The Best Rap Music of 2025 (So Far…)

This six-month scoreboard for mainstream rap is a death sentence for the majors, but indie rap has done what is supposed to do at its best: grow new language, new pockets, and new myths in real time.

Rap’s 2025 scorecard so far looks like a split-screen. At the top of the charts, major-label campaigns continue to push bigger rollouts, yet they yield forgettable music, while just below the surface, a fleet of self-directed projects is thriving on craft, community, and Bandcamp Fridays. A chorus of fans is already calling this the weakest commercial half-year in recent memory, pointing to a run of marquee releases that generated plenty of chatter and TikTok challenges but little replay value.

Mainstream fatigue is easy to hear. Playboi Carti tried the opposite tactic, unloading a 30-track slab of “void rap” simply titled Music—a maximalist gesture so diffuse that its fragments rarely land with intent. Joey Bada$$ even manufactured a coast-to-coast dust-up with his New Year’s salvo “The Ruler’s Back,” using stray disses, leading to a full-out West Coast back-and-forth (specifically Daylyt and Ray Vaughn), to score headlines rather than honing a cohesive record. Across the board, allegedly surefire singles (collabs, viral-dance hooks, deluxe-edition filler) are missing their marks often enough to merit YouTube autopsies titled “Every Single That Flopped in 2025 (So Far).” Even undeniable streaming wins, like Central Cee’s Can’t Rush Greatness breaking first-day Spotify records, come wrapped in a risk-averse formula rather than a fresh perspective. And do you remember Lil Baby released an album this year? Exactly, it’s forgettable and the music sucks.

By contrast, the independent lane sounds liberated (SPOILER). As we pivot into mid-year round-ups, the most compelling rap stories aren’t the forced “moments,” but the slow-burn arcs. The following list of 2025’s best rap records, and the context they create, belongs to that underground groundswell; the majors will have to catch up or keep chasing engagement metrics in a room that’s stopped listening.

doseone & Steel Tipped Dove, All Portrait, No Chorus

The title is literal. Across a sprint of fourteen miniatures, doseone refuses to settle into hooks, instead firing off knotty couplets that twist, rewind, and splinter before any comfort can set in. Steel Tipped Dove meets that restless energy with production that ricochets between dust-covered breakbeats, abrupt tape stops, and pockets of negative space; the beat change inside “Went Off” feels like a floor collapsing beneath your feet, only for a warped vocal sample to catch the fall. Throughout, doseone keeps one foot in the abstract and one in the tangible: “Scales Sway” spirals through surreal imagery—he compares his flow to a “python” uncoiling—yet lands on an eerily plainspoken refrain, the voice suddenly naked in the mix. Cameo verses (Open Mike Eagle, billy woods, Myka 9) don’t break the spell; they feel drafted into doseone’s private language, volleying syllable games rather than chasing spotlight moments. The result is a record that feels like a sketch-book filled at manic speed—pages torn out, ink still wet, imagination outrunning the metronome.— Phil

Queen Herawin, Awaken the Sleeping Giant

Herawin frames the album as “a musical memoir…about awakening to your inherent power,” and the record moves like a cycle of self-interrogation. On “Anxiety” she chants, “I got anxiety, it really sucks/I meditate to not erupt,” looping the mantra until the drums themselves seem to be exhaling with her. That vulnerability never dilutes her edge; when Breeze Brewin answers back on “Gluttony,” the siblings’ voices tumble over Neff Beatz’s low-end throb in a flex that is half confession, half battle-rap. Moments of calm arrive when Open Mike Eagle bends his tenor around her double-time cadences on “Shame,” offering weary counter-melody before Herawin barrels back in with verse-length run-on sentences that recall her formative Bronx park-rap sessions. The album’s refusal to moralize—each sin examined but never neatly resolved—feels closer to diary pages than to sermon, leaving the listener in that uneasy dawn where resolve and relapse coexist. Early reception from independent rap circles has praised this nakedness, calling the LP “a vulnerable musical memoir” and “special in how it hits every aspect.” — Brandon O’Sullivan

Pink Siifu, Black’!Antique

Siifu’s latest canvas is massive, featuring nineteen tracks that blend glitch, gospel, trunk-rattle bass, noisy punk interludes, and chopped-and-screwed radio static, sequenced like a pirate-signal variety show. He jumps voice-boxes at will: high-pitched croons melt into barked ad-libs, then retreat into woozy whispers that sound recorded across the room. That shape-shifting is thematic: opener “BLACK’!ANTIQUE’!” welds Memphis-style 808 thumps to a swirl of flutes while Siifu narrates diasporic time-travel (“I been here/I been gone/I been back”) as if memory itself is buffering. Mid-album peak “1:1[FKDUP.BEZEL]” drapes Bbymutha’s drawl over a queasy Rhodes loop, turning a flex verse into a séance for Southern rap lineages. Even the shortest sketches carry narrative heft: the 92-second “OUTSIDE’!” crams police-scanner chatter, distorted jazz chords, and Siifu muttering “tryna breathe” until the tape snaps. Across the sprawl he renders oppression, joy, grief, and celebration as overlapping radio frequencies—sometimes they harmonize, more often they fight for bandwidth. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Aesop Rock, Black Hole Superette

Aesop Rock takes sole control of the beats, stitching tight drum grids to clipped keyboard hooks and placing speech samples where most rappers would drop ad-libs. “Secret Knock” introduces a habit of pairing everyday details—door codes, loyalty cards—with broad questions about routine and privacy, while “1010WINS” lowers the percussion so Armand Hammer can volley terse headlines that emphasize information overload. The melodic outline stays clear even when synth layers multiply, which lets Aesop’s dense word clusters remain intelligible without resorting to obvious hooks. “Checkers” pivots on a piano stab that cuts against a shortwave-radio squall, and “Snail Zero” turns a loose bass line into the backdrop for wry observations about slow growth. Open Mike Eagle slips into “So Be It,” delivering a dry counterpoint that matches the album’s understated tone. A short run of instrumentals midway through provides breathing room, each built from a single motif that fades before it overstays. Throughout the hour-plus runtime, city sounds and consumer chatter never feel tacked on; they serve as reference points that keep the more abstract lines grounded. — Harry Brown

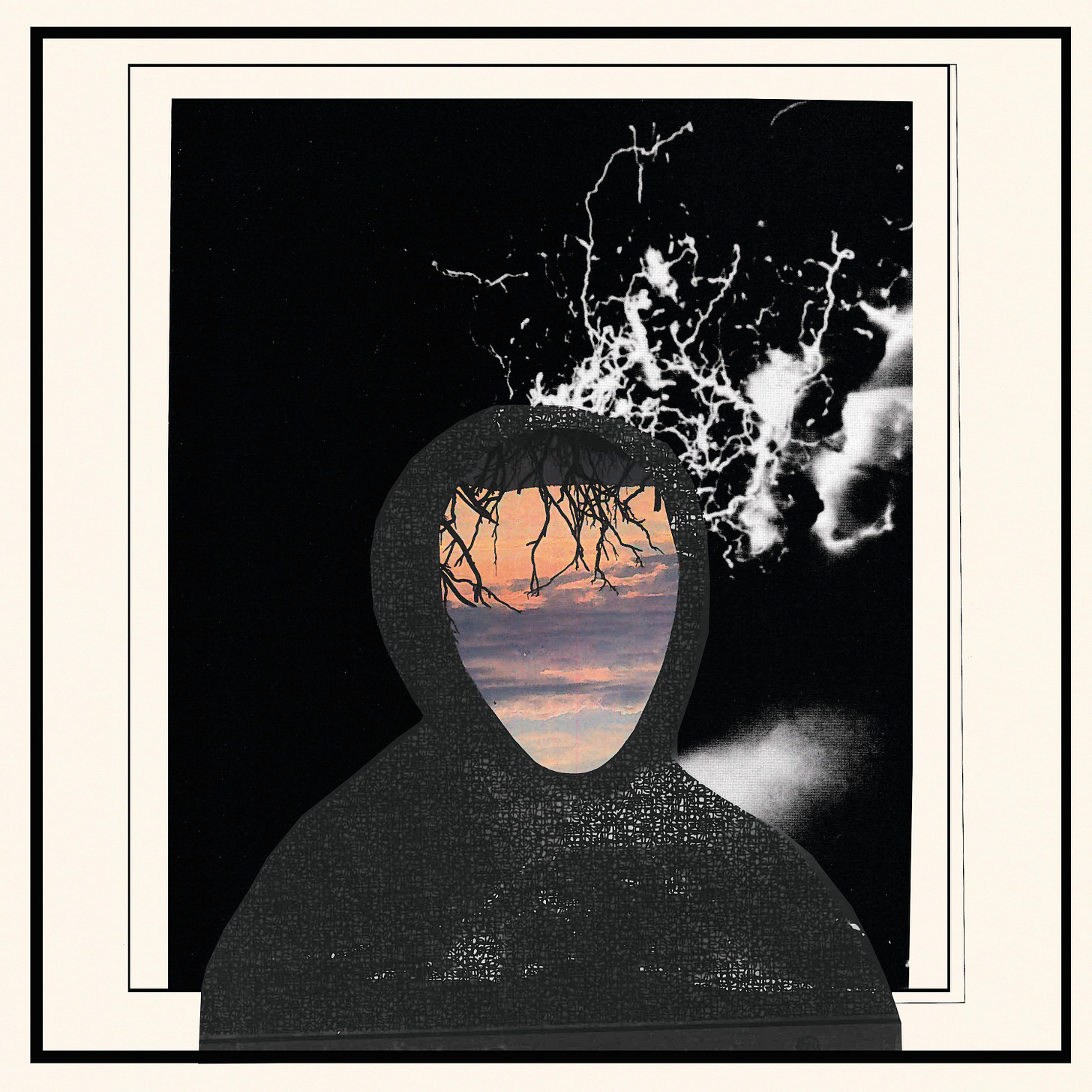

Miles Cooke, Ceci N’est Pas un Portrait

Cooke titles his record after Magritte’s famous non-pipe, an apt wink for music obsessed with perception and misdirection. The emcee spits in long, breathless torrents that recall Def Jux-era word density, yet the beats are spare: upright-bass loops, muffled kick drums, brief piano stabs, all leaving oxygen for his syllable mazes. On “negus,” he starts in anxious near-whisper—“I could’ve sworn I heard fate whisper, then along came the pressure”—and gradually escalates to a gritted-teeth roar, mirroring a panic attack cresting and crashing. “The Book of Job Part II” frames survivor’s guilt in biblical language, Cooke flipping scripture into sucker-punch gallows humor—“brief leisure edit life to cue the applause break”—over a woozy Rhodes vamp. His chess-metaphor duet with Defcee, “Zugzwang,” snakes through internal-rhyme coils so tight they feel almost claustrophobic until the hook erupts in shouted gang vocals, a rare communal exhale. — Harry Brown

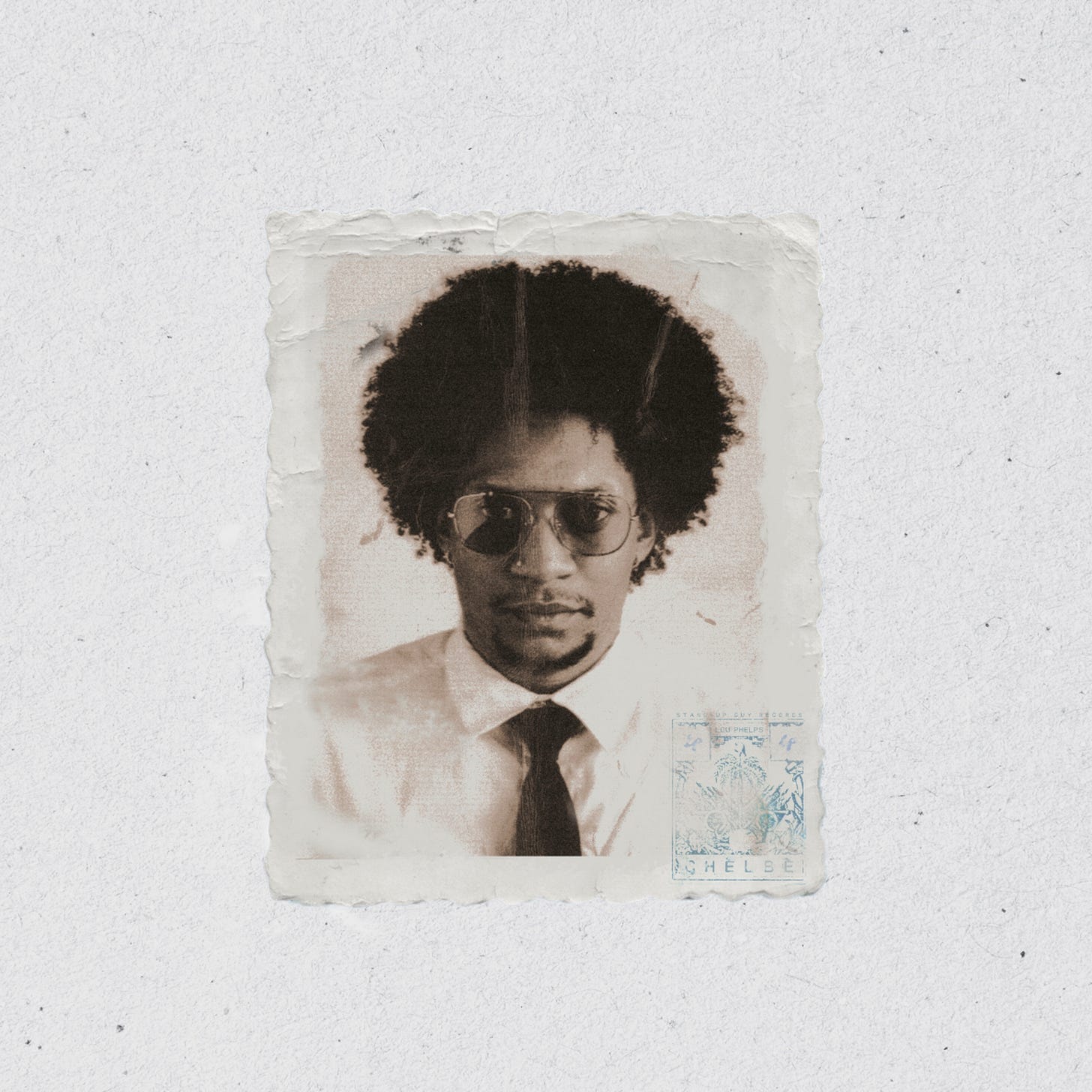

Lou Phelps, Chèlbè

The Creole title translates loosely to “fly,” and the record carries itself accordingly. Spring-loaded drums pop like bubble wrap under KAYTRANADA’s warped synth-bass, while Lou switches from English to French to Haitian Creole without warning. “Prolly Us” is a neon-lit flirtation built on kick-drum syncopation that never quite lands on the down-beat, mirroring the song’s teasing hook. He rides the liquid-funk of “2AM” in a tone pitched halfway between Pharrell’s airy sweetness and early-2000s Clipse braggadocio. Elsewhere, “AftaParty” drapes palm-wine guitar over a pulsating four-on-the-floor pulse, making the after-hours feel wider than the dance floor that preceded it. What knits the set together is swagger touched by vulnerability: even at his most playful, Lou slips in coded notes about immigrant perseverance and Montréal’s bilingual hustle, proving party music can still carry memoir weight — Phil

clipping., Dead Channel Sky

The trio opens with fifty-one seconds of electronic hiss and detuned radio chatter, a prelude that feels like someone hand-scanning an abandoned satellite band for signs of life. “Dominator” answers the call; Daveed Diggs raps in clipped bursts synced to distorted drum-and-bass hits, sketching an unnamed protagonist who hacks power grids “with synaptic wire and borrowed rage,” a line delivered so quickly it feels typed rather than spoken. The song bleeds into “Change the Channel,” where a saw-toothed synth riff cuts in and out like an emergency broadcast, invoking the thrill and terror of living inside a perpetual signal. Diggs rarely claims an “I,” instead voicing avatars caught in capitalism’s circuitry. A nightclub gatekeeper who sneers, “God is not here, he forgot to rock his mirrorshades,” a shell-shocked code-slinger coaxed into a mercenary gig with the promise of eternal cloud storage. The collisions between these stories create a widening paranoia, each of them hints that private histories are forever one data breach away from public ruin. — Harry Brown

PremRock, Did You Enjoy Your Time Here...?

The title’s polite question hangs over every bar, turning each anecdote into a border crossing between nostalgia and existential dread. “Angel’s Share” sets the tone with a horn-flecked loop that staggers like jet-lagged footsteps; PremRock locks into its lurch, musing on airports and AA pamphlets before dryly admitting, “I collect layovers like postcards nobody asked for.” His delivery lands somewhere between deadpan stand-up and late-night confessional, letting punch lines and revelations share the same breath. Controller 7, Blockhead, and Sebb Bash supply beats that feel gently unsettled, lo-fi textures, chords that detune by micro-cents, kicks that arrive a hair ahead of the snare, mirroring the record’s thematic liminality without drowning it in production fireworks. When billy woods turns up on “Receipts,” the mood darkens; his verse rummages through “unpaid invoices of the soul” while a muted trumpet coughs in the background. — Phil

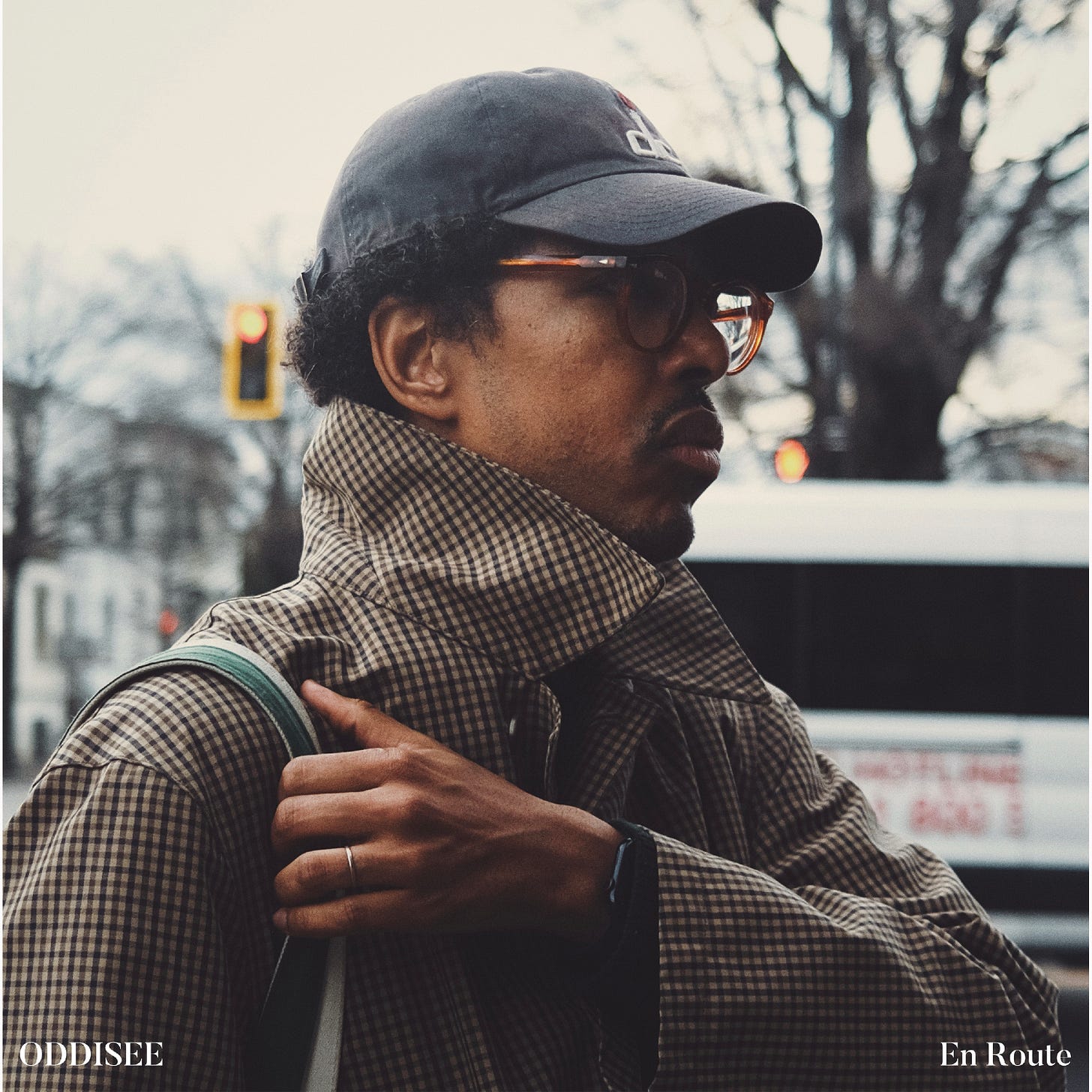

Oddisee, En Route (EP)

Across four lean tracks, Oddisee distills his gift for travelogue rap into a brisk eleven-minute sprint that still feels unhurried. The writing revolves around motion: missed boarding calls, mental detours, spiritual layovers, where each idea is carried in compact phrases that mirror the EP’s economy. “Tomorrow Can’t Be Borrowed” sets the tone, folding a gentle warning about procrastination into a near-danceable groove. By “Small Talk,” the focus shifts to interpersonal drift, questioning whether casual conversation can keep pace with personal growth. Oddisee’s own mix balances clarity and warmth, letting the backbeat breathe so every syllable lands crisp. Even at such brevity, “Natural Selection” circles back to the opening riff in half-time, implying that every journey is a loop waiting to restart. — Harry Brown

Chuck D, Enemy Radio: Radio Armageddon

Chuck D wields his baritone the way Coltrane used sheets of sound—layered, unrelenting, and always aimed at a higher civic purpose. Over breakbeats that crunch like smashed radios and shards of distorted acid-rock guitar, he re-stacks the Bomb Squad’s collage aesthetic into a leaner but no less combustible broadcast that ricochets between scowling funk riffs and proto-punk thrash. Cuts such as “Black Don’t Tread” and “Rogue Runnin’” bolt scratch choruses to thrumming bass, framing verses that rage against algorithmic misinformation and voter suppression with the same urgency he once leveled at Reagan-era racism. Yet the record is hardly a nostalgia trip: on “New Gens,” he cedes the spotlight to Stetsasonic’s Daddy-O and a chorus of younger MCs, threading old-school mic-command into a rolling drill-adjacent cadence that argues cross-generational solidarity is the new radical gesture. Across the album’s “station breaks,” hard-panned sirens, Black radio idents, and shortwave static create the illusion you’re spinning a dial through the apocalypse—only to land, again and again, on a voice that refuses to yield. — Phil

LIBRA, Everyone’s First Breath

LIBRA sets the scene, alternating between mid-tempo soul progressions and crisp rap cadences, using each pivot to underscore the tension between fragility and resolve. When low-end 808s break through on “Spells,” their sudden heft lands because earlier passages had withheld that punch, turning dynamic contrast into a guiding principle rather than a gimmick. A loose reinterpretation of “Nikes On My Feet” shifts the familiar hook onto shimmering Rhodes chords and distant handclaps, signaling the project’s intent to reshape nostalgia rather than chase it. Woodblock clicks and finger snaps sit high in the mix, providing a subtle pulse through slower stretches that might otherwise drift. The cumulative effect is intimate without being confessional, inviting repeat listens to catch the quiet shifts in mood. — Randy

Black Milk & Fat Ray, Food from the Gods

When these longtime Detroit conspirators reunite, the chemistry is immediate: Black Milk’s drums slap with MPC grit but pivot mid-bar into Fender-Rhodes sorcery, while Fat Ray’s baritone slides between hustler parables and mystical asides like a griot who’s read too many sci-fi paperbacks. “Elderberry” filters Detroit’s herbalist folklore through drum fills that ricochet like loose car parts on I-94; Ray brags about plant-based immunity while Milk doubles the snares until they splinter. Danny Brown’s manic squeal on “Just Say No” cracks the album’s granite surface long enough for a laugh before the beat slams shut again, while Guilty Simpson and Bruiser Wolf remind listeners that Detroit storytelling can swing from menace to slapstick in a single bar. Throughout, Milk’s arrangements lean on minor-key Rhodes and blaring horns, evoking his own Dilla tutelage without slipping into pastiche; “Talcum,” with its all-rim-shot funk and bass-guitar stabs, shows how he can still make a three-minute loop feel like a short film. Ray matches that cinematic scope by veering between street reminiscence (“stashing in the walls like Jerome”) and metaphysical detours (“spirits in the griot”), delivered in cadences that drag consonants the way a carpenter drags nails across wood. For all its bluster, the record never bloats; most songs hover around two-and-a-half minutes, a discipline that turns every hook into a coliseum chant and every beat switch into a jolt. — Harry Brown

Blu & August Fanon, Forty

Producer August Fanon gifts Blu a kaleidoscope of soul fragments, detuned Rhodes chords, dusty swing drums, woozy flute runs, and Blu answers with verses that treat aging like an open-mic testimony: honest, cracked, unafraid to laugh at itself. The sequencing is clever: “Forty” sets the tone with jubilant horn stabs, then a relay of underground luminaries (Mickey Factz, Charles Hamilton, R.A.P. Ferreira) file in, each handed a beat that skitters between boom-bap minimalism and kaleidoscopic jazz loops. Every hook reconfigures the LP’s central mantra—worth is measured in wisdom, not timeline metrics. Mid-album, “Love (1-4)” runs nearly eight minutes, fluttering through four pocket-grooves while female vocalists stack harmonies like 1970s Roy Ayers sessions; by contrast, “Bible” cuts to a two-minute sermon over funereal organ. The quick pivots mirror turning pages of a photo album: snapshots of fatherhood, youthful missteps, spiritual doubt. Blu never hides the scuffs in his flow, but Fanon’s crate-digger textures wrap each confession in warmth, making the record feel less like nostalgia and more like a living scrapbook still being written. — Harry Brown

Saba & No ID, From the Private Collection of Saba and No ID

Saba’s partnership with Chicago elder No ID yields a record that feels handwritten in the margins of family photo albums—snapshots curled at the edges, annotated in fountain-pen blue, passed down with stories half-true because they need to be. “Every Painting Has a Price” sets the thematic stakes. Saba warns, “What if it drove us out our minds? I guess every painting has a price,” equating creative obsession with auction-block extraction. No ID’s sample of Mountain’s “Long Red” —filtered drums, grainy crowd noise—acts less as a nostalgic wink than as a reminder that Black cultural labor is forever collaged from fragments of older stories. Elsewhere, Saba toggles between playful intimacy and durable grief, where one verse jokes about dating apps, the next wrestles with the unpayable cost of inherited trauma, yet the pivot feels natural because community lore holds both jokes and elegies in the same breath. — Phil

billy woods, Golliwog

When Golliwog opens with “Jumpscare” with warped horns and tape hiss, it sets a claustrophobic mood that never fully lifts. billy woods raps in dense, imagistic bursts, stacking references to colonial history, horror cinema, and everyday micro‑aggressions until the lines feel like overlapping newspaper clippings. Throughout the album, the production pivots between dusty jazz loops and abstract sound design. “Star87” floats over a detuned vibraphone riff that keeps slipping out of key, while “Misery” uses a brittle guitar figure that fractures under heavy reverb. Guest spots amplify the kaleidoscope; Bruiser Wolf’s off‑kilter drawl on “BLK Xmas” adds sardonic humor, Despot’s surgical precision on “Corinthians” sharpens the track’s edges, and ELUCID appears multiple times, his voice acting as both mirror and foil to woods’ weary baritone. The middle stretch (“Waterproof Mascara,” “Counterclockwise,” “Pitchforks & Halos”) digs into paranoia, with drums that drop out unexpectedly, forcing the listener to cling to woods’ internal rhythms for footing. Near the end, “Lead Paint Test” and “Dislocated” widen the sonic palette with industrial clangs and ghost‑choir samples, pushing the project into near‑apocalyptic territory. Despite the heavy subject matter, there is a sly playfulness in woods’ rhyme schemes; multisyllabic patterns tumble into sudden blunt phrases, mirroring the album’s thematic tension between performance and painful memory. — Phil

Ray Vaughn, The Good, The Bad & The Dollar Menu

Top Dawg Entertainment’s Long Beach wildcard turns the fast-food metaphor into autobiography—a mixtape-length origin story. Built on crate-dust loops and sparse West-Coast bass, the tape hops from hunger-pangs one-liners (“make ’em McDouble back”) to reflections on policing, rivalries, and surviving price-tag rap economics. Vaughn’s flow keeps switching gears—triple-time snaps on “XXXL Tee,” half-sung cadences on “Flocker’s Remorse”—mirroring the album’s tug-of-war between braggadocio and survivor’s guilt. He punctuates verses with region-specific slang (“Shasta flats,” “K-town runs”) that place listeners on the 405 after midnight without tourist framing. At its emotional peak, he pairs with artists like Gemaine’s gospel-soaked hook on the aforementioned track with Vaughn confessing, “Mama taught me prayer hands, I turned them to a lockpick,” a line that freezes the rapper mid-transformation. By resisting moralizing and refusing to glorify the hustle, Vaughn renders a coming-of-age that feels both local and archetypal. — Nehemiah

Ghais Guevara, Goyard Ibn Said

Structured in two acts, Guevara’s concept piece follows a fictional anti-hero who rises from corner rap star to luxury-brand demigod before watching the spoils curdle. Act I’s centerpiece “The Old Guard Is Dead” pairs roiling trap drum-programming with a compressed soul sample that sounds like vinyl spun backwards; Guevara rips through double-time boasts only to undercut them with “Aim for the moon, rose from the gallows”—a couplet that frames triumph as execution by another name. Act II flips the palette: “Leprosy” slows the tempo, substituting hazy guitar chops while he sneers, “actions don’t match their lyrics,” a self-indictment as much as industry critique. Throughout, his flows dart between Philly street punchlines and West African griot cadence, a nod to the historical Ibn Said, whose name he borrows. By finale “I Gazed Upon the Trap with Ambition,” the beats have thinned to skeletal clicks, and Guevara’s voice fractures into half-sung laments, the anti-hero finally staring into luxury’s hollow center. The narrative gambit never feels forced because Guevara’s technical fireworks—polysyllabic rhyme chains, sudden meter shifts—keep the story wired to the adrenal rush of outstanding rap records. — Brandon O’Sullivan

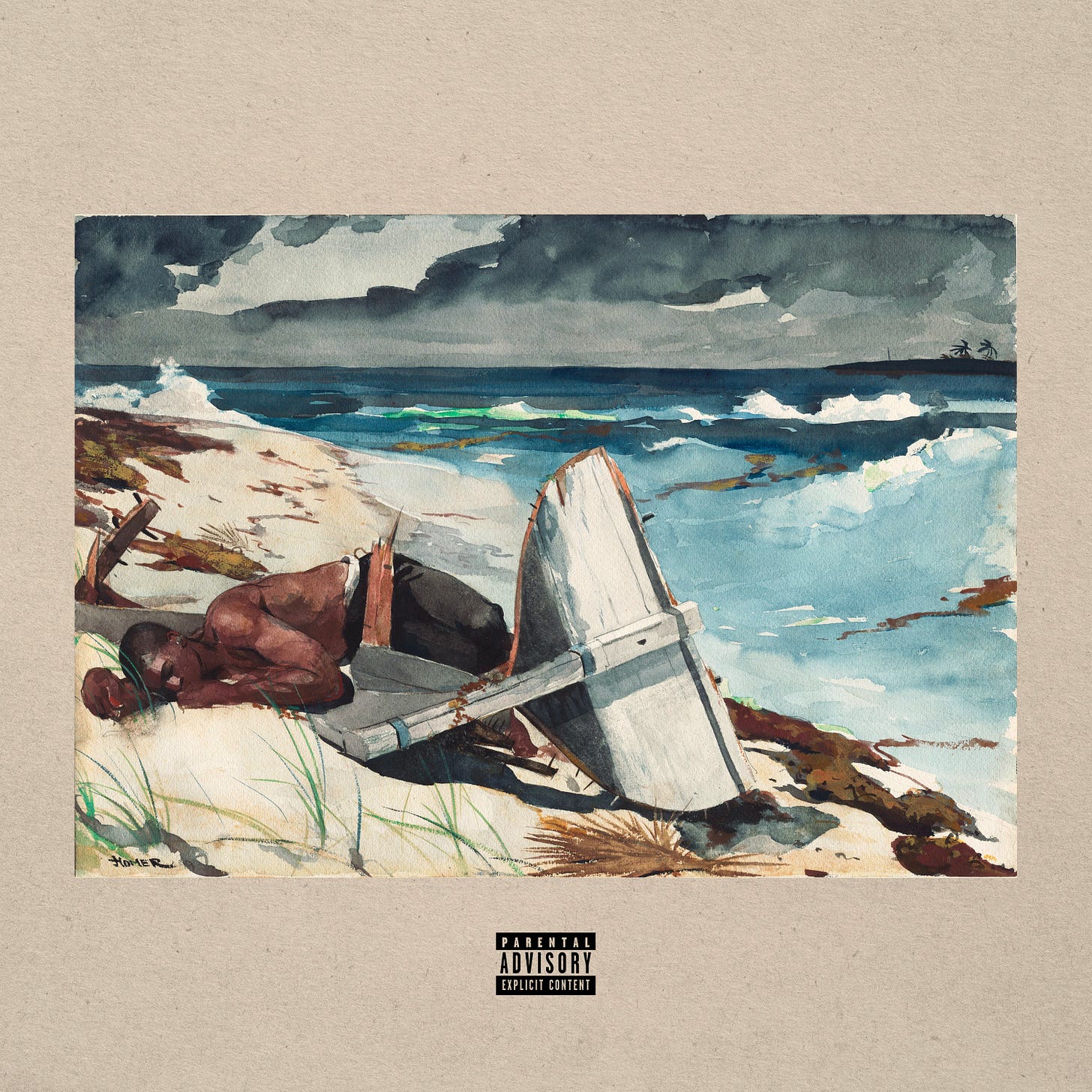

Wretch 32, Home?

Wretch’s writing has always balanced nimble wordplay with confessional heft, but here the stakes feel existential. The opening track juxtaposes news-clip sirens with a choir that could have drifted in from Brixton’s Pentecostal churches, underscoring his question: Can a nation that polices your very breath ever be “home”? Over minimalist, hi-hat-heavy production, he threads Jamaican patois into North London argot, treating language itself as a contested post-colonial terrain. Mid-album standout “Diaspora Dinner” samples clinking cutlery and dub bass, turning the simple act of sharing food into a metaphor for generational memory. The project ends not with resolution but with a question-mark bass-drum thud, Wretch whispering, “Maybe I’ll find it in my son’s accent,” a line that lingers long after the music fades. — Ameenah Laquita

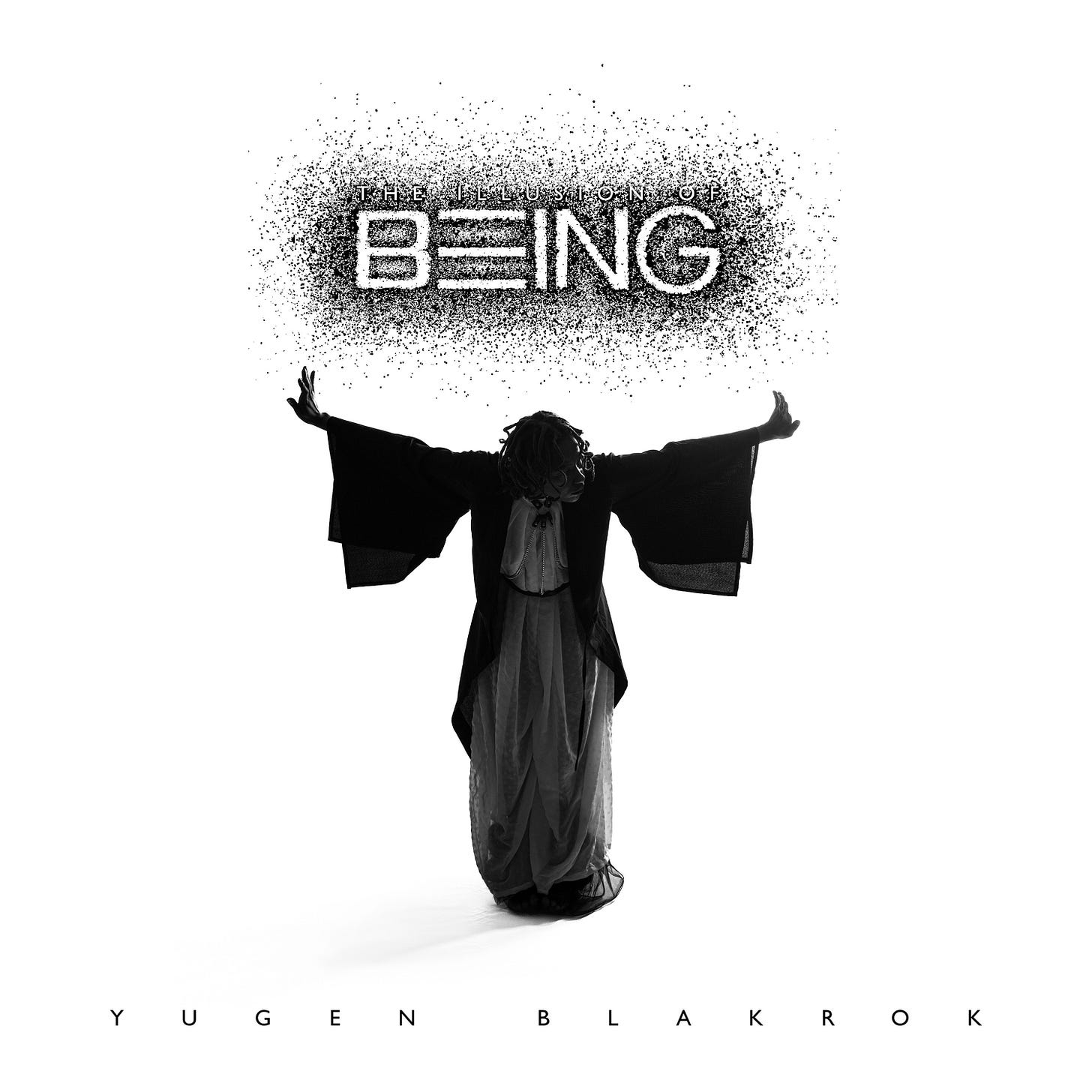

Yugen Blakrok, The Illusion of Being

Yugen Blakrok’s second full-length since 2019 opens in near darkness, “Mesmerize” pacing over murky analog bass and vinyl crackle while Loudmic’s scratch work circles like a vulture. Her delivery is measured, almost meditative, yet every internal rhyme detonates on the down-beat, turning the track into a slow-burner that refuses the dopamine rush of contemporary trap templates. Throughout, the emcee pokes at certainty itself—“Absolute truth is just a myth in this reality/Like the gender of God…” she spits on “Earthlinguist,” teasing cadence until the beat seems to hold its breath. Kanif the Jhatmaster’s beats avoid maximalism, favoring negative space and low-pass grit that recall Company Flow’s early tectonic rumble more than glossy modern boom-bap. Cambatta turns “Tessellator” into an occult cypher of syllable flips while Sa-Roc’s razor-sharp counter-flow on “The Grand Geode” feels like two griots carving hieroglyphs into the same stone in real time. A broken-time snare pattern jitters beneath guitars and swirling synth arpeggios while Blakrok spits “I bend light around my name,” collapsing cosmic physics into street-corner bravado. Rather than a victory lap, the fade-out opts for unresolved chords, implying that transcendence is a process, not a destination. — Brandon O’Sullivan

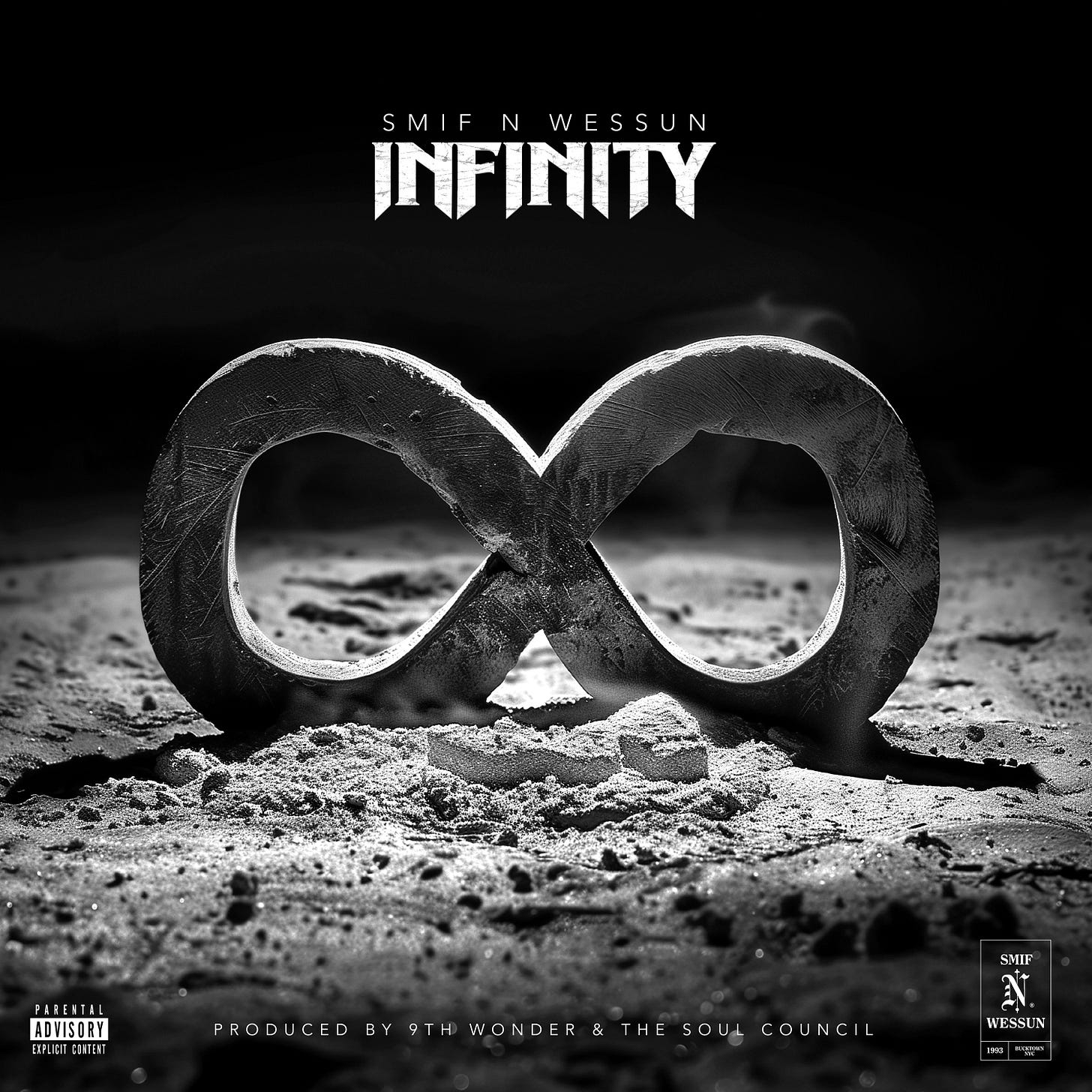

Smif-n-Wessun, Infinity

Three decades after their debut, Tek and Steele sound newly urgent, rhyming as if the next loop might disappear forever. Early teasers framed Infinity as both anniversary toast and open challenge, a promise fulfilled by the record’s rugged breakbeats and dig-in-the-crates sample chops. The entire project is steered by 9th Wonder and the Soul Council, whose arrangements fuse dusty snares with gospel-organ swells that nod to the duo’s spiritual resilience. Opener “Infinity” hurls you into siren wails and patois-flecked call-and-response, reminding listeners of the Caribbean inflections that have always set Smif-n-Wessun apart. “Medina,” propelled by a snarling Pharoahe Monch verse, flips a minor-key guitar figure into a Brooklyn street opera, while “Namaste” lets newcomer Sweata lace a melodic hook over swirling strings before Tek snaps back with hard-earned serenity. The record’s emotional apex, “Black Eminence,” stitches posthumous bars from Prodigy into a mournful trumpet loop, turning memorial into marching orders for anyone still fighting fatigue. If the message on “On My Soul” is blunt—“peace in my mind lasts longer than beef on the block”—the delivery is anything but didactic, carried instead by voices that have earned every ounce of their authority. — LeMarcus

John Glacier, Like a Ribbon

Between 2020 and 2021, John Glacier forged a distinctive voice amid an era of lockdowns. The album’s producers—Flume, Evilgiane, Kwes Darko, Andrew Aged, Harrison, Zack Sekoff—warp drums until they flicker like faulty streetlights, leaving Glacier’s voice to drift in and out of focus. She opens “Satellites” mumbling through reverb haze, syllables slicing the mix like paper cuts before a sudden bass surge resets the pulse. The record’s emotional anchor is “Ocean Steppin’,” where she raps, “Ocean steppin’ on shores/Crash the wave, then I pause/Bring it back to the land,” turning seascape imagery into a metaphor for psychic ebb and flow. That push-and-pull defines the sequencing: “Money Shows” smears Eartheater’s spectral co-lead across trap triple-hi-hats, then “Found” drapes half-remembered piano over clipped jungle breaks. Glacier’s deadpan delivery disguises barbed confessionals—references to “sleeping in the park ’cause the rent made no sense” land like passing thoughts, all the more devastating for their casual tone. Observers of her live sets describe the record as split into movements that mirror the ways a ribbon curls, falls and snaps back, and that metaphor tracks: energy coils tightly on “Nevasure,” slackens into ambient murmur on “Steady As I Am,” then whips up into break-beat turbulence on “Home” before settling into the whispered finale “Heavens Sent.” — Nehemiah

Backxwash, Only Dust Remains

Backxwash continues her excavation of trauma, faith and trans embodiment, but here the sonic palette loosens: doom-metal guitars still roar, yet “Black Lazarus” rides a swung break-beat before detonating into double-kick mayhem while she spits, “my old friends keep on reaching out like they hearing you got demons—how?” “Wake Up” stretches to seven minutes, cycling from whispered lament to industrial blast beats and back, mirroring the lyric’s oscillation between suicidal ideation and the videogame spark of staying alive one more day. The record closes with “9th Heaven,” a dirge-turned-hymn whose organ drones crumble under distorted 808s, suggesting redemption is possible only through loud and unvarnished confession. In turning horror-rap’s aesthetics inward, Backxwash finds communion not in absolution but in the shared feedback loop of pain transmuted to art. — Brandon O’Sullivan

MIKE & Tony Seltzer, Pinball II

On the surface, this sequel feels louder and brasher than the smoked-out haze that earned MIKE a cult following, yet its core remains diaristic. Tony Seltzer’s drums snap like broken arcade bumpers over chopped guitar squeals that crib from horror-score dissonance and litefeet’s whiplash kinetic swing, giving MIKE permission to rap with a bared-teeth confidence he once reserved for private notebook entries. “WYC4” inverts hustle-culture clichés by framing success as an act of spiritual hygiene, while “#71” stacks claustrophobic phrases into a mantra that collapses into a beat switch worthy of a slasher jump-cut. When Earl Sweatshirt crashes “Jumanji,” the song turns into a cypher about survivor’s guilt that’s both playful and bruised. The album’s emotional ballast, though, is “Chest Painz,” where MIKE’s voice fractures under the weight of a lost friend’s voicemail, proving that vulnerability can coexist with swagger without cancelling either out. — Nehemiah

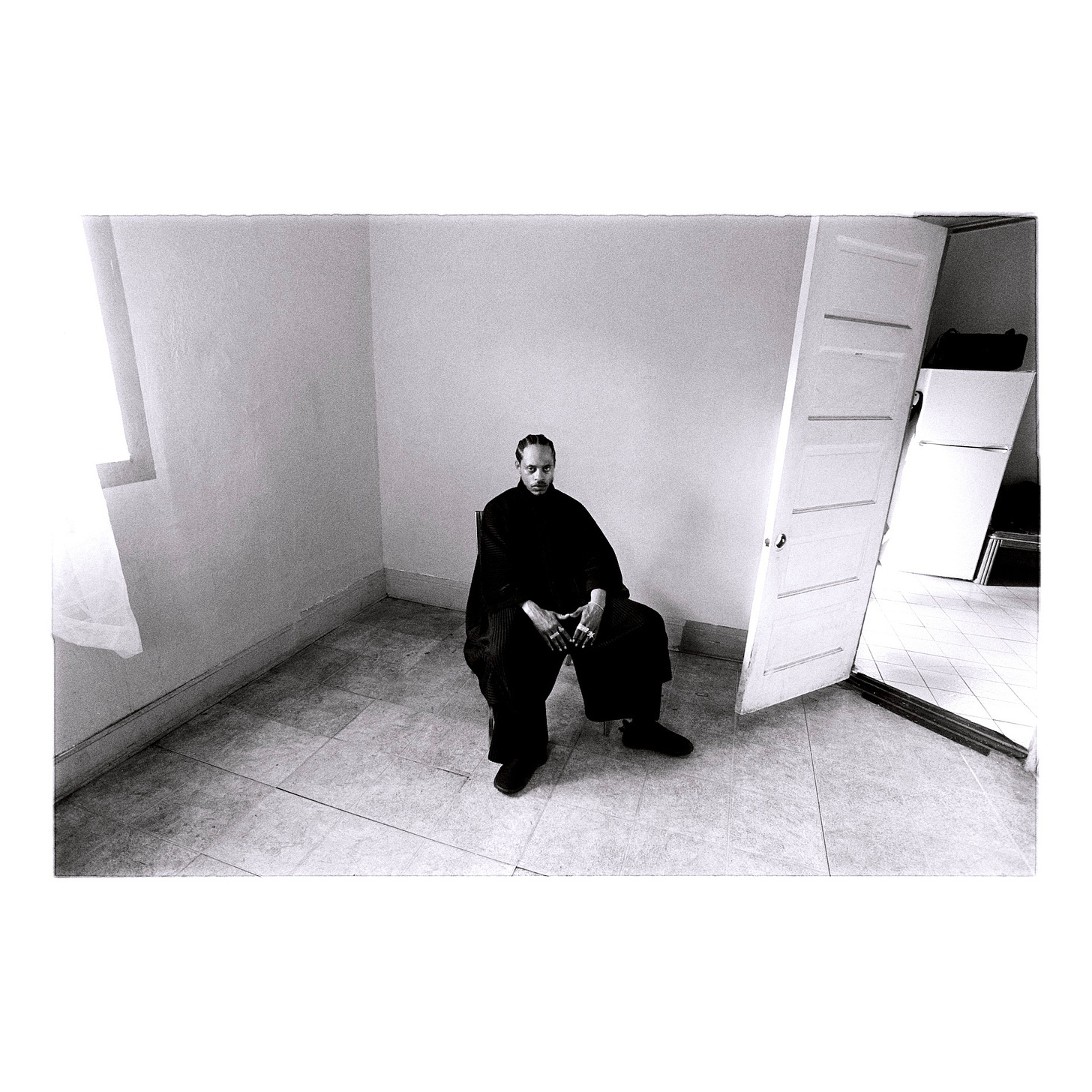

Knowledge the Pirate & Roc Marciano, Round Table

Roc Marciano’s loops here barely clear the noise floor—hushed Rhodes phrases, brittle snare taps, leaving Knowledge’s gravelled baritone to fill the frame. Opening salvo “Eating Etiquette” reimagines fine-dining manners as codes for dope-game discretion; lines about “forks and knives” resurface later as metaphors for friends who cut both ways. The lone posse moment, “The Outfit,” finds Roc himself stepping from behind the boards to swap weary boss talk in eight-bar bursts, the pair sounding like chess partners mid-match rather than rivals. Across the album Knowledge revisits maritime lore—“Addicted to Danger” compares a cracked hull to a bruised ego, and closes on “Receipts,” a recounting of debts paid in blood that fades under creaking ship-rope samples, tying the crime narratives back to the title’s code of honor. — Javon Bailey

Brother Ali, Satisfied Soul

Brother Ali’s first full-length since Love & Service opens with a prayer, then sweeps forward on verses that fuse mystic awe with street-level witness. The title song’s refrain (“My mouth is a fire starter/My eyes spout water/My body in the drama”) sits at the heart of the record, a mantra that frames rhetorical ferocity as a tool of healing rather than domination. Throughout, Ali raps not to broadcast credentials but to excavate contradictions: compassion under siege, devotion tested by ego, hope flickering inside structural violence. Mid-album passages linger on family—he invokes his daughter and late father in the same breath, suturing generational grief to a vow of stewardship. His imagery retains the tactile immediacy that marked Shadows On the Sun, yet the tone is lighter, almost serene; he has traded the blunt protest of “Uncle Sam Goddamn” for contemplative lines that treat justice work as lifelong ritual, not campaign slogan. When he cautions “the only person that can injure me is my own self,” the epiphany lands without self-help platitudes because the verse has already shown the cost of letting anger curdle into dogma. While Ant’s drums still boom in the low end, the beats leave space for Ali’s cadence to rise and fall like spoken-word recitation rather than strict sixteen-bar form. — Javon Bailey

MIKE, Showbiz!

MIKE threads his voice through tape-warped soul snippets that feel rescued from half-remembered afternoons; the sequence rushes by in miniature vignettes, most under two minutes, yet each one lands like a Polaroid of a mood you once thought was private. He constructs nearly the entire sound-bed himself under the DJ Blackpower alias, layering sub-bass, brittle drums, and stray gospel hums until the surface crackles like old acetate The brevity isn’t gimmickry as it mirrors the scribbled-in-transit quality of his writing, a stream of consciousness that moves from grief to gratitude without warning. On “Watered Down,” a single line—“That’s my sister, treat her like my daughter, really”—condenses a family history into ten words, then dissolves into a woozy Rhodes run that never resolves. Moments later, the beat switch in “What U Bouta Do?/A Star Was Born” opens space for 454’s helium blur, underscoring how camaraderie interrupts MIKE’s interior monologue just long enough for sunlight to leak in. — Harry Brown

Rome Streetz & Conductor Williams, Trainspotting

Conductor Williams supplies sample-centric beats marked by mid-tempo drum hits and brief horn chops, giving Rome Streetz a stable runway for intricate rhyme chains. “Andre Agassi” introduces terse internal patterns that parse risk and reward without ornamental slang. Method Man’s verse on “Ricky Bobby” floats over a sparser arrangement, highlighting generational contrasts in delivery while keeping the focus on cadence. Jay Worthy steps into “10 Toes” with a smoother drawl that never softens the grit of Rome’s syllable stacks. Short interludes, such as “Connie’s Revenge,” reset the ear, each built from a single loop that drops out before it can blend with the main tracks. When the theme shifts to industry pitfalls on “Rule 4080,” Conductor pares the beat back to a hi-hat pattern, letting contract-law references land without distraction. A late track called “Electric Slide” introduces a bright keyboard figure, offering tonal lift before the sequence settles back into weightier textures. The partnership succeeds because neither artist overplays; space in the mix carries as much attitude as any rhyme. — Reginald Marcel

Denzel Himself, Violator

Denzel Himself’s first full-length feels like being dragged through a neon-lit Western run by punks and prophets. Self-produced from top to bottom, the record welds gnarled break-beats and distorted bass to flashes of choral synths, then sprays the mix with guitar shrapnel that nods to industrial and shoegaze. Tracks such as “Goth Los Angeles” and “Kowgirl Manifesto” swing between whispered spiritual confessions and barked threats, the MC bending his voice from sullen croon to throat-ripped howl while live drums pummel like a hardcore set crashing an art-rap gig. All the twitchy micro-edits and sudden tape-stop drops serve a bigger picture: a synaesthetic swirl that mirrors the artist’s own description of experiencing “Dilla’s brain in Manson’s skull.” Beneath the shock value sits an unabashed love letter to music itself. Multiple interludes stitch diary-level monologues to vapor-trail vocal harmonies, casting the LP as a healing ritual; he calls it “my love letter to music” in the liner notes, where vengeance fantasies and tenderness trade verses. Underneath the noise lies a straightforward argument by refusing to adhere to genre etiquette can itself be a spiritual practice, and distortion can be as cleansing as a choir. — Brandon O’Sullivan

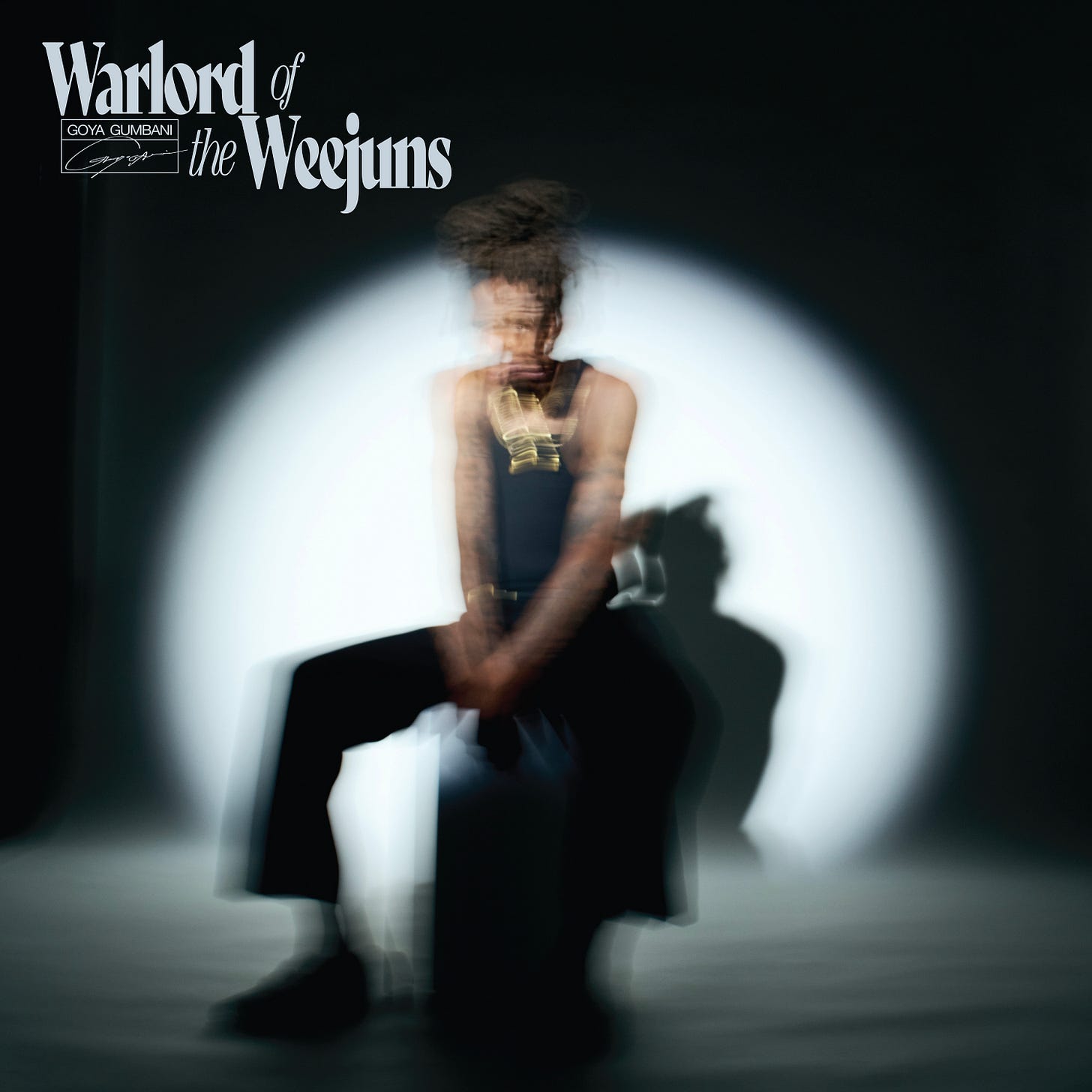

Goya Gumbani, Warlord of the Weejuns

Gumbani keeps the tempos unhurried, letting brushed drums, upright bass strolls, and Joe Armon-Jones’s keys breathe like late-night club smoke. The opening statement “Beautiful Black” slides between hymn and self-portrait, his voice almost conversational as he insists on radiance in every bar. When lojii joins him on “One Hand Washes the Other,” the verses fold generosity into creed: each line feels hand-stitched, no seams showing. The album peaks during “Chase the Sunrise,” where Fatima’s soprano flutters above woodwind flourishes, turning a simple pursuit of peace into a communal sunrise service. Across sixteen tracks, the rapper’s Brooklyn drawl and London cool blur; you catch Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word cadence one minute, Mic Geronimo’s sneak-rhythm phrasing the next, yet the center never wobbles because his writing—half prayer, half diary—keeps circling back to dignity and everyday faith. — Randy

Ovrkast., While the Iron Is Hot

Ovrkast. pares his first solo release in almost five years, which moves like bursts of adrenaline. Quick entries, abrupt exits, always something new around the corner. Lo-fi drum chops and tape-warped piano lines dominate, yet flashes of brightness—glassy synth sprinkles, a surprise brass swell—keep the color palette vivid. Verses toggle between internal monologue and neighborhood snapshots; one moment he’s checking vitals on his creative drive, the next he’s laughing at a corner-store misunderstanding. The pacing feels almost punk as most songs clear the two-minute mark only long enough for a hook to lodge, then cede space to the next idea. Samara Cyn, Vince Staples, MAVI, and Saba stop by, not for marquee moments but for counterpoint, mirroring Ovrkast.’s restless tone. A mid-album highlight, “Strange Ways,” slips from skeletal loop to full-band crash before the listener can decode the pivot, illustrating the record’s thesis that urgency can be its own kind of cohesion. — Nehemiah

Excited to dig into this. So much here!!