The Best R&B Album, Every Year Since 1957

Followed by examining the voices that defined the ‘60s, the breakthroughs of the ‘70s, the reinventions of the ‘80s, the experiments of the ‘90s, and the digital age continue into the new millennium.

R&B artists have continuously reshaped their craft for more than six decades, blending deep-rooted vocal traditions with shifting production methods to reflect changing social and cultural conditions. Beginning in 1957, this column selects one defining R&B album per year and arranges them chronologically to illustrate a genre that has never stopped adjusting its contours.

The featured albums range widely in style and intent, from the earliest studio recordings to more contemporary digital releases. Rather than focusing solely on fame or popularity, the approach favors records that reveal how R&B’s recorded history evolved, capturing subtle developments and undeniable turning points.

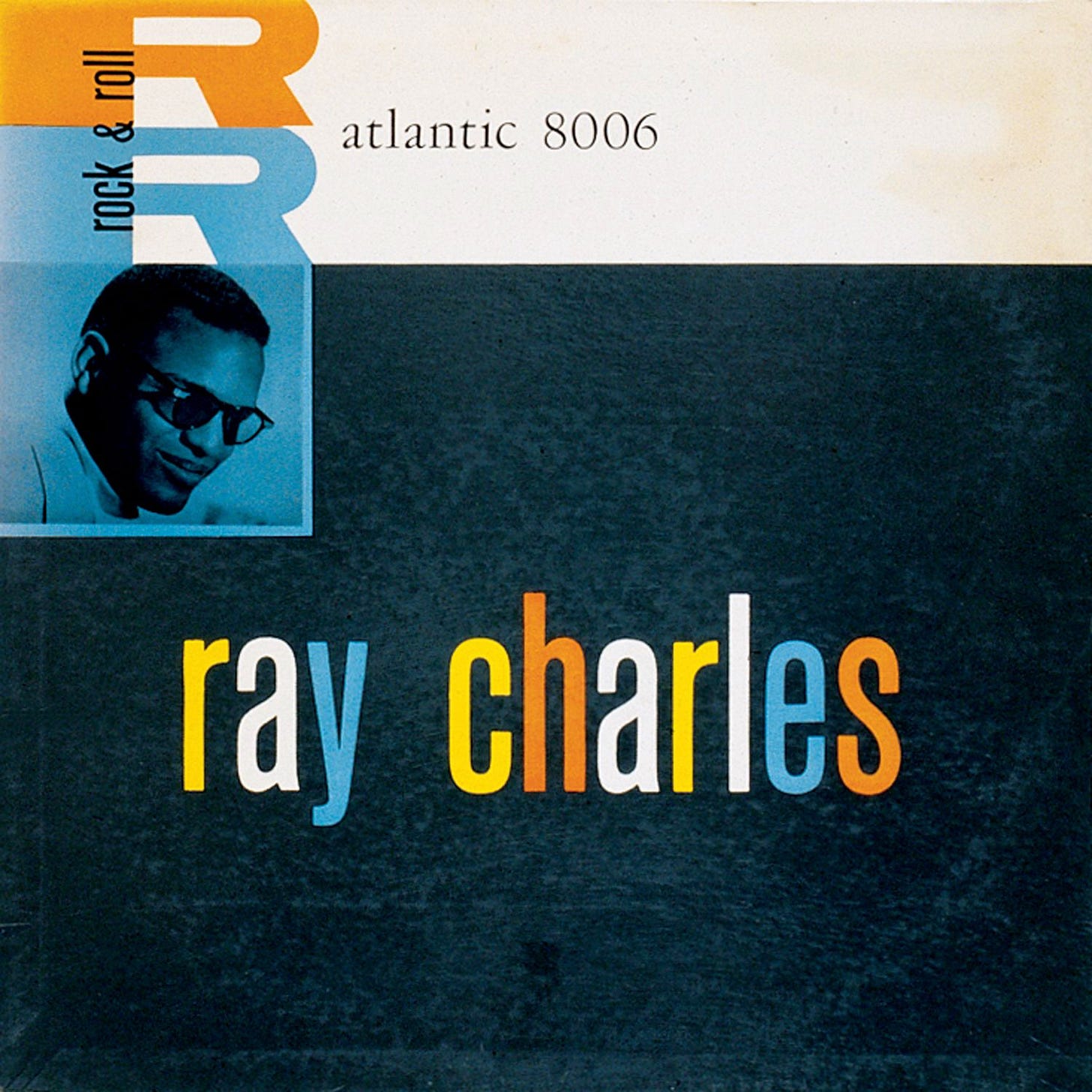

1957: Ray Charles, Ray Charles (1957)

Between the grooves of Hallelujah I Love Her So, aka self-titled, Ray Charles crafted a musical blueprint mixing original compositions with reimagined standards. His keyboard work on “Mess Around” punctuates the rhythmic foundation, while his vocals stretch from playful asides to gospel-influenced declarations. Charles brought new dimensions to borrowed material by transforming “Sinner’s Prayer” through nuanced piano phrases and emotional depth. The collection’s second half maintains momentum through arrangements highlighting his distinctive piano style—from rollicking bass patterns to delicate upper-register runs. Each selection reveals different aspects of his musical personality, whether through composed originals or personalized interpretations.

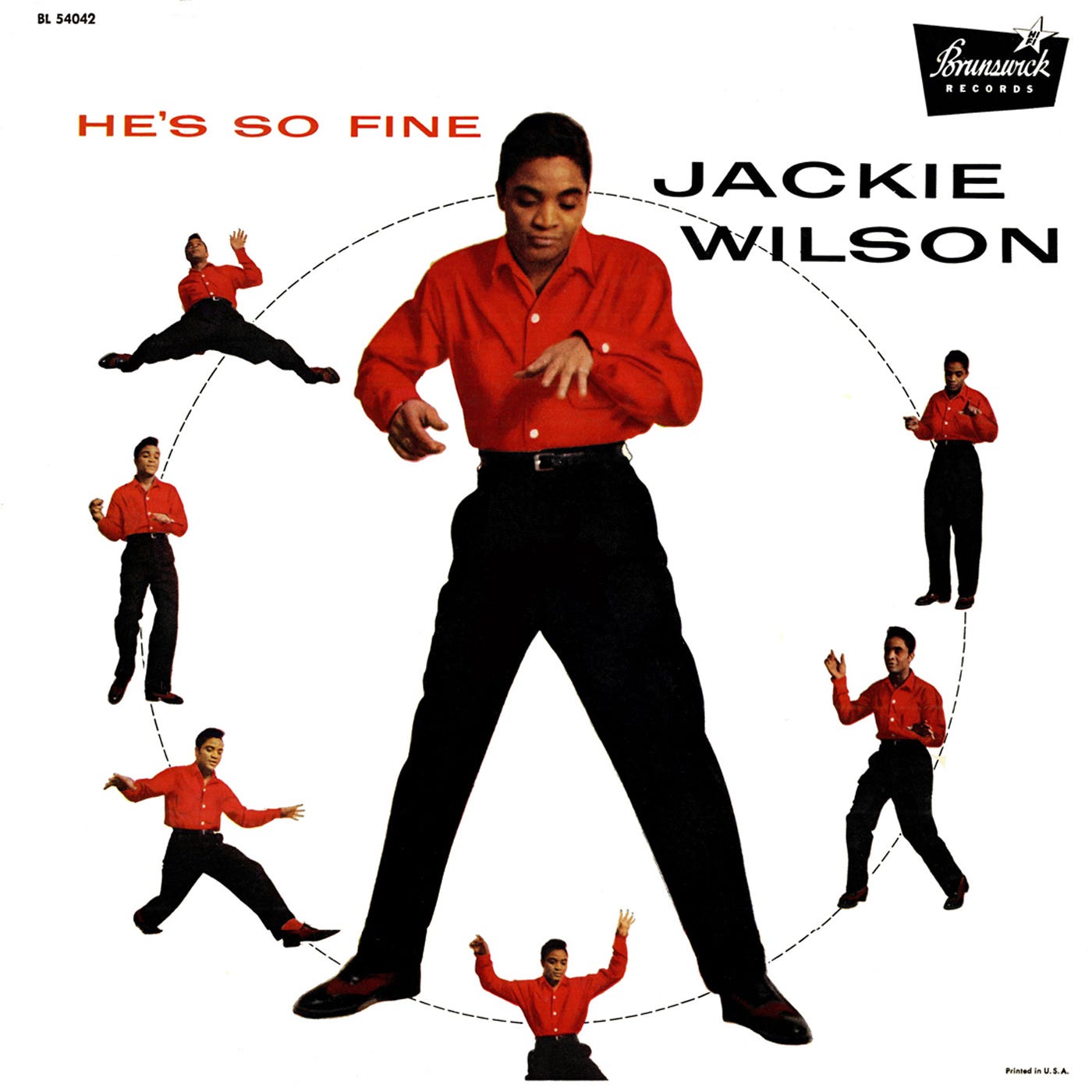

1958: Jackie Wilson, He’s So Fine

Following his exit from the Dominoes in 1957, Jackie Wilson launched his solo debut on Brunswick Records a year later. The album features six tracks penned by the songwriting duo of Berry Gordy, Jr. and Tyran Carlo (alias Billy Davis). Wilson’s rendition of “Reet Petite” with big-band accompaniment displays his impressive vocal range and energetic style. Although “Etcetera” takes a similar route, it lacks the same impact. The ballads “To Be Loved” and “Danny Boy” are delivered with grace and genuine feeling. Wilson contributed “Come Back to Me,” but it comes across as a rather uninspired, upbeat tune.

1959: Ray Charles, The Genius of Ray Charles

Ray Charles starts the program by uniting his prominent band members with Count Basie and Duke Ellington ensemble musicians. With six songs arranged by Quincy Jones, he delivers memorable performances of “Let the Good Times Roll” and “Deed I Do.” The music is highlighted by solos from tenor saxophonist David “Fathead” Newman, trumpeter Marcus Belgrave, and Paul Gonsalves on tenor sax for “Two Years of Torture.” The program’s second half features six ballads, with Charles accompanied by a string orchestra arranged by Ralph Burns. His vocal mastery shines on tracks like “Come Rain or Come Shine” and “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Cryin’,” bringing a soulful touch to timeless standards.

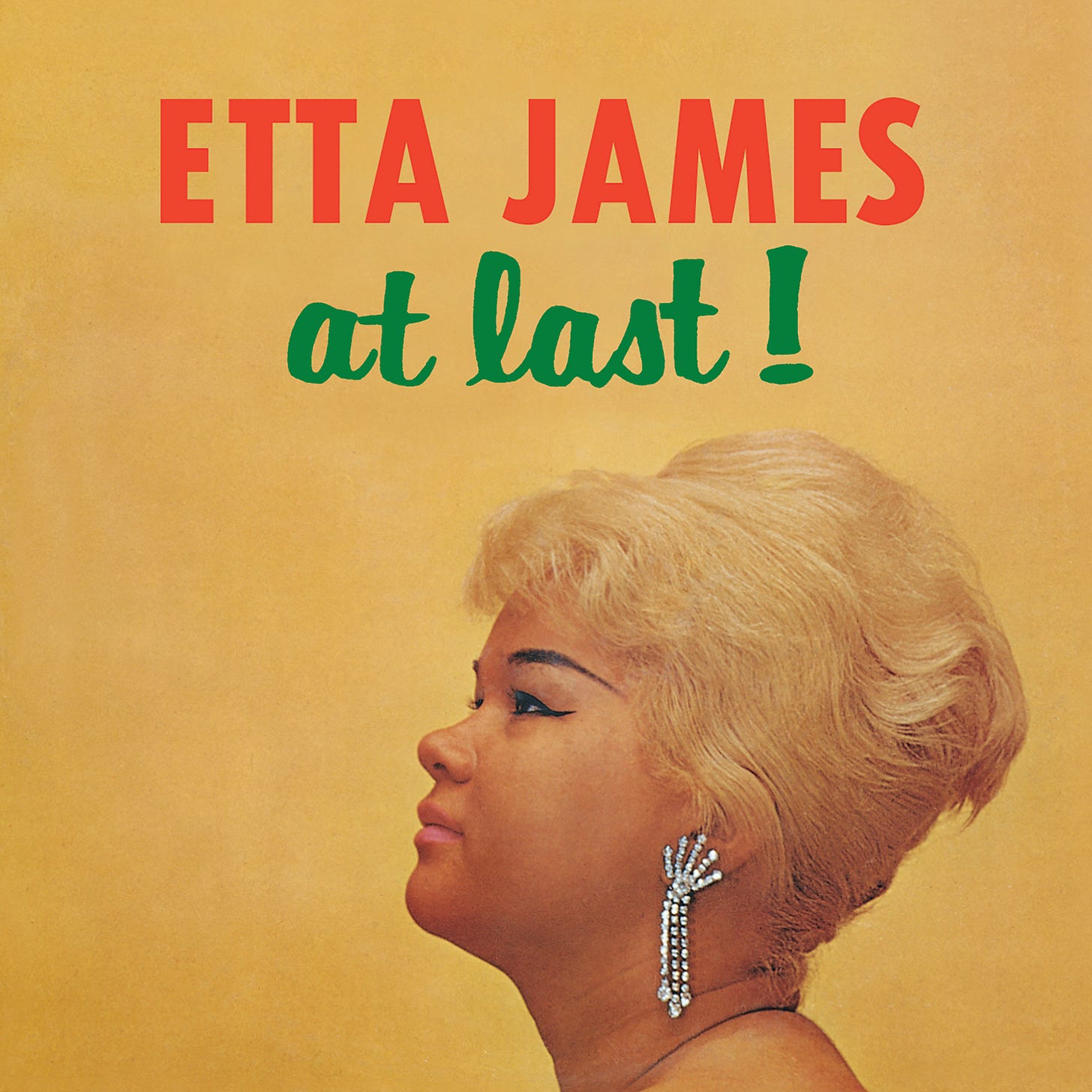

1960: Etta James, At Last!

Etta James reentered the spotlight with her first Chess album, At Last, after several years following her initial R&B hits “Dance With Me, Henry” and “Good Rocking Daddy.” The album placed her on both R&B and pop charts with tracks like the title song, “All I Could Do Was Cry,” and “Trust in Me.” The strength of At Last lies in its diverse material alongside its hits. James delivers remarkable versions of jazz standards such as “Stormy Weather” and “A Sunday Kind of Love” and brings her style to Willie Dixon’s blues piece “I Just Want to Make Love to You.” On the title track, she demonstrates impressive versatility, transitioning smooth, powerful blues vocals to light, airy nuances; her gritty, Ruth Brown-inspired growl adds depth to the performance. Although she later gained more acclaim with songs like “Tell Mama,” At Last presents James at a high point, offering a vibrant mix of blues, R&B, and jazz classics.

1961: The Miracles, Hi, We’re the Miracles

Making a strong entrance, The Miracles’ first album showcases flawless vocal talents, inventive songwriting, and an emotive romantic vibe. “Shop Around” gained significant attention as the hit single, Still, the album also features a reimagined “Way Over There,” enriched with a more captivating arrangement that foreshadowed Phil Spector’s “pop symphony” productions with groups like the Crystals, Darlene Love, the Ronettes, and Tina Turner. Smokey Robinson was the driving force behind nearly all the tracks, writing solo or co-writing with Berry Gordy or Ronnie White—all songs are exceptional, with the delicate Robinson-White piece “Heart Like Mine” highlighting the album’s appeal. While their later works became more sophisticated, the youthful spirit of Robinson, Claudette Rogers Robinson, Ronnie White, Bobby Rogers, Pete Moore, and Marv Tarplin on these tracks makes this album essential for any fan, even those who casually enjoy their music.

1962: Ray Charles, Modern Sounds In Country and Western Music

With Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Ray Charles disrupted genre conventions and reshaped the music landscape. At the peak of his career, he daringly reimagined country songs through his jazz and soul perspective. Rather than simply covering these tunes, he aimed to create a sound that embodied universal American music. He approached the songs as adaptable, adding his unique style and arranging them to engage a broad audience. The album’s production, featuring orchestral elements and backing vocals, might seem unusual today, but it was an intentional strategy to connect country, soul, and mainstream listeners. Charles’ genius shone in his ability to discern and highlight the shared emotional heart of country and blues.

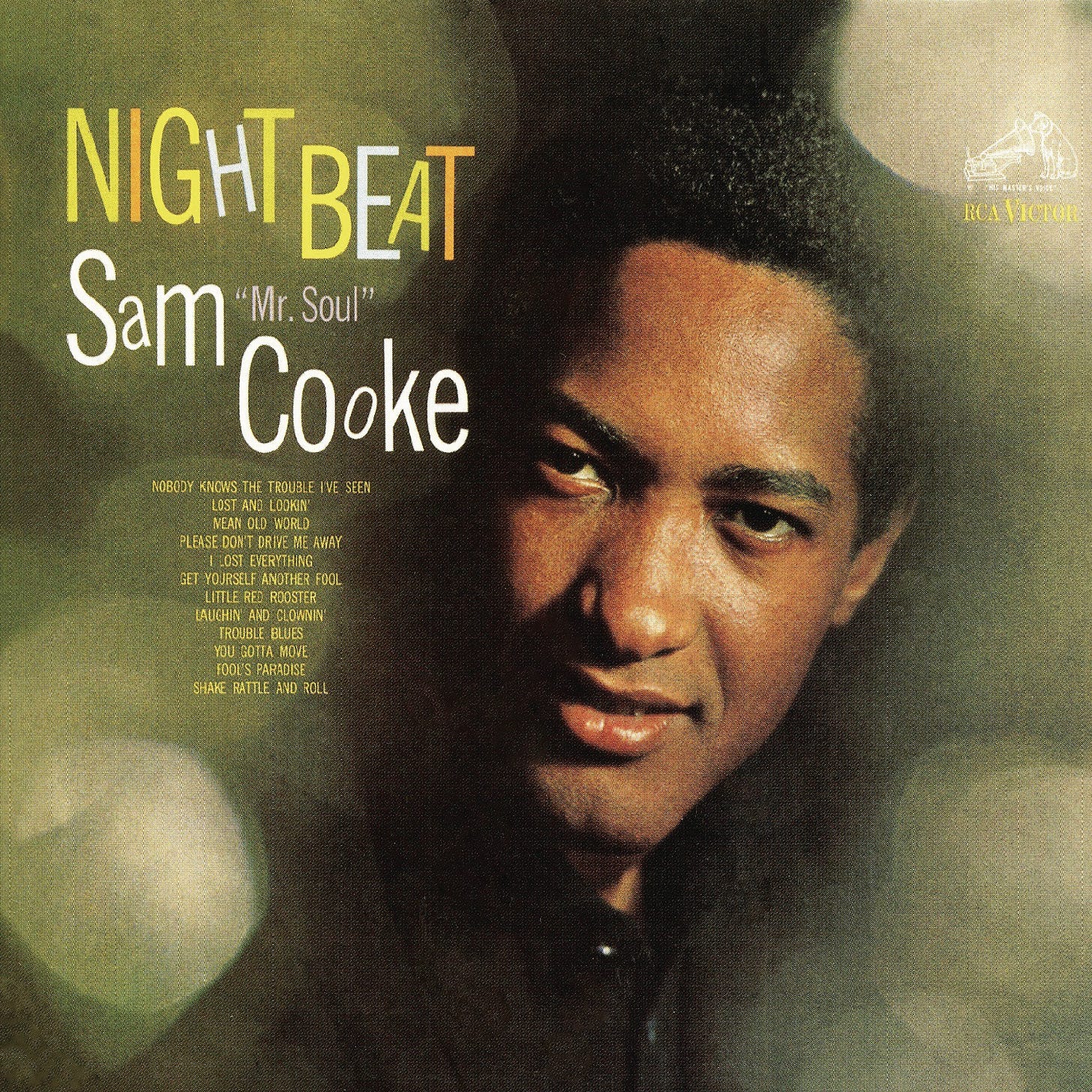

1963: Sam Cooke, Night Beat/James Brown, Live at the Apollo

In February 1963, Sam Cooke recorded an intimate session in Los Angeles with a quartet of experienced studio musicians. Departing from his usual solo work adorned with soaring strings and vocal choruses for mainstream appeal, this session placed his magnificent voice at the forefront. The musicians provided a minimalist backdrop, allowing Cooke’s vocals to shine without distraction. For example, on “Lost and Lookin’,” he’s nearly unaccompanied—only faint bass and cymbals support him, highlighting the depth of his performance. Night Beat is an opportunity to fully appreciate one of the century’s most remarkable voices outside his earlier work with the Soul Stirrers. The album features intimate blues tracks, paced like a leisurely nighttime walk.

Despite the potentially somber themes and slow tempos, Cooke’s voice is so uplifting that it defies any sense of gloom. He contributed three original songs, including the outstanding “Mean Old World,” and offered a fresh arrangement of the traditional “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.” Venturing into jump blues, Cooke brings genuine grit to “Little Red Rooster” and adds an uptown swing to “Shake, Rattle and Roll.” The session highlights individual talents, like Barney Kessel’s unembellished guitar solo on “Get Yourself Another Fool” and Billy Preston’s playful organ on “Little Red Rooster.” If Cooke had lived longer, more sessions like this might have been possible, but Night Beat remains a treasured rarity in his catalog.

In a performance that became legendary, James Brown and The Famous Flames ignited the Apollo Theater. Opening with “I’ll Go Crazy,” Les Buie’s sharp guitar riffs and the lively horn section immediately drew the audience into the experience. Brown’s passionate vocals, harmonizing with Bobby Byrd, Bobby Bennett, and “Baby” Lloyd Stallworth, delivered a strong message of independence central to his music. They were seamlessly transitioning to “Think,” the band showcased their impressive speed and endurance, reflecting the dynamic energy they shared with the crowd. Slowing things down, they introduced “I Don’t Mind,” a blues number where Brown’s seductive delivery and the angelic backing vocals captivated listeners. The intensity grew with “Lost Someone,” a ten-minute soulful ballad rich in emotion featuring Lewis Hamlin’s precise trumpet work that honored Count Basie while creating a fresh sound.

To keep the audience engaged, The Flames presented a well-paced six-minute medley of their hits, including two performances of “Please, Please, Please,” as well as “You’ve Got the Power” and “Why Do You Do Me.” The crowd’s enthusiasm mirrored the band’s cheers, matching Clay Fillyau’s powerful bass drum. The evening they were peaked with “Night Train,” Brown’s latest hit, with everyone moving to its infectious rhythm and city roll call. This performance demonstrated Brown’s relentless drive for perfection, complex rhythms, and the band’s ability to maintain sharp focus amid escalating excitement. The Live at the Apollo album captured this landmark in soul music, showcasing James Brown’s unmatched showmanship and The Famous Flames’ exceptional talent. This recording from that remarkable night continues to influence musicians and fans alike, solidifying James Brown’s title as the Godfather of Soul and affirming Live at the Apollo as an indispensable part of music history.

1964: The Temptations, Meet the Temptations

Compiling their early singles, The Temptations’ debut LP—released three years into their Motown tenure—features the hit “The Way You Do the Things You Do.” This album reflects their growth and the hands of various producers shaping their sound. “Oh, Mother of Mine” and “Romance Without Finance,” produced for the Miracle label by Andre Williams and Mickey Stevenson, spotlight Paul Williams and Eddie Kendricks sharing vocals, combining lively doo-wop with soulful nuances. Only on “The Way You Do the Things You Do” does David Ruffin appear, recorded after he succeeded Elbridge “Al” Bryant. Berry Gordy and Smokey Robinson’s tracks, including “Paradise” and “Isn’t She Pretty,” bear influences from acts like the Four Seasons and the Isley Brothers. “Check Yourself,” an original by the group and produced by Gordy, features Paul Williams’ expressive singing and unexpected tempo changes.

1965: Otis Redding, Otis Blue: Otis Redding Sings Soul

Between the grooves of Stax/Volt recordings, 1965 manifested an artistic breakthrough when Otis Redding channeled his admiration for Sam Cooke into transformative interpretations. His versions of “A Change Is Gonna Come” and “Shake” established themselves as fundamental pieces of American soul music, while his treatment of “Wonderful World” revealed fresh aspects of Cooke’s songwriting craft. After Mick Jagger and Keith Richards composed “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” as an homage to Redding’s approach, he reconstructed it with Memphis musicians’ expertise. On “Rock Me Baby,” Steve Cropper’s guitar shifts between subtle phrases and intense solos, complemented by Wayne Jackson and Gene Miller’s trumpet arrangements alongside Andrew Love and Floyd Newman’s saxophone work. Though “Respect” found a second life in Aretha Franklin’s subsequent recording, Redding’s original version showcases his rhythm and blues foundations. His interpretations of “My Girl” and “You Don’t Miss Your Water” demonstrate his skill at reimagining established songs with personal conviction.

1966: Otis Redding, Complete & Unbelievable: The Otis Redding Dictionary of Soul

Inside Memphis’ Stax Records studio, Otis Redding’s fifth album mixed gutbucket soul with ambitious song selections. His gruff baritone reimagined “Try a Little Tenderness” as an escalating soul confession, backed by the Memphis Horns’ precise brass arrangements and Booker T. & the MG’s subtle rhythmic shifts. Each note of “Day Tripper” underwent a Southern reconstruction, stripping away the Beatles’ original sarcasm. His reading of “Tennessee Waltz” demonstrated musical versatility, while originals like “My Lover’s Prayer” and “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa (Sad Song)” captured raw conviction. His last completed solo studio work proved his artistic expansion predated his famous Monterey Pop Festival set.

1967: Aretha Franklin, I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You

Jerry Wexler’s production expertise unleashed Aretha Franklin’s full artistic potential on I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You. Beyond the revolutionary “Respect,” each track reveals Franklin’s masterful command of soul expression. The Muscle Shoals ensemble provides precise musical foundation, allowing her interpretative abilities to shine throughout. Her readings of Ray Charles and Sam Cooke classics rival the source material, while her original songs—“Don’t Let Me Lose This Dream,” “Save Me,” and “Dr. Feelgood”—showcase her songwriting acumen. This Atlantic debut crystallized Franklin’s artistic identity, establishing an abiding blueprint for soul music.

1968: Aretha Franklin, Lady Soul

On Lady Soul, Aretha Franklin’s recording sessions yielded performances that exceeded her debut’s promise. The Sweet Inspirations’ harmonies weave through “Chain of Fools,” their voices answering Franklin’s lead while Joe South adds sharp, blues-tinged guitar phrases. “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” born from Jerry Wexler’s suggested title to songwriters Gerry Goffin and Carole King, pairs Ralph Burns’ ascending string arrangements with Franklin’s measured-to-mighty vocal progression. Her interpretation of James Brown’s “Money Won’t Change You” maintains its rhythmic essence while introducing call-and-response elements. The slower tempo for Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Ready” allows Arif Mardin’s brass sections to support Franklin’s methodical build, from quiet verses to full-voiced choruses.

1969: Roberta Flack, First Take

Through masterful interpretations and genre synthesis, Roberta Flack’s First Take united soul, jazz, and folk sensibilities in 1969. Her reimagining of Leonard Cohen’s “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” established an artistic blueprint that paralleled Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks in philosophical depth. Each arrangement unfolded with calculated restraint, particularly evident in her transformation of “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” into a meditation on romantic devotion. Musical elements borrowed from Miles Davis enriched “Tryin’ Times” while addressing contemporary social upheaval. “Ballad of the Sad Young Men” spoke volumes about Vietnam-era inequities, especially regarding draft policies affecting minority communities.

1970: Curtis Mayfield, Curtis

Breaking from The Impressions, Curtis Mayfield crafted an album that revolutionized soul music’s scope in 1970. His masterful production incorporated lavish orchestration while maintaining R&B’s emotional core, exemplified in “Move On Up’s” ascending brass arrangements. The social consciousness permeating tracks like “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Down Below We’re All Going to Go,” which peaked at number three, merged seamlessly with sophisticated instrumental textures, notably the crystalline harp passages in “Wild and Free.”

1971: Marvin Gaye, What’s Going On

Through What’s Going On, Marvin Gaye transformed from an R&B idol to a social commentator, revolutionizing soul music’s landscape. His brother’s Vietnam service sparked authenticity throughout the compositions, while urban deterioration, ecological damage, and civil unrest shaped the album’s message. Despite Motown’s commercial preferences, Gaye’s artistic convictions prevailed, yielding an unprecedented musical achievement. The compositions abandoned the label’s singles-focused approach, constructing an interconnected narrative. Beneath mellow arrangements, The Funk Brothers’ musicians expressed themselves freely, crafting sumptuous basslines and polyrhythmic percussion. Gaye’s production acumen captured spontaneous musical moments, while his vocals articulated anguish and optimism. His artistic choices challenged Motown’s established formulas, introducing jazz-influenced arrangements that broadened soul music’s possibilities.

1972: Al Green, I’m Still In Love With You

Under Willie Mitchell’s production guidance, I’m Still In Love With You builds upon the amorous blueprint of Let’s Stay Together yet charts its sophisticated path. This album assumes fresh dimensions between the measured arrangements and Al Green’s masterful interpretations. His bold adaptation of Kris Kristofferson’s “For the Good Times” signals an unexpected foray into country territory, while his unhurried reimagining of “Oh Pretty Woman” unearths hidden nuances in Roy Orbison’s classic. “Love and Happiness” demonstrates Green’s rhythmic ingenuity through its calculated percussion entrance, complementing the title track’s cunning melodic construction. Each selection of this masterwork contributes essential elements that rival the artistic heights of Call Me.

1973: Stevie Wonder, Innervisions

Through Innervisions, Stevie Wonder crafted an album that altered 1970s popular music, particularly instantiated in “Living for the City.” His masterful manipulation of the room-sized TONTO synthesizer system manifested groundbreaking compositions that chronicled Black American narratives during the Great Migration. Recording almost exclusively solo, Wonder’s autodidactic musicianship materialized across multiple instruments, while his partnership with engineering specialists yielded unprecedented sonic possibilities. His television appearances crystallized the image of a former child performer who had matured into an electronic music pioneer, deftly manipulating synthesizers with remarkable precision. The technological advancements of the era aligned perfectly with Wonder’s innovative aspirations, allowing him to construct intricate arrangements that challenged mainstream music conventions. “Living for the City” mainly illuminates the album’s essence, examining systemic racism through personal narratives while demonstrating Wonder’s technical mastery. His minimal recording approach and an unrelenting drive for experimentation distinguished his artistic method from his contemporaries. Innervisions formed Wonder’s creative philosophy, merging universal musical accessibility with pointed social critique about racial inequality and human determination.

1974: Minnie Riperton, Perfect Angel

A chance meeting at a 1971 Chicago gathering sparked an unexpected alliance between Minnie Riperton and Stevie Wonder, culminating in creating Perfect Angel. Their partnership required ingenuity to circumvent record label constraints—forming Scorbu Productions enabled Wonder’s participation under the alias “El Toro Negro.” The musical collaboration merged funk, reggae, folk, and soul elements, highlighting Riperton’s expanding artistic palette. “Reasons” introduced her commanding presence, while “Every Time He Comes Around” revealed sultry undertones. The gentle “Lovin’ You” became her calling card, displaying her five-octave vocal abilities. A reimagined version appears on the deluxe edition, incorporating Brazilian jazz arrangements. Their shared countercultural philosophies and mutual appreciation for music’s transformative qualities cemented a creative bond beyond the recording studio.

1975: Earth, Wind & Fire, That’s the Way of the World

Among 1970s R&B recordings, That’s the Way of the World solidified Earth, Wind & Fire’s artistic apex. While Open Our Eyes achieved gold status with half a million copies sold, its successor multiplied that success tenfold, propelling the group into mainstream consciousness. Maurice White’s production manifested particularly in “Shining Star,” whose infectious groove became the group’s first Billboard Hot 100 chart-topper. The soulful meditation of “Reasons” showcased Philip Bailey’s falsetto mastery, establishing itself as a perennial slow-jam favorite. Beneath radio favorites lay equally magnetic compositions—“Happy Feelin’” burst with celebratory brass arrangements, while “See the Light” married secular and sacred traditions through gospel-influenced harmonies. “Yearnin’ Learnin’” demonstrated the band’s command of syncopated funk, its brass section punctuating each phrase precisely. This sixth studio effort, selling five million copies, outshone its predecessors through consistent musical excellence across every arrangement. Each note on the title track illustrated the ensemble’s refined musicianship, cementing their status as architects of sophisticated soul music.

1976: Stevie Wonder, Songs In the Key of Life

Historical documentation must accurately capture Stevie Wonder’s transformative impact on R&B evolution. His 1971 artistic independence initiated unprecedented musical explorations, culminating in Songs In the Key of Life. The 1976 release followed two years of intensive creative development, yielding an ambitious fusion of musical traditions. Wonder blends funk’s rhythmic drive, jazz’s improvisational spirit, pop’s accessibility, and Latin music’s percussive complexity. These compositions chronicled diverse aspects of Black American life, examining intimate relationships, social justice, and cultural heritage. Released during America’s Bicentennial celebrations, the album presented crucial counternarratives to conventional histories. Its artistic achievements continue inspiring contemporary musicians, while Wonder’s decision to perform it thoroughly almost 50 years later affirmed its lasting relevance.

1977: Bill Withers, Menagerie

Following a phase of creative shifts after his early ‘70s successes, Bill Withers’ album Menagerie marked a rejuvenation in his musical output. Despite not achieving the raw depth of his earlier work, this record spotlights Withers’s ability to write engaging melodies and exceptional vocal proficiency. Menagerie subtly pointed toward the upcoming quiet storm genre by merging his soulful heritage with sleek production. The album’s cohesive sound exudes a laid-back charm, even on the more energetic “Lovely Night for Dancing.” Fans who favored the grittier aspects of his previous hits might find this approach different, but Menagerie undeniably has a welcoming quality that renders it effortlessly enjoyable. With its consistent vibe, soothing feel, and strong songwriting, the album secures its place as a distinguished piece in Withers’ musical history.

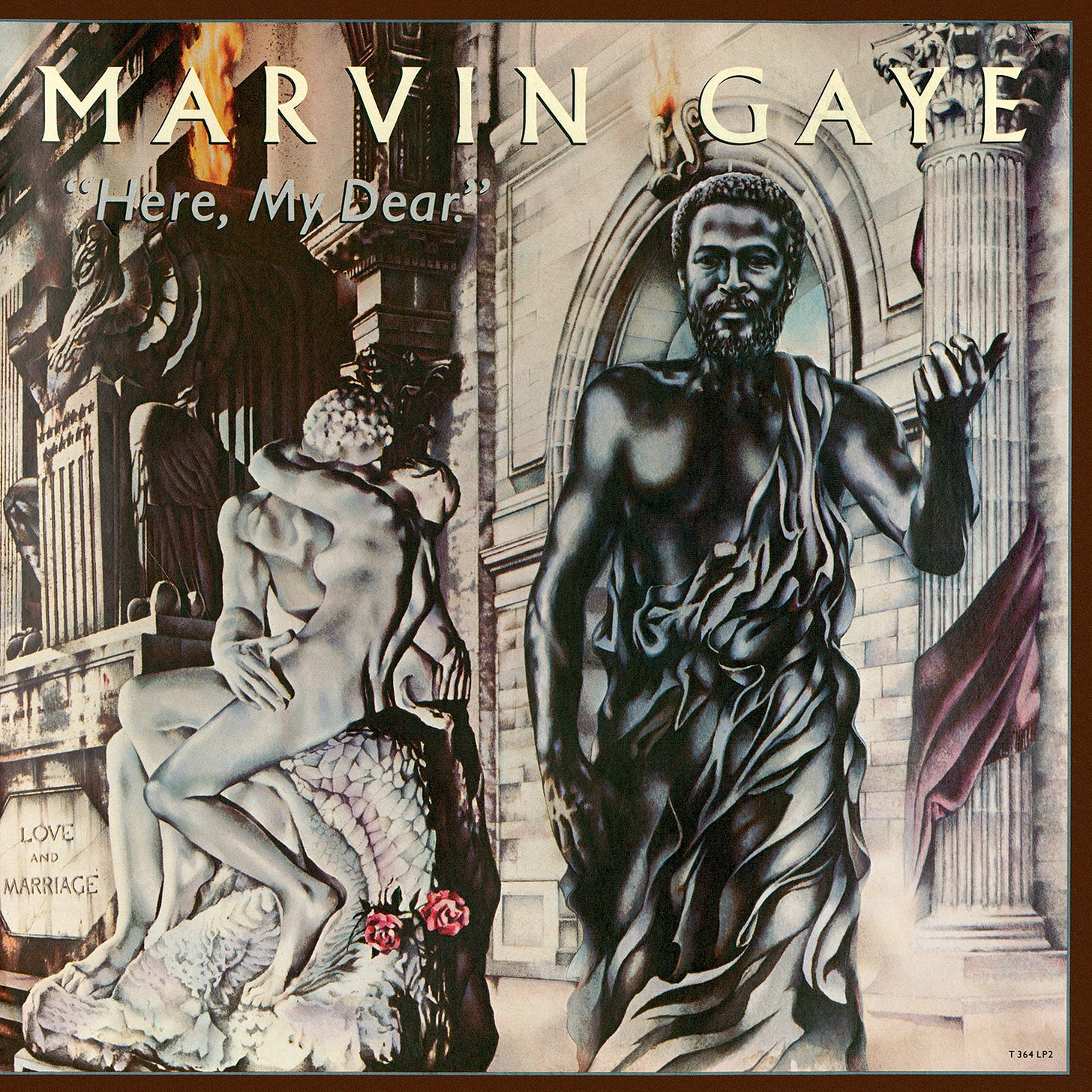

1978: Marvin Gaye, Here, My Dear

Exploring the shift from doo-wop’s simplicity to adult relationship themes, Marvin Gaye’s music mirrored his personal challenges and artistic evolution. Influenced by the pure love songs of the 1950s, his romantic ideals often clashed with the complexities of his marriages and internal struggles. His marriage to Anna Gordy, initially a catalyst for his career, deteriorated due to infidelities and psychological issues. Transitioning from Motown successes to introspective works like What’s Going On, his personal life remained chaotic, including a liaison with teenager Janis Hunter. The dissolution of his marriage to Anna led to Here, My Dear, a groove-rich double album that unraveled the subtleties of their failed relationship. Crafted under legal pressure, this album showcased Gaye’s proficiency in transforming personal anguish into art, blending bitterness with deep introspection. Although it didn’t achieve commercial acclaim, Here, My Dear remains an affecting exploration of love’s intricacies. His later marriage to Hunter was similarly turbulent, emphasizing his ongoing struggle to reconcile his idealized perception of love with reality—a recurring theme in his music.

1979: Michael Jackson, Off the Wall

Transforming the landscape of disco, Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall expanded what the genre could be, transforming the disco landscape. His time at Studio 54 provided inspiration; he observed the club’s energetic environment and audience engagement, letting these experiences ignite his creativity while refraining from its infamous excesses. Partnering with Quincy Jones, he developed a distinctive musical approach that broadened disco’s appeal, merging elaborate orchestration with funk-driven beats. The album begins with “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough,” his first self-composed song, which highlights this fresh direction and became one of four number-one hits from the album. “Working Day and Night” illustrates his tireless commitment, while “She’s Out of My Life” reveals his deep emotional expression. Selling 30 million copies globally, the album’s success reflects its widespread influence. Nonetheless, Off the Wall also exposes contradictions in Jackson’s artistic path—a strict upbringing, a desire for creative liberation, and an ambition for extraordinary commercial success and international fame. This work captures a brief interval where innocence and ambition merged, offering a view into his complex inner world before future challenges clouded his musical legacy.

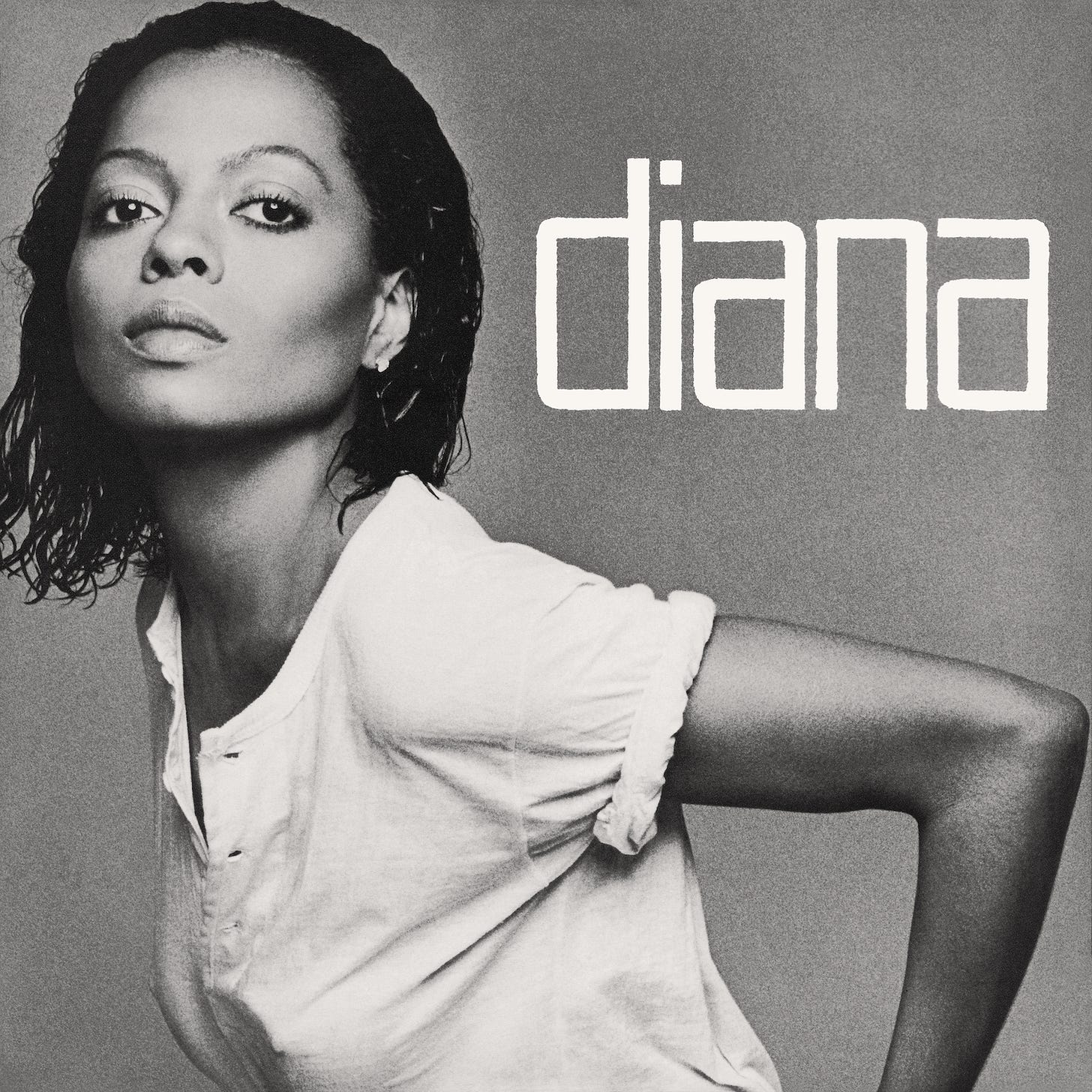

1980: Diana Ross, Diana

Chic basked in disco-funk glory as the 1970s faded, while Diana Ross faced a downturn in her career. Their unlikely collaboration soon produced a pop marvel. Ross sought a fresh start after a series of lukewarm releases and found it with Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards. Their approach to creating Diana involved deep conversations with Ross, transforming her personal stories into catchy melodies. Difficulties arose when Motown, concerned about disco’s decline, demanded changes to Chic’s meticulously crafted mix. Despite this, the album’s 1980 release was a commercial triumph, featuring hits like “Upside Down” and the timeless “I’m Coming Out.” Inspired by Rodgers’ chance encounter with Ross impersonators, the latter song inadvertently cemented her as an LGBTQ+ icon. Diana revitalized Ross’s career and paved the way for pop music in the next decade. Its influence echoes through time, from hip-hop samples to Ross’s ongoing performances of its songs. This union of disco maestros and a Motown legend produced an enduring masterpiece that continues to enthrall fans with its blend of emotion, elegance, and irresistible grooves.

1981: Luther Vandross, Never Too Much

Luther Vandross introduces his solo career with Never Too Much, a collection brimming with R&B excellence. The album underscores his expertise in blending energetic beats with tender ballads, marking the beginning of his journey as a solo artist. Listeners experience a range of tracks, from upbeat, lively songs to those imbued with deep emotion. The lead single climbed to the summit of the Billboard R&B charts, holding the top position for two weeks. Noteworthy tracks like “Don’t You Know That” and “Sugar and Spice” left enduring impressions, while unreleased songs such as “I’ve Been Working” highlight Vandross’s musical adeptness. A highlight is his rendition of “A House Is Not a Home” by Bacharach and David, where he reimagines the classic into a contemporary masterpiece. Though not officially released as a single, this version became a cherished piece in the quiet storm format. The album bridges his former role with the progressive band Change to his solo accomplishments, maintaining the vocal grace and polished sound that had already won over fans before this masterpiece.

1982: Michael Jackson, Thriller

What else to say about this iconic album? Among studio breakthroughs and cultural shifts, Thriller redefined album creation methods. Upon Off the Wall’s foundation, Michael Jackson crafted sophisticated arrangements merging funk, rock, soul, and pop sensibilities. His revolutionary visual presentations on MTV’s platform dismantled racial barriers through magnetic performances. Each composition revealed an artistic range, from “Human Nature’s” quiet contemplation to “Beat It’s” aggressive edge. Beneath the radio-friendly exterior of “Billie Jean” and “Wanna Be Startin’ Something” ran currents of personal unease. This cultural touchstone reshaped entertainment standards, establishing new artistic horizons.

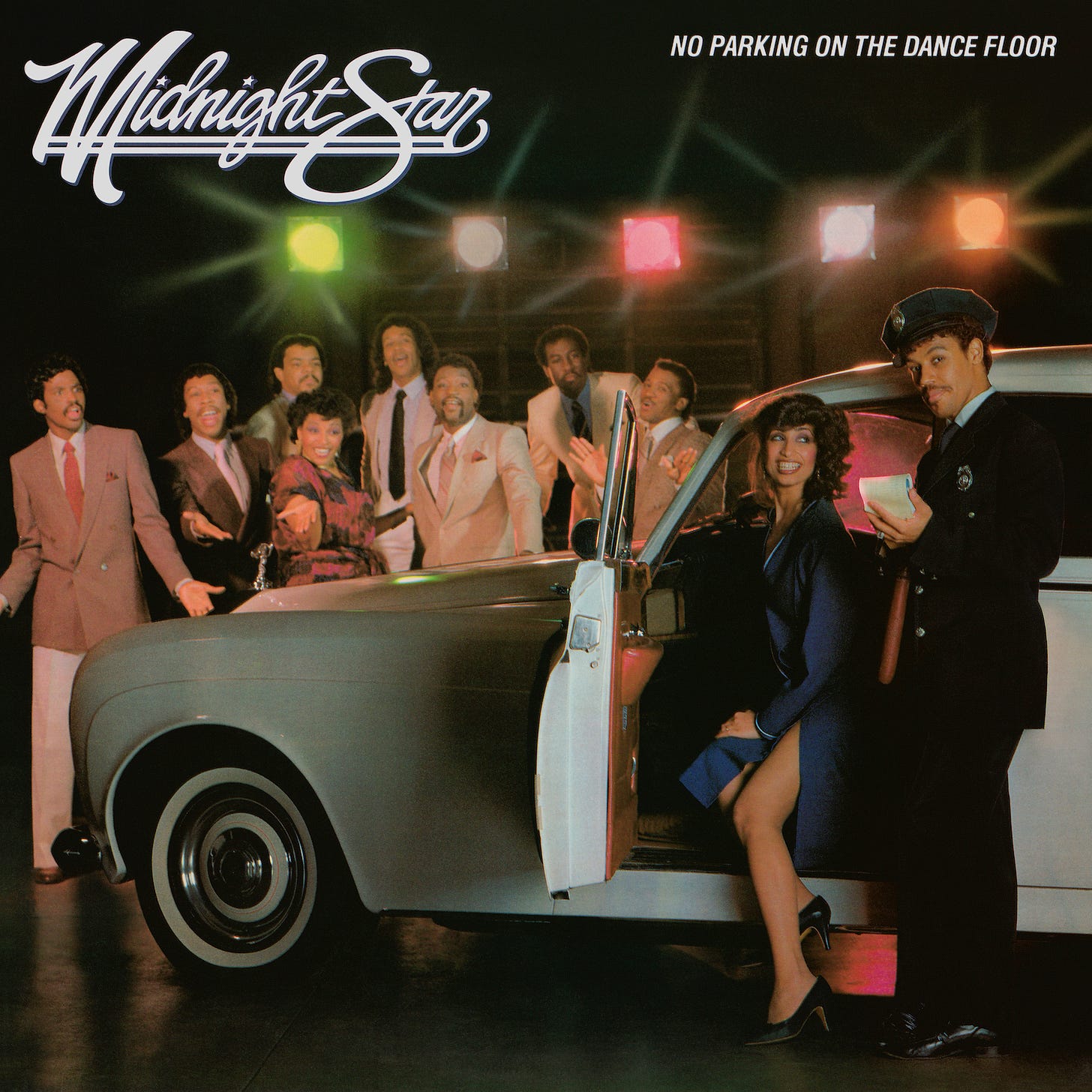

1983: Midnight Star, No Parking On the Dance Floor

Released during R&B’s electronic transformation in 1983, No Parking On the Dance Floor altered commercial dance music’s direction. The Calloways applied their production expertise to mechanized arrangements, as demonstrated in “Freak-A-Zoid’s” machine-driven beats and synchronized vocals. Their command of tempo and arrangement unraveled through “Wet My Whistle,” balancing programmed elements with group harmonies. The title track’s commercial success prompted radio stations nationwide to embrace electronic R&B, while album cuts like “Electricity” highlighted the band’s technical proficiency. Midnight Star’s integration of collective vocals with programmed instrumentation established production techniques that influenced house music’s development. Their calculated approach to arrangement created a dynamic between mechanical precision and vocal warmth that subsequent electronic musicians adopted.

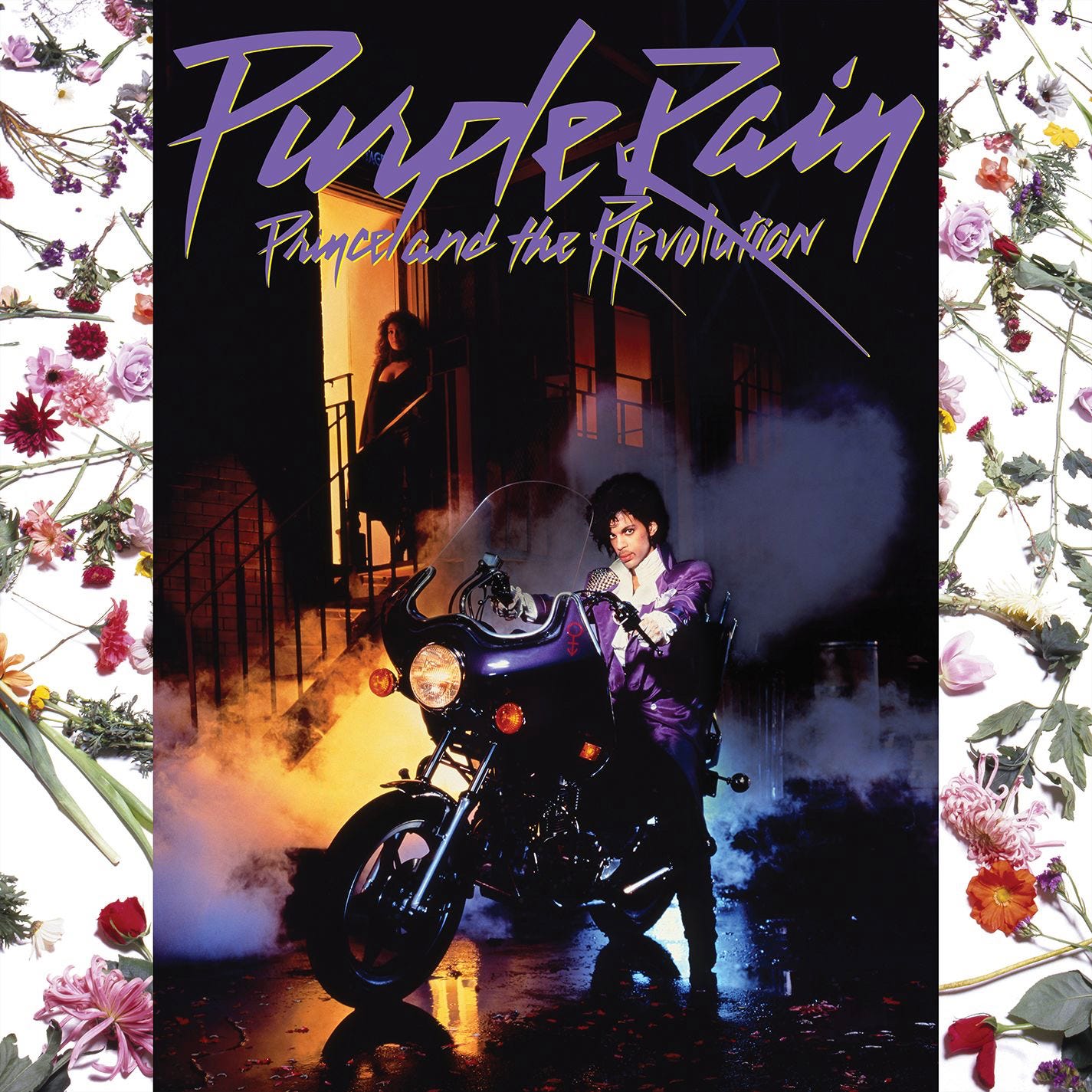

1984: Prince and the Revolution, Purple Rain

The musical revolution of Purple Rain catapulted Prince from Minneapolis clubs to international stardom. His compositional range shines across each track’s distinct character: “Darling Nikki” pulses with primal energy, its calculated rhythms creating an atmosphere of uninhibited passion. “When Doves Cry” achieved Billboard supremacy through its stripped-down arrangement and confessional narrative. The jubilant “I Would Die 4 U” pairs with the confident swagger of “Baby I’m a Star,” highlighting his pop songcraft mastery. The epic title track closes the album with sweeping grandeur, combining evangelistic vocal delivery with guitar virtuosity. This final statement elevates the entire work into transcendent territory. The album crystallized Prince’s reputation as a musical polyglot who could excel across genres while retaining his authentic artistic identity.

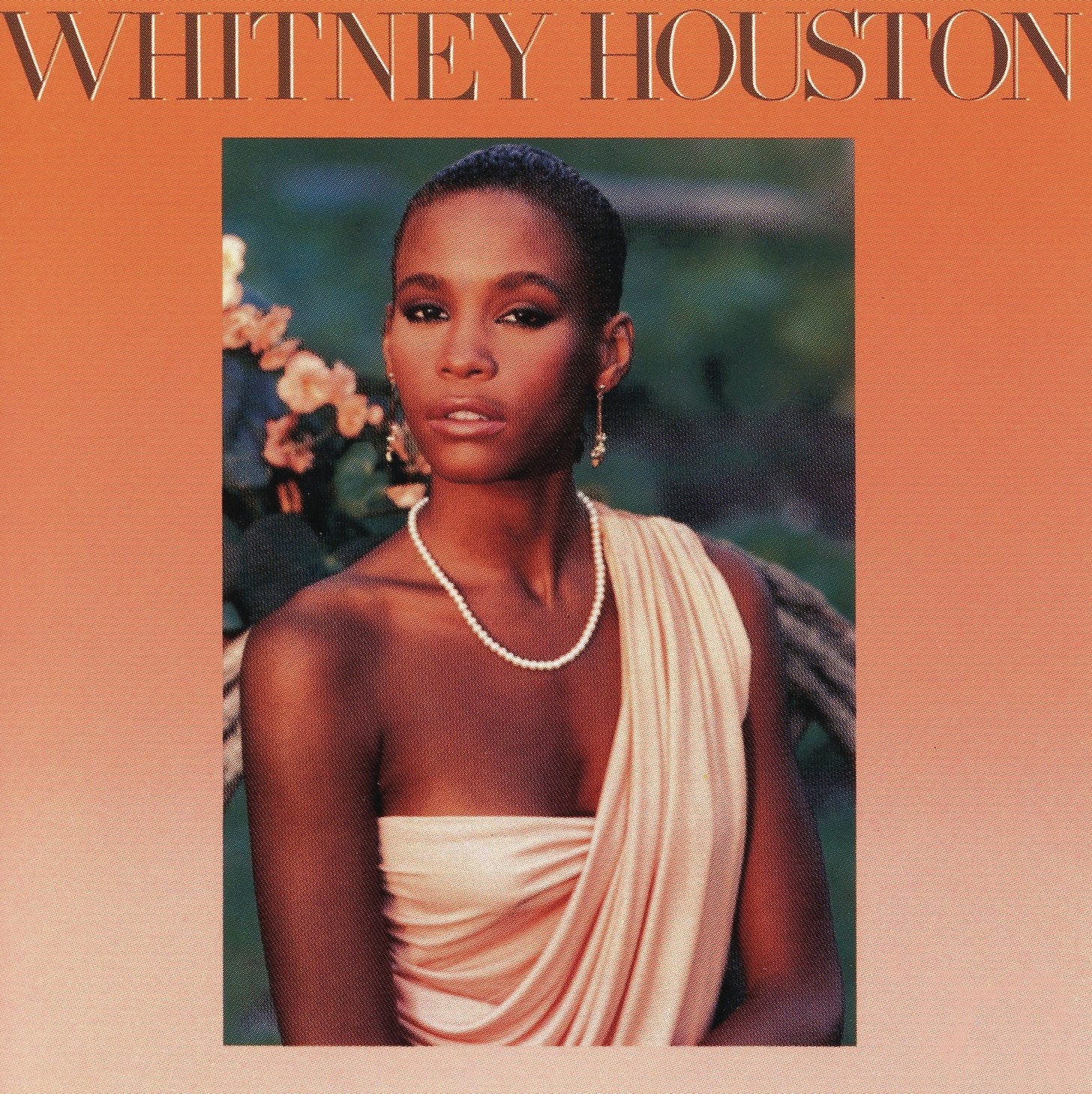

1985: Whitney Houston, Whitney Houston

Under Clive Davis’s astute direction, this collection from Whitney Houston’s classic debut LP married refined R&B sensibilities with majestic vocal arrangements, crafting an innovative hybrid that beckoned to multiple audiences. “Greatest Love of All” anticipated the rise of vocal maximalism, yet the nuanced interpretations in “Saving All My Love for You” and “You Give Good Love” unveiled Houston’s interpretative mastery. The buoyant “How Will I Know” and the often-overlooked “Thinking About You” introduced rhythmic dynamism to her artistic palette. These spirited components, less frequent in subsequent releases, enriched the album’s scope. This inaugural offering crystallized Houston’s artistic essence through ten carefully curated tracks, establishing a blueprint for vocal pop while inspiring generations of performers.

1986: Anita Baker, Rapture

Detroit’s sacred spaces molded Anita Baker into an extraordinary vocalist long before her commercial success materialized. Her early exposure to gospel harmonies merged with an appreciation for jazz virtuosos, particularly Sarah Vaughan’s masterful techniques. The 1980s witnessed Baker’s initial foray with Chapter 8, a disco/funk collective whose brief stint ended after a single recording. This setback led to a temporary withdrawal from music, during which she sustained herself through service industry roles. Her subsequent alliance with Elektra Records granted unprecedented artistic autonomy, culminating in Rapture. As executive producer, Baker orchestrated a revolutionary fusion of R&B and jazz sensibilities. “Sweet Love” introduces Baker’s astonishingly mature contralto, displaying wisdom beyond her twenty-seven years. Each arrangement on Rapture unfolds like an intricate musical dialogue, where instruments and vocals engage in seamless conversation. “Caught Up In the Rapture” shows this artistry, as Baker transmutes conventional lyrics into pure emotional expression, then expertly reconstructs them into coherent narratives.

1987: Prince, Sign O’ the Times

Prince’s musical genius crystallizes throughout Sign O’ the Times, where sacred hymns meet street corner serenades. The compositions twist through funk’s swagger, rock’s muscle, and soul’s heart, creating his alchemical brew. His vocals sweep from velvet whispers to passionate proclamations; each note precisely placed yet seemingly spontaneous. Musical structures refuse to stay still - songs evolve mid-flight, keeping minds and bodies guessing. “The Cross” ascends from spare beginnings to orchestral heights, while “Play in the Sunshine” pirouettes through unexpected sound doorways. Prince peoples his musical world with distinctive characters, from “Starfish & Coffee”’s dreamlike figures to “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker” vivid portraits.

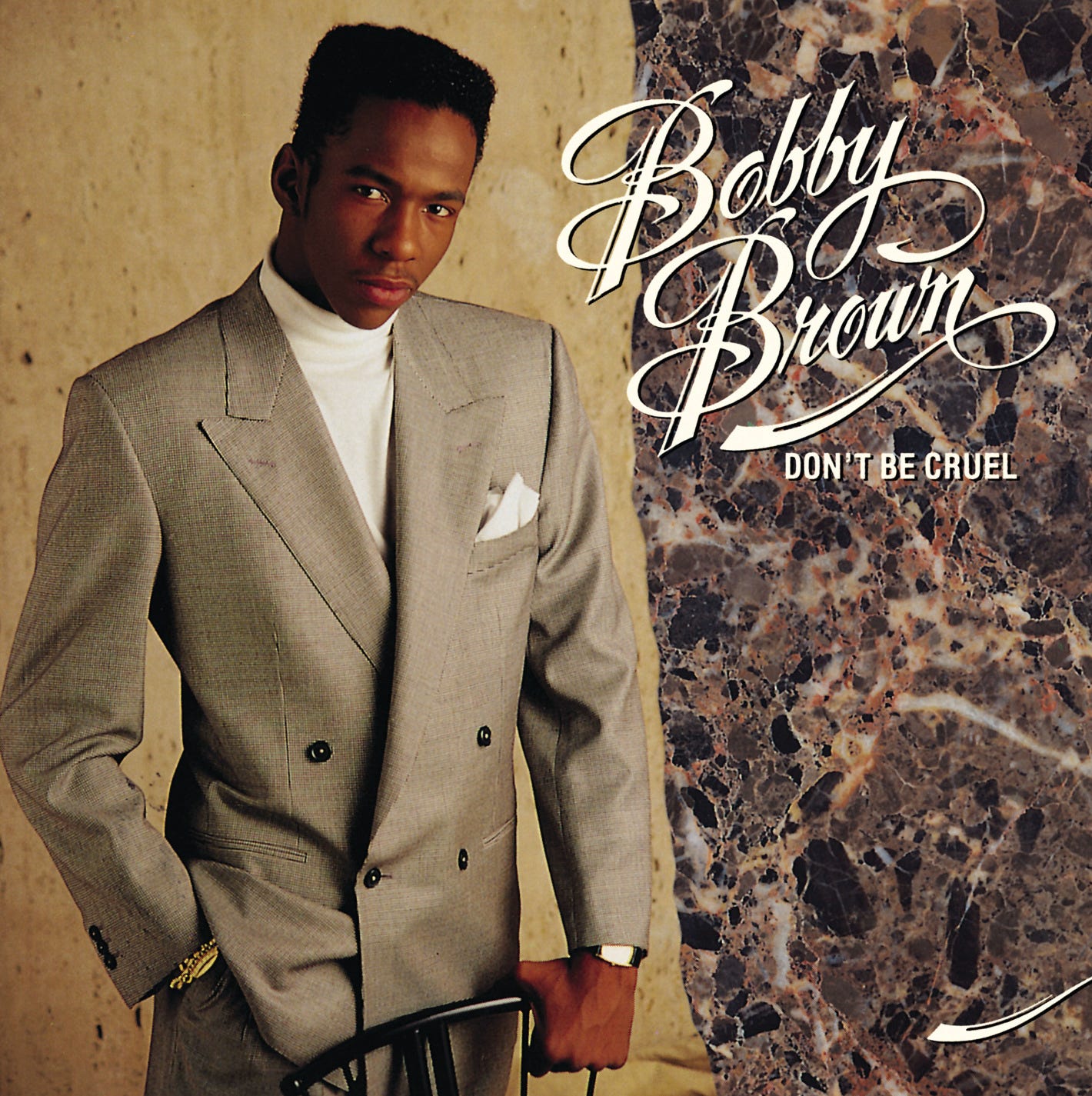

1988: Bobby Brown, Don’t Be Cruel

Bobby Brown’s artistic reinvention through Don’t Be Cruel paralleled Janet Jackson’s transformative Control, shattering his previous musical constraints. The album’s revolutionary approach merged traditional soul vocals with hip-hop elements, establishing Brown as the New Jack Swing’s architectural innovator. “My Prerogative” and the title track crystallized this musical chemistry, while “Every Little Step,” “Roni,” and “Rock Wit’cha” highlighted his genre-spanning capabilities. Brown’s rap aspirations, cultivated since his New Edition period, reached full fruition here, harmoniously coexisting with his R&B roots. L.A. Reid and Babyface surpassed production expectations, crafting distinctive soundscapes that elevated their typical methodology. This artistic collaboration propelled Brown into uncharted territory, solidifying Don’t Be Cruel as a force in the late ‘80s musical innovation.

1989: Janet Jackson, Rhythm Nation 1814

The twilight of the 1980s witnessed America at an inflection point. George H.W. Bush succeeded Reagan’s administration amid mounting social turmoil—gun violence surged, crack cocaine ravaged communities, AIDS activists challenged institutional apathy, and hip-hop artists raised their voices against street violence. Janet Jackson recorded an unexpected revolutionary with Rhythm Nation 1814, transforming the zeitgeist into musical innovation. Her artistic metamorphosis manifested through a masterful fusion of social awareness and pop sensibility, while the round-the-clock news cycle shaped her creative vision. The partnership between Jackson and production virtuosos Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis birthed an unprecedented soundscape. Metal-tinged guitar work intertwined with synth-funk foundations, creating multilayered compositions that challenged contemporary pop conventions. Jackson’s vocal performance shattered preconceptions, revealing a commanding range beyond her whispered tones.

1990: Tony! Toni! Toné!, The Revival

Tony! Toni! Toné! established themselves in R&B by uniting contemporary urban sounds with a deep-seated admiration for ‘70s soul and funk. Their second album, The Revival, showcases this musical synthesis, combining advanced technology with an authentic, soulful foundation. Tracks such as “The Blues,” “Oakland Stroke,” “Let’s Have a Good Time,” and the chart-topping “Feels Good” display the group’s expertise in crafting gritty, technology-infused funk while skillfully navigating their sonic palette. Drawing inspiration from various artists—including Digital Underground, Sly & the Family Stone, Parliament/Funkadelic, and Prince—they demonstrated adaptability with smooth slow jams like “I Care” and the well-loved “It Never Rains in Southern California.” Many urban contemporary records lacked depth, so The Revival stood apart by seamlessly blending artistic vision with mainstream appeal, affirming its importance in the R&B genre.

1991: Jodeci, Forever My Lady

Jodeci formed from the alliance of two sets of brothers. The DeGrate siblings, Dalvin and Devante Swing joined forces with JoJo and K-Ci Hailey to produce a sound-balancing nostalgic soul with innovative production techniques. Their first album, Forever My Lady, showcased this distinct combination, uniting traditional vocal prowess with the boldness of hip-hop production. While hip-hop-influenced tracks were present, the sincere ballads greatly impacted the most. “Come and Talk to Me” and the title track quickly became beloved favorites, resonating strongly with urban contemporary audiences. These emotive love songs thrust Jodeci into the limelight and hinted at a broader change in musical preferences. The strong response to these tracks pointed to a gradual movement away from the New Jack Swing sound, indicating a transformation in the music industry on the horizon.

1992: Mary J. Blige, What’s the 411?

Launching her career with What’s the 411?, Mary J. Blige changed the music industry by fusing hip-hop with soul. Her vocals throughout the album are powerful, displaying both skill and deep emotion. Tracks like “Real Love” and “Sweet Thing” demonstrate her ability to create soul classics that stand the test of time. Meanwhile, “You Remind Me” and her collaboration with K-Ci from Jodeci highlight her versatility. The production, featuring work from Diddler and others, blends a streetwise vibe with soulful tunes. Some synthesizer-focused backgrounds seem outdated compared to Blige’s ageless performances. The album is rich in hip-hop influences, including Blige’s rap on the title track, though she explored different directions in later albums. While certain production elements and concepts like answering machine skits feel antiquated now, the album’s essence stays solid and influential. Blige’s sincere voice and the album’s original mix of genres secured its place as a trailblazing work in R&B and hip-hop.

1993: Toni Braxton, Toni Braxton

Few debuts announce themselves with the quiet authority of Toni Braxton. Her 1993 arrival brought a distinctive voice to R&B, a smoky contralto that could convey volumes through subtle shifts in tone and texture. Rather than surrendering to unrestrained emotion, Braxton’s interpretations gain power through their poised restraint. Babyface and L.A. Reid’s production team are ideal collaborators, creating varied musical settings that showcase their singer’s range while maintaining artistic coherence. Their sophisticated arrangements provide the perfect canvas for Braxton’s artistry, resulting in songs that resonate regardless of listener demographics. This partnership established a new benchmark for emotionally intelligent R&B.

1994: Mary J. Blige, My Life

On My Life, Mary J. Blige’s brass-inflected mezzo-soprano cuts through conventional R&B parameters, establishing an unmistakable artistic identity. Her vocal approach shares more lineage with Annie Lennox than soul traditionalists, displaying remarkable control in note manipulation. Chucky Thompson and Trackmasters construct subtle sonic landscapes that amplify rather than compete with Blige’s commanding presence. Guest appearances, while reflecting hip-hop’s collaborative ethos, occasionally expose songwriting limitations. These supposed flaws, however, contribute to the album’s genuine appeal. “Be Happy” closes the collection by transmuting personal struggles into an anthem of perseverance. This artistic breakthrough preceded collaborations yielding hits with “Not Gon’ Cry” and “Family Affair.” Later works, Mary and No More Drama, expanded upon these creative cornerstones, documenting her evolution through adversity and triumph. Her innovative fusion of classic soul elements with contemporary R&B sensibilities established an influential framework.

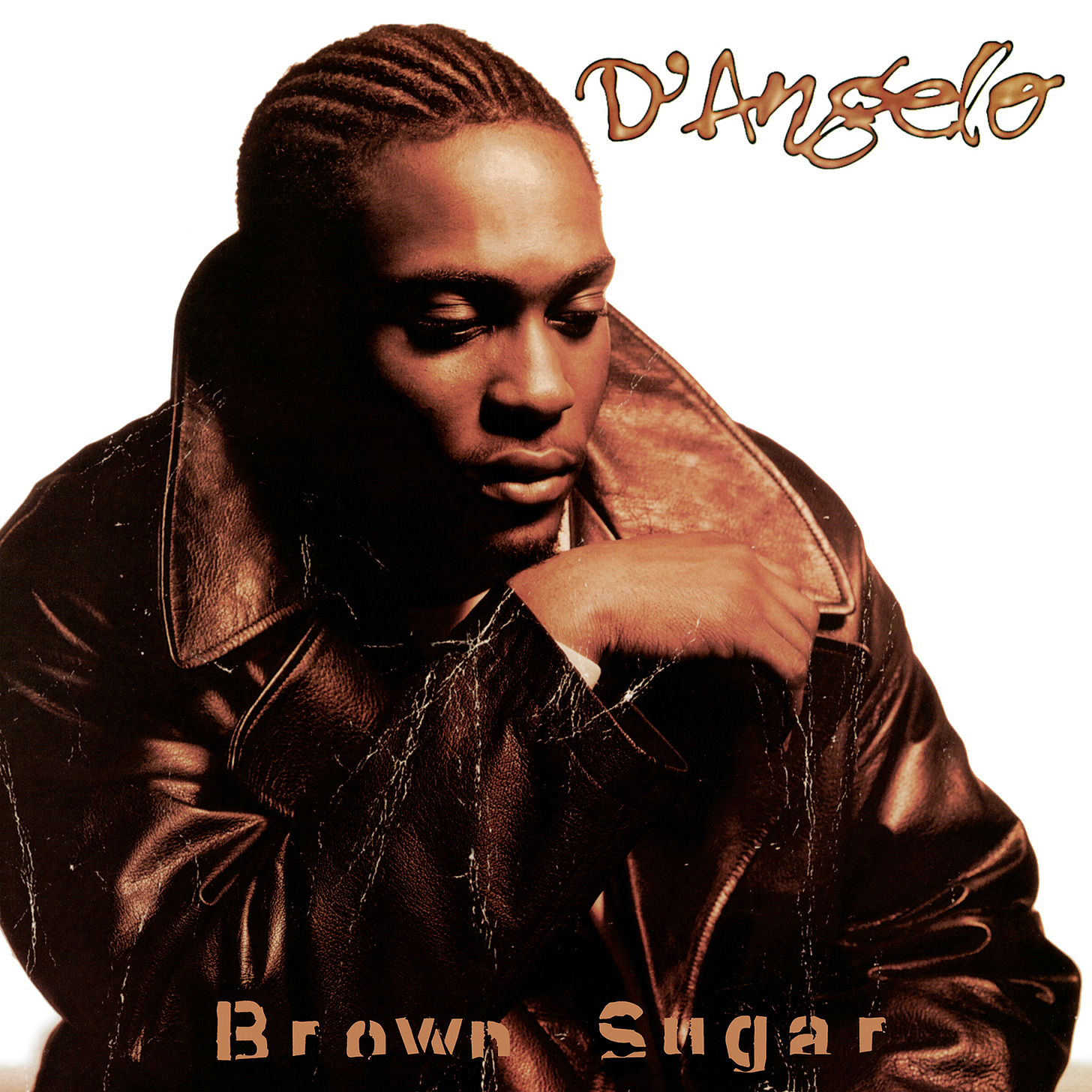

1995: D’Angelo, Brown Sugar

At just 21, the Richmond-born D’Angelo crafted an album that married classic soul’s warmth with hip-hop’s rebellious spirit. The mid-90s R&B landscape changed forever when he released Brown Sugar. While his peers recycled samples and drum loops, D’Angelo channeled the ghosts of soul music through live instrumentation and raw conviction. His instincts sparked magic on “Brown Sugar,” where honeyed vocals float over hypnotic Rhodes piano, creating an intoxicating ode to cannabis culture. His rendition of “Cruisin’” transforms Smokey Robinson’s sweet romance into a smoldering late-night confession, while “Shit, Damn, Motherfucker” burns with the intensity of gutbucket blues filtered through modern-day heartache.

1996: Maxwell, Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite

Brooklyn-bred Maxwell painted romance through velvet-smooth vocals and meticulous arrangements, crafting an aural chronicle of love’s progression—from chance meetings to matrimonial ecstasy. His Caribbean heritage melded with jazz inflections and funk grooves, while partnerships with Stuart Matthewman and Leon Ware yielded studio magic without compromising his artistic vision. The album’s sophisticated portrayal of Black romance and spiritual connection carved a distinct path away from mid-90s street narratives. His bohemian philosophy and contemplative songwriting presented an alternative to gangsta rap’s bravado, drawing audiences toward more intimate musical expressions. Though sales initially crawled, persistent radio exposure and visual promotion propelled the record to platinum heights and Grammy recognition. Alongside D’Angelo and Erykah Badu’s contributions, Urban Hang Suite helped architect neo-soul’s foundation, revolutionizing late 90s R&B. Maxwell’s treatment of passion and sensuality eschewed explicit territory for deeper emotional resonance, prioritizing spiritual bonds over physical display. His artistic choices—blending live instrumentation with studio precision—paid homage to 70s soul while pioneering new territories.

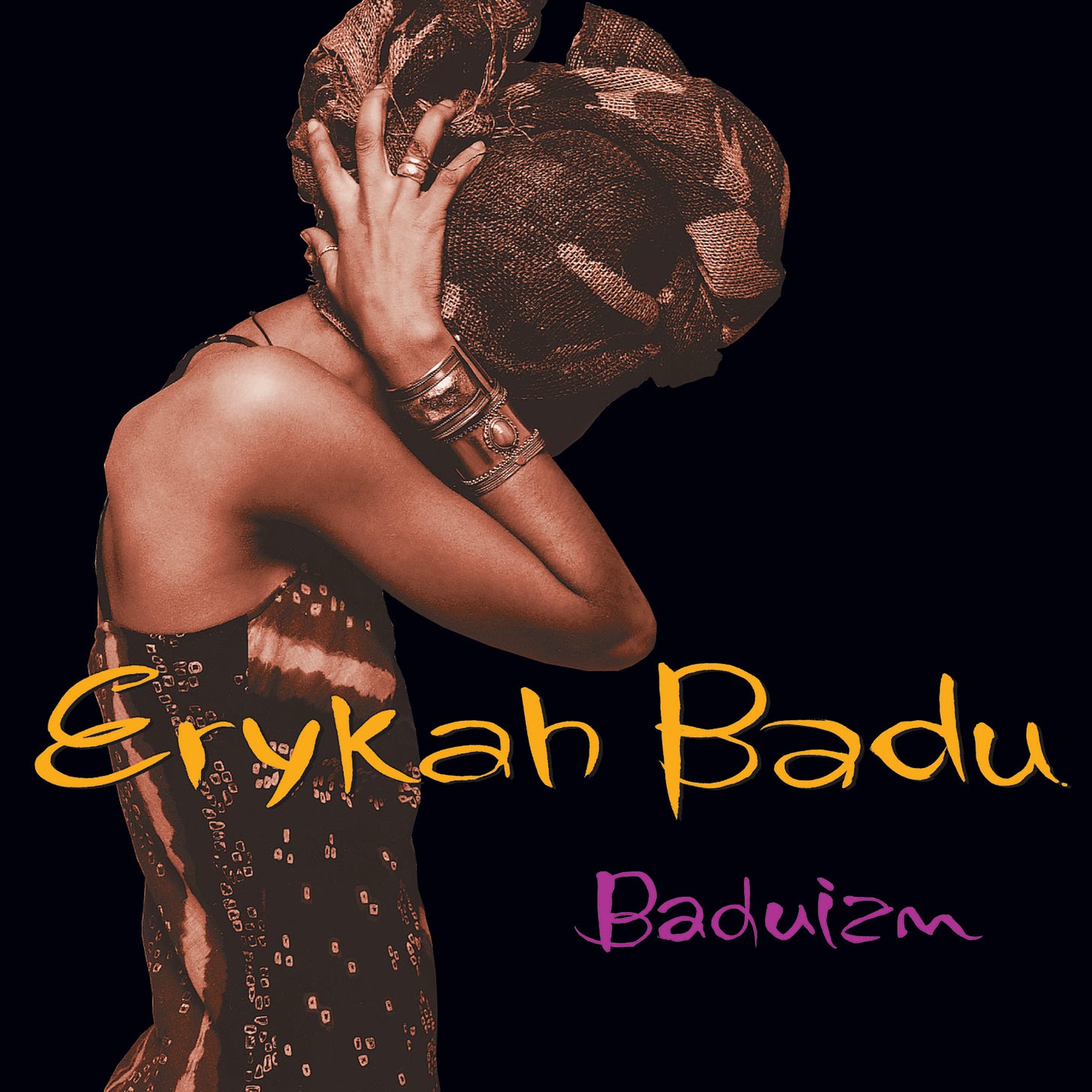

1997: Erykah Badu, Baduizm

When Baduizm dropped, R&B already pulsated with luminaries like Aaliyah, Mary J. Blige, and Usher ruling radio waves. Erykah Badu carved her niche, melding jazz improvisations with blues undertones and hip-hop’s rhythmic backbone. Her distinctive voice—a mix of hoarse whispers and playful cackles—echoed Billie Holiday’s spirit while speaking to modern sensibilities about self-discovery, love’s complexities, and spiritual awakening. Universal executive Kedar Massenburg coined “neo-soul” to package this renaissance of live instrumentation and vocal authenticity, though artists often rejected such pigeonholing. Yet Baduizm soared beyond marketing schemes, earning double platinum certification and a Grammy for Best R&B Album. The record’s philosophical heart beat strongest in “On and On,” “Next Lifetime,” and “Otherside of the Game,” where Badu’s lyrical wisdom met her singular vocal approach. Drawing from 1980s harmony groups and early Meshell Ndegeocello’s innovations, Badu pushed further into unexplored creative territories. The bookending “Rim Shot” versions revealed her fascination with music’s building blocks, while partnerships with The Roots added instrumental richness. African aesthetics, numerology, and social consciousness threaded throughout, establishing patterns defining her artistic evolution.

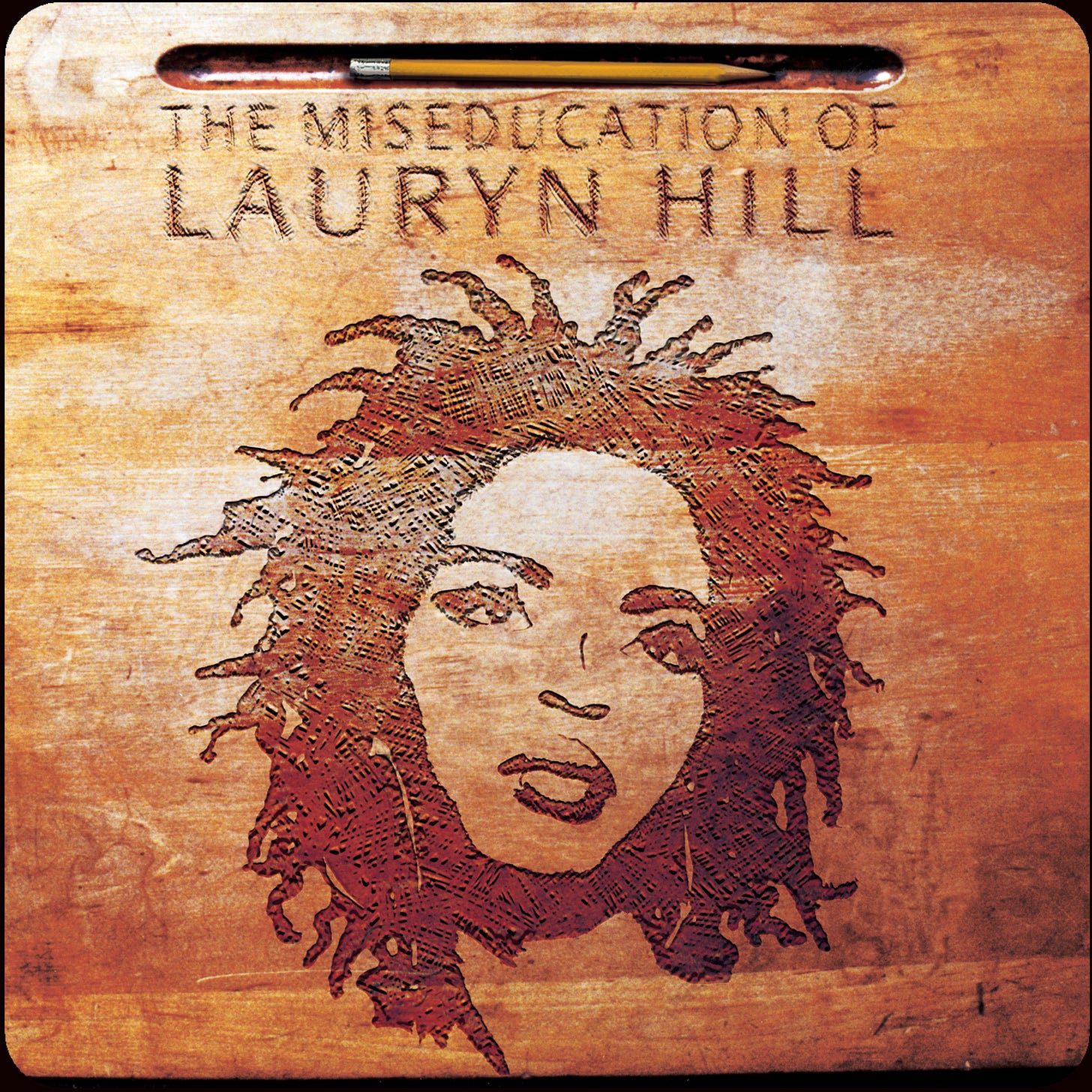

1998: Ms. Lauryn Hill, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill burns with unfiltered truth and artistic independence. Ms. Hill orchestrated a masterful blend of hip-hop’s raw energy, Motown soul’s warmth, and reggae’s spiritual pulse. The mystical atmosphere of Bob Marley’s Tuff Gong Studios, where portions were captured, reflects her journey through motherhood and artistic awakening. Her verbal mastery ignites “Lost Ones” and “Doo Wop (That Thing),” while “Ex-Factor” and “To Zion” reveal soul-baring vulnerability. Personal truth illuminates every moment - from love’s battlegrounds to motherhood’s sacred spaces, identity’s maze to faith’s foundation. Eschewing ‘90s hip-hop conventions, she drew deeply from Black music’s rich heritage. Her bold exploration of womanhood, racial identity, and spirituality carved new paths for authenticity in rap and neo-soul.

1999: Meshell Ndegeocello, Bitter

Meshell Ndegeocello questions rigid gender roles and sexual identity throughout Bitter, creating music where opposing energies merge and split apart. The album’s skeletal arrangements evoke empty rooms and aged wood while preserving soul music’s emotional essence in more subdued forms. Her atmospheric reimagining of Hendrix’s “May This Be Love” captures the record’s themes of duality and connection, allowing her to morph between different aspects of identity within its dreamy soundscape. Though crowned Newsweek’s album of the year, Bitter’s artistic evolution away from radio-friendly territory affected its commercial impact. This stripped-down approach illuminates her musical alchemy, mixing genres while mining emotional depths.

2000: D’Angelo, Voodoo

D’Angelo conjured Voodoo at the millennium’s edge, a sonic spell cast just as digital waves began eroding CD culture’s shores. While mainstream offerings fought for attention, this meticulously crafted opus climbed charts through pure artistic merit. Huddled among vintage gear, D’Angelo and his musical family channeled soul’s golden age, their dedication bleeding into every recorded moment. The album painted vast canvases of spirituality and feminine power, while D’Angelo’s virtuosic performance honored his musical ancestors. The impact of “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” altered trajectories unexpectedly. Its intimate visuals thrust D’Angelo into overwhelming scrutiny, triggering a disappearing act marked by inner turmoil. Critics and devotees watched the horizon for signs of return (spoiler: he returned in 2014), their anticipation growing with each passing season. Yet Voodoo endures its influence multiplying as new generations stumble upon its hypnotic charms, each spin revealing fresh nuances in its design.

2001: Aaliyah, Aaliyah

Aaliyah crafted an alchemical fusion of avant-garde impulses and soul traditions on her final studio album. Her bright, wispy soprano acquired newfound bite, while multi-layered harmonies painted intricate textures across the record. The Supafriends and Blackground producers constructed sonic architectures that vary between triple-time futurity and vintage R&B warmth. Static Major’s songwriting partnership helped shape an aesthetic that challenged pop conventions while maintaining dialogue with mainstream sounds. “We Need a Resolution” and “More Than a Woman” exemplified her gift for selecting material that showcased her interpretative abilities, while deeper album cuts revealed meditations on inner strength and self-knowledge. By bridging pop, R&B, and hip-hop sensibilities, she anticipated stylistic shifts that would ripple through music for years to come. Beyond the music, Aaliyah’s revolutionary approach to fashion and movement makes casual wear feel opulent and embraces fluid choreography.

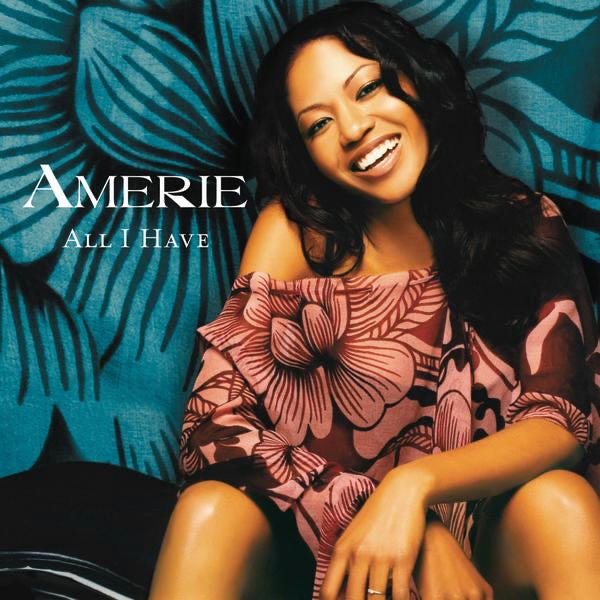

2002: Amerie, All I Have

A chance encounter at McDonald’s sparked magic when Amerie crossed paths with producer Rich Harrison in a parking lot, birthing one of the most distinctive R&B collaborations. Their creative chemistry materialized as All I Have, a twelve-track collection where silky vocals intertwined with Harrison’s signature percussion. The Korean and African-American singer’s honeyed melodies floated atop muscular beats, creating an alluring contrast that appealed across gender lines. While established stars dominated that year’s R&B landscape, Amerie carved her own lane through sheer artistic determination. Though the album scaled Billboard’s top 10, its richness ripened slowly, like wine aging to perfection. Her story illuminates how success often follows its timeline, rewarding those who remain steadfast in their artistic vision.

2003: Meshell Ndegeocello, Comfort Woman

The sultry depths of Comfort Woman reveal Meshell Ndegeocello’s genius for musical alchemy. Bass lines throb like midnight heartbeats beneath arrangements that marry dub reggae’s spaciousness to the soul’s emotional truth and jazz’s spontaneous spirit. Her voice shifts from a velvet whisper to a passionate cry, leading listeners through an intimate sonic dreamscape. The smoldering intensity of “Love Song” contrasts with “Come Smoke My Herb’s” psychedelic haze, showcasing her range. Guitar virtuosos Oren Bloedow and Doyle Bramhall add shimmering textures, and their contributions are perfectly balanced in the crystalline mix. Each musical element occupies its own space while contributing to the whole’s hypnotic power. Ndegeocello’s revolutionary approach shatters preconceptions about soul music’s boundaries, suggesting thrilling new directions. Her technical mastery serves raw emotional expression, creating music that resonates in body and mind. Comfort Woman captures an artist operating at maximum creative voltage.

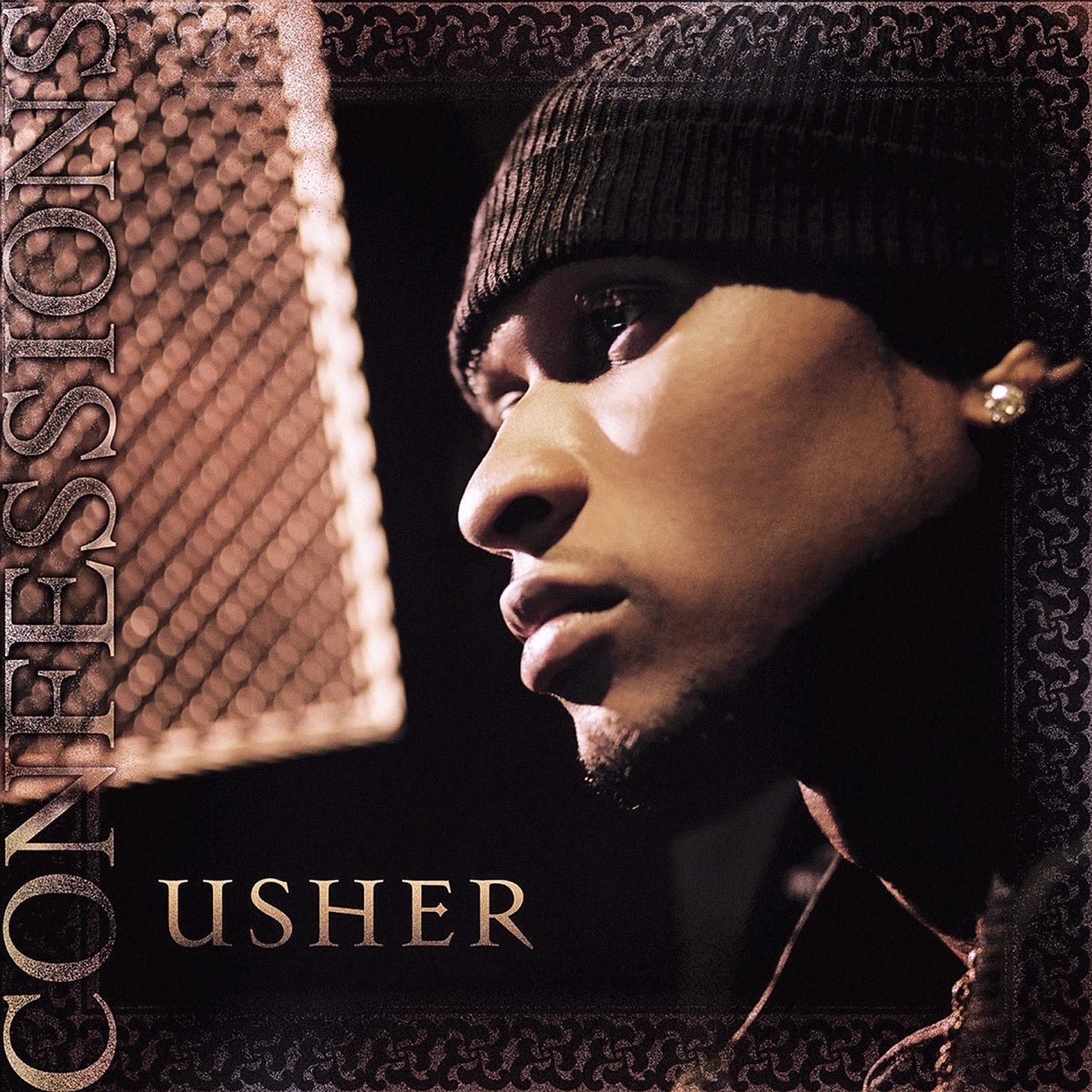

2004: Usher, Confessions

Through the prism of guilt and redemption, Confessions details an intimate chronicle of romantic missteps and emotional reckonings. Across 60-plus minutes, Usher’s singing virtuosity radiates through moonlit soul arrangements and slow jams that mirror bodies sliding across satin sheets. A murderers’ row of producers—Jermaine Dupri, Bryan-Michael Cox, Just Blaze, Jimmy Jam, and Terry Lewis—helped architect this confessional suite, drawing inspiration from soul titans like Stevie Wonder, Sam Cooke, and Marvin Gaye. “Confessions Pt. II” anchors the narrative, laying bare the crushing weight of infidelity. When Usher’s label pushed for a club track, “Yeah!” leaked despite his hesitation. The gamble paid off spectacularly—the song ruled the charts for 12 straight weeks. Yet the album’s emotional center crystallizes in “Burn,” where Usher plumbs heartache’s depths with raw vulnerability. His voice maps the territory between desire and despair, each note carrying the ache of lessons learned too late. Confessions revolutionized his artistic path, transforming personal tribulations into universal truth—the kind that makes strangers feel like confidants in the dark.

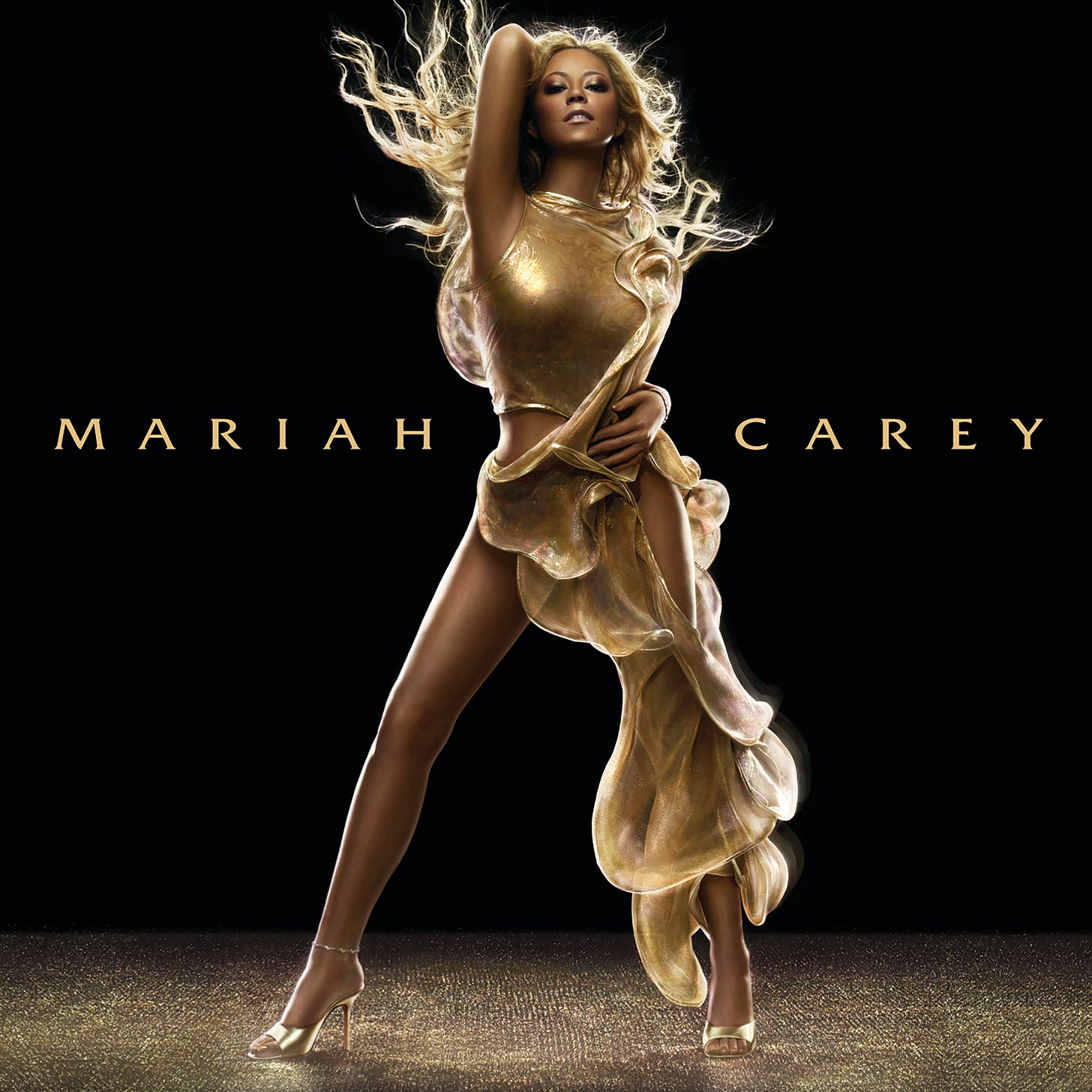

2005: Mariah Carey, The Emancipation of Mimi

Mariah Carey rewrote her narrative through The Emancipation of Mimi. The aftermath of Glitter and industry skepticism had threatened to define her story, but she transformed these obstacles into fuel for innovation. Venturing into Atlanta’s hip-hop territory, she found kinship with producers like Jermaine Dupri, crafting a sound that married R&B’s sensuality with hip-hop’s rhythmic pulse. Her vocal approach on “It’s Like That” and “We Belong Together” revealed newfound subtlety, trading power notes for intimate whispers that captured listeners’ hearts. Mimi became more than a commercial triumph, though chart dominance and multi-million sales followed. The album crystallized Carey’s liberation, celebrating resilience while embracing pure joy. Her artistic metamorphosis drew new devotees to her music while reinforcing her connection with existing fans. This creative rebirth illustrated how artists could honor their roots while pushing toward new horizons.

2006: Beyoncé, B’Day

The anticipation surrounding B’Day, Beyoncé’s second solo outing, sparked intense public discourse. Though “Deja Vu” never matched the explosive success of “Crazy in Love,” its late-‘70s funk undertones ignited dancefloors worldwide. The gritty, confrontational “Ring the Alarm” stirred speculation about hidden meanings, while critics fixated on the album’s provocative title and rushed two-week creation. Against predictions of career suicide, B’Day materialized as an economical yet explosive collection, matching her debut’s magnetism. Rich Harrison’s swagger-filled productions complemented The Neptunes’ nimble arrangements, painting a kaleidoscopic patchwork of sounds. “Freakum Dress” and “Suga Mama” highlighted her verbal acrobatics and authoritative presence, as “Green Light” and “Kitty Kat” illustrated her adaptability across various musical territories. “Upgrade U” solidified into an empowerment anthem, striking an expert balance between dominance and mutual elevation. Beyond the media spectacle, B’Day embodied Beyoncé’s artistic evolution and steadfast self-assurance, shattering any notion of a sophomore slump.

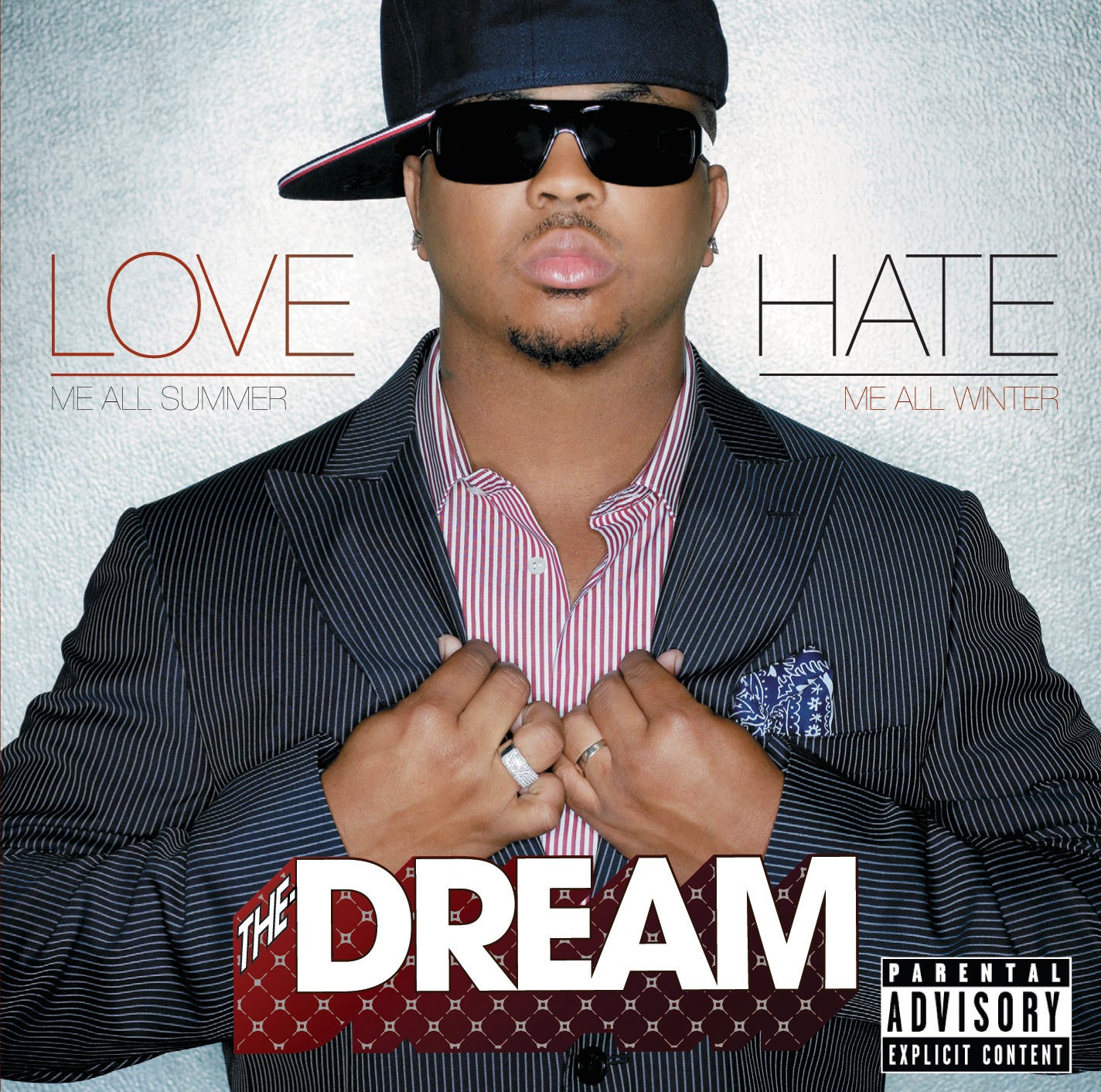

2007: The-Dream, Love/Hate

Before becoming The-Dream, young Terius Nash absorbed the musical education of his mother’s record collection until her untimely death altered his creative trajectory. His partnership with Christopher “Tricky” Stewart sparked a metamorphosis in his artistry, culminating in the 2007 release Love/Hate. The record’s DNA splices Atlanta rap swagger with classic R&B warmth, yielding earworms that burrow deep into consciousness. Nash’s childhood immersion in feminine perspectives uniquely colors his pen game, enabling him to craft anthems like “Umbrella” that resonate across gender lines. His meta-commentary on songwriting mechanics throughout Love/Hate reveals an architect deconstructing his own blueprint.

2008: The Foreign Exchange, Leave It All Behind

On Leave It All Behind, The Foreign Exchange abandons hip-hop’s familiar territory for sultry R&B textures. Phonte trades sharp-tongued verses for honeyed melodies, revealing an unexpected metamorphosis from skilled MC to accomplished vocalist. Nicolay’s production unfolds like twilight settling over a quiet city; warm Rhodes keyboards shimmer beneath gauzy synthesizers while programmed drums whisper rather than bang. Their chemistry yields something rare: electronic soul music that feels intimate and vast.

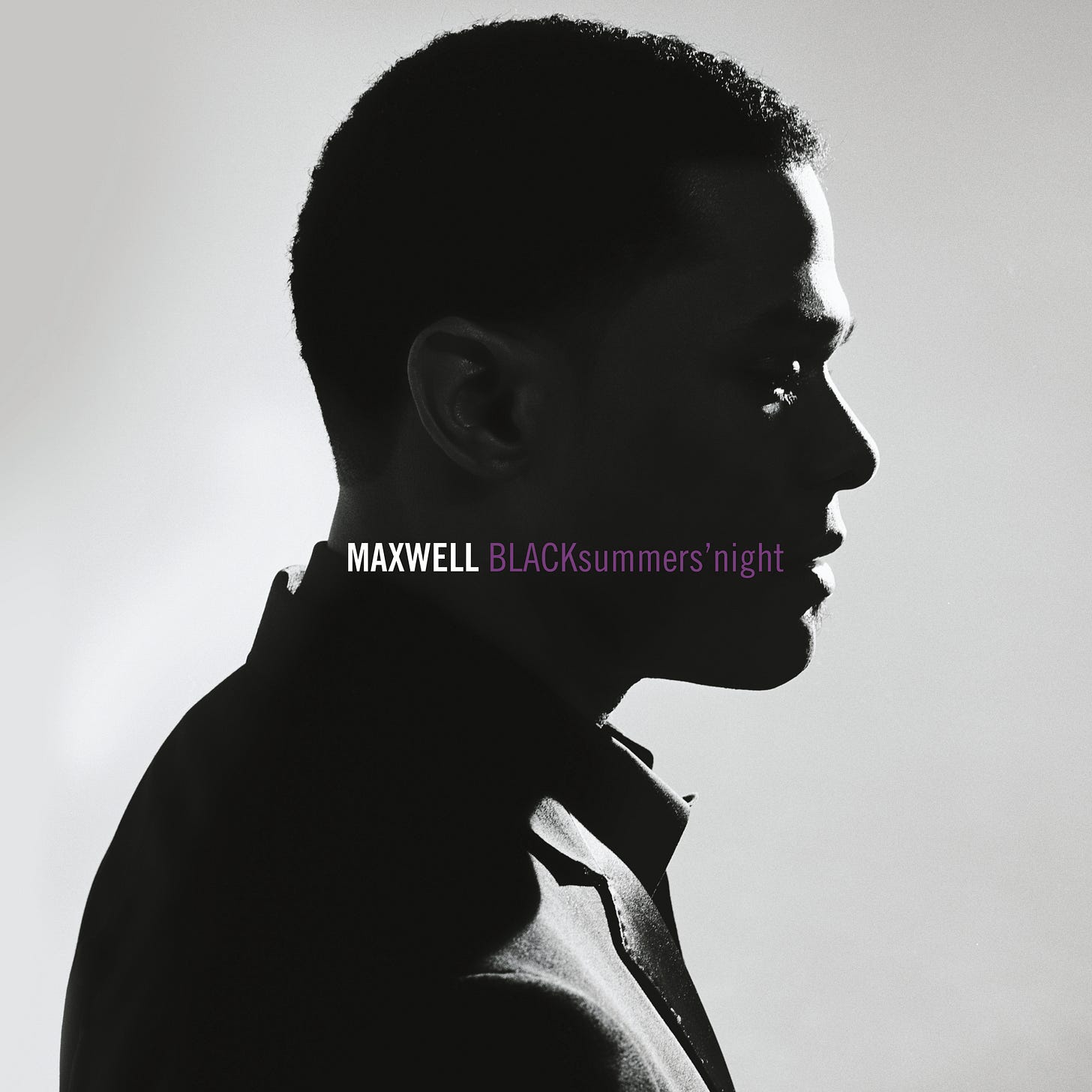

2009: Maxwell, BLACKsummers’night

The musical construction of Maxwell’s BLACKsummers’night shifts away from physical seduction toward technical sophistication. Each arrangement demonstrates careful development through the precise placement of musical elements. “Fistful of Tears” adopts Prince’s musical language via its quarter-note harmony waltz, while “Help Somebody” sustains measured tension. Though “Stop the World” lacks structural stability, its direct approach contrasts the collection. While differing from the cultural significance of Urban Hang Suite, these compositions illustrate Maxwell’s advanced understanding of harmonic and melodic manipulation.

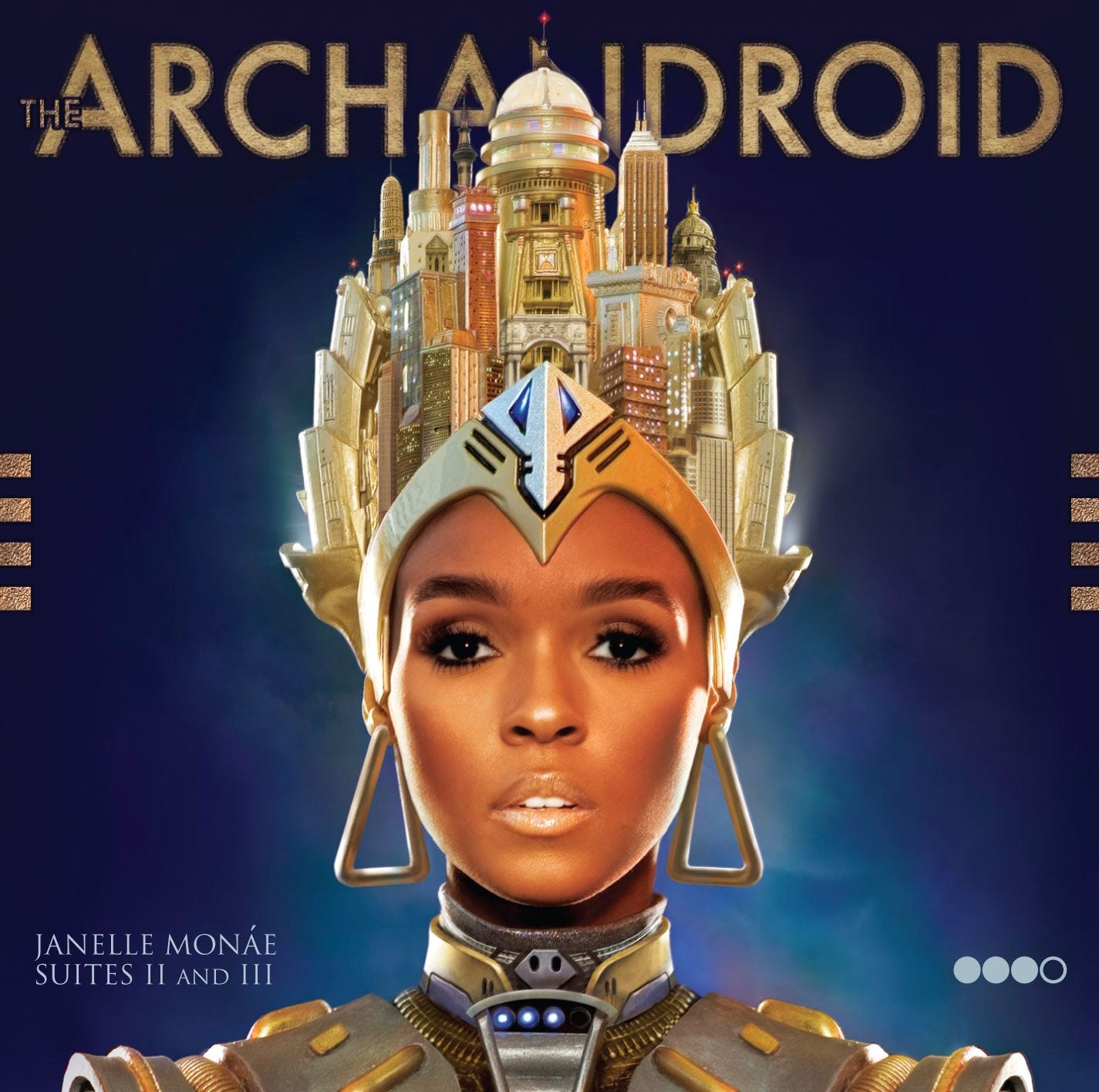

2010: Janelle Monáe, The ArchAndroid

Janelle Monáe crafts an electrifying 70-minute expedition on The ArchAndroid. Their 18-track creation picks up where Metropolis: The Chase Suite concluded, spinning tales of an android messiah across uncharted territories. The music unravels like a cinematic revelation, structured in dual suites with orchestral overtures that mirror a film’s dramatic arc. Their band’s adaptable musicianship anchors each stylistic shift, from R&B’s soulful core to the ethereal territories of British folk, while venturing through psychedelic rock, disco, and theatrical cabaret flourishes. Monáe’s voice morphs effortlessly between gentle whispers and commanding crescendos, yet never eclipses the compositions’ inherent brilliance. They channel the revolutionary spirit of Michael Jackson and Prince while carving their path through contemporary music’s landscape.

2011: Marsha Ambrosius, Late Nights & Early Mornings

Marsha Ambrosius paints shadows and light on Late Nights & Early Mornings, an album that bridges twilight hours with the same soulful intuition that colored her Floetry collaborations. The record sways with unhurried grace, each track draped in velvet arrangements that recall Flo’Ology’s most intimate confessions. Rich Harrison and Alicia Keys help architect the opening sequence, where contemporary quiet storm elements dance with classic R&B foundations. The mood shifts with razor-sharp commentary before unveiling two surprising gems: a spellbinding interpretation of Portishead’s “Sour Times” and a refreshed take on “Butterflies,” her Michael Jackson-recorded composition. Her characteristic vocal tremor appears now like lightning: rare, precise, and impossible to ignore.

2012: Miguel, Kaleidoscope Dream

The ethereal world of Kaleidoscope Dream reveals Miguel’s most intimate reflections. Psychedelic textures intertwine with soul-bearing moments as his voice guides listeners through landscapes of love, doubt, and self-discovery. His decision to craft the album without featured artists creates an uninterrupted journey through his artistic vision. Songs oscillate between dreamy reverie and stark reality, with tracks like “How Many Drinks?” showcasing his ability to blend accessibility with artistic depth. Miguel’s production expertise shines through arrangements that maintain their emotional core despite their technical sophistication. The album captures Miguel at his most honest, crafting songs that float between reality and fantasy.

2013: Janelle Monáe, The Electric Lady

Majesty and revolution intermingle on The Electric Lady, Janelle Monáe’s second full-length masterwork. The orchestral overture sets an ambitious stage, but the intimate moments illuminate their evolution. Within Wondaland’s creative crucible, Monáe and their collaborators forge an alchemical blend of classic soul and avant-garde innovation. Prince’s presence adds royal validation, though the album’s beating heart is Monáe’s quest for connection. “Dance Apocalyptic” bottles pure joy in sonic form, while “Primetime” reveals the vulnerable spirit behind her carefully constructed persona. These twelve songs map the territory between artistic control and emotional surrender. As Monáe grapples with isolation amid acclaim, they transform personal paradox into universal truth. Their music challenges boundaries while remaining grounded in raw humanity, a rare feat confirming their visionary voice position.

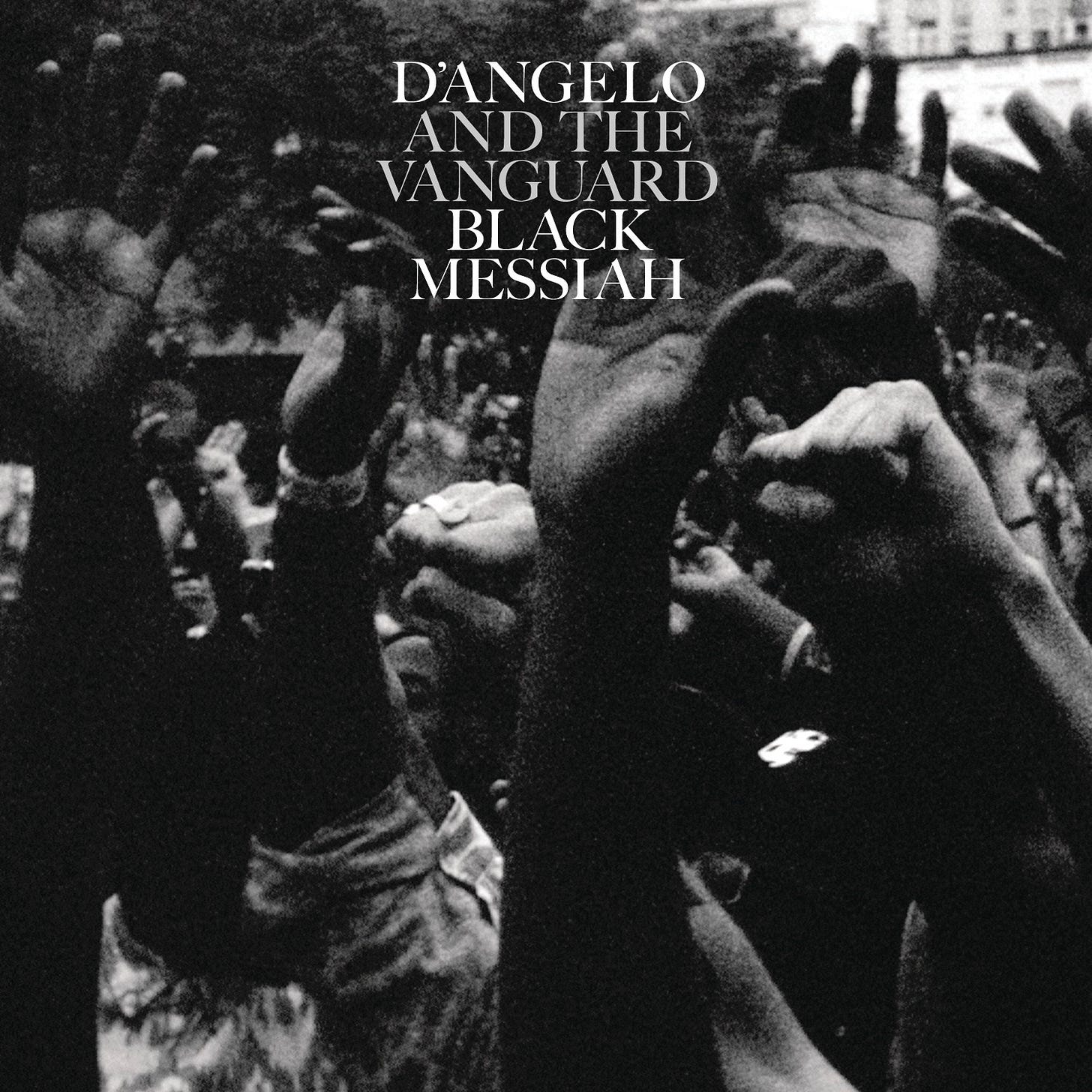

2014: D’Angelo and The Vanguard, Black Messiah

After fourteen years of radio silence, D’Angelo’s Black Messiah has finally arrived as an artistic revelation dismantling musical orthodoxies. Rather than a spontaneous creation, these compositions crystallize from prolonged creative gestation. His earlier masterwork, Voodoo, had established his R&B sovereignty, yet the accompanying fame drove him toward solitude. During his self-imposed exile, D’Angelo refined his artistry through selective collaborations, expanding his musical vocabulary. The resulting Black Messiah radiates with untamed funk arrangements, psychedelic textures, and rock-infused textures, all bearing his distinctive fingerprint. He transforms disparate musical elements into revolutionary harmonies through calculated discord and genre-bending alchemy.

2015: Jazmine Sullivan, Reality Show

Raw emotion radiates through each note as Jazmine Sullivan strips away the glossy veneer of conventional R&B. Her voice, once wielded like a weapon, now whispers and beckons with calculated restraint. Marching pacing collides with disco grooves; Reality Show paints an aural canvas that shifts and morphs with mercurial grace. Behind every measured pause and controlled crescendo lies a master class in storytelling—each character sketch etched with psychological depth and nuanced observation. These aren’t mere songs but intimate confessionals where wisdom earned through heartache illuminates universal truths. Sullivan’s distinctive tone cuts through the mix like a beacon, guiding listeners through labyrinths of love, loss, and self-discovery. Her narratives unfold like short stories, rich with detail yet open to interpretation, as she crafts portraits of resilience and moral conviction.

2016: KING, We Are KING

Three voices united under the banner of KING in 2011, releasing an EP that merged electronic innovation with soul tradition. Their harmonies floated like cosmic dust through carefully programmed soundscapes, echoing Wonder’s backing singers while charting new astronomical paths. Fellow musicians recognized their unique frequency, leading to creative cross-pollination across genre boundaries. Between periodic single releases, KING perfected their craft in monastic dedication to sonic detail. Their 2016 album We Are KING chronicles this patient evolution, expanding earlier works while introducing fresh compositions that push their aesthetic toward new horizons. Their production philosophy prizes precision—each electronic pulse and vocal layer is calculated for maximum emotional impact. Spiritual and romantic narratives interweave throughout these tracks, reaching toward transcendence in their musical meditation on Ali’s eternal spirit. While maintaining their core sound, every moment reveals new facets through subtle innovation and careful refinement.

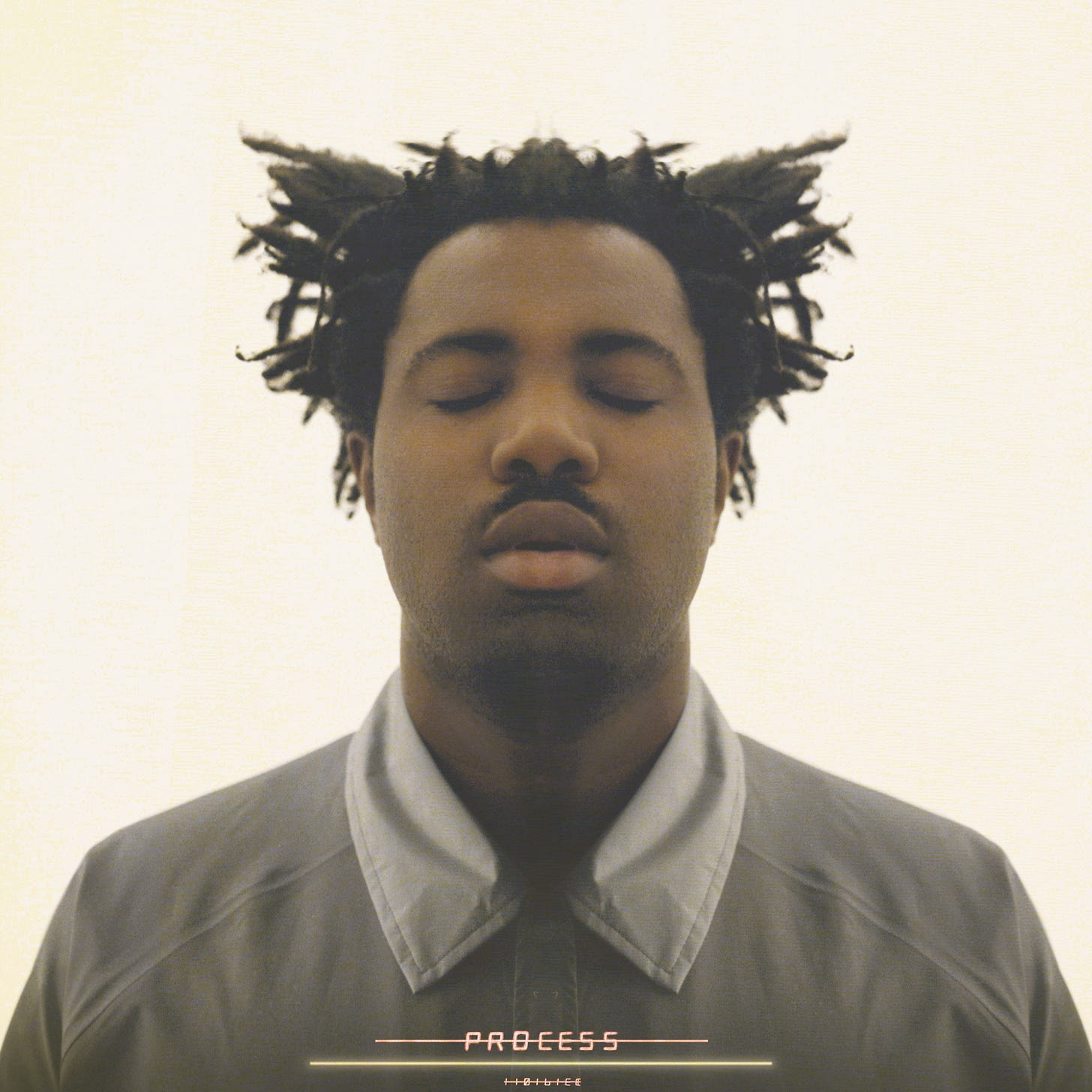

2017: Sampha, Process

A piano in Morden, England, became young Sampha Sisay’s sanctuary, a gift from his father that would shape his musical destiny. On his first full-length album, Process, raw emotions pour through each note as Sampha confronts the ghosts of personal tragedy. His gentle falsetto carries the weight of losing both parents while battling his health crisis, transforming private anguish into a universal truth. The record’s marriage of electro-soul and hip-hop elements mirrors this metamorphosis, breaking away from his previous supporting roles alongside celebrated collaborators. Each track unfolds like pages from a diary, chronicling isolation’s grip and grief’s endless echo. When the final notes fade, Sampha’s homecoming feels less like a retreat and more like a revolution, a prodigal son returning to remake himself through music’s healing touch.

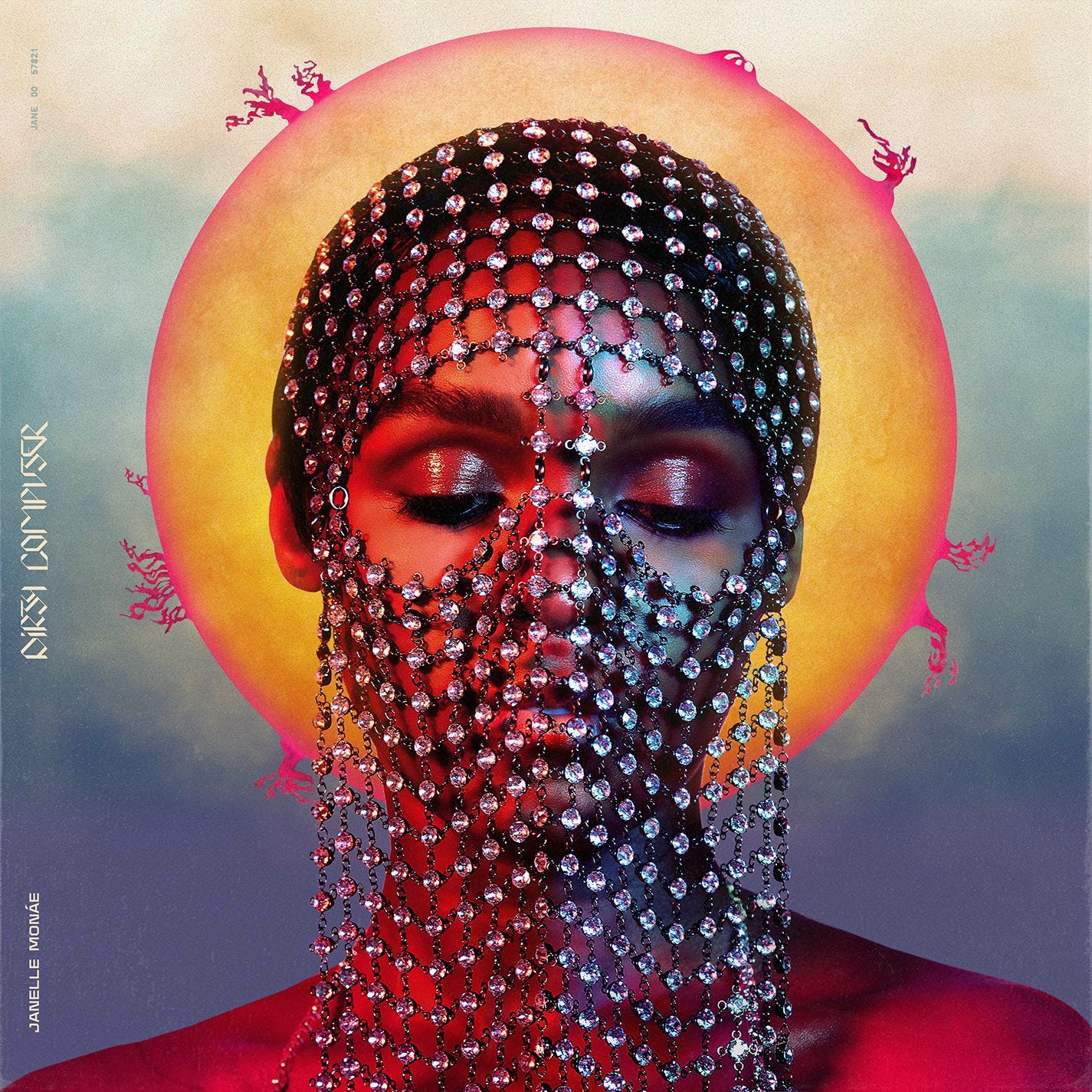

2018: Janelle Monáe, Dirty Computer

A revolutionary spirit exudes through Dirty Computer. Janelle Monáe crafts an electrifying fusion of R&B, pop magnetism, and funk-laden grooves, wielding their voice as both weapon and balm. Each note pulses purposefully, from the thunderous percussion to the gleaming synthesizers that paint their new wave aspirations. The lyrics burn with self-assured conviction, especially during “Django Jane,” where Monáe’s razor-sharp wordplay cuts through oppressive systems. Their collaborations with Brian Wilson, Stevie Wonder, and Grimes add distinctive colors without overshadowing the singular vision Monáe shares with their Wondaland collective. This musical revolution speaks to marginalized voices while commanding mainstream attention through pure pop genius.

2019: Raphael Saadiq, Jimmy Lee

Pain echoes through every corner of Jimmy Lee as Raphael Saadiq excavates family trauma with surgical precision. His brother’s story becomes a lens for examining addiction’s ripple effects across African-American communities. The polished sheen of earlier works cracks intentionally, revealing raw nerves beneath. “Kings Fall” and “Rikers Island” ring with urgent truth, while “My Walk” charts bold new sonic territories. Saadiq’s masterful arrangements create space for darkness and light, transforming personal grief into universal understanding. Each track builds upon the last, bridging individual suffering and collective healing.

2020: Lianne La Havas, Lianne La Havas

Armed with just six strings and limitless imagination, Lianne La Havas creates musical alchemy on her self-titled release. Her interpretation of “Weird Fishes” reconstructs Radiohead’s architecture with soulful intuition, while “Bittersweet” burns quietly. Taking cues from the pioneering spirit of Hejira, songs like “Can’t Fight” and “Green Papaya” showcase her masterful guitar work and arranging skills. The devastating simplicity of “Paper Thin” proves that sometimes less yields more. La Havas maintains a perfect equilibrium between ornate arrangement and stark simplicity throughout the album, creating timeless and modern music.

2021: Cleo Sol, Mother

Parenthood opens new creative pathways for Cleo Sol’s Mother, where extended musical forms mirror life’s expanding horizons. The Fender Rhodes keyboard creates protective musical cocoons while her voice explores the full spectrum of maternal experience—from rapturous joy to quiet reflection. Moving beyond her SAULT collaborations and early solo work, Sol partners with Inflo to craft arrangements that nod to soul pioneers Stevie Wonder and Charles Stepney while speaking their truth. Each composition breaks from standard song structures, allowing her to explore the subtle shades between genres. Her vocal control becomes a tool for storytelling, drawing lines between personal history and present transformation, weaving together threads of generational understanding.

2022: Sudan Archives, Natural Brown Prom Queen

Sudan Archives rewrites the narrative about Black women’s musical capabilities. Through Natural Brown Prom Queen, Brittney Parks demonstrates how self-taught expertise can revolutionize contemporary sound. The Ohio artist’s 18-track collection merges avant-garde pop sensibilities with hip-hop’s foundation and electronic innovation, creating music that resonates emotionally and physically. In “Home Maker” and “NBPQ (Topless),” Parks confronts personal demons with raw authenticity, her words alternating between doubt and empowerment. Her distinctive approach combines Sahel-inspired violin melodies with modern beats and rhythmic complexity, establishing an unprecedented musical language.

2023: Victoria Monét, Jaguar II

Victoria Monét conjures magic on Jaguar II by threading golden memories through contemporary fabric. Her harmonies echo family reunions where Earth, Wind & Fire classics filled the air with joy. The production gleams like five-star hotel lobbies, each track flowing seamlessly into elegant musical chambers. Between verses dripping with timeless sensuality and modern confidence, she drops hooks that tattoo themselves on your consciousness. Her genre-bending expertise shines as she mixes dub waves with Houston rap currents, never losing her artistic center. This musical alchemy honors R&B’s pioneers and announces Monét as a vital voice in its future.

2024: Lucky Daye, Algorithm

Producer D’Mile helps Lucky Daye architect a soulful sanctuary on Algorithm, where fourteen tracks blur the lines between past and present R&B. Live instruments paint rich textures beneath Daye’s agile vocals, creating an atmosphere that shifts from shadowy lounges to sun-drenched block parties. His falsetto expertise illuminates “Diamonds In Teal” and “HERicane,” while his groove-heavy compositions pay homage to Nile Rodgers’ legendary touch. The album’s first half sparkles with particular brilliance, where live instruments create an organic foundation for Daye’s complex songwriting. Though some meditations on modern love can lack focus for some people, his catchy melodic tunes make up for it as the yearning for “Blame” completion lingers. Lucky hits a home run with a three-peat.

Yes, I love this, and I agree with a lot of these. I'm excited to dive into some of the pre-1960s albums you listed because that's an R&B era I don't listen to as often. Now *cracks knuckles* below are a few of my picks that would've been different,

1980 - I would've picked Stevie Wonder's Hotter Than July over Diana -- Diana feels more pop/disco than R&B.

1996 - I LOVE Urban Hang Suite, but Aaliyah's One in a Million was ahead of its time and completely changed the sound of R&B (especially how it sounds today), whereas UHS was an expansion on neo-soul (which I consider more of an era than a genre).

1999 - Meshell Ndegeocello's Bitter also feels more neo-soul than R&B and sonically, is not that dynamic, I would've selected Where I Wanna Be by Donell Jones.

2003 - I promise I'm not a Meshell Ndegeocello hater, but Ashanti's debut album, Southern Hummingbird by Tweet, and The Diary of Alicia Keys were all more memorable R&B albums from that year for me.

All the albums you listed from 2004-2015 were spot on.

2016 - I love that KING album, butttt 2016 belonged to A Seat At The Table by Solange, that album was a cultural reset that will be discussed for years to come.

2017 -- CTRL by SZA was the R&B album of that year. Some of the tracks leaned more alt/pop, but when she tapped into R&B, she really gave us that classic feeling in a way Sampha never has.

2018 - Dirty Computer is my least favorite Janelle Monae album. I think too many people slept on Isolation by Kali Uchis that year.

2019 - My personal favorite was When I Get Home by Solange, but I also think Ari Lennox's Shea Butter Baby could've been a contender here.

2020 - I LOVE Lianna La Havas, but that album did not heal me like Rose in The Dark by Cleo Sol did.

Side note: thank you for including Leave it All Behind by The Foreign Exchange because that album was incredible and doesn't get discussed enough.

no new edition the disrespect was real