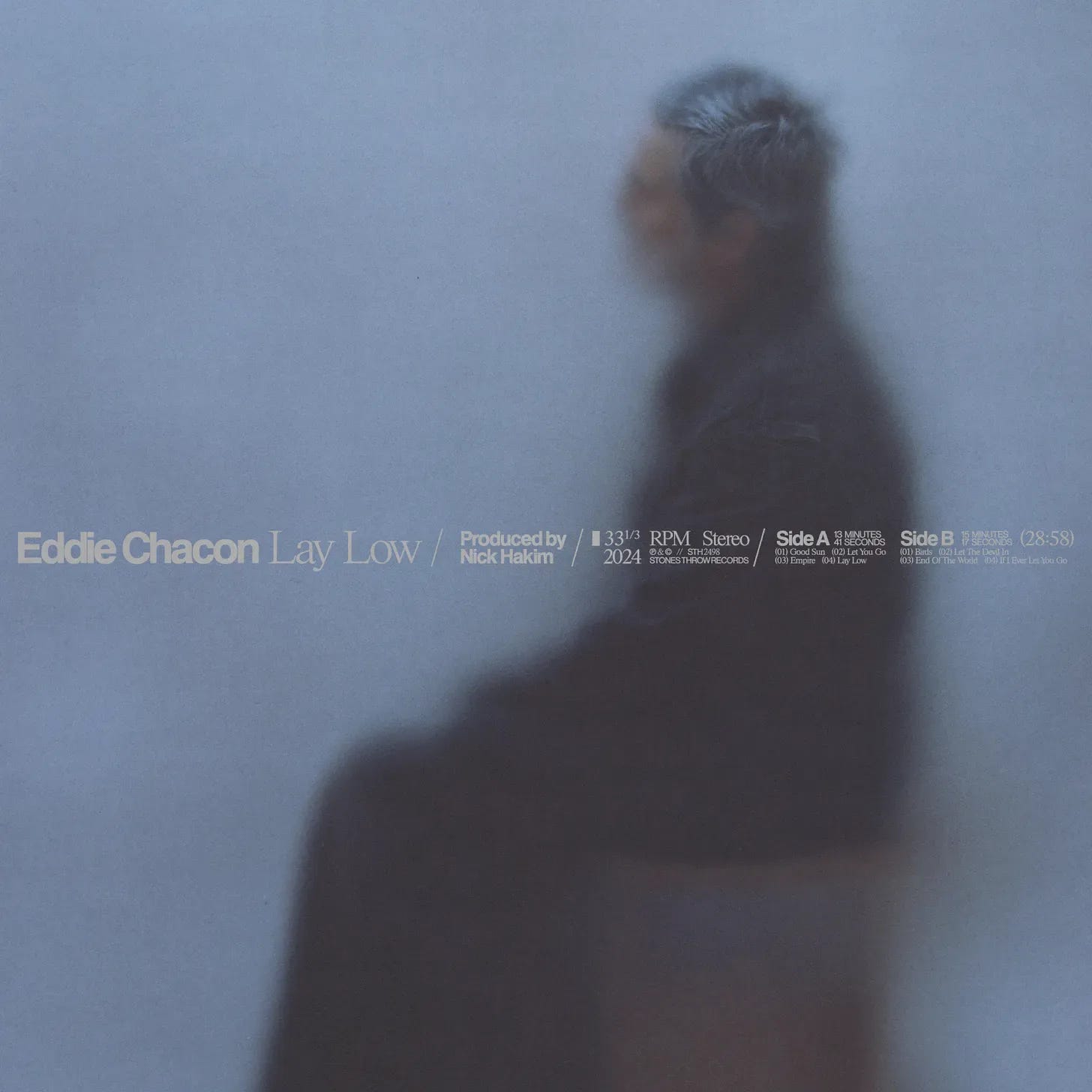

Eddie Chacon, Lay Low

Best known as half of the ‘90s soul duo Charles & Eddie, Eddie Chacon has spent the last few years quietly building a new chapter rooted in introspection rather than chart ambition. His third solo album pairs him with producer Nick Hakim again. It filters grief and hope through woozy, psychedelic soul—bold creativity, sincere introspection, and the disarming presence of an artist who holds nothing back. From the softly unnerving downtempo vibe of the title track itself to the slightly off-kilter instrumentals that frame love, loss, and tentative reinvention, Chacon embraces both the heartbreak and the potential for renewal. “Let You Go” surges with conflicting emotions—the desire to connect, the fear of finality—while John Carroll Kirby’s contribution to “Empire” carries the weight of a danceable but devastating groove. It all culminates in the looming sense that a romance is destined for the wreckage as Chacon channels heartbreak into a cathartic, thirty-minute crucible of sorrow, rage, and a flicker of hope. Lay Low is less a balm than an exorcism—of pain, regret, and what-ifs—demonstrating how music becomes a vessel for surviving the heaviest of blows. — Jamila W.

Léa Sen, Levels

Hailing from London’s DIY scene, Léa Sen uses her debut album to map out a personal universe structured like an old video game. Each song corresponds to a different “level” that reflects a period of her life, and the record feels like wandering through rooms of a memory palace. On the opener “lvl 1 – Home Alone,” she sings over a warm guitar and thick bass line while recounting nights spent lying on a bed chasing clues about a crush. The track’s looped riff and warped vocals make it sound like a private thought turned outward, matching the lyrics’ mix of boredom and hope. “lvl 2 – Aliens” turns that introspection into paranoia, with riffs and swirling soundscapes underscoring her questions about whether unknown figures can be trusted. “WaterSmoke” sounds like a soft confession filtered through walls; she sings “Dehydrate all of our mistakes/Watersmoke down the drain,” using evaporated water as a metaphor for washing away regret. — LeMarcus

James Berkeley, Lost Boy, Golden Hour

As the voice and keyboardist behind the UK neo‑soul outfit Yakul, James Berkeley cut his teeth in jazz clubs and on collaborative EPs. When he announced on Instagram that he would write a full album alone, he followed through by writing, producing, performing, and mixing every note of Lost Boy, Golden Hour. “Just How It Goes” is a letter to a past lover. Berkeley walks a mile in the rain, marvels that someone can be cold even in July, and confesses he’d rather “save a secret than tell a lie.” “Four Leaf Clover” turns nostalgia into a playground scene: he imagines turning back time, notes dirty knees and double rainbows, and remembers trading secrets “like Pokémon cards.” In the love song “Terracotta Love,” he admits to moving too fast and being “guarded,” promising to walk inside his partner’s footprints “till the tide comes up” while repeating “I wanna treat you better, but I’m guarded.” With this record, Berkeley proves he can translate the collective groove of his previous band into solitary confessionals without losing warmth. — Harry Brown

Loaded Honey, Love Made Trees

Lydia Kitto and Josh Lloyd-Watson formed Loaded Honey as an offshoot of the dance-pop band Jungle, but on this debut, they trade club-ready hooks for an unabashed love of early-‘70s soul. The record reads like a scrapbook of a relationship: “Cisco Bay” opens with Kitto cooing, “All my life/We’ll be together/It’s all on track/We’re holding hands,” a doo-wop-style pledge set against gentle percussion. A few songs later in “Over,” she drops her voice to a lower register and counters that optimism with resignation: “Don’t hold my hand/I know it’s tough,” backed by stripped-back bass and brushed drums that evoke a 1950s ballad. The title track laments a love gone cold—“The fire’s cold/You said in words/You did it all before… I’m sorry that I’m leaving out the door”—before slipping into the dreamlike swirl of “Tokyo Rain” and the introspective “Really Love,” where Kitto sings, “Oh tell me/Was it really, really love” over layered harmonies. Even the album’s most upbeat moments have a melancholy edge. “Only Gonna Let You Down” apologizes, while the closer “Hello Stranger” bids farewell with a gentle “Goodbye baby/Don’t you cry.” — Brandon O’Sullivan

Lee Vasi, Love Me to Life

Broadway as a kid (Young Nala in The Lion King), a televised run on American Idol, then a turn toward Rhythm & Praise set the stage for Lee Vasi’s first full album, a Tamla/Capitol CMG release that puts testimony into R&B forms without softening either side. Love Me to Life is built on plain-spoken devotionals and bright, 2000s-leaning arrangements, but the writing carries the weight. “Love Me Anyway” confesses to infidelity and deceit, with Vasi admitting she lied and cheated while her partner loved her unconditionally; she sings “Nada me separa de tu amor” before repeating the plea “love me anyway” as if her life depends on it. On “My Bad Part II,” she revisits a breakdown in friendship, asking, “If I say my bad/Can we still be friends?” and promising to give up old habits. The album’s emotional centrepiece is “He Is,” in which Vasi reflects on years of searching for validation before realizing that divine love has been constant all along. She sings about sleeping well, knowing “I’m His.” These songs show her willingness to name her failures without self‑flagellation and to center stories of reconciliation. By the end of Love Me to Life, Vasi has created a body of work where apologies and declarations are sung with equal conviction. — Tai Lawson

Natalie Slade, Molasses

Sydney vocalist Natalie Slade follows her Eglo debut Control with a new full-length, Molasses. The writing leans into appetite and consequence, and the songs carry that tension without sermon or spectacle; you hear it most clearly on “Unquenchable Craving,” where she spells out the cycle with a clean, memorable couplet—“Sugar, sex, credit cards… what you need is not what you want, dopamine and dopa-don’t”—and then rides the phrase until it turns from confession into resolve. The production stands close to the voice and keeps instruments purposeful, but nothing calls attention away from the lyric; everything gives it traction. “Telephone” works like a late-night check-in rather than a set piece, its chords moving just enough to clear space for her phrasing to rise and hang; the restraint sets up the moments when she leans harder into a line. Across the record, you can hear the pairing with Sampology and contributions from Dan Kye, The DieYoungs, and Laneous as a set of choices that privilege feel and song shape, not sheen. — Imani Raven

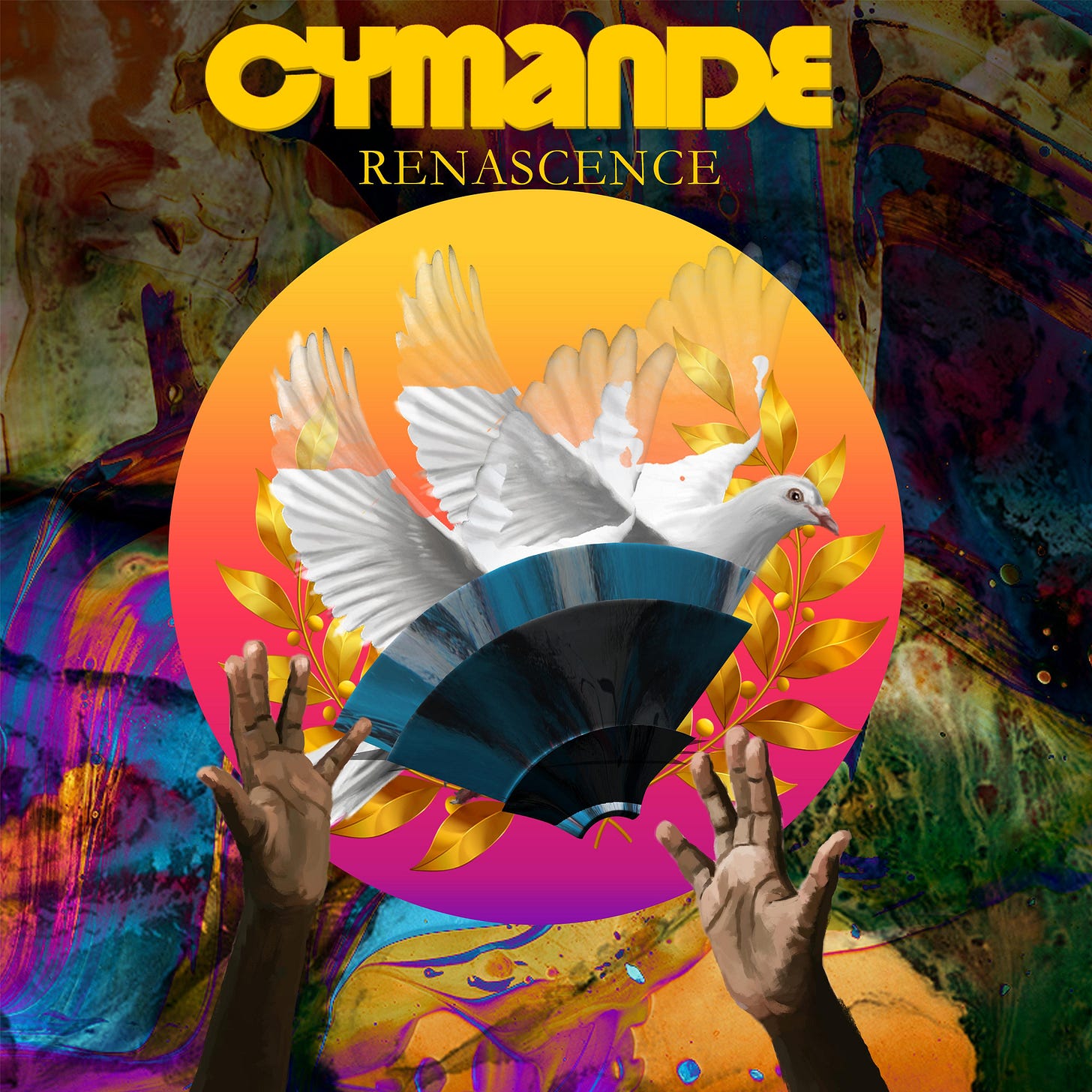

Cymande, Renascence

It has been more than fifty years since Cymande first fused funk, soul, reggae, and Afrobeat into a sound that crate-diggers and hip-hop producers would sample for decades; Renascence brings the London collective back with their original songwriters, Patrick Patterson and Steve Scipio, still guiding the ship. Rather than chasing trends, they reconnect to the social conscience that defined their 1970s work. The group pays tribute to its heroes on “Coltrane,” where a horn-driven jam pauses to declare that “music is the message creation sends,” a motto that sums up their belief in art as a vessel for truth. Guest vocalist Celeste appears on “Only One Way,” a piano-led ballad about choosing a path through uncertainty. “Sweeden” captures the energy of their live shows with call-and-response horns and percussion, while “Darkest Night” addresses racism and morality head-on. The album closes with “Carry the Word,” inviting listeners to share a message of unity and defiance. — Phil

Ben L’Oncle Soul, Sad Generation

On his seventh album, Ben L’Oncle Soul turns inward, exploring fatherhood, romance, and modern anxieties. The French singer became an international name by combining Motown-style soul with a smooth, conversational delivery. “BY YOUR SIDE” backs that sentiment with a lullaby-like promise about his daughter and how becoming a father changed him: “Walking out the door/Everything is calm and safe… I’ll stay close by your side,” followed by a verse where he sings, “I woke up every night just to make sure you’re fine,” pledging vigilance and care. Throughout Sad Generation, he balances vulnerability and control: “DØN’T WANNA FALL” captures the tension between desire and self-preservation, treating falling in love as a risky surrender. “I GØT HOME” channels Motown’s joy as it sings about returning to a place of comfort, and “The Walls” layers reggae rhythms over a tale of emotional isolation. On “HARD TO DØ,” he delivers an infectious hook before guest vocalist Kaylan Arnold steals the spotlight, but the heart of the album remains in his voice and his pen. — Harry Brown

André Mego, Scent of a Woman

Raised in South Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, classically trained on piano, and pushed through pre‑med at Duke before becoming a producer and merch coordinator for 9th Wonder’s Jamla Records, André Mego has long treated hip‑hop as a spiritual syllabus, publishing books like A Wounded Lion and Reverend Duckworth that mine Kendrick Lamar for theology and poetics. Now, as Rapsody’s business partner and co‑founder of the We Each Other creative house, he pours that scholarship into a lush, cinematic ode to womanhood he keeps portraying as “for women to feel seen, not looked at.” If his earlier One Night EP Vol. 1: An Ode to Brotherhoodtightened his production into a compact hip‑hop suite with Chris Patrick and Niko Brim, Scent of a Woman widens the frame, pulling in an ensemble that includes Tanerélle, Domani, Tiffany Gouché, Durand Bernarr, Wyann Vaughn, Reuben Vincent and others across songs like “Setbacks,” “Back & Forth,” “Come to My Room,” “Body,” and “Lover.” The record sits at the crossroads of the soul music he grew up on—Nas and especially D’Angelo’s devotional harmonies—Jamla’s jazz‑rap swing, and the tender alt‑rap balladry of Mac Miller, whose song “ROS” is reimagined as “Sunshine or Rain.” This project is a short film about desire, care, and the radical act of adoring women without ever reducing them to scenery. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Ray Lozano, SILK&SORROW

Cologne-based singer-producer Ray Lozano is intimate, unsparing, and perfectly timed with her pen. Her second album, SILK&SORROW, is built on the idea that softness and pain are two sides of the same coin. This mirrors the contradiction of feeling everything and nothing at once, like “DRAGON” alternates between quiet meditation and bold declarations, with Lozano singing over and over how she loves the way her partner smiles when she’s “being the dragon,” even as she begs for honest communication. On “Better Days,” the project’s lead single, she reflects on a life that seems full yet feels incomplete, noting that some experiences are better when shared. Lozano leans into future-soul production without chasing trends, and she invites collaborators like Pia Allgaier and Salomea for brief guest spots that feel more like indistinct asides than features. — Imani Raven

Jaleesa, Sodalite

Hailing from Copenhagen, Jaleesa set the stage with the single “Woman” and “Your Light,” creating the earlier themes into a debut using straightforward language and subtle details to turn self-worth into an unconscious behavior, articulated, not printed, like a commonplace motto. “Woman” is a statement, with a bare promise and only a few words—“I’m a woman, baby”—and the rest of the songs maintain that same level of tone, though they throw an expanding frame of care, distance, and forgiveness. “Your Eyes” feels like a silent antagonism with everything surrounding her and grounds itself through the talk only to the individual in front of the microphone. “An Ode to My Hair” transforms the mirror moment into a brief celebration of body and heritage, and “Confinement” refers to the frustration of being in a box without melodramatic declarations. Jaleesa creates a history of the hand on the shoulder that is trembling towards serenity, and on Sodalite, it writes like due to whoever is beside her to make it. — Imani Raven

Kyle Dion, Soular

Kyle Dion arrives at Soular with a known toolkit—elastic falsetto from SUGA and a taste for glossy, self-produced R&B sharpened through the SASSY era—and pushes it toward a leaner, dance-warm statement that still centers voice and feel. “SUGA ON THE RIM” rides clipped guitar and springy low end so he can play with tension in his upper register, then “24/7” flips to forward motion, where a chanty refrain about wanting it “every hour every minute every second” turns repetition into momentum. “If I Knew” is the set’s balance point. This regret ballad writes in complete sentences and lands on an ordinary admission—“There’s so many things that I would say if I had one last look at your eyes”—and the production answers by clearing room around his phrasing. Across the record, he leans on crisp drum programming, small rhythm guitar cells, and bright keys, with credits pointing to co-work with Cosmo’s Midnight and The Imports on select cuts, which explains the clean interlock between percussion and synth bass without crowding the vocal. — Charlotte Rochel

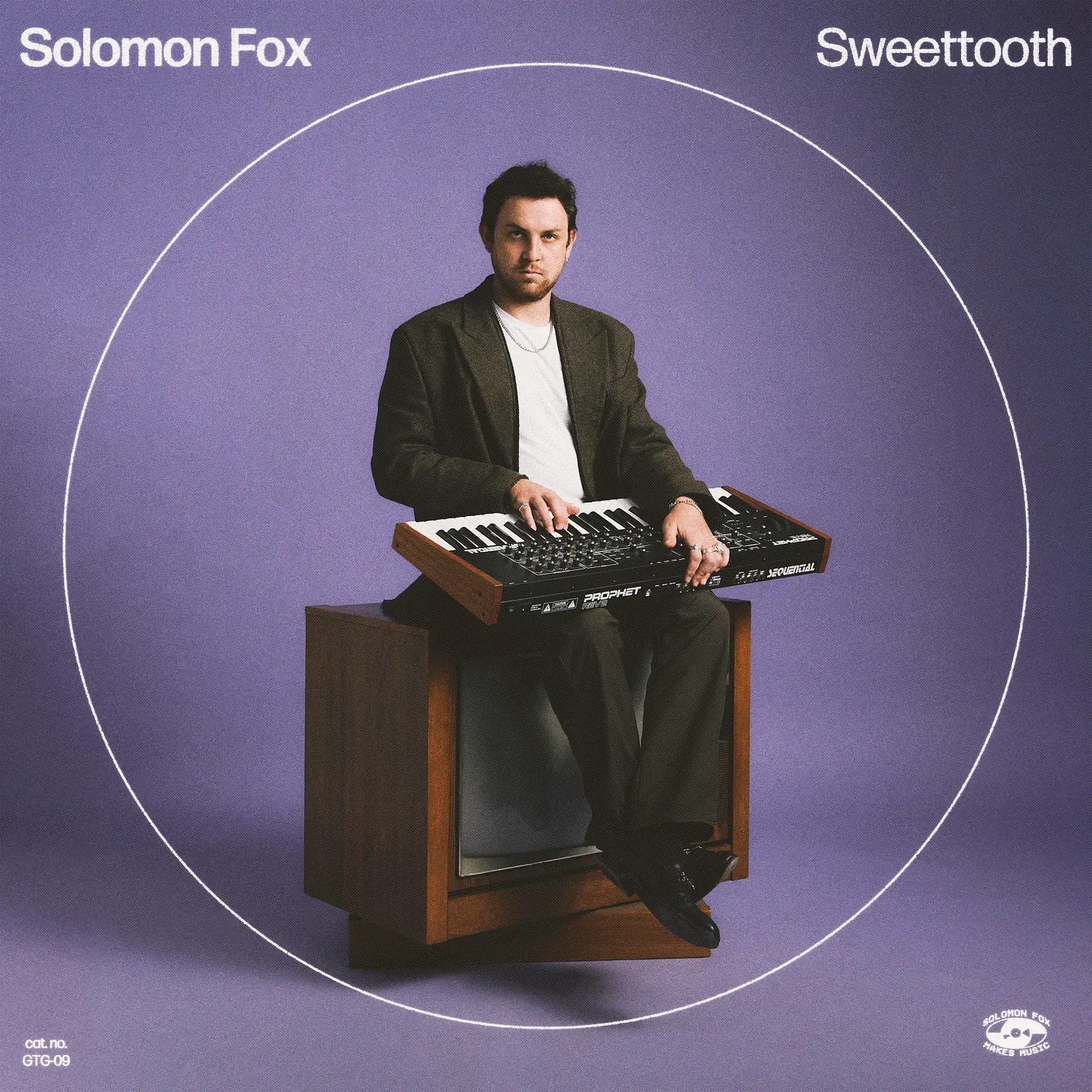

Solomon Fox, Sweettooth

Years after spending his nights in Durham, grinding in small hip-hop and R&B cliques, where he wrote verses with sharpness, often amidst late-night cyphers and demo-tapped recordings that hardly left the studio, Solomon Fox redefined himself alone five years ago, with a handful of not-quite-recorded songs that penetrated ears in what had once been considered the unbreakable closeness of small LA clubs and playlists. At this point, Sweettooth comes as that diary really breaks open, bleeding down the pages with the grief of the connections that had been sever He exposes the silent desperation of seeking reassurance in a relationship that is already disintegrating in places in “Tell Me I’m the Only One” where Fox is willing to sing about the fear of being a mere choice of many becoming the confounded and repetitive apprehension of being caught up in all the others, of making your doubt the bruising constant in a shared dialogue on the phone, the way you pick and carry with you. It is that frailty that carries directly into “Fallin’ Back,” where he exchanges verses with Amaria and asks the name of the magnetic appeal of an ex showing up without announcing to unpack in the absence of the other one. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Jordan Corey, The Tunnel + The Light

Jordan Corey matured from alt-pop experimenter to storyteller intimately tethered to her own life. She wrote The Tunnel + The Light while caring for her mother through cancer, and the record reads like both a diary and an attempt to locate joy when the news is bad. Instead of wallowing, she finds release in songs about self-discipline and independence. On “Friends Like Me,” she checks in with her better judgment, and “Do the Thing” turns self-help platitudes into an invitation to move your body. Her writing handles attraction as more than chemistry—“Dopamine” wonders what desire looks like when you strip away the body’s reactions, and she uses plain language to set boundaries on “Somethin Somethin.” When she confronts inequality on “Try Me,” Corey’s candor pierces: “Boy, you really try me with all of your masculine identity crises” is followed by a promise to “be my best self living free, erase the split between potential and reality,” and she later admits “Sometimes I feed the drama.” — Charlotte Rochel

MRCY, Volume 2

After quietly building a following with their debut, the London‑based duo MRCY return with a tighter collection that seeks to redefine modern masculinity and chart a path toward communal healing. Kojo Degraft-Johnson and Barney Lister laid the groundwork on Volume 1 by pairing a soul singer’s presence with a producer’s arrangement brain. Volume 2 tightens that partnership into songs that move like live charts and read like short stories. Their single “Man” poses the blunt question “What kind of man am I?” and rejects violent posturing, and to “move out the dark and lead with light.” The duo sing about caring for mental health, forgiving oneself, and maintaining faith, often juxtaposing these themes with grooves that recall dance‑hall parties. In doing so, they present vulnerability as a collective act rather than a private confession. Volume 2 insists that joy and introspection belong in the same song and that it’s possible to celebrate while confronting toxic patterns. — Harry Brown

Jonathan Jeremiah, We Come Alive

Jonathan doesn’t retreat into introverted self-analysis beneath the sometimes lush arrangements, but instead marches boldly towards the listeners. He reveals his need to communicate, enchantingly delivering well-chosen, often nature-inspired metaphors. A beautiful woman choir, soulful compositions, and classical elements in the cinematic instrumentation repeatedly push the boundaries of the genre, steering the folk storyteller toward Scott Walker, a crooner, and a chansonnier. The individual pieces all reach a high level, while at the same time providing creative variety under a homogeneous roof. “Counting Down the Days” sounds a bit sweeter and more dramatic, where “Lorraine and the Mermaid” shimmers with a more poetic, sophisticated feel, and the title track has the most exciting mix. “Kolkata Bear” goes faster, is catchier in the ear, quotes the sixties more strikingly; “The Suntrap” scores in dramaturgy, loud-silent dynamics, and psychology; “Lush” delivers first-class Northern Soul. Great, indispensable, warm, nostalgic, and soulful are all these songs—a strong record and another increase compared to the predecessor. — Brandon O’Sullivan

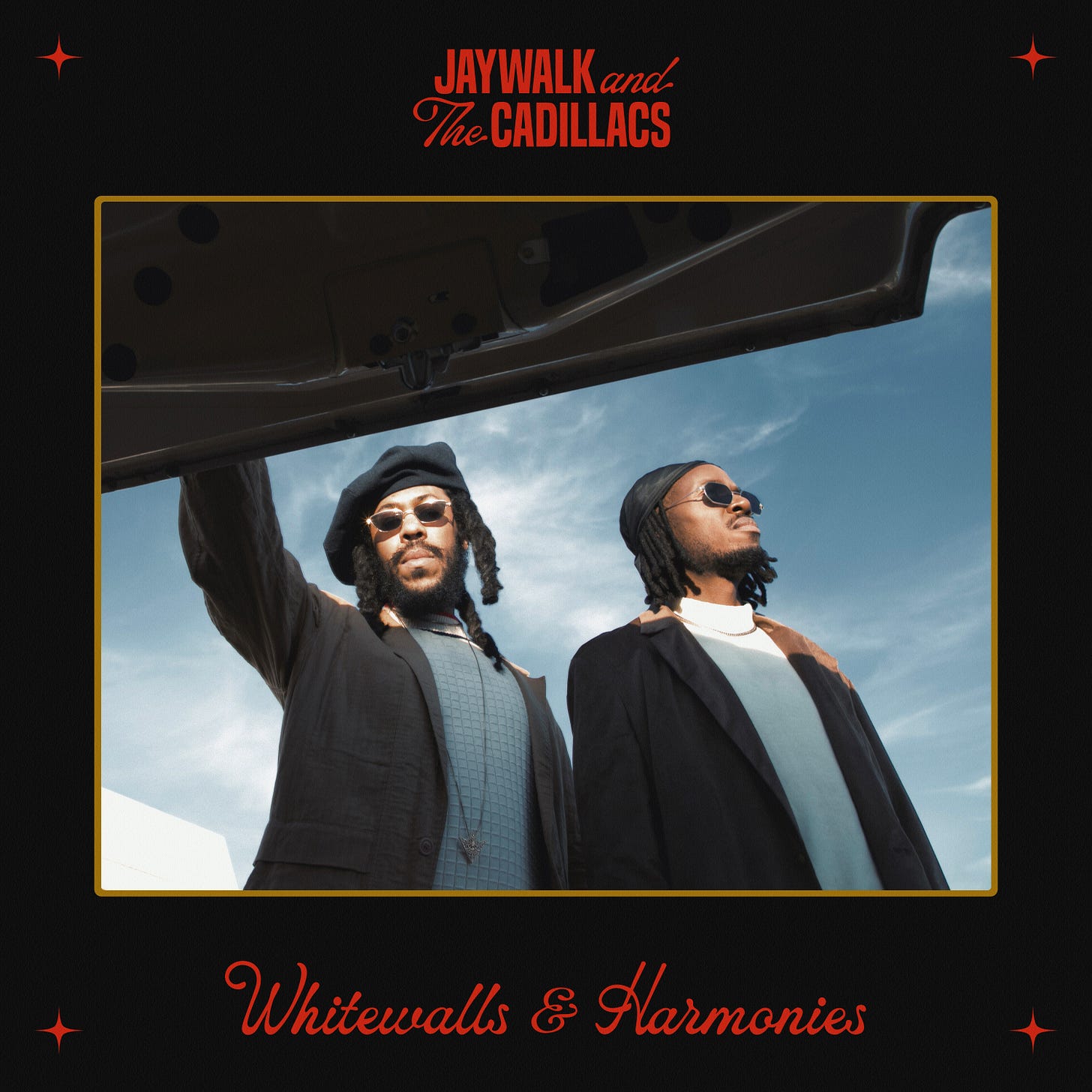

Jaywalk and the Cadillacs, Whitewalls & Harmonies

A transatlantic partnership underpins Jaywalk and The Cadillacs: Detroit singer-producer Illa J, younger brother of J Dilla, joins London multi-instrumentalist Ash Walker, and together they build songs that feel both vintage and unforced. Their debut Whitewalls & Harmonies grew out of sessions in London, Iceland, and on tour, layering hip-hop, neo-soul, jazz, and downtempo electronic music into a sound that is exploratory yet grounded. The chemistry between Illa J and Walker anchors the record; they invite Ke Turner, Harleighblu, Frank Nitt, Belle Chen, and Laville to amplify the mood without losing focus on songwriting. Lead single “In Love” stretches past nostalgic neo-soul to consider how you can feel connected to someone when you’re far apart—its depiction of distance doesn’t dull affection, and Illa J’s vocal range pushes into registers he rarely visits. Turner’s nimble bars on “Danger” with shimmering Rhodes and a hook about feeling priceless even when circumstances threaten to dull one’s shine; the track hints at the album’s title with a metaphor about whitewall tires rolling through troubled streets. The record peaks again when Frank Nitt appears to recount a dream sequence that flips from anxiety to hope and back, only to reprise as a meditative piano piece featuring classical pianist Belle Chen. The musicianship throughout the album feels loose but never sloppy. Whitewalls & Harmonies celebrates the idea that hip‑hop and Neo-soul can be expansive without abandoning their roots, fusing live instrumentation and lyricism into a vivid soundscape. — Harry Brown

Thank you for turning me on to these amazing artist! Masspike Miles’ Album “11 Highland Ave” is an epic piece of work blending hip hop, R&B and jazz exceptionally well.