The 50 Best Albums of 2025 (So Far…)

In the past few months, a very few different records have drifted into rotation, but even though there’s a lot to be desired in certain areas, here are the albums that stood out to us the most so far.

If 2024 felt more dynamic, it is partly because several legacy figures—Taylor Swift with the release of Tortured Poets Department, Beyoncé with her genre-bending pivot on Cowboy Carter, Kendrick Lamar with a world-tour document that’s now underway since the surprise-release of GNX, and SZA with an expanded edition of SOS—dropped statements that combined cultural heft and marketing spectacle. 2025 has yet to offer a comparable lightning rod, and the absence is conspicuous. The upside is that independent voices (with a tiny percentage of releases under a major) face less scrutiny when they experiment, and listeners willing to dig find a landscape teeming with small-label rap minimalism, jazz experiments, soul gems, and global hybrids that draw cadence ideas from various genres. These micro-scenes rarely register on first-week sales spreadsheets, but history tends to remember the records that grow outward from cult status rather than those designed to dominate the quarter.

So the year’s relative quiet says less about a creative drought than about an attention economy in which big-tent consensus is more complex to manufacture. Albums destined to “stand the test of time” may already be here; they simply arrive in stealth, demanding slower listening habits. Whether the back half of 2025 delivers a marquee surprise or not, the future canon will likely draw from today’s overlooked releases, not from the still-simmering anticipations that dominate headline chatter. That said, let’s get into the albums that stood out to us more.

SAULT, 10

SAULT are so unpredictable. Their latest stealth drop opens with clipped, initial-only titles that read like coded mantras, reinforcing the collective’s insistence on message over celebrity. “T.H.” sets the tone with a polyrhythmic drum kit swirling around an electric-piano vamp before a children’s choir enters, turning the groove into affirmation rather than mere jam. Throughout the album, producer-architect Inflo layers live bass, hand percussion, and orchestral swells; on the mid-tempo “P,” a rubbery bassline locks with rim-shot snares while stacked vocals trade phrases that blur the line between call-and-response and internal dialogue. SAULT’s habit of releasing then briefly deleting music intensified the album’s mystique when it appeared on Good Friday, vanished, and returned on Easter Sunday—a resurrection gesture that matches the record’s themes of endurance and spiritual rebirth. Yet 10 isn’t pious; “S.I.T.L.” runs an Afro-disco pulse under dubby guitar stabs, and “W.A.L.” floats a lilting West African high-life line over rousing congas, as if stitching together a diasporic sound quilt. SAULT’s anonymity ultimately spotlights that pan-Black conversation in the music itself—a conversation that feels urgent, communal, and insistently hopeful. — Phil

José James, 1978: Revenge of the Dragon

José James cut the entire set to two-inch tape inside Dreamland, a converted church whose wooden rafters trap cymbal spray and ambient hiss, so the record breathes like a crowded club rather than a DAW grid. BIGYUKI’s analog synths fizz against Jharis Yokley’s cracked-rim snare while a three-horn frontline of Takuya Kuroda, Ebban Dorsey, and Ben Wendel punches lines that feel lifted from a Shaw Brothers soundtrack. “Tokyo Daydream” drapes that brass over a rubber-band bass ostinato, then slips into double-time handclaps that evoke neon alleys at midnight. The Michael Jackson cover “Rock With You” slows to half-speed, James stacking his voice into woozy harmonies while a dubbed-out clavinet wobbles beneath muted trumpet. “They Sleep, We Grind (for Badu)” filters a clav groove through tape echo, echoing its mantra-like hook across speaker cones until it feels more ritualistic than a song. Original “Rise of the Tiger” rips forward with fuzz bass and kung-fu dialog samples, paying tribute to James’s own martial-arts practice. “Last Call at the Mudd Club” ends on a bent tenor-sax scream that fades into the studio’s natural reverb, leaving only creaking floorboards and tape hiss as the lights cut. — Brandon O’Sullivan

doseone & Steel Tipped Dove, All Portrait, No Chorus

The title is literal. Across a sprint of fourteen miniatures, doseone refuses to settle into hooks, instead firing off knotty couplets that twist, rewind, and splinter before any comfort can set in. Steel Tipped Dove meets that restless energy with production that ricochets between dust-covered breakbeats, abrupt tape stops, and pockets of negative space; the beat change inside “Went Off” feels like a floor collapsing beneath your feet, only for a warped vocal sample to catch the fall. Throughout, doseone keeps one foot in the abstract and one in the tangible: “Scales Sway” spirals through surreal imagery—he compares his flow to a “python” uncoiling—yet lands on an eerily plainspoken refrain, the voice suddenly naked in the mix. Cameo verses (Open Mike Eagle, billy woods, Myka 9) don’t break the spell; they feel drafted into doseone’s private language, volleying syllable games rather than chasing spotlight moments. The result is a record that feels like a sketch-book filled at manic speed—pages torn out, ink still wet, imagination outrunning the metronome.— Phil

Sunny War, Armageddon In a Summer Dress

Sunny War writes blues that feel carved out of porch floorboards, yet this album pushes beyond lone-guitar intimacy. She circles memory and haunting. The gas-leak hallucinations she endured while writing in her late father’s century-old house bleed into “Ghosts,” where she sings, “The walls breathe out the stories I buried,” her vibrato fluttering like a draft under a door. Guest punk icon Steve Ignorant shouts a mid-song refrain on “Walking Contradiction,” underscoring War’s lifelong tether between folk tradition and anarchist politics. Yet it is the quieter “Rise” that delivers the emotional knockout, a gospel shuffle where she insists, “Every scar is a seed,” supported only by muted slide guitar and brushed snare. The album’s title permeates its tension as apocalypse arrives, draped in bright fabric. Instead of lamenting, War treats chaos as a creative catalyst, her playing darting from jazzy seventh chords to furious punk strums within the same chorus, proof that resilience can sound both ragged and luminous. — Tai Lawson

Reuben James, Big People Music

The British pianist’s songwriting matures into expansive, chorus-rich neo-soul that nods to Donny Hathaway and late-period D’Angelo. Opener “Elders” breaks in on a stacked gospel-choir vamp, James’s falsetto gliding above clipped wah-guitar. Horn arrangements bloom across the record, arranged as counter-melodies rather than mere stabs; “Sunset in Soho” features a flugelhorn line that mirrors the vocal melisma on its final refrain, giving the song a circular symmetry. The piano remains the anchor, block chords in the low register, right-hand trills recalling Oscar Peterson, but the rhythmic emphasis sits firmly in the pocket, courtesy of swung rim-shots and hand-clap overdubs that keep each hook buoyant. — Jamila W.

Pink Siifu, Black’!Antique

Siifu’s latest canvas is massive, featuring nineteen tracks that blend glitch, gospel, trunk-rattle bass, noisy punk interludes, and chopped-and-screwed radio static, sequenced like a pirate-signal variety show. He jumps voice-boxes at will: high-pitched croons melt into barked ad-libs, then retreat into woozy whispers that sound recorded across the room. That shape-shifting is thematic: opener “BLACK’!ANTIQUE’!” welds Memphis-style 808 thumps to a swirl of flutes while Siifu narrates diasporic time-travel (“I been here/I been gone/I been back”) as if memory itself is buffering. Mid-album peak “1:1[FKDUP.BEZEL]” drapes Bbymutha’s drawl over a queasy Rhodes loop, turning a flex verse into a séance for Southern rap lineages. Even the shortest sketches carry narrative heft: the 92-second “OUTSIDE’!” crams police-scanner chatter, distorted jazz chords, and Siifu muttering “tryna breathe” until the tape snaps. Across the sprawl he renders oppression, joy, grief, and celebration as overlapping radio frequencies—sometimes they harmonize, more often they fight for bandwidth. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Durand Bernarr, Bloom

Bernarr has long balanced irreverent humor with devotional singing, and Bloom finds that equilibrium fully mature. The record’s opening salvo “Generous” glides on a plush synth-bass pocket while his falsetto flips between coy invitation and gospel-esque ad-libs, illustrating how secular desire and sanctuary can occupy the same breath. Elsewhere, “Flounce” recruits New Orleans bounce cadences to tell off energy vampires with a grin, a reminder that self-protection can sound like a block-party chant rather than a stern lecture. Even the quiet-storm ballad “Unspoken” refuses to chase respectability, breaking into conversational asides as though Bernarr can’t help but let them see the thoughts forming in real time. Across the album, stacked harmonies nod to the singer’s background touring with Erykah Badu, yet the production prefers glossy keyboard chords and sub-bass pulses to retro re-creations, planting his vintage phrasing firmly in the digital now. The result feels like a house-party sermon delivered by your funniest friend—profane, kind, and impossible to tune out. — Jamila W.

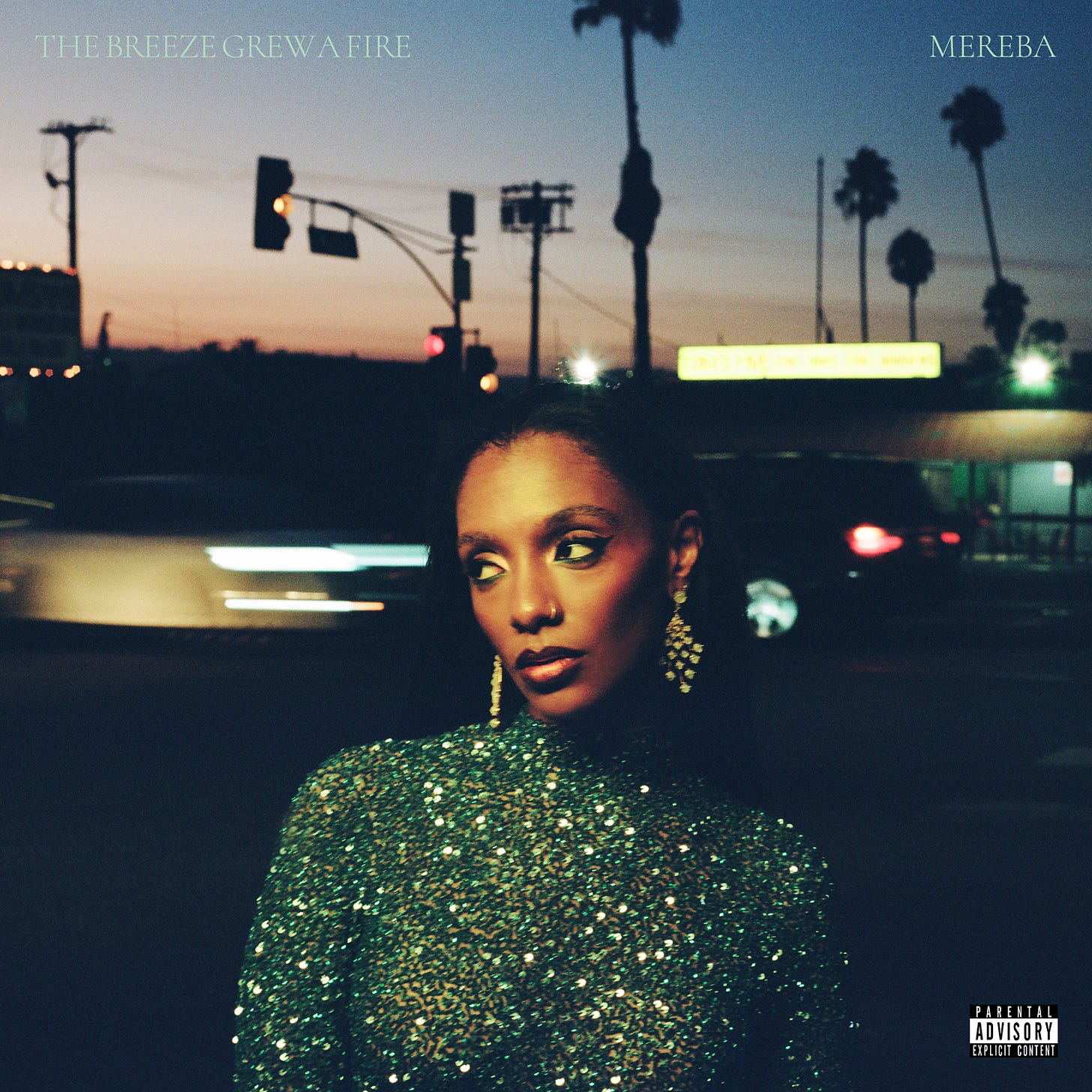

Mereba, The Breeze Grew a Fire

Mereba knits guitar-led folk motifs into a warm soul palette that rarely rises above a simmer yet never loses momentum. Throughout the record, she reflects on kinship and self-trust, themes she has said honor “unconditional love and support.” The lead cut “Counterfeit” urges individuality with the line “Don’t let them counterfeit you,” anchoring the project’s insistence on authentic self-definition. Underneath that refrain, a faint slap of bass and hand percussion draws the ear without eclipsing her calm vocal stacking. “Ever Needed” folds the metallic twang of the Ethiopian krar into a mid-tempo shuffle, foregrounding heritage without treating it as ornament. The krar’s reappearance elsewhere supplies a subtle through-line in place of overt hooks. Even the quiet moments carry pulse; a lightly distorted guitar in “Starlight (My Baby)” hints at funk while keeping dynamics restrained. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Annie & The Caldwells, Can’t Lose My (Soul)

The West Point, Mississippi family group spent decades singing in roadside sanctuaries before Luaka Bop wired up a mobile studio inside New Home #2 Missionary Baptist Church to capture their “disco-soul gospel” in two weekend sessions. Annie Caldwell’s daughters arrange three-part harmonies that glide over guitar lines soaked in phase-shift—an echo of their teenage love for Chic records smuggled into rehearsal under the pews. The ten-minute centrepiece “Can’t Lose My Soul” modulates from 6/8 testimony into four-on-the-floor praise without losing the raw hand-clap ambience that producer Matt Colton left unedited to preserve sanctuary bleed. The album chronicles marital doubt, working-class exhaustion, and spiritual stubbornness, yet every chorus doubles as a promise: “wring my heart, but the melody stays clean,” Annie growls, turning hardship into groove. — Imani Raven

Miles Cooke, Ceci N’est Pas un Portrait

Cooke titles his record after Magritte’s famous non-pipe, an apt wink for music obsessed with perception and misdirection. The emcee spits in long, breathless torrents that recall Def Jux-era word density, yet the beats are spare: upright-bass loops, muffled kick drums, brief piano stabs, all leaving oxygen for his syllable mazes. On “negus,” he starts in anxious near-whisper—“I could’ve sworn I heard fate whisper, then along came the pressure”—and gradually escalates to a gritted-teeth roar, mirroring a panic attack cresting and crashing. “The Book of Job Part II” frames survivor’s guilt in biblical language, Cooke flipping scripture into sucker-punch gallows humor—“brief leisure edit life to cue the applause break”—over a woozy Rhodes vamp. His chess-metaphor duet with Defcee, “Zugzwang,” snakes through internal-rhyme coils so tight they feel almost claustrophobic until the hook erupts in shouted gang vocals, a rare communal exhale. — Harry Brown

Oklou, Choke Enough

Oklou stretches vaporous synth-pop into near-weightless shapes that often feel closer to chamber music than club fare. Sparse drum programming leaves pockets of negative space where her soft vocal lines drift without gravity. She called the record a way to “discharge emotions,” and that catharsis permeates even its quietest passages. “Ict” layers looped voice fragments until they blur into a choir of sleep-talkers. Trumpet bursts recorded in a Paris apartment punctuate “Harvest Sky,” their brightness contrasting with the half-time pulse. Those horns are run through granular delays so each swell smears like wet paint across the stereo field. “Family and Friends” poses uneasy questions about future motherhood while riding sub-bass that never quite resolves. The record rewards patience, asking listeners to lean in rather than reach for the skip button. — Charlotte Rochel

clipping., Dead Channel Sky

The trio opens with fifty-one seconds of electronic hiss and detuned radio chatter, a prelude that feels like someone hand-scanning an abandoned satellite band for signs of life. “Dominator” answers the call; Daveed Diggs raps in clipped bursts synced to distorted drum-and-bass hits, sketching an unnamed protagonist who hacks power grids “with synaptic wire and borrowed rage,” a line delivered so quickly it feels typed rather than spoken. The song bleeds into “Change the Channel,” where a saw-toothed synth riff cuts in and out like an emergency broadcast, invoking the thrill and terror of living inside a perpetual signal. Diggs rarely claims an “I,” instead voicing avatars caught in capitalism’s circuitry. A nightclub gatekeeper who sneers, “God is not here, he forgot to rock his mirrorshades,” a shell-shocked code-slinger coaxed into a mercenary gig with the promise of eternal cloud storage. The collisions between these stories create a widening paranoia, each of them hints that private histories are forever one data breach away from public ruin. — Harry Brown

Bad Bunny, Debí Tirar Más Fotos

Bad Bunny opens his arms to the sweep of Puerto Rican sound history while pointing the memories toward tomorrow’s dance floor. Plena hand-drum cadences slide into reggaetón dembow, jíbaro string runs dart across house kicks, and salsa horns flare like brass sunlight. Rather than treat those idioms as retro ornaments, he stitches them into the rhythmic fabric so tightly that the shifts feel like breathing. The four-on-the-floor shimmer of “El Clúb” suddenly tilts into a hand-percussion breakdown that turns a nightclub into an outdoor comparsa. A student salsa orchestra fuels “Baile Inolvidable,” their call-and-response energy mirroring his nostalgia without slipping into kitsch. Even the romantic “Turista” refuses postcard fantasy, comparing a fleeting affair to visitors who consume an island they will never rebuild. He seeds voice-note asides and documentary shards that tether dance beats to lived experience. Long-time ally Tainy shares programming with newer hands, yet the beat palette stays purposely rough, as if recorded outdoors. — Charlotte Rochel

PremRock, Did You Enjoy Your Time Here...?

The title’s polite question hangs over every bar, turning each anecdote into a border crossing between nostalgia and existential dread. “Angel’s Share” sets the tone with a horn-flecked loop that staggers like jet-lagged footsteps; PremRock locks into its lurch, musing on airports and AA pamphlets before dryly admitting, “I collect layovers like postcards nobody asked for.” His delivery lands somewhere between deadpan stand-up and late-night confessional, letting punch lines and revelations share the same breath. Controller 7, Blockhead, and Sebb Bash supply beats that feel gently unsettled, lo-fi textures, chords that detune by micro-cents, kicks that arrive a hair ahead of the snare, mirroring the record’s thematic liminality without drowning it in production fireworks. When billy woods turns up on “Receipts,” the mood darkens; his verse rummages through “unpaid invoices of the soul” while a muted trumpet coughs in the background. — Phil

FKA twigs, Eusexua

Twigs returns with a forty-three-minute suite that glitters like chrome at sunrise yet keeps the bruised intimacy of her early work. She sets the tone by defining a self-coined word for the instant before inspiration, while breakbeats snap around her chant-like hook. Club-pop and avant-techno form the backbone, but every rhythm stretches or contracts around whistle-register flourishes. “Drums of Death” fires warp-speed percussion yet blooms into string pads that nod to trip-hop without imitation. Cameos stay subtle—Koreless threads glacier-cold synth stabs through the mid-section while her voice glides overhead. Texture trumps spectacle; synths fizz like dry ice while percussion clicks like rivets. “Striptease” closes with harpsichord-tinged chords that drift into silence as if the dancer has stepped off an empty stage. — Charlotte Rochel

Southern Avenue, Family

Memphis-bred but globally inclined, the band tracked these songs live after a month-long residency at Stax Museum’s soundstage; that room’s slapback bounce colours every snare hit. Opener “Long Is the Road” drapes churchy organ over Israeli guitarist Ori Naftaly’s blues bends, while Tierinii Jackson sings about ancestors “humming freight-train keys.” “Found a Friend in You” slides from gospel shuffle into Afro-beat breakdown—a nod to bassist Evan Sarver’s Nairobi childhood—without losing hand-clap grit. The title cut turns a simple three-chord vamp into a call-for-unity anthem; the repeated refrain “blood is a tune, not a chain” underscores the album’s fixation on chosen kinship. — Jill Wannasa

Mourning [A] BLKstar, Flowers for the Living

The Cleveland collective’s newest is equal parts funeral dirge and liberation hymn. Opener “Stop Lion 2” fuses distorted bass drone with a field-recorded Baptist shout, interrupted by a spoken-word salvo from Lee Bains that sounds like Gil Scott-Heron channeled through post-punk megaphone. Elsewhere, “Letter to a Nervous System” layers tape echo on dour trumpet lines, evoking the echo-chamber anxiety of the album’s title. Yet hope persists: closer “88 pt.” hinges on a modal, Major-7th guitar vamp that brightens each chorus, suggesting blossoms pushing through concrete. Multiple lead vocalists trade lines like communal testimony, transforming grief into collective propulsion. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Yukimi, For You

Yukimi Nagano steps outside Little Dragon, trading neon synth-funk for a spacious jazz-tinted palette. A brief spoken prelude names shared humanity as the album’s guiding principle. “Make Me Whole” glides on brushed drums and Rhodes chords, her feather-light vibrato hovering just above the groove. Vocals remain front and center, recorded dry so that every breath feels inviting. String arrangements by Håkan Wirenstrand shade “Elinam,” lyrics aimed at her son. Pos of De La Soul drops a verse that folds boom-bap cadences into the otherwise airy composition. “Sad Makeup” pairs brushed snares with tremolo guitar, casting a twilight mood reminiscent of neo-soul’s quieter corners. Yukimi builds power through quiet conviction, offering a document of vulnerability that invites us into her orbit. — Tai Lawson

Brandon Woody, For the Love of It All

Woody’s trumpet tone sits somewhere between Clifford Brown’s caramel warmth and Christian Scott’s breathy edge, but his compositional sense is firmly of the present: trap-lilted hi-hats coexist with modal piano clusters and snatches of spoken-word prayer. The album is structured like a church service turned block party—opening fanfare, communal affirmation, ecstatic peak, contemplative benediction. Upendo, his long-running quartet, locks into polyrhythms that reflect Baltimore’s go-go legacy even as synth textures nod toward cosmic-jazz futurism. On “Never Gonna Run Away,” Woody quotes “Lift Every Voice and Sing” before vaulting into a double-time solo that feels like an asphalt sprint through North Avenue at dusk. He refuses the jazz-world trope of geographic migration, choosing instead to root the music in the city that raised him; the result is a record that radiates place-based love without turning parochial, achieving universality through hyper-local detail. — Phil

Blu & August Fanon, Forty

Producer August Fanon gifts Blu a kaleidoscope of soul fragments, detuned Rhodes chords, dusty swing drums, woozy flute runs, and Blu answers with verses that treat aging like an open-mic testimony: honest, cracked, unafraid to laugh at itself. The sequencing is clever: “Forty” sets the tone with jubilant horn stabs, then a relay of underground luminaries (Mickey Factz, Charles Hamilton, R.A.P. Ferreira) file in, each handed a beat that skitters between boom-bap minimalism and kaleidoscopic jazz loops. Every hook reconfigures the LP’s central mantra—worth is measured in wisdom, not timeline metrics. Mid-album, “Love (1-4)” runs nearly eight minutes, fluttering through four pocket-grooves while female vocalists stack harmonies like 1970s Roy Ayers sessions; by contrast, “Bible” cuts to a two-minute sermon over funereal organ. The quick pivots mirror turning pages of a photo album: snapshots of fatherhood, youthful missteps, spiritual doubt. Blu never hides the scuffs in his flow, but Fanon’s crate-digger textures wrap each confession in warmth, making the record feel less like nostalgia and more like a living scrapbook still being written. — Harry Brown

Saba & No ID, From the Private Collection of Saba and No ID

Saba’s partnership with Chicago elder No ID yields a record that feels handwritten in the margins of family photo albums—snapshots curled at the edges, annotated in fountain-pen blue, passed down with stories half-true because they need to be. “Every Painting Has a Price” sets the thematic stakes. Saba warns, “What if it drove us out our minds? I guess every painting has a price,” equating creative obsession with auction-block extraction. No ID’s sample of Mountain’s “Long Red” —filtered drums, grainy crowd noise—acts less as a nostalgic wink than as a reminder that Black cultural labor is forever collaged from fragments of older stories. Elsewhere, Saba toggles between playful intimacy and durable grief, where one verse jokes about dating apps, the next wrestles with the unpayable cost of inherited trauma, yet the pivot feels natural because community lore holds both jokes and elegies in the same breath — Phil

billy woods, Golliwog

When Golliwog opens with “Jumpscare” with warped horns and tape hiss, it sets a claustrophobic mood that never fully lifts. billy woods raps in dense, imagistic bursts, stacking references to colonial history, horror cinema, and everyday micro‑aggressions until the lines feel like overlapping newspaper clippings. Throughout the album, the production pivots between dusty jazz loops and abstract sound design. “Star87” floats over a detuned vibraphone riff that keeps slipping out of key, while “Misery” uses a brittle guitar figure that fractures under heavy reverb. Guest spots amplify the kaleidoscope; Bruiser Wolf’s off‑kilter drawl on “BLK Xmas” adds sardonic humor, Despot’s surgical precision on “Corinthians” sharpens the track’s edges, and ELUCID appears multiple times, his voice acting as both mirror and foil to woods’ weary baritone. The middle stretch (“Waterproof Mascara,” “Counterclockwise,” “Pitchforks & Halos”) digs into paranoia, with drums that drop out unexpectedly, forcing the listener to cling to woods’ internal rhythms for footing. Near the end, “Lead Paint Test” and “Dislocated” widen the sonic palette with industrial clangs and ghost‑choir samples, pushing the project into near‑apocalyptic territory. Despite the heavy subject matter, there is a sly playfulness in woods’ rhyme schemes; multisyllabic patterns tumble into sudden blunt phrases, mirroring the album’s thematic tension between performance and painful memory. — Phil

Ghais Guevara, Goyard Ibn Said

Structured in two acts, Guevara’s concept piece follows a fictional anti-hero who rises from corner rap star to luxury-brand demigod before watching the spoils curdle. Act I’s centerpiece “The Old Guard Is Dead” pairs roiling trap drum-programming with a compressed soul sample that sounds like vinyl spun backwards; Guevara rips through double-time boasts only to undercut them with “Aim for the moon, rose from the gallows”—a couplet that frames triumph as execution by another name. Act II flips the palette: “Leprosy” slows the tempo, substituting hazy guitar chops while he sneers, “actions don’t match their lyrics,” a self-indictment as much as industry critique. Throughout, his flows dart between Philly street punchlines and West African griot cadence, a nod to the historical Ibn Said, whose name he borrows. By finale “I Gazed Upon the Trap with Ambition,” the beats have thinned to skeletal clicks, and Guevara’s voice fractures into half-sung laments, the anti-hero finally staring into luxury’s hollow center. The narrative gambit never feels forced because Guevara’s technical fireworks—polysyllabic rhyme chains, sudden meter shifts—keep the story wired to the adrenal rush of outstanding rap records. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Wretch 32, Home?

Wretch’s writing has always balanced nimble wordplay with confessional heft, but here the stakes feel existential. The opening track juxtaposes news-clip sirens with a choir that could have drifted in from Brixton’s Pentecostal churches, underscoring his question: Can a nation that polices your very breath ever be “home”? Over minimalist, hi-hat-heavy production, he threads Jamaican patois into North London argot, treating language itself as a contested post-colonial terrain. Mid-album standout “Diaspora Dinner” samples clinking cutlery and dub bass, turning the simple act of sharing food into a metaphor for generational memory. The project ends not with resolution but with a question-mark bass-drum thud, Wretch whispering, “Maybe I’ll find it in my son’s accent,” a line that lingers long after the music fades. — Ameenah Laquita

Ambrose Akinmusire, Honey from a Winter Stone

Ambrose Akinmusire stages conversations among a trumpet, a string quartet, a synthesizer, and Kokayi’s improvisational vocal lines, each testing the acoustics of grief and survival. “Muffled Screams” creep from near silence, ride-cymbal taps flicker beneath strangled trumpet whispers. A spoken recollection of a near-death experience folds into Kokayi’s free-meter rap, turning autobiography into communal mourning. Midway, he box-cuts the stillness with spoken-word fragments—“We bloom under asphalt, we oscillate”—setting off a volley of call-and-response between voice, viola harmonics, and skittering ride cymbal. Homage to Julius Eastman surfaces in long drones and additive structures that slowly pile tension. On “s-/Kinfolks,” a half-hour epic, the band ebbs into near silence before a sudden gravitational tug of synth bass drags the ensemble into a free-wheeling sprint, Justin Brown’s rim-shots ricocheting like loose stones in a dryer. The effect is cinematic yet intimate, mapping the interior landscape of grief, resilience, and community without resorting to narrative lyrics. Few jazz records this year feel so simultaneously vast and hand-held. — Nehemiah

Yugen Blakrok, The Illusion of Being

Yugen Blakrok’s second full-length since 2019 opens in near darkness, “Mesmerize” pacing over murky analog bass and vinyl crackle while Loudmic’s scratch work circles like a vulture. Her delivery is measured, almost meditative, yet every internal rhyme detonates on the down-beat, turning the track into a slow-burner that refuses the dopamine rush of contemporary trap templates. Throughout, the emcee pokes at certainty itself—“Absolute truth is just a myth in this reality/Like the gender of God…” she spits on “Earthlinguist,” teasing cadence until the beat seems to hold its breath. Kanif the Jhatmaster’s beats avoid maximalism, favoring negative space and low-pass grit that recall Company Flow’s early tectonic rumble more than glossy modern boom-bap. Cambatta turns “Tessellator” into an occult cypher of syllable flips while Sa-Roc’s razor-sharp counter-flow on “The Grand Geode” feels like two griots carving hieroglyphs into the same stone in real time. A broken-time snare pattern jitters beneath guitars and swirling synth arpeggios while Blakrok spits “I bend light around my name,” collapsing cosmic physics into street-corner bravado. Rather than a victory lap, the fade-out opts for unresolved chords, implying that transcendence is a process, not a destination. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Stereolab, Instant Holograms On Metal Film

Stereolab’s first studio album in fifteen years lands as a study in continuity rather than reinvention. Tim Gane’s oscillating guitar-organ lattices still ride a motorik pulse that nods to Neu! while Laetitia Sadier’s bilingual vocals question capitalist myths with straight-edge clarity. Producer Cooper Crain broadens the palette with cornetist Ben LaMar Gay and percussionist Ric Elsworth, adding warm brass and tuned hand-drum chatter that nudge the groove toward spiritual jazz without breaking it. The rhythm section maintains its ride-cymbal glide, but the tempos breathe more, allowing Rhodes voicings to linger like vapor trails. Rather than chase novelty, the album trusts iterative nuance; small modulations in synth filter or mallet choice carry the record’s quiet argument that subtle change can still feel radical. — Oliver I. Martin

NAO, Jupiter

NAO’s fourth LP orbits joy as both theme and method, opening with “Wildflowers,” a candied slip-n-slide of syncopated bass slaps and stacked harmonies that recall the playful polyrhythms of her early EPs while injecting newfound ease. Throughout, the songwriting alternates between dance-floor rapture—“Happy People” piles rubbery Moog riffs under a chant-ready chorus—and nocturnal slow jams like “Elevate,” where clipped hi-hats tick beside pillow-soft synth pads as NAO’s soprano melts into airy head-tones. She threads cosmic symbolism—Jupiter as planet of abundance—through plainspoken declarations: “We all win /when light gets in,” she repeats over gospel-tinged stacked vocals on the mid-tempo standout of the same name. Even the ballad “Light Years” resists drift; hand-played Rhodes chords bend micro-tonally at phrase endings, suggesting gravitational wobble in the song’s astronomy metaphor. NAO’s hallmark is contrasts—helium falsetto against murky sub-bass, sugary hooks against knotty rhythm changes—and Jupiter refines that balance until it feels as natural as breathing in and out. — Tai Lawson

Butcher Brown, Letters from the Atlantic

This album unfolds like a postcard collage, as the Richmond crew melds jazz-funk muscle with house syncopation and seaside ambience. The airy miniature “Seagulls” drifts on brushed cymbals, Rhodes haze, and a trumpet phrase that arcs skyward before dissolving. Melanie Charles floats ad-libs through the breakbeat of “Unwind,” answering a restless flute line while the rhythm leans toward drum-and-bass without rushing. Yaya Bey bathes “I Remember” in neo-soul glow, stretching her phrases just behind the drums to heighten tension. “Ibiza” pivots on a four-beat clap, Corey Fonville toggling between electronic accents and a live kit to blur the lines between programmed and organic timekeeping. Nicholas Payton’s modal run on “Montrose Forest” slices through the mix yet never disrupts the ensemble’s downtempo swagger. Guitarist Morgan Burrs sticks to palm-muted motifs, allowing DJ Harrison’s synth bass to roam the harmonic landscape. Texture, not pyrotechnics, drives the session, and in that spaciousness, Butcher Brown proves breadth sounds cohesive when everyone trusts the pocket. — Reginald Marcel

John Glacier, Like a Ribbon

Between 2020 and 2021, John Glacier forged a distinctive voice amid an era of lockdowns. The album’s producers—Flume, Evilgiane, Kwes Darko, Andrew Aged, Harrison, Zack Sekoff—warp drums until they flicker like faulty streetlights, leaving Glacier’s voice to drift in and out of focus. She opens “Satellites” mumbling through reverb haze, syllables slicing the mix like paper cuts before a sudden bass surge resets the pulse. The record’s emotional anchor is “Ocean Steppin’,” where she raps, “Ocean steppin’ on shores/Crash the wave, then I pause/Bring it back to the land,” turning seascape imagery into a metaphor for psychic ebb and flow. That push-and-pull defines the sequencing: “Money Shows” smears Eartheater’s spectral co-lead across trap triple-hi-hats, then “Found” drapes half-remembered piano over clipped jungle breaks. Glacier’s deadpan delivery disguises barbed confessionals—references to “sleeping in the park ’cause the rent made no sense” land like passing thoughts, all the more devastating for their casual tone. Observers of her live sets describe the record as split into movements that mirror the ways a ribbon curls, falls and snaps back, and that metaphor tracks: energy coils tightly on “Nevasure,” slackens into ambient murmur on “Steady As I Am,” then whips up into break-beat turbulence on “Home” before settling into the whispered finale “Heavens Sent.” — Nehemiah

Damon Locks, List of Demands

This collage of spoken word, archival samples, and skeletal percussion feels both historical and urgent. The project stems from years of teaching art inside Illinois prisons, where Locks and students drafted an “Artist Constitution” celebrating narrative control. Echoes of that document surface in the title track as his processed voice repeats “control power” over tin-can snare hits. Field recordings from civil-rights marches seep into “Distance,” letting old megaphones sit beside contemporary drum machines. Minimal bass loops nod to dub poetry influences, such as Gil Scott-Heron and Linton Kwesi Johnson. Compared to his larger Black Monument ensemble, the instrumentation here is stripped down to brittle hi-hats, fractured synth stabs, and stacked vocals. Locks credits Sun Ra and Bad Brains for teaching him that dissent can be joyful, an ethos audible throughout. The lack of traditional choruses turns each track into a vignette that prioritizes tone over hook. Recurrent clipped radio voices bind the suite into a sonic archive that refuses to treat history as a mere backdrop. — Ameenah Laquita

Benjamin Booker, Lower

Booker’s gravel-gargled blues once leaned on garage-rock crunch. Here, he grafts that snarl onto hip-hop drum programming featuring distorted 808s that sit beneath jangling open chords, making “Black Opps” sound like a cassette dubbed over Public Enemy by way of Mudhoney. His vocals slide between preacher rasp and whispered self-recrimination, punctuated by sudden tape-stop stutters courtesy of producer Kenny Segal. “Pompeii Statues” compares bodies frozen in ash to communities petrified by systemic neglect, the chorus pleading, “If the world don’t move, how can a quake set us free?” Feedback squeals choke out the final word, an audible representation of stifled agency. “Rebecca Latimer Felton Takes a BBC” delivers a satirical gut punch at American white-supremacist iconography through tongue-in-cheek narrative, yet never collapses into novelty. Even the record’s brief moments of repose—finger-picked verses on “Hope for the Night Time”—swell into fuzzed-out codas, as if calm itself were under surveillance. — Brandon O’Sullivan

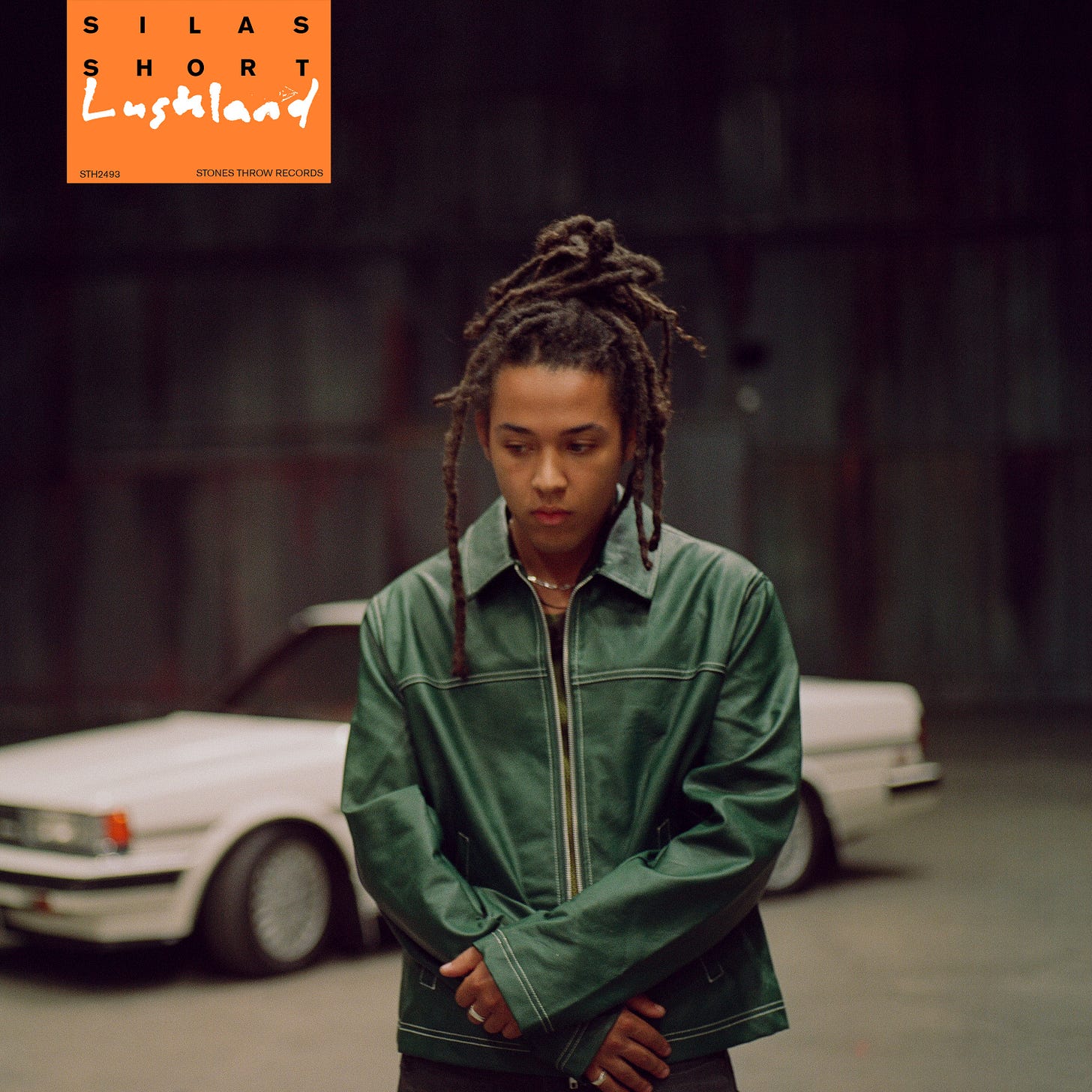

Silas Short, Lushland

Silas Short records soul music the way painters layer watercolors, featuring translucent strokes after translucent strokes until depth sneaks up on you. From opener “Justa Dream,” finger-picked electric guitar, brushed drums, and tape-echo vocals form a pocket so hushed that every string squeak counts as percussion, asserting intimacy as a compositional tool. Short’s self-described “liquid-style” guitar playing—developed after breaking a hand in his teens—lets him slide micro-intervals between chords, giving tracks like “Ph0necall” the fluid harmonic feel of early D’Angelo without the latter’s overt funk punch. The title cut swells from whispered verse into towering choir-like refrains, but he starves the snare of reverb so each hit sounds like a finger tap on a kitchen table, translating grand emotional reckoning into bedroom-studio scale. Lushland knits together tales of relocation, fear of failure, and guarded optimism; “Pass On By” croons, “Dreams ain’t cheap/But neither are regrets” over muted trumpet flourishes that fade before resolving, underscoring the record’s fascination with decisions suspended in mid-air. — Harry Brown

Lady Gaga, Mayhem

Gaga returns as ringmaster of glitter-smeared agitation, carving electropop hooks from abrasive synths while lyrics probe identity’s fun-house mirrors. “Disease” balances chipped-glass whispers against an unflinching pulse, transforming anxiety into a dance command rather than an apology. Abracadabra” vaults through two key changes, its chorus soaring on stacked harmonies even as verses flirt with industrial grit. The record’s mischievous core is “Perfect Celebrity,” a pop strut where warped piano loops frame confessions about the surreal weight of fame. Bruno Mars trades gospel-tinged call-backs with her on “Die With a Smile,” gliding over a pop-soul pocket animated by lightly overdriven guitars. “Killah” dives into dark-room techno, Gesaffelstein’s low-end rumble underscoring lyrics that turn desire into a threat. “Garden of Eden” offers chiming New Romantic synths beneath falsetto hooks, a brief oasis before the record plunges back into dissonance. No matter how turbulent the textures, melodies snap back into place, proof that chaos can be sculpted until its jagged edges glint rather than wound. — Jill Wannasa

Backxwash, Only Dust Remains

Backxwash continues her excavation of trauma, faith and trans embodiment, but here the sonic palette loosens: doom-metal guitars still roar, yet “Black Lazarus” rides a swung break-beat before detonating into double-kick mayhem while she spits, “my old friends keep on reaching out like they hearing you got demons—how?” “Wake Up” stretches to seven minutes, cycling from whispered lament to industrial blast beats and back, mirroring the lyric’s oscillation between suicidal ideation and the videogame spark of staying alive one more day. The record closes with “9th Heaven,” a dirge-turned-hymn whose organ drones crumble under distorted 808s, suggesting redemption is possible only through loud and unvarnished confession. In turning horror-rap’s aesthetics inward, Backxwash finds communion not in absolution but in the shared feedback loop of pain transmuted to art. — Brandon O’Sullivan

The War and Treaty, Plus One

Michael and Tanya Trotter composed with collaboration in mind, a spirit that animates every track. Organ and tambourine ignite “Can I Get an Amen,” signalling a gospel impulse that threads through the set. Tanya’s call-and-response against a churning guitar riff echoes the church services that shaped her delivery. “Leads Me Home” slips into a country-soul lilt, lifted by swooping fiddle lines from Omar Ruiz-Lopez. Gospel drive, blues grit, and country storytelling merge into a sound that feels timeless rather than retro. The slow-burning “Called You By Your Name” climbs from a whisper to a shout without losing its rhythmic steadiness. Its unresolved final chord invites the message to linger beyond the runtime. Plus One ultimately celebrates communal spirit, showing how two voices can harness many styles without diluting their shared identity. — Imani Raven

SPELLLING, Portrait of My Heart

Chrystia Cabral pulls her avant-pop lens inward, setting her commanding vibrato amid guitars that swing from glam swagger to shoegaze blur. “Keep It Alive” marries plucked strings to jittery electronics, its restless tempo echoing lyrics about love’s upkeep.“Alibi” hits harder, chugging riffs underpinning a defiant hook that explodes into a wah-soaked solo. “Destiny Arrives” trades distortion for crystalline synth stabs, ready for an ’80s adventure montage even as Cabral confronts fate’s heavy hand. Chaz Bear’s pastel guitar colors “Love Ray Eyes,” softening the album’s stormy edges without draining urgency. By reimagining My Bloody Valentine’s “Sometimes,” she turns shoegaze churn into a slow-burn torch song alive with wavering organ and near-breaking vibrato. That reinterpretation highlights the record’s theme, with affection distorting perception, yet clarity often emerges from within the blur. By stripping back earlier baroque ornamentation, Cabral delivers her most direct, soul-bared statement to date. — Charlotte Rochel

Chuck D, Radio Armageddon

Chuck D wields his baritone the way Coltrane used sheets of sound—layered, unrelenting, and always aimed at a higher civic purpose. Over breakbeats that crunch like smashed radios and shards of distorted acid-rock guitar, he re-stacks the Bomb Squad’s collage aesthetic into a leaner but no less combustible broadcast that ricochets between scowling funk riffs and proto-punk thrash. Cuts such as “Black Don’t Tread” and “Rogue Runnin’” bolt scratch choruses to thrumming bass, framing verses that rage against algorithmic misinformation and voter suppression with the same urgency he once leveled at Reagan-era racism. Yet the record is hardly a nostalgia trip: on “New Gens,” he cedes the spotlight to Stetsasonic’s Daddy-O and a chorus of younger MCs, threading old-school mic-command into a rolling drill-adjacent cadence that argues cross-generational solidarity is the new radical gesture. Across the album’s “station breaks,” hard-panned sirens, Black radio idents, and shortwave static create the illusion you’re spinning a dial through the apocalypse—only to land, again and again, on a voice that refuses to yield. — Phil

Tanika Charles, Reasons to Stay

Tanika Charles sings like she’s opened every wound just wide enough for the groove to cauterize it. Her fourth LP trades previous rom-com heartbreak narratives for familial fault-lines, stacking Chi-Lites-style string swells and clipped hi-hat shuffles against lyrics that name-check abandonment, reconciliation, and inherited shame with unflinching clarity. “Don’t Like You Anymore” drapes smoky B-3 chords over a head-nodding pocket, her phrasing dipping into husky low notes before vaulting into a trembling melisma that cracks exactly where the story does. Producer Scott McCannell and mixer Kelly Finnigan infuse every rim-click and tambourine shake with analog hiss and ribbon-mic saturation, lending mid-tempo burners like “Talk to Me Nice” the warm, vintage sound of a lost 1973 acetate without ever sounding like a costume. When Clerel’s smoky tenor enters on the Gamble-and-Huff-tinged “Win,” the arrangement briefly slips into woozy psychedelic gospel before returning to its neo-soul core—a reminder that Charles, even in her most vulnerable confessions, never lets the pocket drift. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Knowledge the Pirate & Roc Marciano, Round Table

Roc Marciano’s loops here barely clear the noise floor—hushed Rhodes phrases, brittle snare taps, leaving Knowledge’s gravelled baritone to fill the frame. Opening salvo “Eating Etiquette” reimagines fine-dining manners as codes for dope-game discretion; lines about “forks and knives” resurface later as metaphors for friends who cut both ways. The lone posse moment, “The Outfit,” finds Roc himself stepping from behind the boards to swap weary boss talk in eight-bar bursts, the pair sounding like chess partners mid-match rather than rivals. Across the album Knowledge revisits maritime lore—“Addicted to Danger” compares a cracked hull to a bruised ego, and closes on “Receipts,” a recounting of debts paid in blood that fades under creaking ship-rope samples, tying the crime narratives back to the title’s code of honor. — Javon Bailey

Brother Ali, Satisfied Soul

Brother Ali’s first full-length since Love & Service opens with a prayer, then sweeps forward on verses that fuse mystic awe with street-level witness. The title song’s refrain (“My mouth is a fire starter/My eyes spout water/My body in the drama”) sits at the heart of the record, a mantra that frames rhetorical ferocity as a tool of healing rather than domination. Throughout, Ali raps not to broadcast credentials but to excavate contradictions: compassion under siege, devotion tested by ego, hope flickering inside structural violence. Mid-album passages linger on family—he invokes his daughter and late father in the same breath, suturing generational grief to a vow of stewardship. His imagery retains the tactile immediacy that marked Shadows On the Sun, yet the tone is lighter, almost serene; he has traded the blunt protest of “Uncle Sam Goddamn” for contemplative lines that treat justice work as lifelong ritual, not campaign slogan. When he cautions “the only person that can injure me is my own self,” the epiphany lands without self-help platitudes because the verse has already shown the cost of letting anger curdle into dogma. While Ant’s drums still boom in the low end, the beats leave space for Ali’s cadence to rise and fall like spoken-word recitation rather than strict sixteen-bar form. — Javon Bailey

MIKE, Showbiz!

MIKE threads his voice through tape-warped soul snippets that feel rescued from half-remembered afternoons; the sequence rushes by in miniature vignettes, most under two minutes, yet each one lands like a Polaroid of a mood you once thought was private. He constructs nearly the entire sound-bed himself under the DJ Blackpower alias, layering sub-bass, brittle drums, and stray gospel hums until the surface crackles like old acetate The brevity isn’t gimmickry as it mirrors the scribbled-in-transit quality of his writing, a stream of consciousness that moves from grief to gratitude without warning. On “Watered Down,” a single line—“That’s my sister, treat her like my daughter, really”—condenses a family history into ten words, then dissolves into a woozy Rhodes run that never resolves. Moments later, the beat switch in “What U Bouta Do?/A Star Was Born” opens space for 454’s helium blur, underscoring how camaraderie interrupts MIKE’s interior monologue just long enough for sunlight to leak in. — Harry Brown

Kali Uchis, Sincerely,

Framed as a box of unsent letters, Sincerely threads bilingual confessionals through slow-motion soul arrangements whose edges blur like ink on vellum. “Heaven Is a Home…” eases in with Sunday-service organ before cavernous half-time drums and stacked choir harmonies suggest the solitude of prayer rather than the pomp of gospel. “Sugar Honey Love” lifts a doo-wop progression then melts it beneath Mellotron flutes while Kali Uchis sings, “You put the blood back to my heart,” an image that turns romantic sweetness into literal resuscitation. Mid-sequence ballad “For: You” floats on vinyl crackle and muted strings; the vocal barely rises above a whisper, transforming grief into a lullaby instead of a lament. Volt-switch “Daggers!” slams distorted synth-bass against break-beat clatter, her doubled vocal riding inside the beat rather than above it, as if anger itself is trapped in that buzzing low end. “Breeze!” resolves the cycle with brushed drums and nylon-string guitar that fade into room tone, mirroring the way loss never entirely disappears—it just becomes another current of air moving through the day. — Charlotte Rochel

Panda Bear, Sinister Grift

Noah Lennox glides between sun-bleached psych-pop and knotty introspection, pairing stacked harmonies with drum programming that smacks like hand-claps recorded in an empty hallway. Bright guitar strums shimmer over skipping percussion in “Praise,” giving the record an almost hymn-like greeting while the lyric circles back to lingering doubt. His Lisbon studio becomes another performer; faint gull cries and floorboard creaks slip into the stereo field, blurring ambience and melody. 50mg” pulls a rubbery bass figure from dub tradition, then offsets the groove with twangy slide guitar so the song feels buoyant and woozy at once. “Ferry Lady” slows the pulse with Mellotron chords that crest like soft surf, foregrounding a vocal stack so dry every breath lands in focus. “Venom’s In” flips that serenity; Lennox strips most of the reverb and lets the lyric land bare, exposing post-heartbreak fatigue. Cindy Lee hovers through “Defense,” shadowing the melody an octave up until distorted guitars surge beneath them and hint at guarded relief. Silence carves pockets around loops and choruses, so each spectral detail feels earned. The result is Panda Bear’s most emotionally transparent set in years, a record that treats vulnerability as a destination rather than a detour. — Charlotte Rochel

duendita, A Strong Desire to Survive

Queens vocalist-producer duendita distills trauma, healing and righteous anger into a ten-song set. Field-recorded subway rumbles and detuned upright-piano chords underpin opener “Why I Didn’t Report,” where her caramel alto floats above clipped news-broadcast samples to confront assault silence culture. Throughout, she toggles between choral stack-ups worthy of Renaissance polyphony and skeletal piano ballads like “Baby Teeth,” recorded in her bedroom with a single Zoom mic. She self-produces most tracks, but MIKE slips in lo-fi drum palettes on “HTP,” echoing their New York DIY lineage. The album’s sequencing feels nonlinear—short interludes bleed into full-length songs, mirroring the circular nature of recovery. By the closing voicemail collage “All Mine — June 11, 2019,” she reframes survival not as a destination but perpetual motion, each track a checkpoint in reclaiming bodily autonomy. — Jamila W.

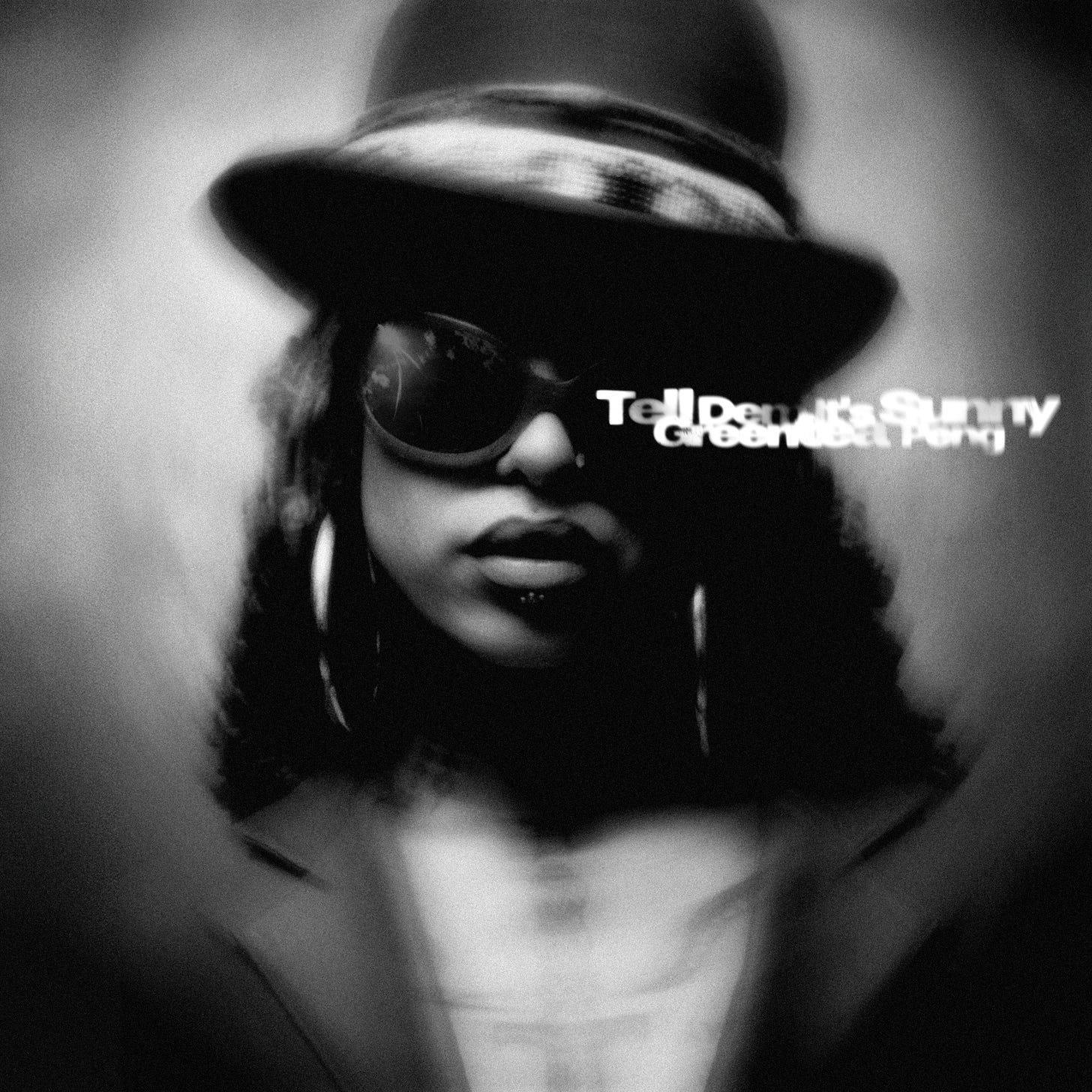

Greentea Peng, Tell Dem It’s Sunny

Recorded largely in 432 Hz, Peng’s sophomore LP feels like sun-drenched street gospel sung through a kaleidoscope. “Tardis (Hardest)” drapes her husky contralto over a strutting dub bass-line and skittering rim-shots, the song’s time-travel metaphor doubling as an invitation to detach from linear thinking and sink into groove. “My Neck,” co-produced by South London experimentalist Wu-Lu, folds lo-fi hip-hop drums into flanged guitar echoes, bridging the earthy and the astral without resorting to New-Age vagueness. Even quieter pieces such as “Raw,” built on finger-picked acoustic chords and barely there upright-bass—carry gentle psychedelic swirl in the background, suggesting that clarity and cloud-haze can coexist. Peng writes in mantra-length phrases, often repeating lines until they loosen their semantic grip and become breath themselves; the effect is meditative but never sleepy, because the rhythm section keeps feet tethered to pavement even as minds arc toward cosmos. If her debut chronicled inner turbulence, Tell Dem It’s Sunny is the exhale after the storm: not naïve bliss, but cultivated brightness that accepts shadow as teacher. — Jamila W.

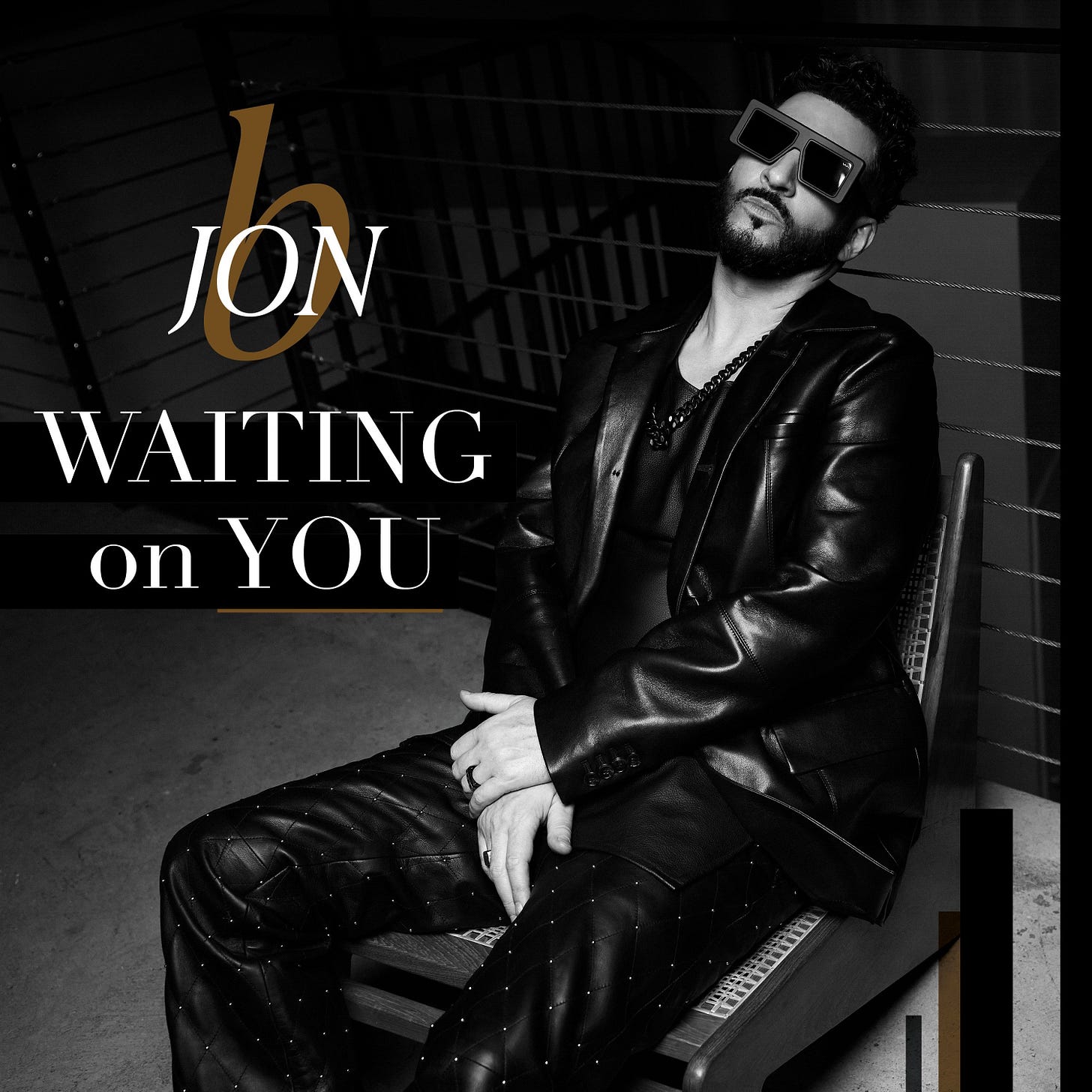

Jon B, Waiting On You

Jon B returns after more than a decade with an album that sounds like a seasoned songwriter revisiting his ‘90s blue-eyed-soul blueprint but sanding off the youthful bravado. The title track, a duet with Tank, glides on a finger-picked guitar loop and rim-click drums, its hook expanding into radiant stacked harmonies that nod to Donny Hathaway without feeling retro. He leans heavily on live instrumentation: “Still Got Love” rides a rolled-off-hi-hat groove reminiscent of “They Don’t Know,” yet the chord changes are richer, letting his tenor linger around suspended ninths before resolving into velvet cadences. Jon’s pen stays understated; on “Natural Drug,” he sketches intimacy as euphoric addiction, his falsetto flipping into chest voice just as the Rhodes vamp modulates up a half-step—a subtle signal of desire escalating. Alex Isley’s cameo on “Show Me” introduces a feathery counterpoint: her airy harmonies float over brushed snares while Jon lays down guttural ad-libs, framing the duet as a soft-loud dialog rather than a simple trade-off. Waiting On You never chases trends; instead, it updates Jon B’s classic palette with deeper harmonic pockets and lyrics steeped in grown-folks patience. — Tai Lawson

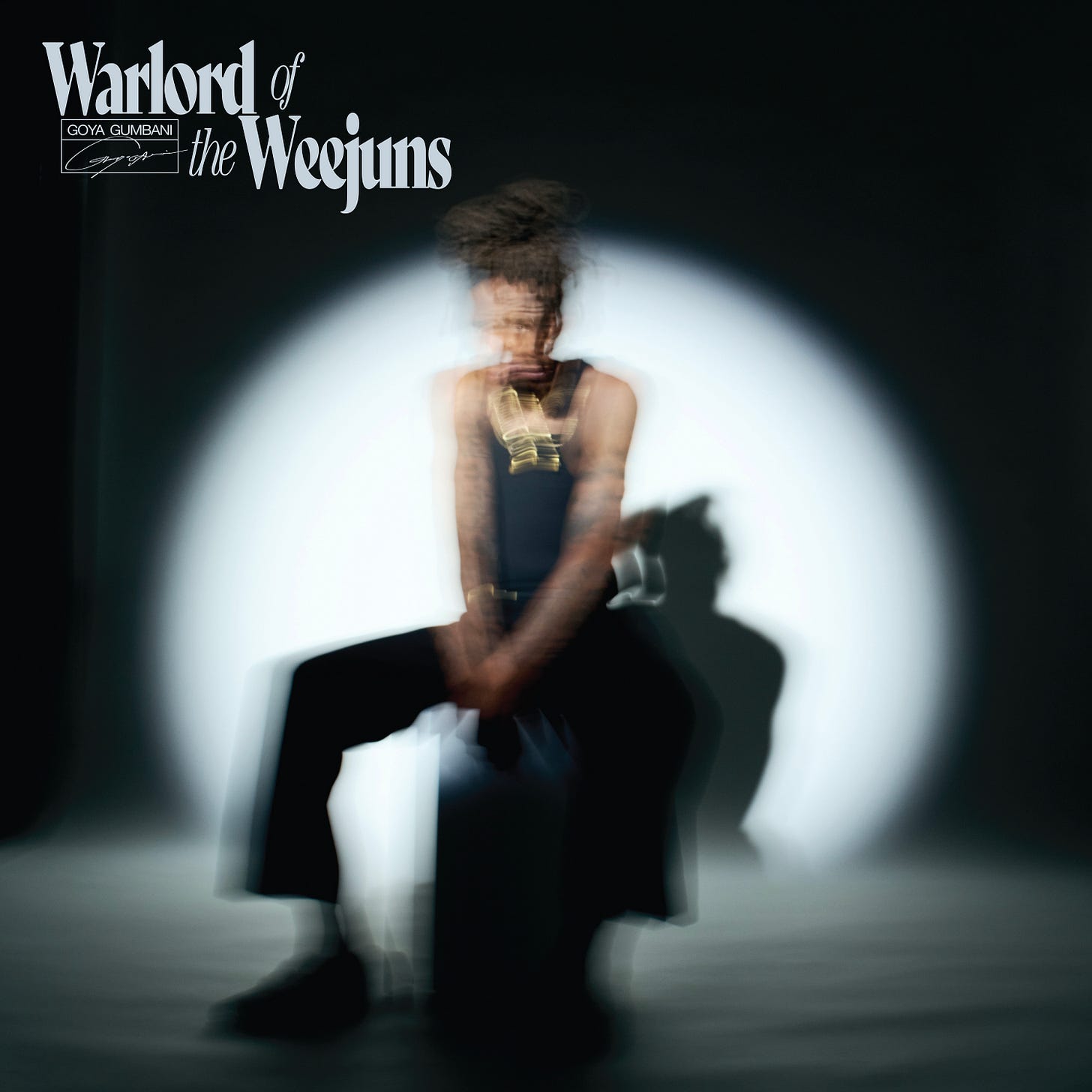

Goya Gumbani, Warlord of the Weejuns

Gumbani keeps the tempos unhurried, letting brushed drums, upright bass strolls, and Joe Armon-Jones’s keys breathe like late-night club smoke. The opening statement “Beautiful Black” slides between hymn and self-portrait, his voice almost conversational as he insists on radiance in every bar. When lojii joins him on “One Hand Washes the Other,” the verses fold generosity into creed: each line feels hand-stitched, no seams showing. The album peaks during “Chase the Sunrise,” where Fatima’s soprano flutters above woodwind flourishes, turning a simple pursuit of peace into a communal sunrise service. Across sixteen tracks, the rapper’s Brooklyn drawl and London cool blur; you catch Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word cadence one minute, Mic Geronimo’s sneak-rhythm phrasing the next, yet the center never wobbles because his writing—half prayer, half diary—keeps circling back to dignity and everyday faith — Randy

Coco Jones, Why Not More?

Coco Jones scales up from breakout EP to full-length with a record that moves like a big-budget romance film where wide stylistic shots, tight emotional close-ups, and a clear through-line of self-possession. The title track taps YG Marley for a syncopated reggae swing, but Jones centers her honeyed alto, flipping from melismatic runs to clipped patter as she questions why mutual devotion ever needs justification. “Taste” flips the iconic “Toxic” acapella into a stop-start trap pattern; rather than coasting on nostalgia, Jones re-pitches the riff into a minor key and sings against it, turning a familiar melody unsettling and seductive at once. Coco toggles between lush, late-’90s vocal stacking (“Here We Go (Uh Oh)”) and sleek, atmospheric Pop&B (“By Myself”), but the production (handled by Stargate, London On Da Track, and Jasper Harris) never overwhelms her phrasing. Instead, she uses each beat to show new facets: a scratch in the voice on a climactic high note, a whispered ad-lib tucked behind the three-and-one. Coco Jones is proving she can inhabit any R&B landscape without losing the tactile warmth that made “ICU” a breakout moment. — Tai Lawson

Derya Yıldırım & Grup Şimşek, Yarın Yoksa

Anatolian folk modes meet woozy psych-soul, anchored by Yıldırım’s bağlama lines that twist through microtonal bends. “Çiçek Açiyor” lays a rolling bass riff beneath her falsetto, letting the hand-drum shuffle keep the groove buoyant. Flute and organ entwine across “Cool Hand,” nudging the rhythm toward samba sway without abandoning Anatolian cadence. The traditional standard “Hop Bico” reemerges with fuzz-guitar stabs and a backbeat that turns a village melody into garage-psych delirium. “Direne Direne” channels protest energy, chants rising over a climbing groove that makes resistance sound celebratory as well as defiant. Producer Leon Michels favors analog immediacy, leaving string squeaks and clap-backs in the mix so every track breathes like a stage performance. The a cappella opening of “Misket” freezes time, Yıldırım’s unaccompanied voice turning folk lament into quiet thunder. When “Güneş” swells on Mellotron chords, the record hints at dawn rather than dusk, answering its title’s fatalist question with radiant after-glow. — Harry Brown