The Best R&B Music of 2025 (So Far…)

This year didn’t deliver too many standouts in the mainstream. However, on the other side, they sketch a panorama of R&B’s present, rooted in tradition, and restless in execution.

The first half of 2025 has felt like a deep breath after 2024’s nonstop sprint. The marquee names who dominated last year’s headlines, from Beyoncé’s Grammy-hoarding Cowboy Carter cycle to a flood of mid-tier comeback records, have mostly gone quiet, leaving the mainstream calendar unusually thin. Yet the lull hasn’t meant stagnation. Instead, a crop of fiercely personal projects has stepped into the open space, tracing R&B’s living roots (soul, gospel, neo-funk, bedroom pop) while yanking those roots into riskier, restless shapes. Lists that track the year’s best releases already tilt toward these left-of-center statements rather than blockbuster tent-poles. 2025 may not have logged its blockbuster yet, but its most compelling voices are proving that invention thrives in the breathing room between cultural flashpoints.

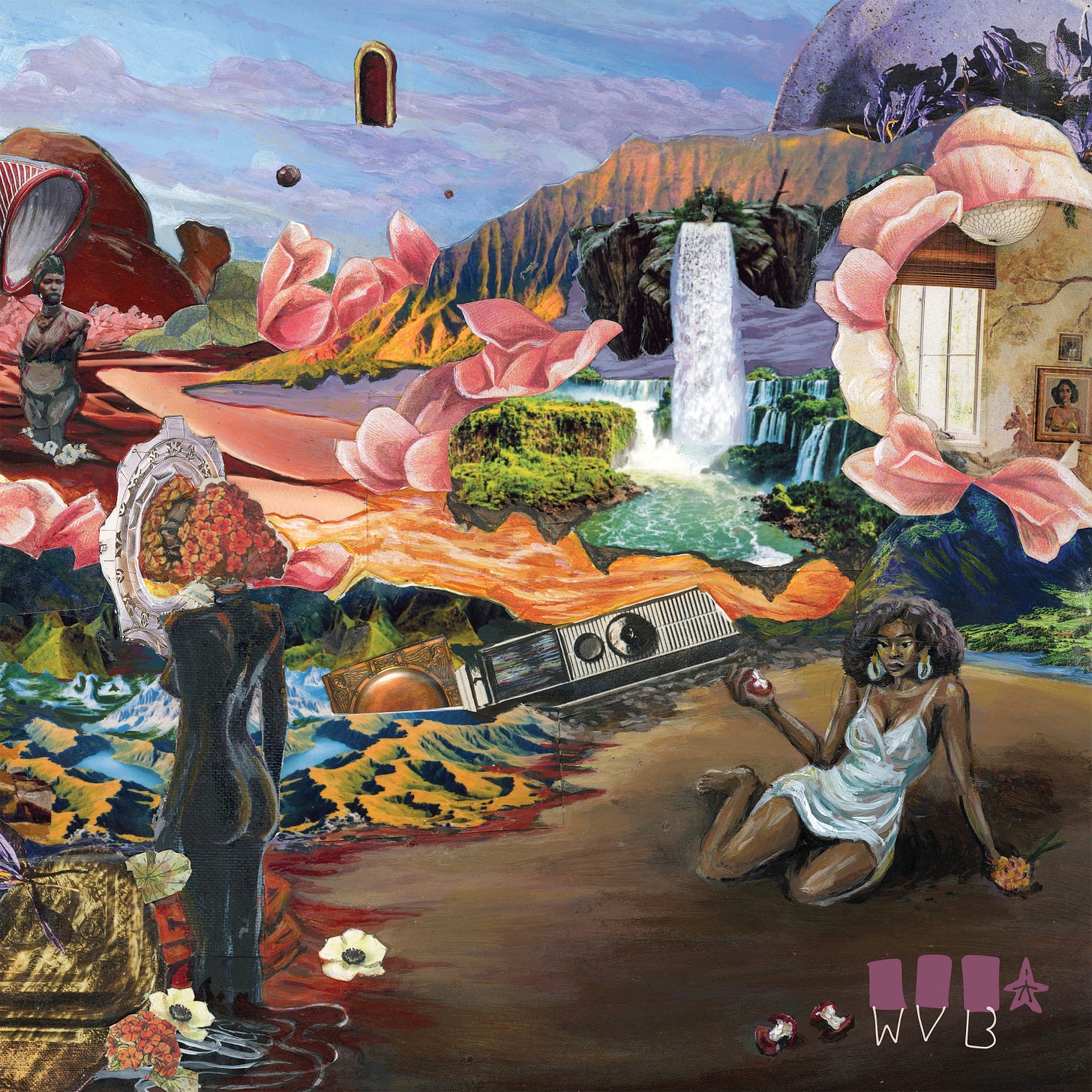

SAULT, 10

SAULT are so unpredictable. Their latest stealth drop opens with clipped, initial-only titles that read like coded mantras, reinforcing the collective’s insistence on message over celebrity. “T.H.” sets the tone with a polyrhythmic drum kit swirling around an electric-piano vamp before a children’s choir enters, turning the groove into affirmation rather than mere jam. Throughout the album, producer-architect Inflo layers live bass, hand percussion, and orchestral swells; on the mid-tempo “P,” a rubbery bassline locks with rim-shot snares while stacked vocals trade phrases that blur the line between call-and-response and internal dialogue. SAULT’s habit of releasing then briefly deleting music intensified the album’s mystique when it appeared on Good Friday, vanished, and returned on Easter Sunday—a resurrection gesture that matches the record’s themes of endurance and spiritual rebirth. Yet 10 isn’t pious; “S.I.T.L.” runs an Afro-disco pulse under dubby guitar stabs, and “W.A.L.” floats a lilting West African high-life line over rousing congas, as if stitching together a diasporic sound quilt. SAULT’s anonymity ultimately spotlights that pan-Black conversation in the music itself—a conversation that feels urgent, communal, and insistently hopeful. — Phil

Terrace Martin, Albion Files

Martin raided hard-drive archives dating back to the mid-2000s beat experiments, routing dusty MPC loops through contemporary horns and vocoders so each track feels both archival and immediate. “Full Speed” ignites the ride with DRAM’s falsetto stacked over a talk-box hook while A$AP Ferg drops punch-line couplets that glide across phasing synth-bass; the chorus lands on a half-bar rest that makes the downbeat feel seismic. “My Saturday” has Tone Trezure’s smoke-curl alto floats above brushed snares, Fender Rhodes stabs linger on the off-beat, and a flute shadow-dances behind the chord changes. The album’s midpoint cools with “Valdez,” whose ribbon-mic’d trumpet phrases blur into cassette hiss while a sub-bass groove barely breaks ninety beats per minute. “Not Sharing” pairs Ogi’s sharp-edged delivery with guitar-wah smears that recall West-Coast g-funk yet resolve in altered-dominant chords straight from modal jazz. “Albion Way” strips the drums, letting muted trumpet notes hang until tape-flutter swallows them; the silence that follows feels earned, as though the party lights just snapped off and the amps are cooling. — Murffey Zavier

Bootsy Collins, Album of the Year #1 Funkateer

Bootsy’s latest carnival opens with a thunderclap of clavinet, talk-box chatter, and a bass line dirtier than a P-Funk tour bus floor. One moment he’s dropping a tight “on-the-one” homage in “The JB’s Tribute Pastor P,” weaving Clyde Stubblefield’s drum DNA around rapid-fire rhyme cameos; the next he’s leaping into “Bubble Pop,” a synth-doused slice of space-disco where his slap bass ricochets off laser-beam guitar licks. Even the zaniest detours—metallic shred workouts, cartoon skits about AI gone rogue—are glued together by that rubbery low-end tone that could only come from the star-shaped Space Bass. Yet beneath the jokes and psychedelic FX is a living history lesson. Bootsy threads gospel shout-outs, G-funk hand-offs, and sly Afro-beat nods into a single revue, treating funk less as a genre and more as an eternal renewable resource. Guest spots are deployed like fireworks, but Collins remains ringmaster, his bass anchoring each side quest while his falsetto ad-libs remind you fun is sacred business. In doing so, he reasserts why his fingerprint has never faded from modern groove music. — Harry Brown

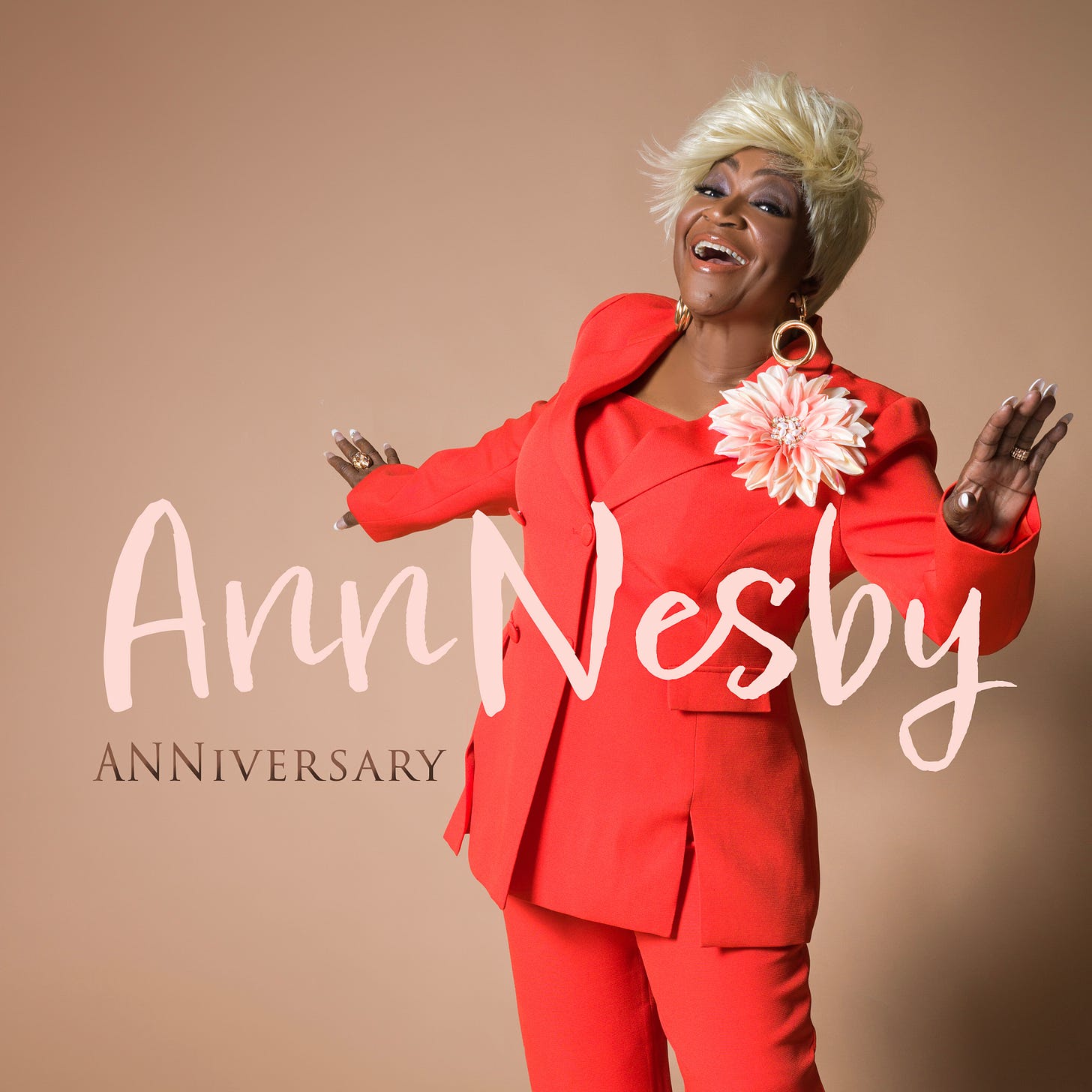

Ann Nesby, ANNiversary

Thirty years after fronting Sounds of Blackness, Ann Nesby’s voice still cuts through any mix with a warm, clarion, and built to testify. ANNiversary frames that instrument in arrangements that pivot from Memphis-style Southern soul to contemporary quiet-storm elegance. “Missin’ You” rides a churchy Hammond organ figure into a snappy shuffle that lets her push and pull against the backbeat, savoring blue notes on every turnaround. When the tempo slows for “Still,” the production drops to murmuring Rhodes and brushed drums; Nesby fills the space with melismatic runs that resolve not into showy climaxes but into conversational sighs, underscoring lyrics about steadfast partnership. She peppers the record with spoken-word asides—small sermonic interludes that recall her gospel roots without turning the album into a praise-and-worship set. The cumulative effect is less “nostalgic comeback” than a master class in phrasing from a singer who understands that restraint can shout just as loudly as sheer power. Closing cut “Safe Space” marries bluesy guitar chanks to layered counter-melodies, her ad-libs spiraling upward as if sketching the safe space she’s singing about into existence. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Galactic & Irma Thomas, Audience With the Queen

Irma Thomas proves her voice remains a commanding force at 83 on Audience With the Queen. Her career, launched with a hit in 1959, has made her one of the city’s most iconic figures, a GRAMMY-winning artist whose influence stretches across decades and genres. On this album, Thomas channels that strength into a range of expressions—love ballads, political declarations, and songs that lift the spirit with purpose. Take “How Glad I Am,” a cover of Nancy Wilson’s 1964 classic. She infuses it with a gospel depth that nods to her church roots, turning a familiar tune into something distinctly her own. Then there’s “Over You,” a pulsing track where Thomas wrestles with the aftermath of a failed romance, her vocals cutting through Galactic’s tight, funky arrangement. Galactic, a mainstay in New Orleans for 30 years, brings their signature mix of blues, jazz, and that unmistakable local funk, providing a modern foundation that complements Thomas’s classic soul sound. This album arrives at a moment when the music world often mourns greats after they’re gone. Instead, Audience With the Queendemands recognition for Thomas now, a living legend whose work continues to shape the Crescent City’s musical identity. Her collaboration with Galactic underscores the importance of honoring artists in their time, ensuring their contributions resonate while they can still hear the applause. — Imani Raven

Durand Bernarr, Bloom

Bernarr has long balanced irreverent humor with devotional singing, and Bloom finds that equilibrium fully mature. The record’s opening salvo “Generous” glides on a plush synth-bass pocket while his falsetto flips between coy invitation and gospel-esque ad-libs, illustrating how secular desire and sanctuary can occupy the same breath. Elsewhere, “Flounce” recruits New Orleans bounce cadences to tell off energy vampires with a grin, a reminder that self-protection can sound like a block-party chant rather than a stern lecture. Even the quiet-storm ballad “Unspoken” refuses to chase respectability, breaking into conversational asides as though Bernarr can’t help but let them see the thoughts forming in real time. Across the album, stacked harmonies nod to the singer’s background touring with Erykah Badu, yet the production prefers glossy keyboard chords and sub-bass pulses to retro re-creations, planting his vintage phrasing firmly in the digital now. The result feels like a house-party sermon delivered by your funniest friend—profane, kind, and impossible to tune out. — Jamila W.

Annie & The Caldwells, Can’t Lose My (Soul)

The West Point, Mississippi family group spent decades singing in roadside sanctuaries before Luaka Bop wired up a mobile studio inside New Home #2 Missionary Baptist Church to capture their “disco-soul gospel” in two weekend sessions. Annie Caldwell’s daughters arrange three-part harmonies that glide over guitar lines soaked in phase-shift—an echo of their teenage love for Chic records smuggled into rehearsal under the pews. The ten-minute centrepiece “Can’t Lose My Soul” modulates from 6/8 testimony into four-on-the-floor praise without losing the raw hand-clap ambience that producer Matt Colton left unedited to preserve sanctuary bleed. The album chronicles marital doubt, working-class exhaustion, and spiritual stubbornness, yet every chorus doubles as a promise: “wring my heart, but the melody stays clean,” Annie growls, turning hardship into groove. — Imani Raven

Ledisi, The Crown

Ledisi’s twelfth outing radiates the focused assurance of a vocalist who trusts her tools. The title track frames brass stabs around an effortlessly floated top-line, but the lyric centers self-worth rather than triumphalism, turning the hook into a benediction for anyone who has felt unseen. That sense of vocation deepens on “BLKWMN,” where marching-band snares underline her inventory of joys and burdens specific to Black womanhood; when the arrangement drops to just organ and voice on the bridge, Ledisi’s melismatic runs feel less like vocal showpieces than spiritual exhalations. Mid-tempo cut “Good Life” pivots into pocket-groove R&B, its stacked background vocals recalling gospel quartets even as the chord changes flirt with jazz diminuendo. Throughout, the writing avoids inspirational boilerplate by foregrounding the process where hope is earned, not handed down. — Imani Raven

Your Grandparents, The Dial

The trio stretches a single metaphor—the telephone—as a portal through memory, desire, and altered consciousness. The set opens with the title piece, a stuttering break-beat and woozy Rhodes that bleeds directly into “All Dem Times,” where rumbling sub-bass underlines stacked harmony lines reminiscent of late-‘90s L.A. neo-soul sessions. Mid-sequence, “Tea Lounge/Blossom” unfurls in two movements: first a brittle drum-machine shuffle, then a flute-laced psychedelic bridge featuring singer Iyana that recalls Shuggie Otis’s liquid guitar phrasing. The trio’s rapper–crooner interplay peaks on “Hypnotized,” trading sing-song cadences with Belgian duo blackwave. over a clavinet riff that could have spun out of George Clinton’s vault. Closer “Down” rides a chopped-and-screwed chant toward silence, completing a cycle that feels like hanging up the cosmic receiver. — Reginald Marcel

Michi, Dirty Talk

Written after Michi decamped from L.A. to a quiet seaside town to “move with [her] natural emotional circadian rhythm,” Dirty Talk treats solitude less as retreat than as laboratory. She converts the debris of a bruising breakup into gauzy, bilingual R&B that alternates between candle-lit confession and dance-floor release. The record’s backbone—co-production by Blake Rhein and Paul Cherry, with mastering from Jake Viator—wraps nylon-guitar flourishes, Rhodes clusters, and sub-bass pulses in a vinyl-warm mix that salutes ’80s and ’90s soul without embalming it in nostalgia. By the closer “Way I Do,” Kiefer’s jazz piano arpeggios coax Michi into a fragile falsetto run that dissolves before it fully forms, underscoring a record fascinated by what happens in the split-second between courage and retreat. — Phil

Southern Avenue, Family

Memphis-bred but globally inclined, the band tracked these songs live after a month-long residency at Stax Museum’s soundstage; that room’s slapback bounce colours every snare hit. Opener “Long Is the Road” drapes churchy organ over Israeli guitarist Ori Naftaly’s blues bends, while Tierinii Jackson sings about ancestors “humming freight-train keys.” “Found a Friend in You” slides from gospel shuffle into Afro-beat breakdown—a nod to bassist Evan Sarver’s Nairobi childhood—without losing hand-clap grit. The title cut turns a simple three-chord vamp into a call-for-unity anthem; the repeated refrain “blood is a tune, not a chain” underscores the album’s fixation on chosen kinship. — Jill Wannasa

Mourning [A] BLKstar, Flowers for the Living

The Cleveland collective’s newest is equal parts funeral dirge and liberation hymn. Opener “Stop Lion 2” fuses distorted bass drone with a field-recorded Baptist shout, interrupted by a spoken-word salvo from Lee Bains that sounds like Gil Scott-Heron channeled through post-punk megaphone. Elsewhere, “Letter to a Nervous System” layers tape echo on dour trumpet lines, evoking the echo-chamber anxiety of the album’s title. Yet hope persists: closer “88 pt.” hinges on a modal, Major-7th guitar vamp that brightens each chorus, suggesting blossoms pushing through concrete. Multiple lead vocalists trade lines like communal testimony, transforming grief into collective propulsion. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Mychelle, Good Day

Mychelle wrote much of this set on late-night London buses, capturing voice notes of engine hums she later pitched into sub-bass under tracks like “Seasons,” a ballad that compares emotional cycles to Brixton’s shifting storefronts. “Sweet Nothings” blends finger-picked acoustic guitar with clipped, drill-like hi-hats; her lyric, “silence is a cloud I rent by the hour,” crystallizes the record’s balance between spacious production and internal monologue. The title track turns sunrise optimism into subtle protest: horn stabs land slightly behind the beat, mirroring the singer’s line “they pawn our daylight, sell it back in neon.” Throughout, layered backing vocals form a soft chorus of self-reassurance rather than traditional call-and-response, reinforcing the album’s theme of privately cultivated resilience. — Phil

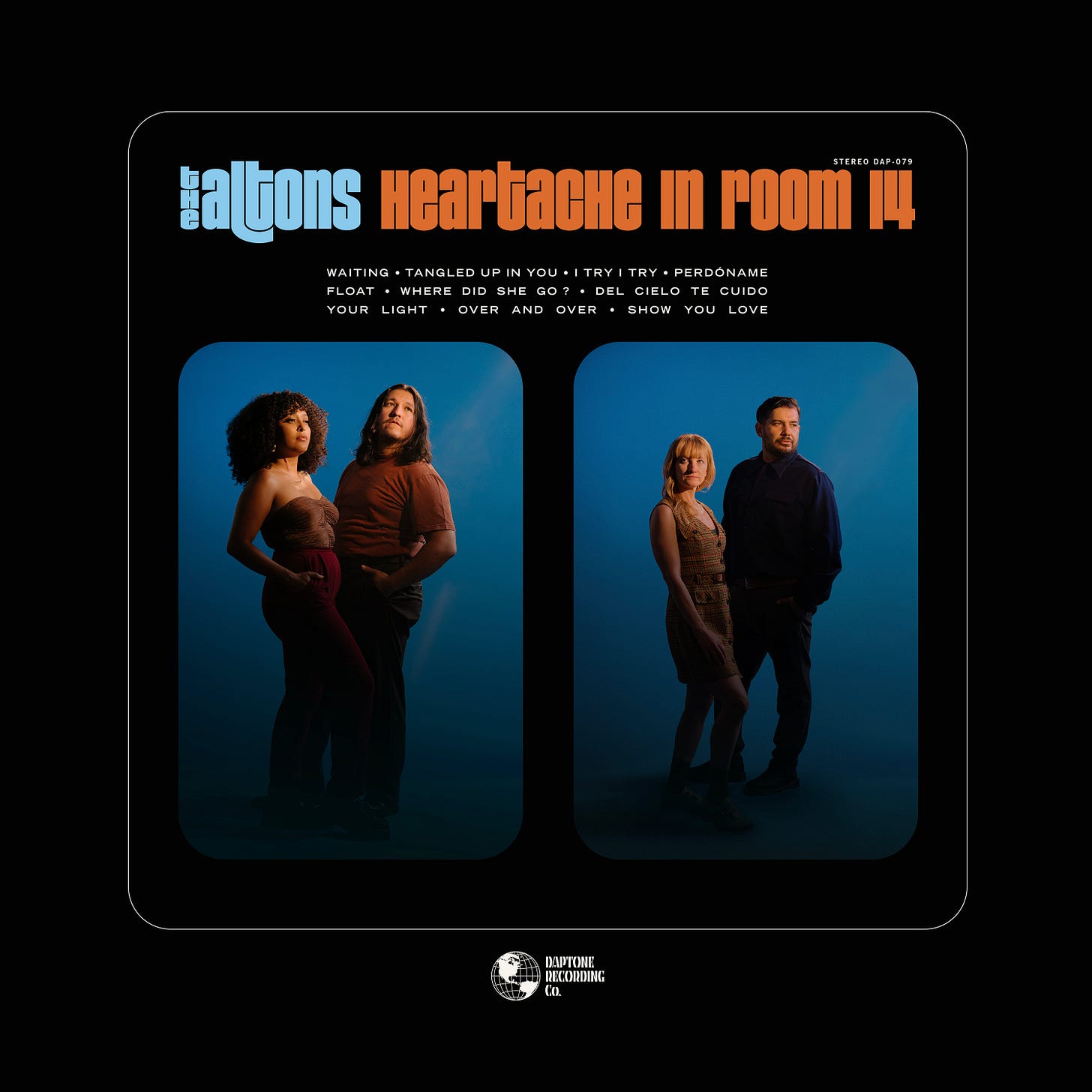

The Altons, Heartache In Room 14

The Southeast‑L.A. quintet tracked the album straight to tape with label boss Gabriel “Bosco Mann” Roth, letting every tambourine shake and guitar‑amp hiss land with analog warmth. Dual vocalists Adriana Flores and Bryan Ponce trade verses like a soul‑cinema couple locked in the same motel room the title references, recalling Marvin & Tammi one moment and Los Panchos boleros the next. The set shape‑shifts with “Waiting” that rides a mid‑tempo Northern‑soul beat; “Perdóname” pivots to bilingual doo‑wop; while “Float” laces a Spaghetti‑Western guitar line over low‑rider percussion. Throughout, Roth keeps the grooves bone‑dry, foregrounding the band’s signature Latin‑soul congas and Byrds‑like twelve‑string shimmer. It’s a breakup record that never wallows—closer “Show You Love” ends on a redemptive falsetto‑soaked vamp that nods to the Daptone family ethos of finding light inside grit. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Joe Kay, If Not Now, Then When (EP)

Soulection co‑founder Joe Kay built his global brand by curating other people’s tracks; here, he finally curates himself. The six‑song EP flips the collective’s signature future‑soul palette into autobiographical mood‑pieces that dart from dubwise low end to airy Rhodes chords. Kay describes the project as “a postcard from the process of learning to show up for myself,” and he literalizes that mantra by stacking communal vocals—Amaria, Arin Ray, Sinéad Harnett—around his own understated talk‑sing delivery. “Laguna Loop” welds pattering Afro‑beat percussion to cracked‑open diary entries about friendship fatigue, while “Venice Midnight” rides gospel organ until it dissolves into hiss like a cassette left on the dashboard. The sequencing feels radio‑show intentional—each track segues with vinyl‑crackle bumpers—and by the time the closer drifts out on wind‑chime synths you’ve absorbed a sonic philosophy: curiosity over perfection. Worth a listen for production heads who enjoy hearing the DJ move from selector to subject. — Brandon O’Sullivan

NAO, Jupiter

NAO’s fourth LP orbits joy as both theme and method, opening with “Wildflowers,” a candied slip-n-slide of syncopated bass slaps and stacked harmonies that recall the playful polyrhythms of her early EPs while injecting newfound ease. Throughout, the songwriting alternates between dance-floor rapture—“Happy People” piles rubbery Moog riffs under a chant-ready chorus—and nocturnal slow jams like “Elevate,” where clipped hi-hats tick beside pillow-soft synth pads as NAO’s soprano melts into airy head-tones. She threads cosmic symbolism—Jupiter as planet of abundance—through plainspoken declarations: “We all win /when light gets in,” she repeats over gospel-tinged stacked vocals on the mid-tempo standout of the same name. Even the ballad “Light Years” resists drift; hand-played Rhodes chords bend micro-tonally at phrase endings, suggesting gravitational wobble in the song’s astronomy metaphor. NAO’s hallmark is contrasts—helium falsetto against murky sub-bass, sugary hooks against knotty rhythm changes—and Jupiter refines that balance until it feels as natural as breathing in and out. — Tai Lawson

Eddie Chacon, Lay Low

Thirty years after his pop-soul heyday, Chacon writes with the unhurried clarity of someone who has made peace with silence. Producer Nick Hakim surrounds him with soft-focus synth pads and reverb-ghosted percussion, yet every track leaves wide air-pockets so the singer’s barely-there tenor can brush past your ear like late-afternoon wind. “Good Sun” tethers childhood memory to minimalist drum-machine clicks, the melodic arc rising only to fall back into murmured resignation; it’s heartbreak rendered in lowercase, more diary than aria. Conversely, “Empire” rides a glimmering, almost Balearic groove, letting Chacon test the upper corners of his range in gentle falsetto exhalations that never break the record’s sleepy hush. Throughout, the thematic through-line is surrender; it’s not defeat, but the relief of loosening one’s grip on the stories we teach ourselves about control. By trusting restraint over retro histrionics, Lay Low becomes a quietly radical entry in modern soul—proof that aging out of pop spectacle can unlock braver, sparer kinds of honesty. — Jamila W.

Destin Conrad, Love On Digital

Conrad’s debut album begins with “Kissing in Public,” a Neptunes-inspired joint that sets intimacy as a public-facing gesture rather than a secret act. Sequenced like an endlessly scrolling feed, the 15-track run keeps songs tight—few crack four minutes—mirroring the swipe-culture attention span it interrogates. The centerpiece, “Soft Side” featuring serpentwithfeet, floats Conrad’s unguarded tenor over reversed-piano swells; serpentwithfeet punctuates the bridge with gospel-choir-worthy melisma, turning vulnerability into duet communion rather than confession. On “Bad Bitches!” Kehlani’s dusky mezzosoprano dovetails with Conrad’s upper register over a low-end that rattles like a subwoofer in the trunk of a late-night Uber; the lyric flips objectifying language into a self-affirming call-and-response, rendering bravado a collective shield for marginalized desire. Teezo Touchdown crashes “The Last Time” with distorted pop-punk ad-libs, exposing cracks beneath Conrad’s polished delivery and emphasizing the album’s through-line where real connection in an era where every feeling risks becoming content. — Jamila W.

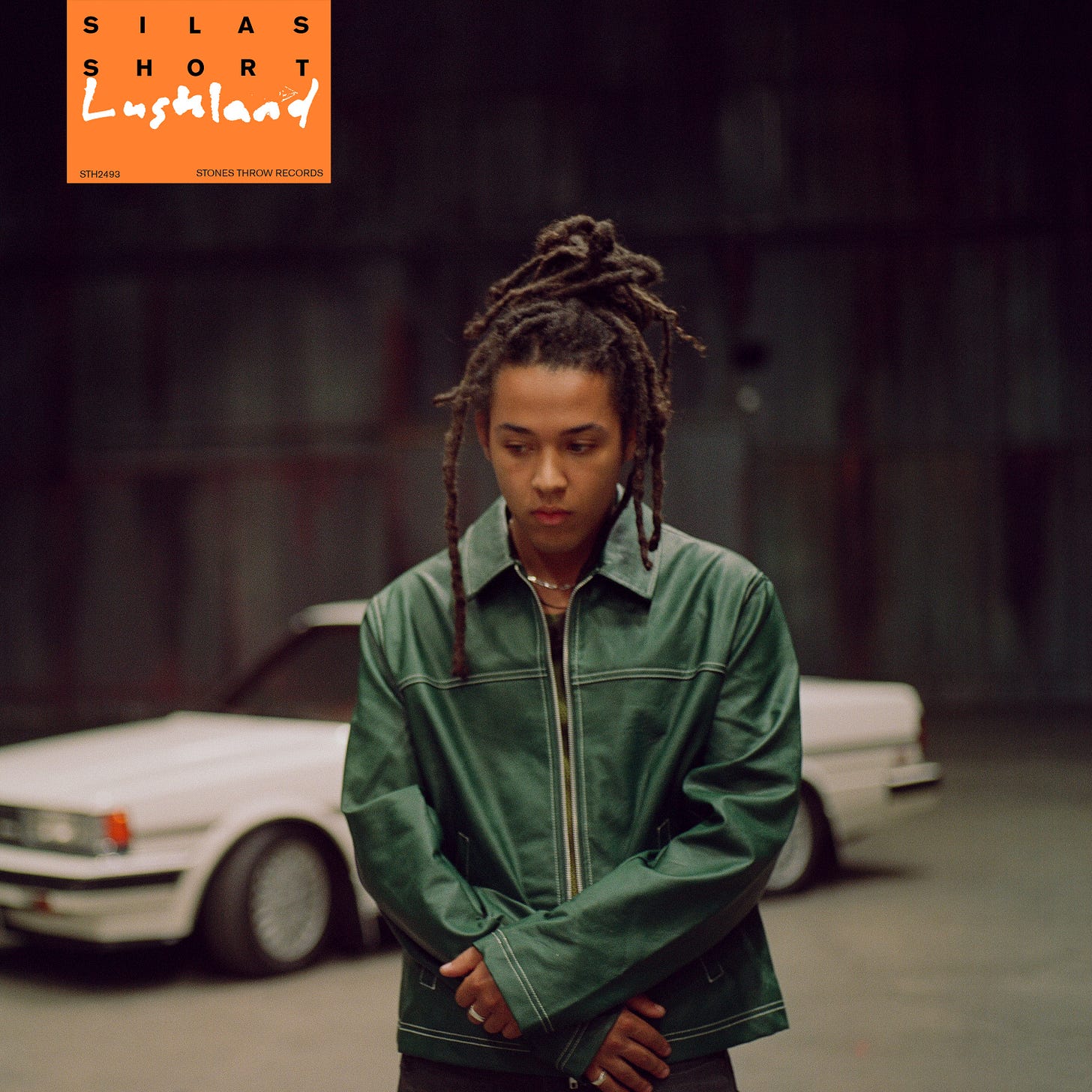

Silas Short, Lushland

Silas Short records soul music the way painters layer watercolors, featuring translucent strokes after translucent strokes until depth sneaks up on you. From opener “Justa Dream,” finger-picked electric guitar, brushed drums, and tape-echo vocals form a pocket so hushed that every string squeak counts as percussion, asserting intimacy as a compositional tool. Short’s self-described “liquid-style” guitar playing—developed after breaking a hand in his teens—lets him slide micro-intervals between chords, giving tracks like “Ph0necall” the fluid harmonic feel of early D’Angelo without the latter’s overt funk punch. The title cut swells from whispered verse into towering choir-like refrains, but he starves the snare of reverb so each hit sounds like a finger tap on a kitchen table, translating grand emotional reckoning into bedroom-studio scale. Lushland knits together tales of relocation, fear of failure, and guarded optimism; “Pass On By” croons, “Dreams ain’t cheap/But neither are regrets” over muted trumpet flourishes that fade before resolving, underscoring the record’s fascination with decisions suspended in mid-air. — Harry Brown

Tanika Charles, Reasons to Stay

Tanika Charles sings like she’s opened every wound just wide enough for the groove to cauterize it. Her fourth LP trades previous rom-com heartbreak narratives for familial fault-lines, stacking Chi-Lites-style string swells and clipped hi-hat shuffles against lyrics that name-check abandonment, reconciliation, and inherited shame with unflinching clarity. “Don’t Like You Anymore” drapes smoky B-3 chords over a head-nodding pocket, her phrasing dipping into husky low notes before vaulting into a trembling melisma that cracks exactly where the story does. Producer Scott McCannell and mixer Kelly Finnigan infuse every rim-click and tambourine shake with analog hiss and ribbon-mic saturation, lending mid-tempo burners like “Talk to Me Nice” the warm, vintage sound of a lost 1973 acetate without ever sounding like a costume. When Clerel’s smoky tenor enters on the Gamble-and-Huff-tinged “Win,” the arrangement briefly slips into woozy psychedelic gospel before returning to its neo-soul core—a reminder that Charles, even in her most vulnerable confessions, never lets the pocket drift. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Ben L’Oracle Soul, Sad Generation

Now a decade removed from his Motown‑revival debut, the French crooner turns inward, writing about millennial ennui, therapy sessions, and the cost of perpetual optimism. Producer duo Danny Van’t Hoff and Bastien Cabezon give him dusty break‑beats, phased guitars, and Rhodes chords that blur classic soul with the lo‑fi hip‑hop playlists that soundtrack today’s Paris cafés. Hooks remain Ben’s super‑power as “I GØT HOME” rides a four‑bar whistle line you’ll hum all week, while “IM GØØD” recruits Adi Oasis for a slippery bass‑lead duet that recalls Sly & Robbie’s dub‑soul projects. Underneath the charm, the songwriter wrestles with burnout—“HARD TO DØ” places gospel organs under lyrics about permitting yourself to quit. Ben calls the record his “most personal” statement, a diary of “balancing old and new.” It plays that way: vintage warmth, yes, but filtered through frank 2025 vulnerability. — Randy

Melanie Fiona, Say Yes (EP)

Melanie Fiona’s first multi‑song release in more than a decade doubles as a soft reboot for the once‑major‑label singer who spent years recovering from vocal cord trauma. In recent interviews, she frames Say Yes as “a permission slip to reclaim joy” while steering her own indie imprint, LoveLinc Music. The suite opens with the gospel‑leaning title track, anchored by plush Rhodes chords and a call‑and‑response hook that invites literal audience participation. From there, she toggles between buttery mid‑tempos (“Make Me Feel” featuring Vallejo rapper‑poet LaRussell) and a sumptuous closing jam that sneaks in bass licks from Thundercat and drum programming from Andre “Dre” Harris—effectively stitching her ‘00s neo‑soul heyday to the present. The EP’s real power, though, lies in Fiona’s willingness to narrate survival: she threads verses about postpartum anxiety and industry disillusionment through melodies that refuse to mope, giving the record an affirming pulse reminiscent of The MF Life but lighter on its feet. It’s an easy front‑to‑back spin that reminds you vocal texture can carry autobiography. — Jamila W.

duendita, A Strong Desire to Survive

Queens vocalist-producer duendita distills trauma, healing and righteous anger into a ten-song set. Field-recorded subway rumbles and detuned upright-piano chords underpin opener “Why I Didn’t Report,” where her caramel alto floats above clipped news-broadcast samples to confront assault silence culture. Throughout, she toggles between choral stack-ups worthy of Renaissance polyphony and skeletal piano ballads like “Baby Teeth,” recorded in her bedroom with a single Zoom mic. She self-produces most tracks, but MIKE slips in lo-fi drum palettes on “HTP,” echoing their New York DIY lineage. The album’s sequencing feels nonlinear—short interludes bleed into full-length songs, mirroring the circular nature of recovery. By the closing voicemail collage “All Mine — June 11, 2019,” she reframes survival not as a destination but perpetual motion, each track a checkpoint in reclaiming bodily autonomy. — Jamila W.

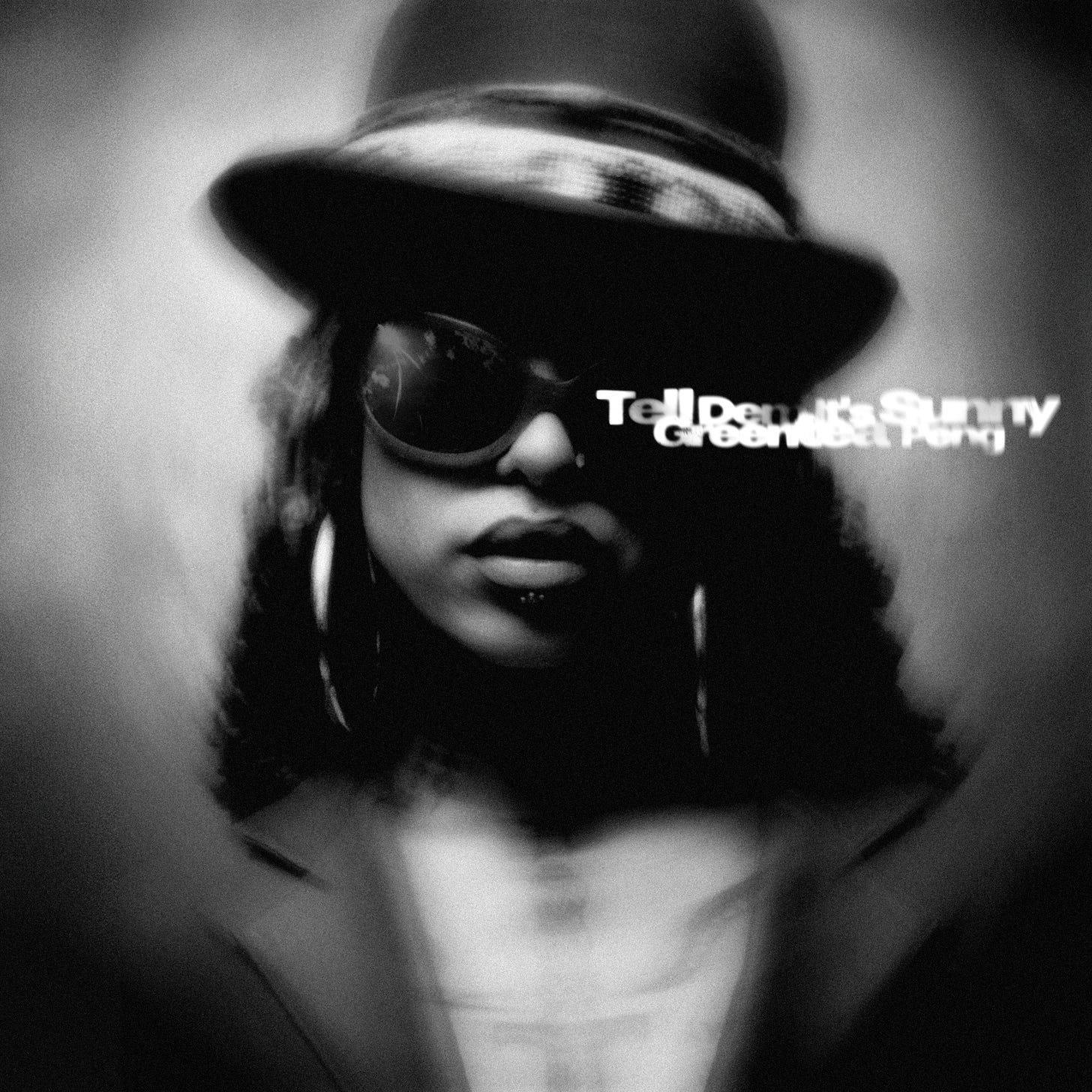

Greentea Peng, Tell Dem It’s Sunny

Recorded largely in 432 Hz, Peng’s sophomore LP feels like sun-drenched street gospel sung through a kaleidoscope. “Tardis (Hardest)” drapes her husky contralto over a strutting dub bass-line and skittering rim-shots, the song’s time-travel metaphor doubling as an invitation to detach from linear thinking and sink into groove. “My Neck,” co-produced by South London experimentalist Wu-Lu, folds lo-fi hip-hop drums into flanged guitar echoes, bridging the earthy and the astral without resorting to New-Age vagueness. Even quieter pieces such as “Raw,” built on finger-picked acoustic chords and barely there upright-bass—carry gentle psychedelic swirl in the background, suggesting that clarity and cloud-haze can coexist. Peng writes in mantra-length phrases, often repeating lines until they loosen their semantic grip and become breath themselves; the effect is meditative but never sleepy, because the rhythm section keeps feet tethered to pavement even as minds arc toward cosmos. If her debut chronicled inner turbulence, Tell Dem It’s Sunny is the exhale after the storm: not naïve bliss, but cultivated brightness that accepts shadow as teacher. — Jamila W.

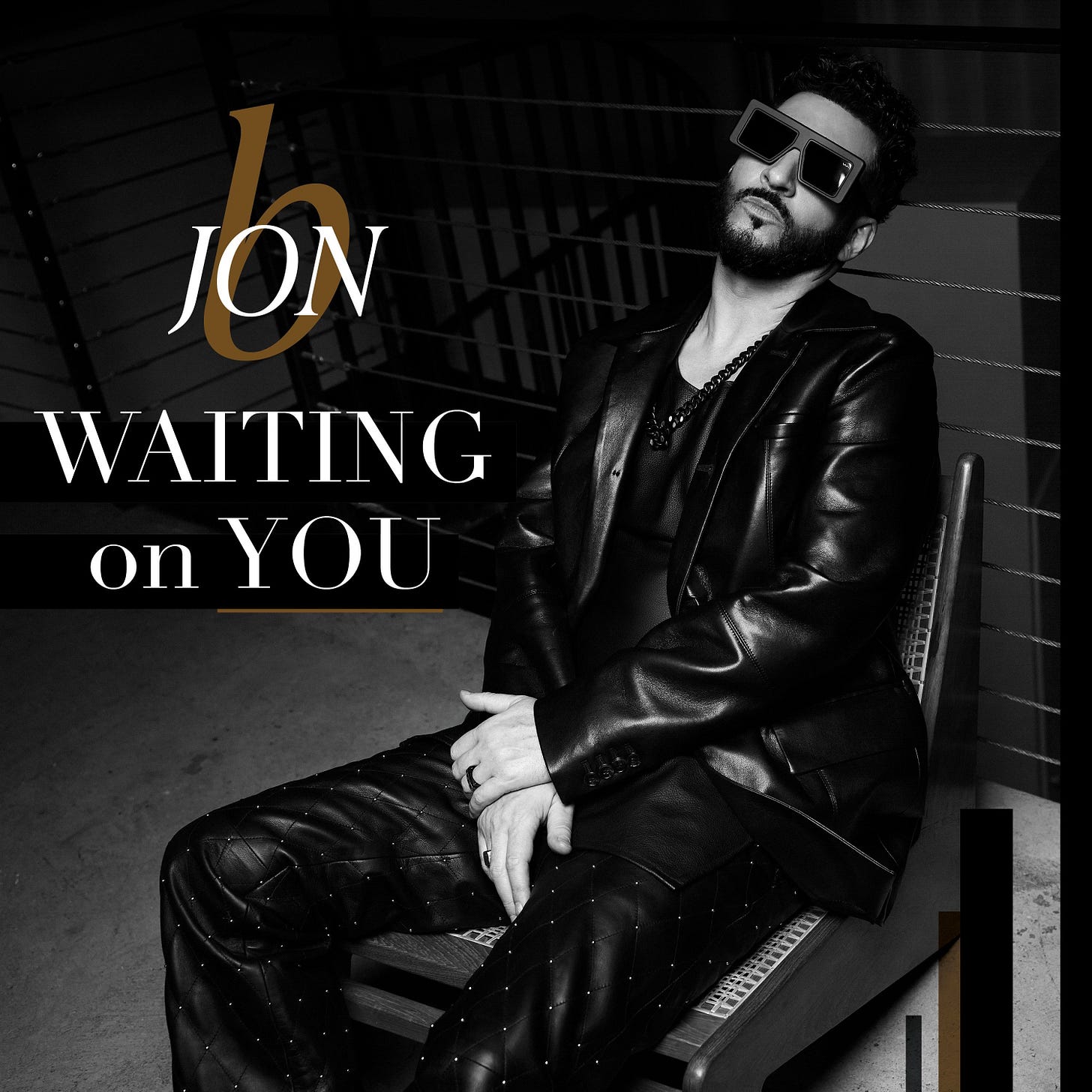

Jon B, Waiting On You

Jon B returns after more than a decade with an album that sounds like a seasoned songwriter revisiting his ‘90s blue-eyed-soul blueprint but sanding off the youthful bravado. The title track, a duet with Tank, glides on a finger-picked guitar loop and rim-click drums, its hook expanding into radiant stacked harmonies that nod to Donny Hathaway without feeling retro. He leans heavily on live instrumentation: “Still Got Love” rides a rolled-off-hi-hat groove reminiscent of “They Don’t Know,” yet the chord changes are richer, letting his tenor linger around suspended ninths before resolving into velvet cadences. Jon’s pen stays understated; on “Natural Drug,” he sketches intimacy as euphoric addiction, his falsetto flipping into chest voice just as the Rhodes vamp modulates up a half-step—a subtle signal of desire escalating. Alex Isley’s cameo on “Show Me” introduces a feathery counterpoint: her airy harmonies float over brushed snares while Jon lays down guttural ad-libs, framing the duet as a soft-loud dialog rather than a simple trade-off. Waiting On You never chases trends; instead, it updates Jon B’s classic palette with deeper harmonic pockets and lyrics steeped in grown-folks patience. — Tai Lawson

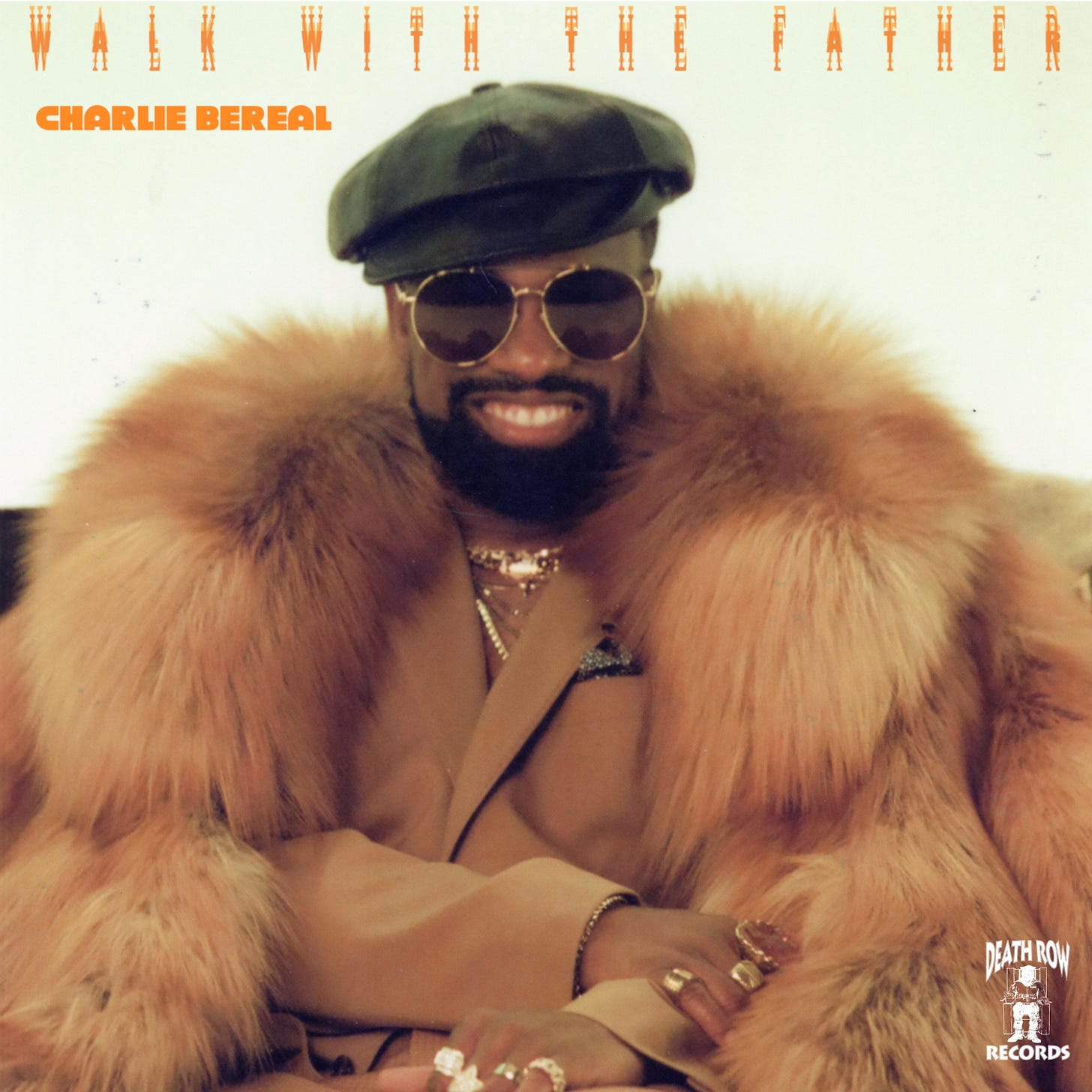

Charlie Bereal, Walk With the Father

Guitarist-turned-front-man Charlie Bereal filters gospel conviction through Los Angeles’s low-rider soul lineage. “Hope,” the opener, braids warm Wurlitzer chords with talk-box filigrees, as Bereal’s tenor pleads for mercy over a pocket that swings like Willie Mitchell’s house band chauffeuring a G-funk rhythm track. Mid-album highlight “The Greatest,” featuring a smoked-out cameo from Snoop Dogg, flips the Isaac Hayes-style symphonic intro trope on its head: lush strings give way to rubbery bass, and Snoop’s baritone drawl slips into Bereal’s bluesy vibrato like dusk sliding into night. “Never Gonna Take Away My Love” squares four-part stacked harmony against clipped funk guitar, nodding to the gospel quartet tradition while stitching in modern modal chord substitutions that keep the progression fresh. The title track slows the tempo to heart-beat pace; a lone organ swell underpins lyrics framing faith as everyday walk rather than mountaintop epiphany, capping an album that treats devotion less as sermon and more as late-night conversation on a city stoop. — Brandon O’Sullivan

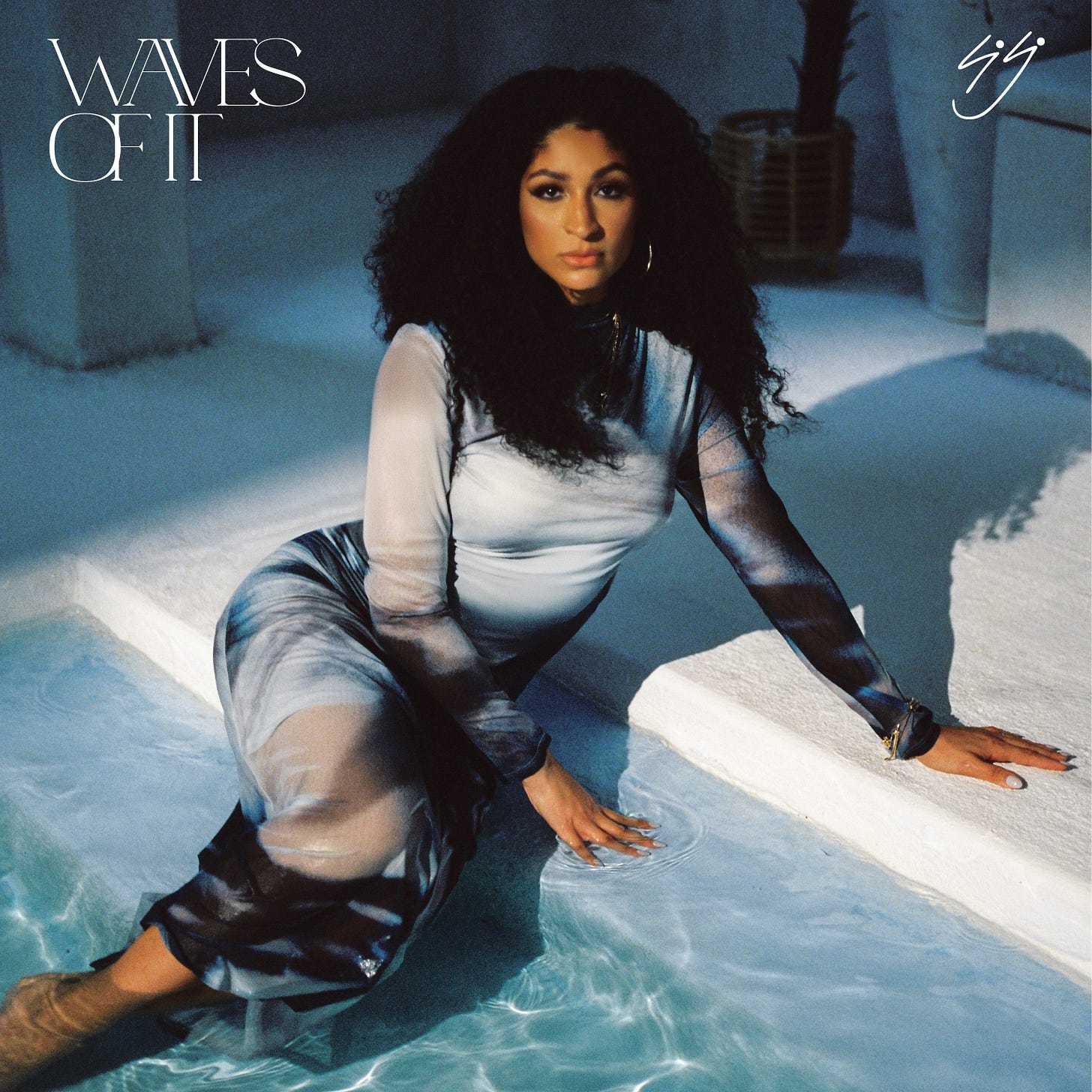

GIGI, Waves of It (EP)

Detroit‑born newcomer GiGi (not to be confused with the NYC indie rocker Gigi Perez) parcels five songs into a 15‑minute mood‑board that toggles between airy R&B and gauzy bedroom‑pop. This project centers on the ebb‑and‑flow metaphor of its title: love rushes in, retreats, and rushes back stronger. “Tidal Wave” rides brushed snares and humid Rhodes to document that breath‑catch moment when you realize a crush has depth; “Reacquainted” flips nylon‑string guitar and chopped vocal clips into a lo‑fi confessional about rekindling trust. GiGi’s vocal phrasing nods to early Brandy—velvet glide with hiccuped runs—while her lyric sheet leans diaristic: lines about voicemail drafts, chipped nail polish, and secondhand novels. — Brandon O’Sullivan

ROSEYE, Ways of Speaking (EP)

ROSEYE floats across five tracks of satin synth pads, finger-snap percussion, and sax lines courtesy of Candy Dulfer that ripple like heat mirages. “Ayesha” opens with layered vocal stacks that swell into a mid-tempo stepper, while “Deep Dive” invites its lover into aquatic metaphors over sub-bass pulses that bloom like underwater thunder. Throughout, lead vocalist Tallulah Rose slips between English and wordless melisma, turning every hook into an exercise in emotional code-switching. Ways of Speaking balances sensuality with self-interrogation. “Y.A.M.U” reframes vulnerability as power, chanting “You are my undoing/You will be my ruin” until surrender sounds victorious. Subtle polyrhythms draw on broken-beat and Afro-Latin grooves, but the mixes stay air-light, letting Rose’s phrasing ride just ahead of the pocket. In barely twenty minutes, the group sketches a world where intimacy becomes its own language, a reminder that sometimes the most radical statement is speaking softly yet clearly about desire. — Harry Brown

Alex Isley, When (EP)

Alex Isley’s six-song suite moves with the hush of late-night conversation, every element placed to leave negative space that feels as expressive as any note. “Hands” opens on a half-time kick-snare that Camper dresses in rim-shot echo; Isley’s lead glides above, shadowed by a doubled octave that slips in and out like breath, underscoring lyrics about consent and tenderness. KAYTRANADA’s production on “Mic On” loosens the EP’s whispery aesthetic just enough, flipping a chopped vocal sample into syncopated stabs that let Isley shift into a rhythmic sing-rap cadence—proof she can flex without breaking the project’s intimate aura. She pairs a liquid bass run with brushed-steel hi-hats, and Isley sprinkles sly, conversational asides (“You ain’t check the bloodline?”) that transform self-affirmation into playful flirtation. “Thank You for a Lovely Time” dissolves lead and background into one shimmering chord cluster, as if signing off by folding herself back into the sonic ether she commands so effortlessly. — Tai Lawson

Coco Jones, Why Not More?

Coco Jones scales up from breakout EP to full-length with a record that moves like a big-budget romance film where wide stylistic shots, tight emotional close-ups, and a clear through-line of self-possession. The title track taps YG Marley for a syncopated reggae swing, but Jones centers her honeyed alto, flipping from melismatic runs to clipped patter as she questions why mutual devotion ever needs justification. “Taste” flips the iconic “Toxic” acapella into a stop-start trap pattern; rather than coasting on nostalgia, Jones re-pitches the riff into a minor key and sings against it, turning a familiar melody unsettling and seductive at once. Coco toggles between lush, late-’90s vocal stacking (“Here We Go (Uh Oh)”) and sleek, atmospheric Pop&B (“By Myself”), but the production (handled by Stargate, London On Da Track, and Jasper Harris) never overwhelms her phrasing. Instead, she uses each beat to show new facets: a scratch in the voice on a climactic high note, a whispered ad-lib tucked behind the three-and-one. Coco Jones is proving she can inhabit any R&B landscape without losing the tactile warmth that made “ICU” a breakout moment. — Tai Lawson