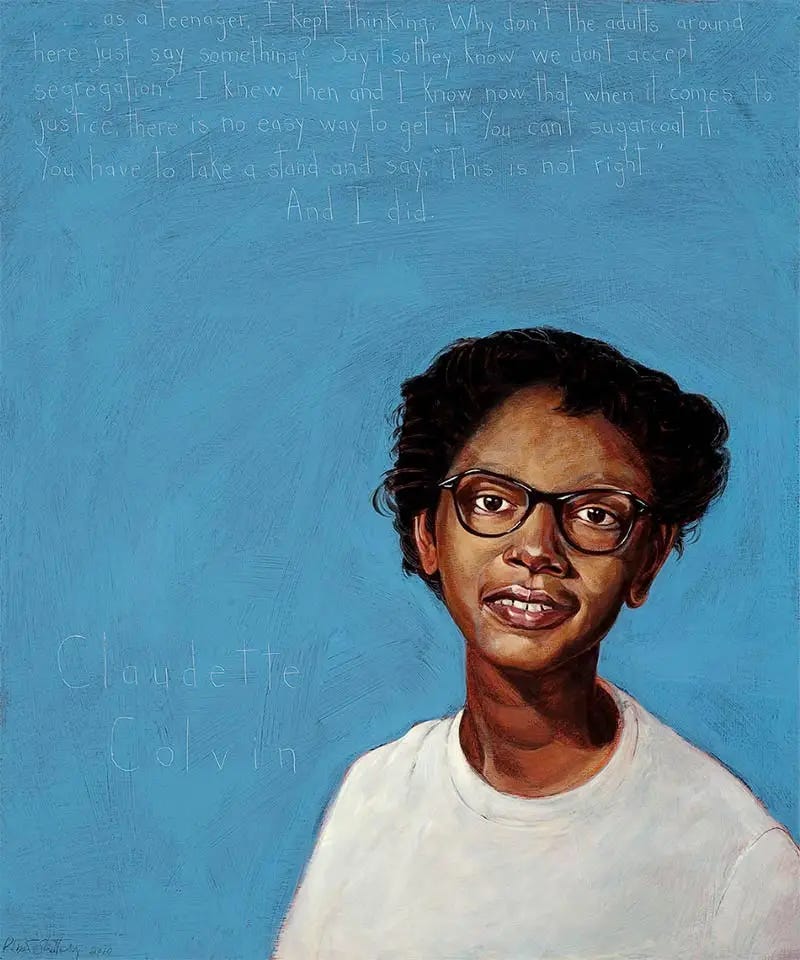

The Girl Who Would Not Move

Claudette was fifteen, tired of being ordered smaller, and clear about her rights. Her refusal came before the cameras were ready and before history decided who felt safe enough to remember.

A four-year old Claudette Colvin was standing in line at a general store in Pine Level, Alabama, when a white boy cut in front of her. Older white kids came through the door laughing, pointing at her, wanting to see her hands. She held them up, palms out, and the boy pressed his against hers. The laughter doubled. Her mother saw the white boy’s mother watching and crossed the room fast. She backhanded Claudette across the face. “Don’t you know you’re not supposed to touch them?” The white woman nodded at Mary Ann Colvin and said, “That’s right, Mary.” That was how Claudette learned the rule: never touch another white person again.

The rule repeated itself in a hundred small ways as she grew. When she needed shoes, her mother traced the shape of her feet on brown paper and carried the outline to the store because Black children could not try anything on. When Claudette found a beautiful Easter hat she wanted, the white saleslady kept pulling out different hats, refusing to let her have the one she pointed to. Claudette got angry and said something about the woman’s ears sticking out. Her mother covered her mouth and marched her out of the store. When she went to the optometrist, the doctor told her and her father to leave and come back at the end of the day. No white patient would sit in a chair that a Black child had sat in first.

When she entered Booker T. Washington High School, Claudette had absorbed two decades of accumulated indignity that had nothing to do with what she deserved. She was dark-skinned in a school where light skin and straightened hair determined social standing. She was from King Hill, a neighborhood that meant “poor” to people who did not live there. She was younger than her classmates because teachers had twice pushed her ahead a grade. When she was thirteen, her sister Delphine died of polio on Claudette’s birthday. Something hardened in her after that. She asked her pastor why God would curse just one race. She refused to believe it.

Her teacher, Geraldine Nesbitt, had a master’s degree from Columbia and brought her own books to school because the segregated library had almost none. Negro History Week in February 1955 turned into something closer to total immersion. The Constitution, the Fourteenth Amendment, and Harriet Tubman. “Why do we celebrate the Fourth of July when we are still in slavery?” Miss Nesbitt asked, while Claudette absorbed it. She was done talking about “good hair” while the daily insults went unaddressed.

On March 2, 1955, she was fifteen years old, sitting on a Montgomery city bus behind the white section, textbooks on her lap, blue dress smoothed down. A white woman appeared in the aisle. The three other black students in Claudette’s row stood up and moved. Claudette did not. The driver shouted. She stayed. He radioed for police. When two officers boarded and loomed over her seat, she started crying but did not move. “It’s my constitutional right to sit here as much as that lady,” she said, her voice high and scared and loud. “I paid my fare, it’s my constitutional right.” They grabbed her wrists and pulled her straight up out of her seat. Her books went flying. They dragged her backwards off the bus. One kicked her. She went limp. She kept screaming about her rights.

In the squad car, handcuffed through the open window, she recited the Lord’s Prayer and the Twenty-third Psalm while the two cops talked about her body. They guessed her bra size. They called her “nigger bitch” and cracked jokes about parts of her anatomy. She assumed they were taking her to juvenile court. She was thinking about picking cotton, because that was how they punished teenagers. Instead, they drove her to the city jail, in other words, the adult jail. They booked her and walked her to a cell and shut the door behind her. The lock fell with a heavy sound. “It was the worst sound I ever heard,” she said later. “It sounded final. It said I was trapped.”

Her classmates split into factions when she returned to school. Some admired her. Others said she should have known what would happen, that she made things harder for everyone. They pointed at her in the halls. Teachers seemed uncomfortable. Adults in her neighborhood kept distance. Black leaders investigated her background: working-class parents, a small frame house on King Hill, and a church for the poor. The adjectives started circulating. Emotional. Feisty. Uncontrollable. Too young. The Women’s Political Council decided she was not the right person to represent a citywide bus boycott.

Claudette responded in the only way left to her. One Saturday, waiting to go to the beautician to get her hair straightened, she stopped herself. She went into the kitchen and washed her hair and pulled it into little braids while it was still damp. When she walked into school on Monday, the reaction was shock. Teachers asked why she would do such a thing. Classmates said she was still grieving Delphine. Her boyfriend kept asking why she wouldn’t straighten her hair. She told him it looked African, and she was proud of it. Back then, she said, nobody used the word “African.” Africa meant Tarzan. You were supposed to be ashamed. She was not ashamed. All spring, she heard the same word: Crazy. Crazy. Crazy.

That summer she got pregnant. The father was a man ten years older, married, someone who had seemed to understand her when everyone else called her mental. Her mother nearly collapsed when she found out. Her father threatened to kill the man. Claudette’s parents told her not to name him, and she obeyed. She started showing too early. The school expelled her. When the boycott leaflet came in December 1955 after Rosa Parks was arrested, Claudette saw her own name misspelled: “Claudette Colbert.” No one had called to ask how to spell it.

But Fred Gray called in January 1956. He was filing a lawsuit against the city of Montgomery and the state of Alabama (Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707), arguing that segregated buses violated the Fourteenth Amendment. He needed plaintiffs who would sit in a witness box and face white lawyers and white judges and tell the truth about what had happened to them. Claudette said yes. She was seven months pregnant. She gave birth to her son, Raymond, on March 29, 1956. Fast forward six weeks later, she walked into a federal courtroom.

When the city attorney Walter Knabe pressed her about whether Reverend King had put the boycott in motion, she cut him off. “Did we have a leader? Our leaders is just we, ourselves.” He kept asking about King. She widened her eyes. “Are you trying to say that Dr. King was the leader of the whole thing?” He tried again. She answered, “Quite naturally we are not going to have any ignorant person to lead us.” The judge told her to stop making speeches and just say yes or no. She did, until Knabe asked the question that went to the heart of the case.

“Why did you stop riding the buses on December fifth?”

“Because we were treated wrong, dirty and nasty.”

Spectators murmured yeses in response.

On June 19, 1956, the federal court ruled 2–1 in favor of the plaintiffs. Segregated bus seating in Alabama violated the Constitution. The Supreme Court affirmed the decision in November. The buses were integrated in December. Claudette was not on the first integrated bus ride. No one invited her. She was still an unwed teenage mother with a light-skinned baby and a name people preferred not to say out loud. She needed money and kept getting fired from restaurant jobs when employers found out who she was. In 1958, she followed her cousin to New York. She worked as a nurse’s aide in a hospital for decades, told almost no one what she had done, and kept her phone number unlisted. She raised two sons. The door to her place in history stayed closed until a reporter found her parents’ old number in a Montgomery phone book in 1975 and called.

She went back on February 3, 2005, for a fiftieth anniversary commemoration. She stood before the students of Booker T. Washington High School, the school that had expelled her. A Black girl and a white girl stood on either side of her for a photograph. She told them don’t give up, keep struggling, and don’t slide back.

“If you see some injustice going on, something that you think is not right, you feel that it’s wrong, don’t be afraid to stand up. Because if you stand up, most of the time, one person stands up, someone else, you may be another person standing up with you. But stand up if you have to stand up alone. Stand up because you make the sacrifice and you make it better for someone else.” — Claudette Colvin at the San Francisco Public Library

Thank you to Phillip Hoose and the book, Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice.

Given our current climate, we need to be reminded that there is something we all can do to protect our freedoms.