The Handguide to Backwoodz Studioz

These releases chart the moment when Backwoodz Studioz forged its signature alloy of literary street rap, deconstructed samplecraft, and anti-imperialist critique.

Backwoodz Studioz began as a guerrilla operation determined to smuggle dense, idea-heavy New York rap into a marketplace that rarely rewarded risk, and the early catalog you asked for maps the label’s formative tension between raw immediacy and painstaking world-building; what follows is a continuous, album-by-album traversal of that first explosive stretch, tracing how each project chisels another facet into the imprint’s larger aesthetic, foregrounding the sound of cracked vinyl drums, grim brass loops, and verses that treat history, geopolitics, and street reportage as interchangeable currencies.

billy woods, Camouflage

billy woods’ debut moves like a restless night patrol as percussion clacks echo off brick alleys while minor-key horns drift in and out like searchlights, and woods’ voice (already gravelly, already impatient) threads through samples of war reportage and late-night jazz broadcasts to build a paranoid travelogue that shifts from post-9/11 Washington to a metaphorical Saigon without ever changing subway lines. Collaborative fingerprints animate the record: Bond’s distortion-heavy bass on “Minimalism” rumbles beneath couplets about gentrification and Ugandan coup d’états, while Vordul Mega drops spectral cameos on “Poli-Sci” and “Macross Plus,” his half-mumbled internal rhymes mirroring woods’ clipped reportage in a tag-team critique of American empire. The track sequence refuses comfort; hooks are fleeting, tempos lurch, and sudden dub interludes (“The Things They Carried”) let blown-out brass smear across the stereo field before the next barrage of rim-shots arrives. The resulting mood is trench warfare rendered through boom-bap: every snare crack feels like incoming fire, and every bar, packed with references to Graham Greene, Patrice Lumumba, and ghetto-bird spotlights, insists that personal autobiography and world history are never separate theaters of operation.

billy woods, The Chalice

If Camouflage was reconnaissance, The Chalice is a siege: longer, denser, and drunk on its own vocabulary. The opening “Killtro/Go-Go Dub Plate” stages a noisy block-party inside a bunker: DC percussion rattles under a chopped reggae bassline while woods snarls about media propaganda and fentanyl-laced dime bags, refusing the escapism suggested by the beat’s celebratory whistles. Across twenty-one tracks woods stacks voices—Vordul Mega’s brittle monotone on “Mindcontrol,” Priviledge’s smoke-stained drawl on “Blowout,” Vast Aire’s wing-spanned multis on “Drinks”—into a crooked choir, each cameo sharpening the record’s obsession with systems that chew people up, from Cold-War covert ops to predatory payday loans. Production leans darker than before. Bond feeds Rhodes chords through dusty filters until their harmonic centers fray, and sudden bursts of conga-led go-go jog the tempo forward only to be ambushed by saw-toothed synths. By the time the closer “Origami Paper” dissolves in tape hiss and distant church bells, The Chalice feels less like an album than a classified dossier—page after page of redacted trauma slowly revealed under a black-light beat tape.

The Reavers, Terror Firma

Terror Firma corrals a who’s-who of early-‘00s New York underground radicals—AKIR, Hasan Salaam, Karniege, Spiga, woods himself—into a loose federation that treats the studio like a crowded planning cell. The production palette is gothic: low-passed choirs moan beneath minor-third horn stabs, while snares crack with the metallic ring of scaffold pipes. On “Slums,” dual bass riffs grind like tank treads as AKIR juxtaposes U.N. sanctions with corner-store stickups; “Penmanship” answers with strained strings and a drum loop chopped just off-grid, forcing MCs to fight the beat’s stutter the way their verses fight civic neglect. The record’s emotional center is “Shadows,” where woods and Karniege trade vignettes about police surveillance and post-colonial shadow wars, the hook drenched in reverb until it sounds like it’s being sung down a prison hallway. Terror Firma’s greatest trick is scale: one minute the focus tightens to a single apartment eviction, the next it zooms out to drone strikes over Fallujah, and the clamor of nine separate rhyme styles only amplifies that widening gyre.

Keith Masters, Bioluminescence (EP)

Keith Masters’ introductory suite glows like its title, where synth pads shimmer with aquatic luminescence while hi-hats flicker in triplet syncopation, giving even his punch-line-heavy flows a phosphorescent after-image. “Write This Way” flips a dusty soul sample, chopping the vocal on the off-beat so that Masters’ reflections on ambition punch through gaps like flashes from deep-sea anglers. Elsewhere, “12:31” rides a woozy Rhodes riff, Masters toggling between political jabs and playful anti-vegetarian boasts, playing with tone the way the beat plays with phase. Despite its mixtape origins, the transitions are album-tight, stitching into a narrative about survival through self-illumination, so that by “Where Did Life Go Wrong,” the EP feels like a single exhale rising toward the surface.

Bond, Golden Gunn

Bond’s lone solo statement is a producer’s diary masquerading as a rap album: loops run long enough to expose their splices, vocal takes bleed into rough drafts, and the mix occasionally overloads, all of which underline Bond’s fascination with process over polish. The title piece welds spaghetti-western guitar twang to brittle MPC drums, turning the studio into a windswept mesa; Bond’s verses echo that imagery, comparing dusty reel-to-reel tape to desert sand and labeling his drum machine “the last revolver in a lawless town.” Certain tracks drop the tempo beneath 80 BPM, allowing cello drones to shadow Bond’s slow-rolling syllables and giving the record a psychedelic bent that anticipates later Backwoodz work with Messiah Musik and Steel Tipped Dove. Despite the raw edges, Golden Gunn’s sequencing is surgical that each beat change feels like turning another page of Bond’s field notebook, charting the distances between Brooklyn rooftops and tumbleweed silence.

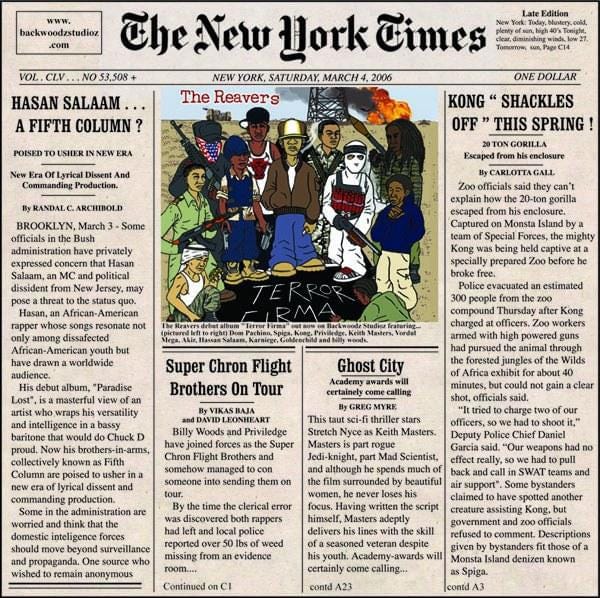

The Reavers, New York Times

Cut together during the same season of frantic studio lock-ins that birthed Terror Firma, this guerrilla mixtape treats the titular newspaper as both enemy intel and scrap collage. Tracks fade abruptly, verses overlap like competing headlines, and the mastering stays purposefully hot, evoking tabloid presses rattling at 3 a.m. Unlike the previous efforts meticulous arrangements, New York Times is immediate, its structure more warehouse show than album arc, which only heightens its urgency: this is breaking news delivered before facts can be laundered for polite consumption.

Backwoodz Studioz Presents: Target Practice

Designed as a label sampler, Target Practice feels like edges of a family photo album—each snapshot capturing artists mid-mutation. Because the compilation shuffles MCs and beat-makers every few minutes, the through-line becomes attitude: skepticism toward empire, fascination with linguistic minutiae, and a willingness to warp beloved samples until they snarl. Rather than a simple commercial card, the record functions like a sonic manifesto, announcing Backwoodz’ intent to privilege experimentation over radio-readiness.

Super Chron Flight Brothers, Emergency Powers

Before the duo ever stepped onto the second leg of their “World Tour,” Emergency Powers had already drafted the flight plan by delivering an hour-plus of densely packed vignettes in which billy woods and Priviledge turn every customs line, war dispatch, and back-alley baggie into proof that local anecdote and global power play the same game on different boards. Emergency Powers was the opening chapter of a larger itinerary; later projects would take the group to Indonesia and Cape Verde, but here, the group stays in perpetual take-off, cataloguing the underbelly of every layover city in rapid-fire snapshots that flicker by like runway lights at midnight. On “Drought” the kick drum lands fractionally ahead of the quantized grid while a wheezy organ sample drifts behind, producing rhythmic glare that mirrors the hook’s complaint about empty harvests in city tenements and Sahel deserts When MF DOOM’s lone contribution, “Dirtweed,” rolls in, the tempo slackens and the drums splutter under a woozy Rhodes figure pitched somewhere between reggae skank and carnival dirge, giving woods room to sketch a transnational supply chain where South-American brick, Harlem corner, and IMF loan document occupy the same three-bar loop.

Keith Masters, Masters of the Universe

Built as an expansive mixtape but sequenced like a formal LP, Masters of the Universe spins twenty tracks over glitchy boom-bap and early-‘00s chipmunk-soul flips. “About to Drop” rides over Jigga’s “Show Me What You Got” while Masters offers a meta-narrative about his own hustle; “Wheight” flips Juelz Santana’s “Oh Yes” into a critique of trap-era coke braggadocio, indicting both corporate dealers and government enablers in one run-on stanza. The tape’s thematic engine is plurality: Masters toggles flows so quickly that traditional notions of rapper persona blur, and the beats follow suit, jumping from dusty crate-digging to space-synth bounce without announcing key changes. The effect is centrifugal—every track spins out new fragments of Masters’ musical identity yet somehow circles the same nucleus of self-determination through craft.

Invizzibl Men, The Unveiling

Karneige and MarQ Spekt’s duo album crackles with basement-show electricity: lo-fi drum programming pops like vinyl static while horror-movie strings saw beneath Spekt’s gravelly ad-libs. The title track opens with a preacher’s sermon abruptly looped into a rhythmic mantra, setting a theme of revelation-as-threat; lyrics jitter between street allegory and occult imagery, so that a corner sale in Brownsville morphs into a Tarot draw predicting civil unrest. Mid-sequence cut “Thi Ayers” layers hard hitting-drums over chopped operatic sample, mirroring the duo’s lyrical gumbo of diaspora references. What distinguishes The Unveiling is its resistance to tidy catharsis as verses end mid-thought, beats stop on inhale, and the final track dissolves into distant thunderclaps, leaving the curtain perpetually half-drawn.

Vordul Mega, Megagraphitti

Long gestating, Megagraphitti sounds like an archival time-capsule unearthed and re-sequenced by its own subject; MPC snares from the early-‘00s sit beside later, smoother jazz-loop experiments, and Vordul’s monotone weaves through both eras unchanged, turning his voice into the project’s moral anchor. “Peanut Butt Ups” suspends a mournful flute riff over minimal drums, Vordul unpacking PTSD from Harlem housing projects while packing rhymes in the same breath; “Trigganomics” flips Isaac Hayes strings, letting guest Karniege’s double-time verse spark against Vordul’s stoic delivery. The record’s cumulative effect is mosaic: shards recorded across half a decade align into a bleak portrait of urban survival painted in muted earth-tones, proof that time gaps can deepen rather than dilute artistic coherence.

MarQ Spekt & Lex Boogie, Guilty Party

Guilty Party strips Backwoodz’ dense politicism down to asphalt-level grime: Lex Boogie laces crusty SP-1200 breaks with shards of blues guitar, and Spekt locks into knotty internal-rhyme barrages that evoke ‘95 basement cyphers. On “BangLadesh,” the beat loops a sitar sample into menacing twang, Spekt responding with jittery pocket shifts that turn every snare into a haymaker; “Jetlag” follows by chopping gospel hand-claps into strobe-light punctuation, Spekt tracing global flight paths of contraband while dismantling rap-industry clichés. The album’s pacing mirrors an illicit stakeout: short instrumental “GUILTYLUDE” sketches catch-breath shadows, then the next track bursts with pent-up aggression. By foregrounding raw texture over polish, Guilty Party positions itself as both homage to mid-‘90s cassette culture and critique of over-compressed modern rap aesthetics.

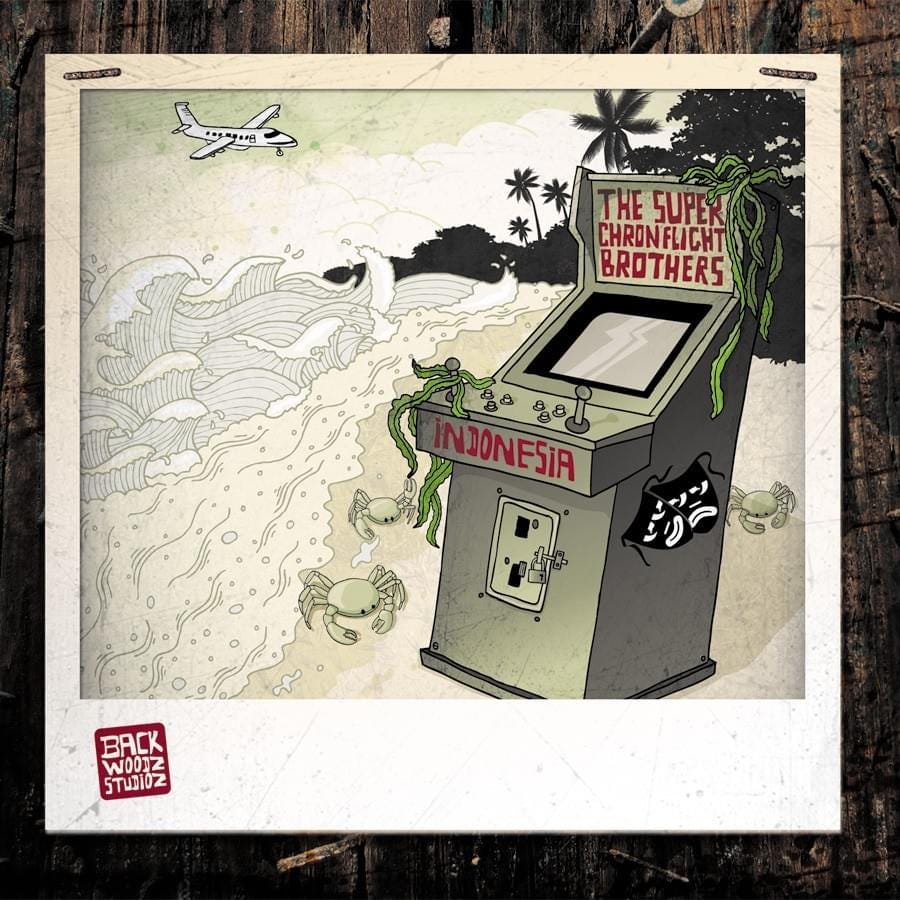

Super Chron Flight Brothers, Indonesia

The second Flight Brothers installment pushes the duo’s “World Tour” concept to its psychedelic extreme. The opening track, “Xanax,” warps Indonesian gamelan bells into a seasick carousel around which woods deploys baroque colonization metaphors and Priviledge sketches import-export scams on black-market shipping lanes. Because the album circulated as a free digital leak before being pressed to double CD, its sample sources shift continents mid-bar, and extended outros let dub delays swallow whole hooks. “John McCain” has this frantic beat over sub-bass swells, the beat lurching like a cargo freighter in rough surf, while “Gatwick” is built around weird drum sounds and drained-battery synth drones, turning ecological disaster into a final word on imperial hubris. Indonesia embodies Backwoodz’ early experiment, which treats every beat like a shipping container of contraband ideas, cracking it open and letting the listener sort through the fallout.

Super Chron Flight Brothers, Cape Verde

Released as the duo’s swan song, Cape Verde doubles down on the blunted paranoia of its predecessors while inviting a rogue’s gallery of guests—Bigg Jus, Vordul Mega, Lord Superb, Masai Bey, Hi-Coup, Pastense, Zesto—into the war room, a move that turns every verse into both confession and cross-examination. The sonic backdrop, stitched entirely by Bond and Willie Green with a brief assist from NASA, is metallic and cavernous, as though the drums were recorded in an abandoned dry dock, and the bass lines keep plunging until they hit that sub-frequency band where anxiety becomes physical discomfort, fulfilling the album’s mission to soundtrack an end-of-empire hangover even when the tempo drifts toward boom-bap bounce.

A.M. Breakups, The Cant Resurrection

Pieced together between 2006 and 2009, this producer album feels like a sonar read-out of late-night Brooklyn: layers of detuned Rhodes, clipped vinyl crackle, and rhythmic glitches shuffle past like subway cars in a tunnel, each carrying samples of overheard arguments, storefront radios, and busted streetlights humming at different voltages. Breakups treats every sound as potential archeology; a chopped gospel chord floats across the stereo field only to be swallowed by a pulverized breakbeat, suggesting that even hope gets looped and resold in the nocturnal marketplace the record documents.

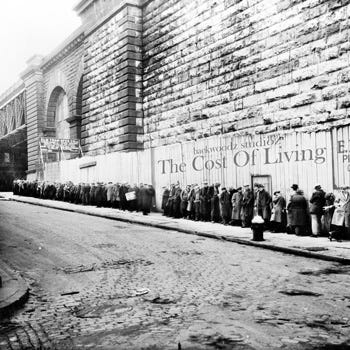

Backwoodz Studioz, The Cost of Living

Framed as a label mixtape in 2011 but sequenced like an agit-prop mural, The Cost of Living pulls MCs from every corner of the Backwoodz orbit—ELUCID on the demolition-anthem “Demolition,” billy woods scheming in “Six Flags,” Open Mike Eagle clown-masking gentrifiers on “The Knock”—and sets them against beats that crackle with loose wires and factory grit. Its track list reads like a roll call of underground resistance, and the sequencing carves a narrative arc from rent-is-too-high gallows humor to the cold dawn of eviction trucks, making the compilation feel less like label sampler and more like collective survival manual.

billy woods, History Will Absolve Me

The 2012 watershed where woods’ dense reportage, magpie sense of history, and sardonic punchlines finally fused into a single, combustible voice. Production from Marmaduke, A.M. Breakups, Willie Green and others swings from flute-loop claustrophobia on “Body of Work” to cartoonish menace on “Bill Cosby,” forcing woods to adapt flow and cadence like a field operative switching dialects. Verses reference La Violencia, diamond-trade cartels, and Harare childhood memories with the same weary precision, turning each track into a dossier page; cameos from Roc Marciano and ELUCID land like classified footnotes, verifying the intel rather than distracting from it.

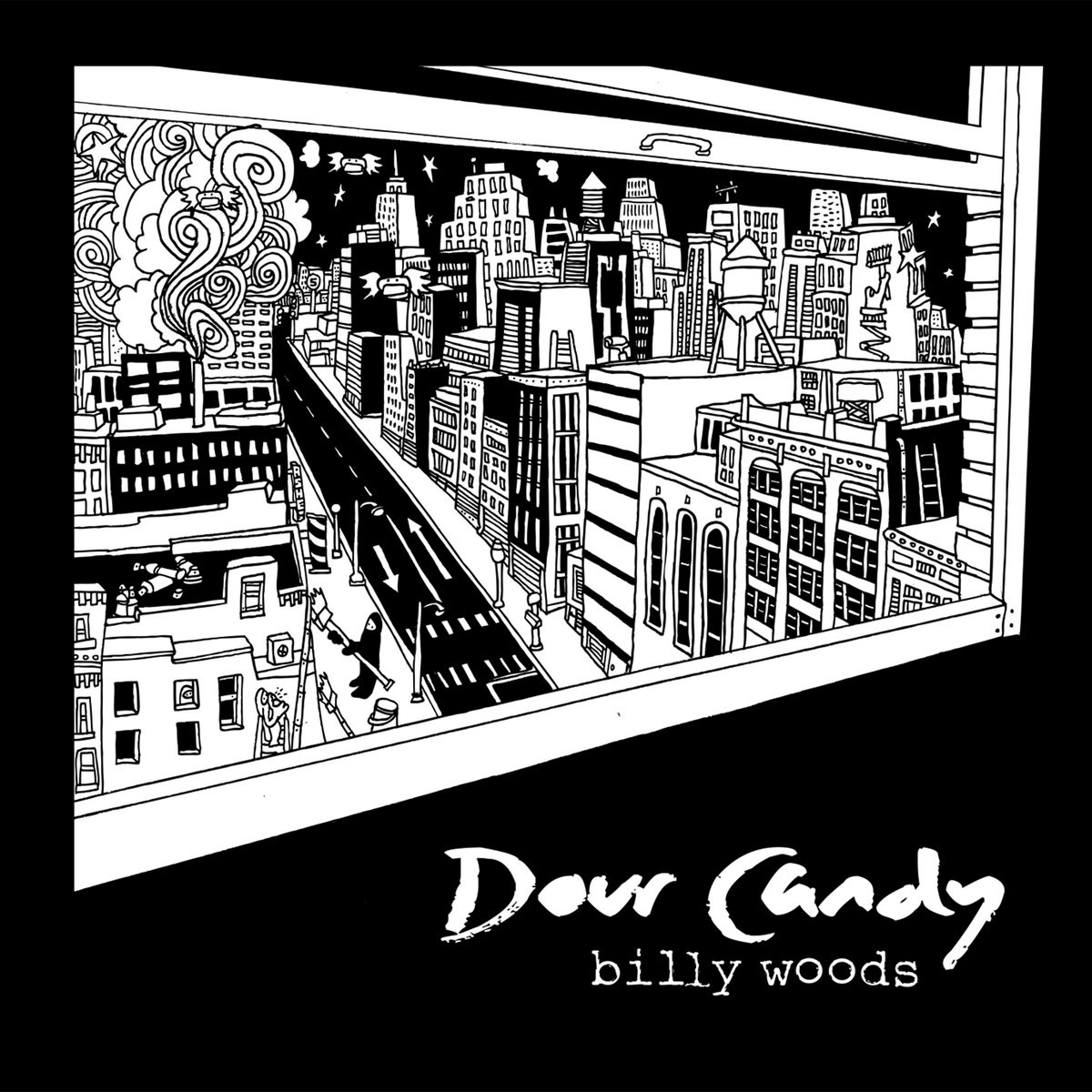

billy woods, Dour Candy

A year later woods teamed with Blockhead for a record that feels like a bar-stool confessional conducted under fluorescent hangover lighting: Blockhead’s dusty soul chops and detuned organs give the MC room to stretch sentences into fractal digressions, so a tale about Pan-African socialism can pivot mid-bar into a riff on pawn-shop sign-spinners without losing the beat. The interplay is surgical; woods leaves pockets of negative space that Blockhead promptly fills with worm-eaten guitar or spiraling vibraphone, creating a push-pull tension that makes every snare hit sound like a snapped rubber band on bare skin.

Armand Hammer, Race Music

When woods joined forces with ELUCID, the resulting duo exploded the reportage of History into a kaleidoscope of competing timelines. Race Music opens with “Hatchet Job,” where a broken-glass drum loop staggers under ELUCID’s cryptic sermon while woods maps public-housing elevators onto Middle-Passage cargo decks; from there the album ricochets through dub-soaked anti-gentrification blues (“Sunni’s Blues”) and noir jazz hallucinations (“Cloisters”), always anchored by bass frequencies that feel dredged from the East River at midnight.

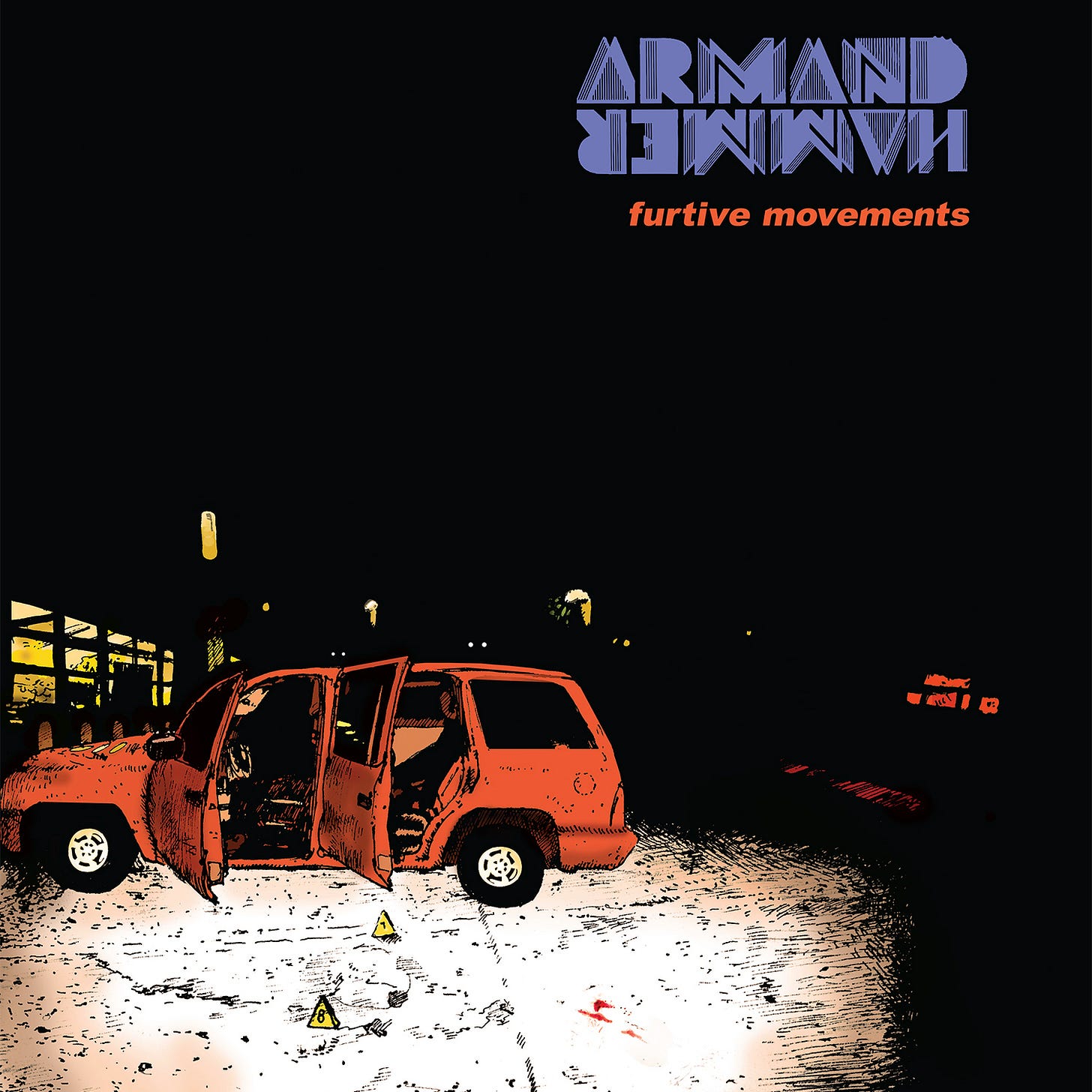

Armand Hammer, Furtive Movements (EP)

Clocking in at just over a half-hour in 2014, this EP tightens the duo’s lens without sacrificing its breadth: Blockhead, Messiah Musik, Steel Tipped Dove, and Von Pea supply beats that throb like surveillance hard drives, and woods and ELUCID trade verses dense enough to trigger metal detectors. The project’s lone outside voice, Curly Castro, arrives midway through “F.U.B.U.” to underline the EP’s preoccupation with ownership of land, of narrative, of cultural memory—and then vanishes, leaving echoing questions in his wake.

billy woods, Today, I Wrote Nothing

Borrowing its structural conceit from Daniil Kharms’ absurdist micro-fiction, woods carved twenty-four vignettes that stop, start, and pivot at will, each track barely long enough to set the scene before the next fragment barges in. The compressed format intensifies the prose: a single verse might juxtapose Staten Island ferry schedules with Angolan civil-war troop movements, then resolve in one stinging punchline, the musical equivalent of flash photography in a dark archive. Producers like Willie Green and Blockhead drop skeletal loops that vanish just as they start to feel familiar, mirroring the record’s themes of impermanence and chronic urban dislocation.

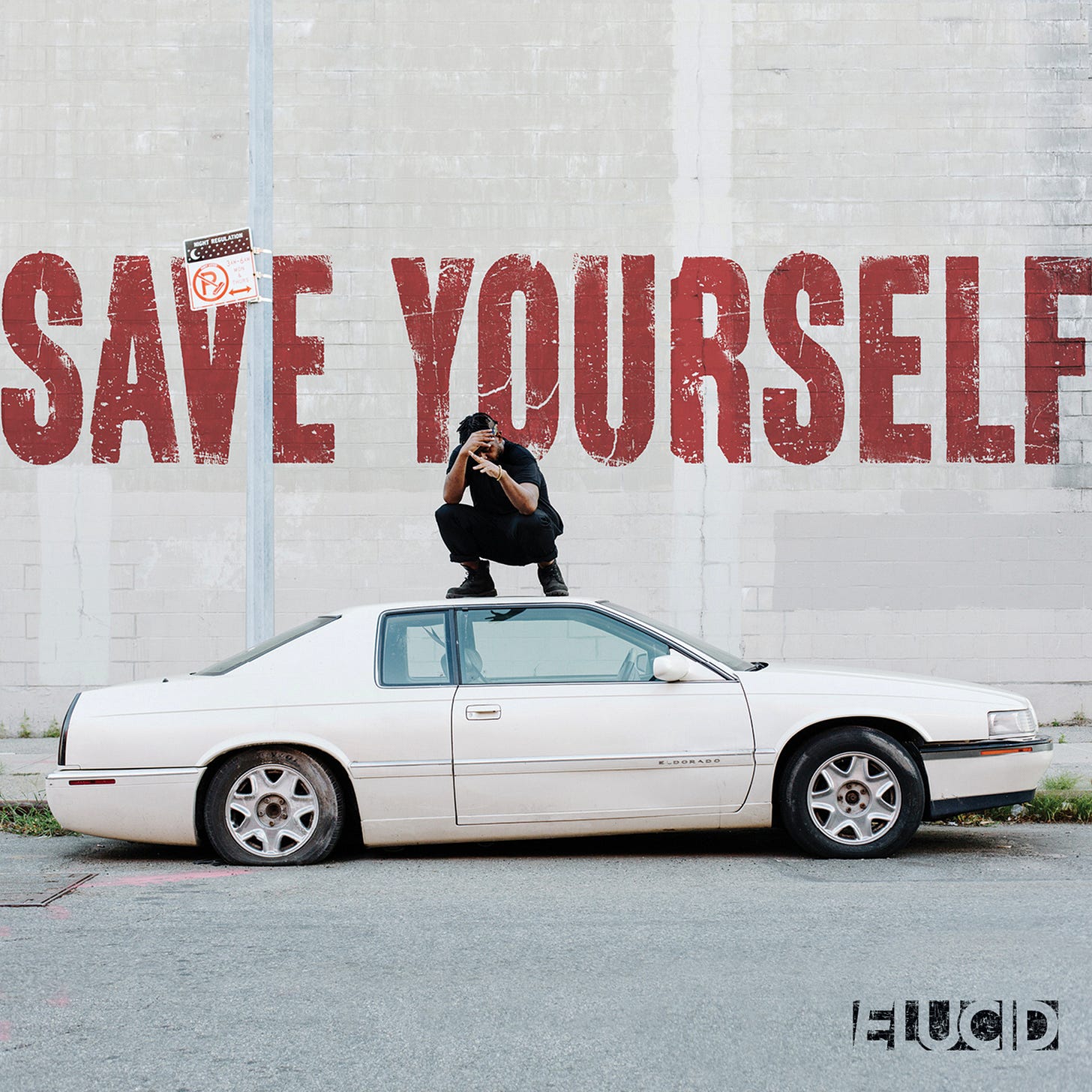

ELUCID, Save Yourself

Where woods often weaponizes history, ELUCID abstracts it, and his official outing floats like a fever dream in which church spirituals bleed into analogue synth squelches, free-jazz cymbal washes dissolve beneath trap-style hi-hats, and guest vocalist Psychic Twin hovers over the mix like radio static from an untraceable frequency. It reads as self-exorcism where parables about shapeshifting deities share breath with first-person laments about landlord court dates, yet the delivery stays incantatory rather than confessional, suggesting that transcendence might lurk inside the very systems designed to erase it.

Willie Green, Doc Savage

On his 2016 full-length, the Brooklyn producer stages a pulp-novel adventure inside the guts of an SP-404, assembling breakbeats that punch like comic-panel sound-effects and layering them with horn stabs, VHS synthesizer pads, and cameos from an underground super-team—Open Mike Eagle, Milo, billy woods, ELUCID—who treat each beat like a trapdoor into some alternate continuity. A twenty-page lyric book accompanied initial digital downloads, emphasizing the record’s commitment to world-building: every sample feels annotated, every drum fill cross-referenced, until the album functions as both mixtape and meta-text about the archivist impulse that animates Backwoodz as a whole.

ELUCID, Valley of Grace

The opener “Dromedary” plunges straight into tape-warble drones and distorted hand-drum loops, setting a woozy horizon where ELUCID stacks alliteration until consonants crumble into pure texture, then pivots into chant-like refrains that dissolve as quickly as they appear. Throughout the suite, a single synthesizer patch mutates from glassy arpeggio to sub-bass tremor, mirroring lyrics that slide from Harlem stoop memories to visions of desert asceticism with no pause for scene changes. The ten-minute closer “Noon Prayer” is built on a field-recording of church bells, wordless hums, and cracked-snare echoes; by the time the bells fade, the track has folded five drum patterns into one polyrhythmic tide, underscoring ELUCID’s thesis that spiritual experience can be pried from urban noise if you loop it long enough.

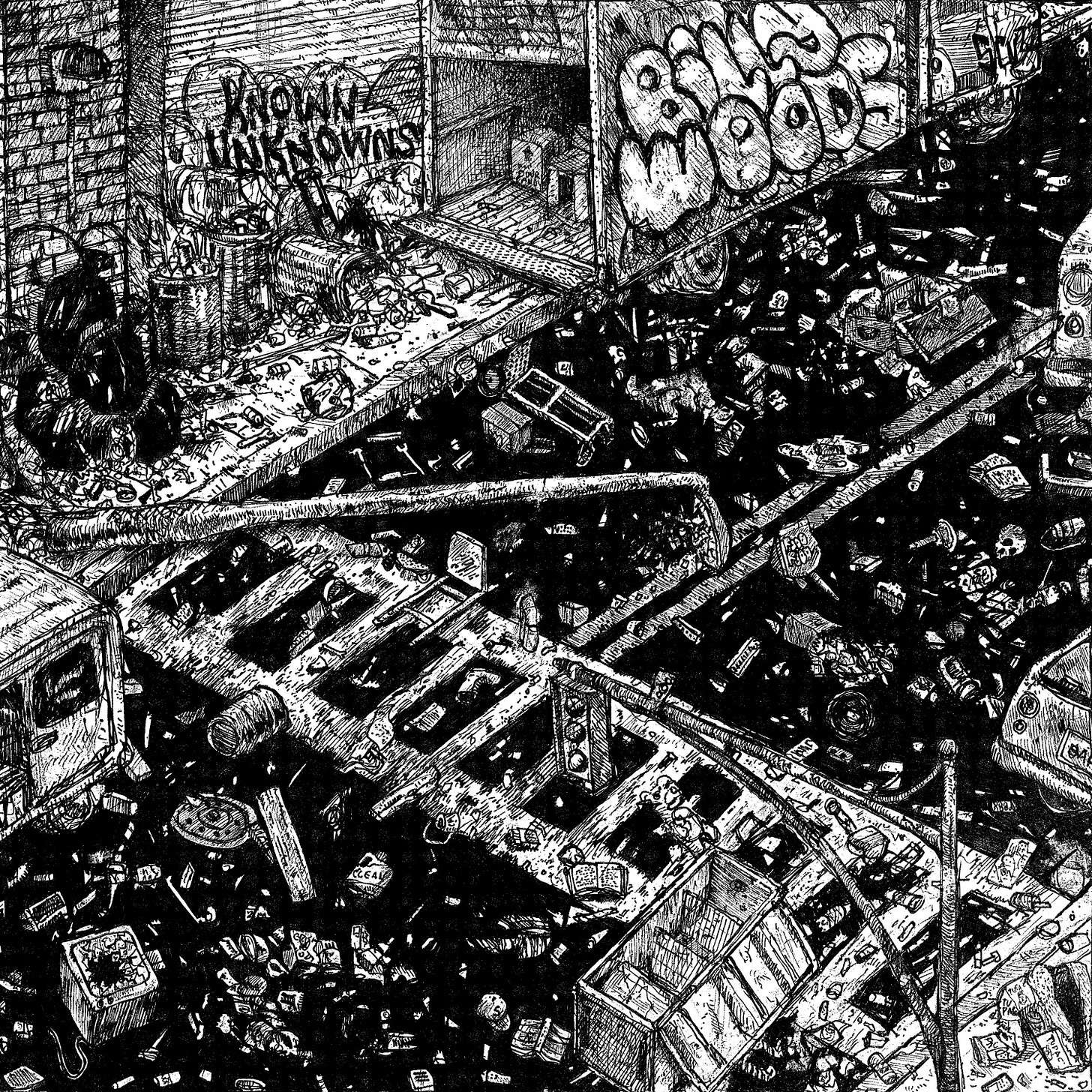

billy woods, Known Unknowns

Blockhead’s beats are deceptively warm here—vibraphones glimmer, filtered bass lines bump like vintage boom-bap—yet every comfort gets undercut by sudden dropouts that leave woods’ voice hanging over bare kick drums, forcing attention onto labyrinthine couplets about private-prison lobbyists, Zimbabwean childhood memories, and late-night car rides down Flatbush Avenue. The production list stretches beyond Blockhead to include contributions from Aesop Rock and others, and you can hear the hand-off: “Bush League” splatters dissonant organ stabs between each snare while “Superpredator” floats on haunted-house flute, letting woods shift from clipped reportage to sardonic half-singing without losing pocket. Homeboy Sandman’s grin slices through “Wonderful,” ELUCID’s cameo on “Nomento” turns the track into a back-and-forth treatise on rootlessness, and Aesop’s cameo on the opener feels less like star power and more like another scholar entering the roundtable.

Armand Hammer, Rome

Over a collage of dusty drums, cracked-vinyl choirs, and occasional blues-guitar snarls, ELUCID and woods trade verses that treat the ancient empire of the title as a metaphor for every crumbling super-power since—sometimes Rome is New York real-estate, sometimes it is post-colonial Africa, sometimes it is the listener’s own moral complacency. The beat on “Carnies” flips a carnival organ into something sinister, letting ELUCID describe doomsday cults while woods counters with anecdotes about cash-advance storefronts; elsewhere, “Dead Money” stretches a tremolo guitar and distant siren into an endless tension that never resolves, mirroring lyrics about economies built on perpetual crisis. Brief interludes, reminiscent of radio static, glue everything together, making the album feel like one long pirate-station broadcast from beneath the streets.

Armand Hammer, Paraffin

If Rome suggested an empire on fire, Paraffin sounds like sifting through the ashes: drums crackle as if recorded through burning tape, bass drops arrive late and leave scorch marks, and snippets of gospel vocals flicker like dying coals before being snuffed out by noise bursts. The pair tighten their spiral as shown on “Dettol,” where ELUCID loops images of kerosene baths and chemical disinfectants while woods ponders the price of clean water, both rappers rapping in clipped phrases that overlap like improvised harmony. “Ecomog” runs less than two minutes yet crams in references to West African peacekeeping forces, Reaganomics, and corner-store surveillance cameras; the brevity intensifies the record’s sense that catastrophe is best captured in fragments.

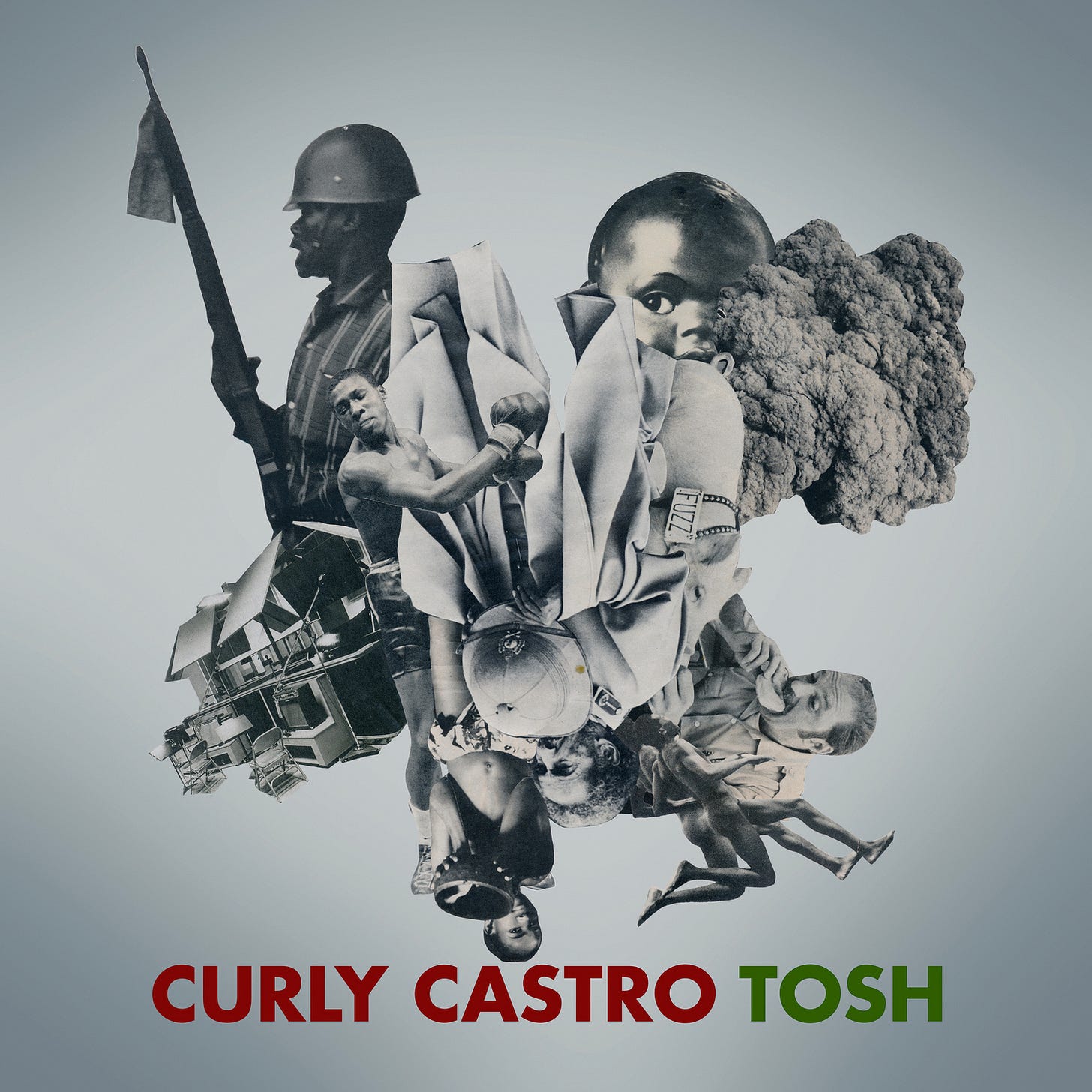

Curly Castro, Tosh

Curly Castro push through these tight cuts with a voice that mixes neighborhood slang and blunt political talk. The opener “Emory Dug” rides a clipped vocal sample and hard snares from ELUCID’s beat, setting an urgent pace, while Floodwatch’s heavier low-end on “Dark Skinned Drum” matches direct lines about color and power. “Walking Razor,” handled by Messiah Musik, flips a raw guitar lick into a stark loop that underscores Castro’s warning-tone storytelling, and a quick back-and-forth with Zilla Rocca on “Moshulu” keeps the energy high over gritty drums supplied by the Expert. Blockhead’s airy flute sample carries “Ital-You-Can-Eat,” inviting a sharp guest verse from billy woods, and later tracks move through Messiah Musik’s smoky keys on “Grandma’s Fable,” Small Professor’s punchy chops on “The Good Reverend Doctor,” and Uncommon NASA’s tense synths on “Night Terra Fabulous,” giving the record variety without drifting from its raw boom-bap core.

Blockhead, Free Sweatpants

Blockhead strings fourteen tracks into a loose-limbed panorama of dusty funk loops, warm Rhodes chords, and chopped vocal snippets that never fully resolve into hooks, keeping the ear drifting while guest MCs land surgical verses. Opener “Dream On” rides a glockenspiel motif that sparkles above sub-bass, setting a breezy tone that gets flipped on “Slippery Slope,” where billy woods, Open Mike Eagle, and Breezly Brewin volley absurdist boasts over stuttering drums that suddenly drop to half-time for eight bars before snapping back. Elsewhere, Aesop Rock’s cameo on “Kiss the Cook” slides over minor-key guitar chops, and Tree’s gravel tones on “Frank” sit atop a shuffling groove that feels like lost DJ Shadow, underscoring Blockhead’s knack for quilting disparate voices into one flowing beat tape.

billy woods & Kenny Segal, Hiding Places

Segal’s production builds labyrinths featuring warped piano loops fold over themselves, kick drums that land just off the grid, and stray field recordings—bird calls, metallic clangs, distant sirens—bleed into the mix, creating sonic cul-de-sacs that woods navigates like a weary surveyor taking notes in the dark. “Spongebob” flips an overdriven guitar figure into something mournful while woods unpacks medical-debt notices and family estrangements; “Big Fake Laugh” pivots on a detuned Rhodes chord that never resolves, mirroring punchlines that curdle as soon as they hit the air. Whiplash dynamics define the album: one moment airy jazz cymbals shimmer under a whispered verse, the next the beat caves in under sub-bass, mirroring lyrics about hiding from debt collectors, ICE raids, and one’s own reflection.

billy woods, Terror Management

Named after the psychological theory that humans construct culture to buffer death anxiety, the album burrows into mortality themes with beats that feel half-eroded by weather. The drums sound water-damaged, vocal samples flutter like torn newspaper, and sudden flute lines appear then vanish like hallucinations. On “Western Education Is Forbidden,” a swirling vocal loop frames verses about colonial language and forgotten ancestors, while “Long Grass” recruits Pink Siifu and AKAI SOLO for a round-robin of pastoral imagery poisoned by drought metaphors. The sequencing swings between fever-dream skits and full tracks, so the record feels like paging through a half-burned anthropology textbook, each charred corner revealing woods’ central question: what rituals survive when the empire that birthed them collapses.

ShrapKnel, Cobalt (EP)

Curly Castro and PremRock join forces over Messiah Musik’s rusted-metal drums and ELUCID’s jagged synth stabs, crafting a short project that punches like dented aluminum bats on cracked concrete. “Milk of the Poppy” marries industrial bass growls to snare rolls that stutter like jammed-up inkjet printers, while the MCs trade Cold-War spy jargon and NBA trash talk as though both belong to the same coded language. The centerpiece “Dagger & Cloak” slows the tempo until each kick lands like a footstep in an empty hallway, letting Castro’s grim one-liners ricochet off PremRock’s dense internal rhyme strings; the beat then flips midway into shimmering pads, suggesting momentary clarity before plunging back into murk. By the time closer “Static” fades in amplifier hiss, the EP has sketched a blueprint for collaborative menace: two voices circling each other over beats that sound equal parts scrap-yard percussion and ambient dread.

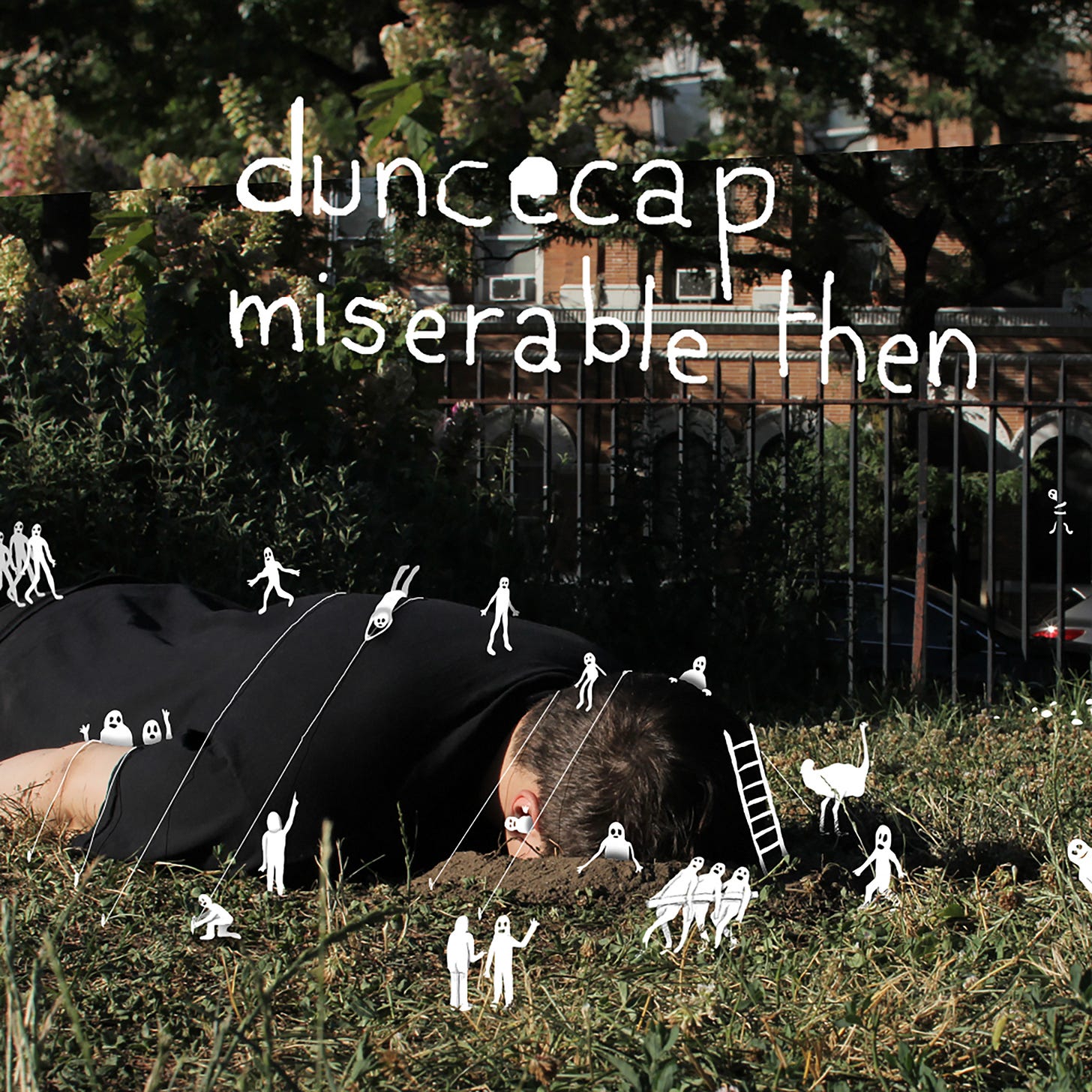

Duncecap, Miserable Then (EP)

Over ELUCID’s humid beds of reversed guitar, hissy Mellotron, and snare hits that sound like staplers popping, Duncecap trades his earlier prankster tone for weary street haiku, letting images of broken plate-glass and wilted deli roses unspool in breathless enjambment until each verse feels like a panic attack scribbled on butcher paper. His syllables stretch across the bar line, then double back in half-rhymes that scrape against the grain of the beat, mirroring the EP’s central tension between collapse and stubborn forward motion. Even the brief instrumental interludes matter: warped doo-wop croons melt into distant subway rumble, underscoring the record’s suggestion that nostalgia is just another form of corrosion.

ShrapKnel, ShrapKnel

Curly Castro and PremRock rap like two spies passing microfilm under a street lamp, finishing each other’s clauses in a clipped argot of Cold War code names, NBA trade rumors, and kitchen-sink surrealism, while ELUCID and Willie Green lace snares so over-compressed they clang like loose manhole covers. The mix is pocked with movie-theater foley—creaking door hinges, gun-cock echoes, rust-flecked pipes—that make every beat feel set inside an abandoned steel mill, and yet the hooks bloom in pockets of grim melody: cracked organ chords in “Ghostface Targaryen,” stray vibraphone plinks in “Red Bernie,” throat-sung vocal scratches in “Gun Metal Paint.” Across the runtime, the duo treats language like shrapnel itself, hurling jagged fragments that stick in the listener’s ear long after the drums fade.

ELUCID, Shit Don’t Rhyme No More

ELUCID sheds light on the hinges of traditional song form. Sonically, drums vanish mid-bar only to reappear in double-time, and vocal tracks multiply like phantom limbs, creating a vertigo that the MC navigates with spiraling internal rhymes and sudden choral chants in Igbo and Pentecostal call-and-response. Self-produced tracks transform detuned kalimba and blown-out bass into a lurching march, while guest beats incorporate fragments of harp, field-recorded rain, and tape rewinds that splinter the stereo image. The record’s closing suite layers distorted breathing, pitched-down sermon samples, and cymbal rushes beneath a verse that equates writer’s block with spiritual drought, making the very act of rapping sound like exorcism.

Armand Hammer, Shrines

The duo floods its already dense poetics with dream-logic collage on Shrines as woodwinds flutter over rim-shot loops just off-grid, sub-bass hums under field recordings of rustling leaves, and choruses dissolve into free-jazz horn squeals before a new drum break yanks the track somewhere else entirely. Features—from Pink Siifu murmuring through distortion to KeiyaA stacking gospel runs into minor-key dissonance—arrive like spirits at a séance, summoned then dismissed in the same bar, reinforcing the record’s fixation on impermanence as power. Throughout, ELUCID spits cubist image clusters about sugar-cane fires and overgrown lots, while billy woods anchors the blur with deadpan reportage on gentrification schemes and statue-toppling flashpoints; together they frame the city as a forest where every abandoned building hides a sacred relic if you know which wall to pry away.

Googie & Henry Canyons, Hijinx

Riding Henry Canyons’ dust-speckled boom-bap complete with upright-bass slides, muted trumpet loops, and rim clicks that swing like late-night jazz quartets—Googie unfurls long, conversational lines that drift from bodega small talk to metaphysical musings about reincarnation without ever losing the pocket. The production leans deceptively breezy, featuring vinyl pops and tape flutter, which gives the grooves a picnic-blanket warmth. Yet, each chorus sneaks in off-kilter chord shifts that tilt the mood from nostalgia to undertow. Halfway through, a surprise pedal-steel guitar solo cuts the haze, echoing the duo’s thesis that folk memory and hip-hop architecture can share the same frame without sanding off any edge.

Fielded, Demisexual Lovelace

Kristin Faye’s voice glides over liquid-crystal synth arpeggios and heartbeat sub-bass, bending notes in microtonal sighs that blur the boundary between R&B croon and avant-gospel ululation, all while lyrics peel back layers of intimacy, shame, consent, and after-shock tenderness with diaristic precision. The production laces distorted trap hats to lullaby piano, then drenches everything in cathedral reverb, creating a floating prism where each percussive hit blooms into pink noise and then collapses into silence. Interludes thread spoken-word confessionals through modular-synth squelch, presenting desire as both code to be hacked and ritual to be honored.

Moor Mother & billy woods, Brass

A swarm of detuned clarinets, distorted kettle drums, and crackling short-wave signals frames two voices moving in contrapuntal tension: Moor Mother shouts elliptical time-travel manifestos, woods replies with granular street detail, and the beats fracture under the weight of that dialogue, veering from doom-jazz dirges to industrial breakbeats that implode just as the groove locks in. Nowhere is the push-pull clearer than “Furies,” whose queasy synth drones suddenly open into melodic cello, as if a rusted factory wall slid aside to reveal stained-glass windows. The album’s final movement loops choral sighs beneath whispered asides about memory palaces and colonial cartography, letting the listener drift out on a frequency equal parts lament and rallying cry.

Armand Hammer & The Alchemist, Haram

Alchemist supplies pulverized soul samples and sub-bass pulses so low they rattle headphones, then leaves vast pockets of negative space into which ELUCID and woods pour riddles about ritual slaughter, smuggled antiquities, and the numbing pace of disaster; the resulting tension makes every drum hit feel like a floorboard giving way. Guest spots—from Earl Sweatshirt’s whispered insomnia to Quelle Chris’ carnival-barker sarcasm—arrive draped in echo, as if visiting from nightmares one block over. The closer glues spectral strings to a bass line that rises like floodwater, allowing both MCs to frame apocalypse not as event but as ambient condition through which love must still be negotiated.

PremRock, Load Bearing Crow’s Feet

PremRock leans into storyteller mode, his gruff cadence tumbling across jazz-rock drum loops where brushed snares and overdriven Rhodes spin like ceiling fans in a dive bar at closing time, while the hooks sneak in on distant guitar harmonics that recall late-night country radio leaking through city walls. Lyrics drift across sun-bleached parking lots, shuttered diners, and phantom limbs of friendships gone stale, stitching those images into a patchwork of acceptance that never slips into resignation. Sparse guest vocals include billy woods in a low, conspiratorial register, Fresh Kils chopping MPC pads into hiccupping fills—underline the record’s thesis that survival is measured not in victories but in how gracefully one carries accumulated fracture.

Curly Castro, Little Robert Hutton

Over a production palette that welds dusty Memphis horn samples to pounding breakbeats and serrated noise bursts, Castro delivers a whirlwind syllabus of radical history, peppering bars with footnotes to Bajan folklore, Black Panther communiqués, and speculative-fiction heat visions where drones patrol sugar-cane fields. His rhyme schemes flip between dancehall syncopation and East-Coast machine-gun cadences, often within the same line, mirroring the record’s restless jump-cuts from beachside childhood memory to militant street sermon. Mid-sequence, a beat built on hammered dulcimer and sub-aquatic bass drops out entirely, leaving Castro reciting names of martyrs over faint vinyl crackle—a moment that lands like a breath drawn before the next wave of percussion crashes in.

Steel Tipped Dove, Call Me When You’re Outside

The producer opens with vinyl hiss so thick it coats the hi-hats, then slips in a mournful clarinet figure that keeps bending out of tune before a kick drum finally lands like a manhole cover slamming shut. Guest MCs tumble through in quick cuts, but the star is negative space: whole bars where only sub-bass and tape flutter remain, forcing voices to sound as if they’re phoning from a pay-phone at dawn. A stray glockenspiel chime appears through “NFT,” bright for one bar before dying into an echo that never returns; that vanishing act becomes a motif, mirroring verses about friendships eroded by time more than violence.

Fielded, Young Medusa (EP)

Fielded drapes crystalline vocal runs over kick drums that pulse at resting-heart tempo, then feeds each note through delay so it smears into something half-prayer, half-AI-glitch. A spritz of modular synth chirps around “Damaged,” but beneath the shimmer lies an 808 that trembles like a swallowed sob, matching lyrics that catalogue soft trauma and pleasure rituals with equal tenderness. A covert Kate Bush interpolation surfaces in “Mother Stands for Comfort,” only to be shattered by gated reverb, suggesting that even inherited melodies must be broken open to reveal new marrow.

Defcee & Messiah Musik, Trapdoor

Messiah Musik lays iron-filings snares beneath underwater piano loops, then toggles time-signatures mid-verse so Defcee has to skid across bar lines like a parkour traceur leaping between rooftops. “Commute” curls a muted horn and strings while Defcee weighs surveillance-state dread against barbershop banter, proving that casual vernacular can house apocalyptic theory. Instead of hooks, the record uses tape-rewind whooshes to signal movement, lending the impression of rummaging through a redacted archive whose blacked-out passages still hum beneath the ink.

Hajino & Duncecap, Go Climb a Tree

Hajino welds toy-keyboard bloops to breakbeats clipped so sharply they click like cicadas, giving Duncecap a carnival tightrope on which to balance deadpan anxieties and sudden flecks of absurdist joy. Guests drift through like wind-chimes—Quelle Chris snarls a twelve-bar cameo, AKAI SOLO drizzles stream-of-consciousness non-sequiturs—yet every voice seems taped to the same branch, swaying in unison when a sub-bass gust arrives. The closing track lets bird-calls and nylon-string guitar twinkle beneath whispered ad-libs, hinting that escape might be found not in flight but in perched observation.

billy woods, Aethiopes

Preservation’s palette stacks Satie-like piano clusters beside Anatolian psych-guitar and Ethiopian krar plucks, then dusts the fusion with vinyl static until the global reference points blur into one haunted diasporic hum. billy woods threads through that fabric with couplets that splice Congo rubber exports to Bed-Stuy brownstone mortgages, never pausing for a full stop so the flow feels like a customs form scribbled while sprinting through arrivals. Moments of near-beauty—an airy flute trill here, a jazz ride-cymbal sparkle there—always buckle under gnarled bass, echoing woods’ assertion that grace is fleeting but the ledger of violence is permanent.

ELUCID, I Told Bessie

Built as a love-letter and séance for the grandmother who first sheltered his bedroom demos, the album opens with distorted humming that slowly pans across channels like someone pacing the apartment floor above. Beats swap out meter every few bars, one moment breakneck footwork syncopation, the next a dirge-slow gospel loop, yet ELUCID’s multitracked chants knit them together, invoking ancestral memory as both shield and scalpel. A children’s choir sample that Child Actor produced sneaks into “Old Magic,” then pitch-slides into demonic register, reinforcing lyrics that insist memory is never static but rather a reel of film left too close to the radiator.

ShrapKnel, Metal Lung

Messiah Musik’s drums thunder like sheet-metal being sheared, while ELUCID sprinkles synthesizer shards that ping-pong across the stereo field, letting Curly Castro and PremRock volley quantum-spycraft metaphors until syllables collide and spark. A wheezing accordion loop under “A Tribe All Stressed” sounds like a circus gone rancid, an ideal backdrop for Castro’s patois-laced invective and PremRock’s noir monologue about snipers on water towers. Even the sparse interludes matter: amplifier hiss, Geiger-counter ticks, and reversed cymbal swells sketch a radiograph of the duo’s shared lung after years of inhaling smog-thick rap detritus.

AKAI SOLO, Body Feeling (EP)

Beats glimmer with muted kalimba and soft-focus synth, then fracture into grainy boom-bap once the Brooklyn MC begins plaiting internal rhymes dense enough to feel like braided muscle fibe. “Just Us” rides a soul-brush shuffle that ducks under stretched vocal-sample moans, leaving just enough oxygen for AKAI to ponder dopamine loops and root-chakra imbalances. The EP’s coda, “Yes!,” strips everything down to only a sample loop, suggesting that embodiment sometimes requires turning the volume so low you can hear your own tendon creak.

billy woods, Church

Messiah Musik drapes trembling organ and crackling choir fragments over kicks that strike like gavel blows, and woods narrates nocturnal rituals—rolling papers on pew benches, cryptic confessions in corner-store parking lots—until the sacred and profane overlap like double-exposed film. On “Fever Grass,” a muted trumpet whines behind a verse linking Caribbean herbal remedies to D-Train tracks, then the horns collapse into silence, replaced by tape rewind that drags the whole mix backwards three seconds, forcing woods to rap the final bar a second time as if doomed to perpetual repentance. When a fragile gospel chord finally glows beneath the closing fade-out, it feels earned, not redemptive but resolute: the sermon ends, the doors unlock, the night outside still smells like wet concrete and diesel.

AKAI SOLO, Spirit Roaming

A flood of detuned kalimba and grainy sub-bass opens the door, then AKAI SOLO strides in splicing anime reference and spiritual koan without pausing to draw breath; “Cudi” erupts in clipped hi-hat clusters that stutter like cassette teeth chomping a ribbon, while “Mob Psycho 100” sinks a murky Rhodes chord beneath a low-pass filter so thick it feels like wading through fog. Mid-sequence, “S.O.M.” lets a Pepper Adams sax sample circle the snare hits, giving AKAI space to braid internal rhymes until a single line arcs from Crown Heights block parties to astral-plane way-stations, and the momentum never slackens because each short track ends by smashing head-first into the next, mirroring the roam-with-no-map thesis implied by the title. When Armand Hammer materializes on “Upper Room,” their overlapping baritone and tenor tones refract the beat’s spectral choir into three separate dimensions, underscoring the album’s insistence that communion is a sonic practice, not a genre tag.

Jeff Markey, Sports & Leisure

The record clicks on with the sneaker-squeak of “Island Time-Lapse,” a sixty-second loop that places vinyl hiss over chopped vibraphone before a muted kick locks the groove; from there Markey parades one vignette after another—“90’s Dunks On VHS” chops Boards-of-Canada-style pads into a lopsided boom-bap shuffle, “Mo Lava” filters steel-drum hits until they crumble like shelled concrete, and “Floaters” invites billy woods to spill elliptical trash-talk over strings warped to carnival pitch. Voices arrive like courtside hecklers—PremRock trading quips on “Tasted Ink,” Defcee and Fatboi Sharif volleying insider jokes on “Pryor and Wilder”—yet the producer’s crate-dust warmth ties everything together, and instrumental reprises on the cassette B-side flip earlier tracks inside out, turning rhyme-spaces into negative-space beat studies.

Skech185 & Jeff Markey, He Left Nothing for the Swim Back

After the opening title cut, “Badly Drawn Hero” drags splintered guitar through gated reverb while Skech185 launches a triple-time flow that ricochets between Chicago alleyway lore and Afrofuturist nightmare with no scenic stopovers; Markey meets that intensity by pitching cymbal crashes down a semitone so every impact sounds like metal crumpling in slow motion. “East Side Summer” cools the tempo just enough to squeeze in a swinging upright-bass line, then spikes the mood with clipped gospel handclaps that disappear the instant a new tangent begins, capturing the emcee’s refusal to romanticise nostalgia even as he excavates it. The two-part of “Western Automatic Music” finishes the album by funneling radio-static sweeps beneath ragged string pads while Skech185 lists names of those swallowed by undertow, literal and metaphorical, until the fade-out feels like a shoreline swallowed by night.

Backwoodz Studioz, High Bias

The compilation kicks off with “Which Way Is Up,” a brief cyclone of distorted synth stabs and rapid-fire couplets that sets the mixtape’s guiding principle: splice first, categorise never. Moments later, Fatboi Sharif’s “Carousel” drops a throbbing bass drone beneath pinched-voice cadences that twist childhood fair-ride imagery into body-horror parable, and ShrapKnel’s “Slick Watts” follows by layering Kenny Segal’s brushed-snare jazz shuffle under three overlapping voices until punch-ins blur into crowd chatter. Elsewhere, ELUCID turns “Stocking Caps” into a noir monologue over Sebb Bash’s reversed-vocal tapestry, and Cavalier floats through “Meta” on vapor-trail chords that collapse into glitchy rim-shot eruptions, reinforcing the tape’s collage logic where it functions as field report, rough mix, and communal Rorschach all at once.

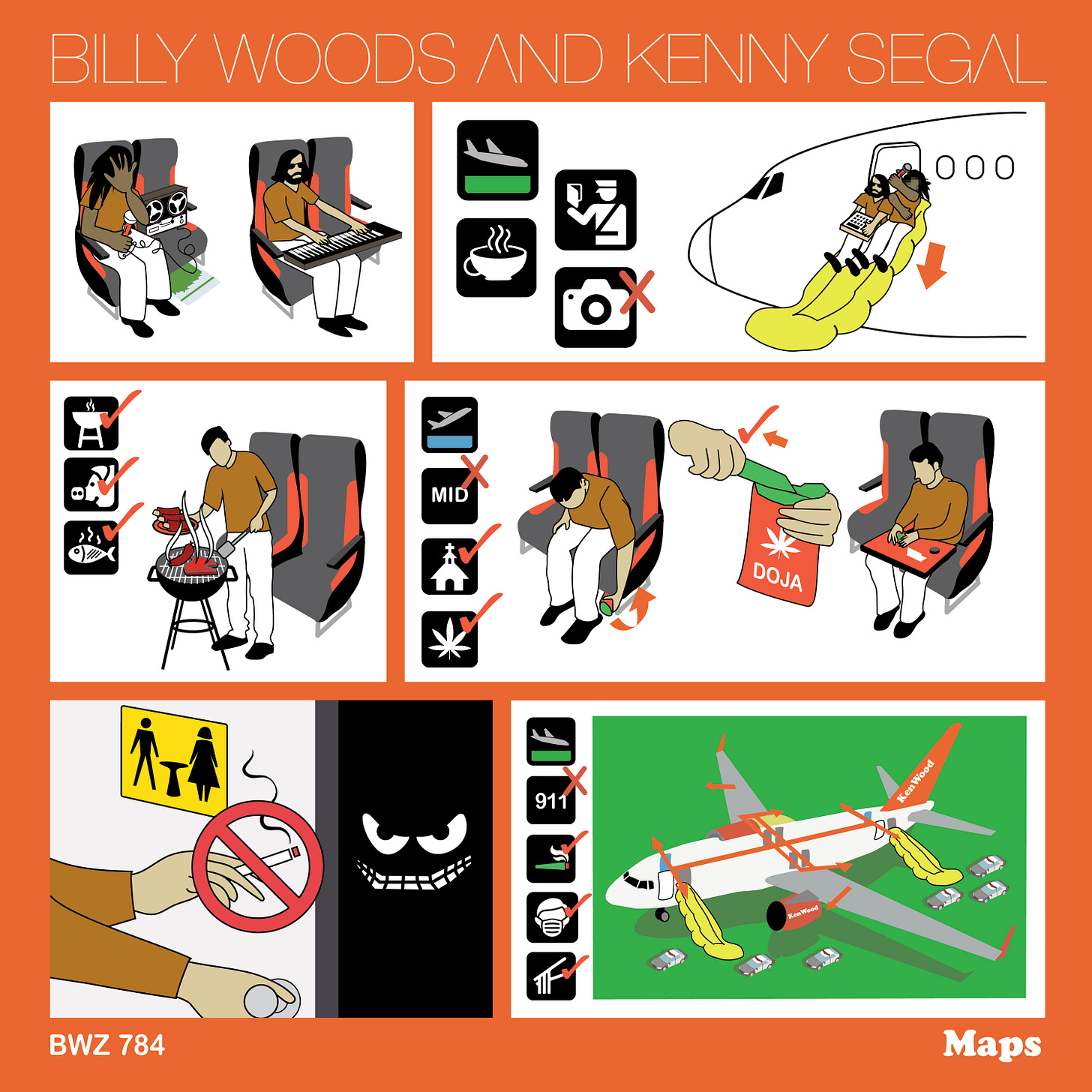

billy woods & Kenny Segal, Maps

A shortwave hiss gives way to the sputtering engine of “Kenwood Speakers,” where woods murmurs a travelogue of motel-TV limbo over Kenny Segal’s synths that pulse like malfunctioning dashboard lights; “Soft Landing” follows with brushed ride cymbal and nylon-string guitar so gentle it feels sarcastic once the narrative shifts to TSA pat-downs and dissipated per-diem. This mirrors an endless tour itinerary. After the swaggering “Rapper Weed” lulls into contact-high languor, “Year Zero” detonates with a Danny Brown cameo that slices through Segal’s tectonic bass drop like cracked carnival glass, and the aftershock resonates into “Hangman,” where a single piano note tolls beneath woods’ admission that transit grants escape but never absolution.

Fatboi Sharif & Steel Tipped Dove, Decay

“Phantasm” enters on woozy woodwind glissandi and a heartbeat kick, Sharif’s pitch-bent delivery curling around words until syllables melt into onomatopoeia; Dove counters by boosting the mid-range grit so high the drums rasp like rotted speaker cones. Severally subsequent track feels shorter and more claustrophobic—“Designer Drugs” lurches on a carnival-organ loop that drops one note early every fourth bar, distorting the listener’s internal clock, and “Dimethyltryptamine” chews its own snare tail with reverse-reverb so it sounds like a zipper ripping open a dreamscape. By the time “Prisoner of Jesus” drifts in on Gregorian-chant shards, the album has reduced time to a strobing series of jump-cuts, mirroring its lyrical obsession with psychedelic dislocation and spiritual corrosion.

Fielded, Plus One

Wind-chime synth arpeggios dance around heartbeat bass on “Windbreaker,” where Fielded’s multi-tracked harmonies stack until vowel sounds blur into choir-pad texture and billy woods sneaks a sotto-voce verse through the seams. “Afternoon Sun” drips muted trumpet over back-masked percussion, letting Felicia Douglass’ honeyed alto hover like lens flare across the beat, while “Honeysuckle” jolts the flow with a Fatboi Sharif cameo whose gravel tone scratches against Fielded’s glasslike head-voice, casting desire as an allergic reaction. The record’s genius lies in its arrangement: each duet treats the guest not as a feature but as a mirror, bending Fielded’s exploration of consent, embodiment, and limerence back toward her own shimmering melodies.

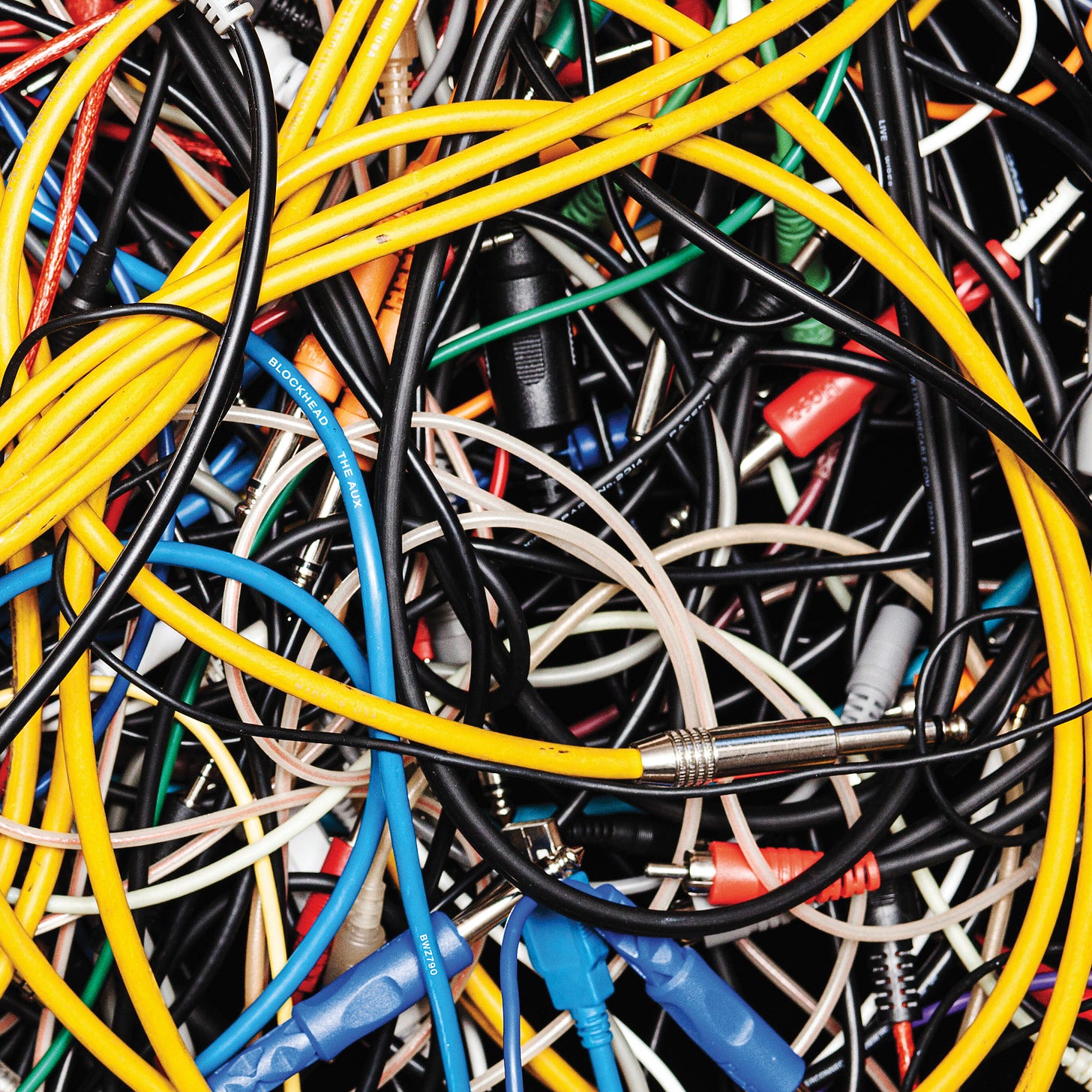

Blockhead, The Aux

A shower of jazz introduces “AAU Tournaments,” but just as the melody suggests innocence, billy woods and Navy Blue cut through with cynic’s swagger, and Blockhead dims the lights by side-chaining the bass until the mix inhales and exhales like an anxious lung. “The Cella Dwellas Knew” chops airy vocals and pianos into rhythmic punctuation under Quelle Chris’ sardonic imagery, while “Mississippi” slithers across the track that Aesop Rock crowds with alligator-jaw wordplay, turning the track into cracked southern-gothic road signage. Almost through the mid-album, “Lighthouse” strips down to lo-fi hi-hat and muted bass, leaving UGLYFRANK’s verse suspended like a bulb over open water before Blockhead detonates the rhythm section in double-time breakbeats, reminding listeners that calm is always provisional.

Cavalier, Different Type Time

A soft chorus of thumb-piano and faint surf noise opens the title track, and Cavalier glides across the pulse with meditative baritone, folding Brooklyn stoops, New Orleans second-line horns, and Oakland sunsets into one continuous panorama; each image lingers because Child Actor’s production leaves pockets of negative space where brushed snare or nylon-string guitar flicker then vanish. “Custard Spoon” pumps warm upright-bass beneath muted vibraphone, coaxing supple double-time cadences that bend meditation into kinetic release, and “Can’t Leave It Alone” diffuses into dream-sequence falsetto refrains before a single sub-bass swell snaps the daydream shut, underscoring the album’s thesis that deliberate slowness can still bruise.

ShrapKnel, Nobody Planning to Leave

Controller 7 flips scrap-yard percussion—rusted brake-rotor clang, chain-drag shuffle—into the backbone of “Metallo,” and Curly Castro laces Cold-War lingo around PremRock’s noir monologue until the beat’s industrial pulse sounds like spy-code in Morse. “Dadaism 3” invites Open Mike Eagle to pepper the groove with non-sequitur levity, but the hook caves in under distorted 808 splashes, emphasising the EP’s central friction between gallows humour and existential dread. On “Steel Pan Labyrinth,” a tape-warped pan line spirals beneath glitching snare rushes, and Onry Ozzborn’s cameo spreads out like ink in rainwater, staining the track with unresolved paranoia that lingers through the final fade.

ØKSE, ØKSE

“Skopje” staggers in on rolling floor-tom thunder and Savannah Harris’ cymbal scrapes, its pulse already fraying before ELUCID’s voice enters like a street preacher muttering futurist scripture, while Mette Rasmussen’s alto sax writhes around the cadence as if trying to saw through the bar lines. From there, Petter Eldh’s rubbery synth-bass and Val Jeanty’s granular electronics warp the shape of every phrase, so that on “Three Headed Axe,” drum accents drop half a beat late, forcing the horn to gasp for air and making the track feel simultaneously airborne and underwater. When billy woods turns up on “Amager,” his clipped couplets about colonial sugar routes skid across brush-stroke snare ghosts, and the contrast between his gravel timbre and Rasmussen’s piercing upper register casts the whole performance as foreboding call-and-response rather than conventional verse. Even the closing meditation, “Onwards (Keep Going)”, refuses release, stretching bowed-bass drones into nearly seven minutes of unresolved cadence, proof that this quartet treats tension as a destination, not an obstacle.

PremRock & Willie Green, Through Lines (EP)

The EP opens with “Imposter Syndrome,” Willie Green pitching a Rhodes chord down into molasses before letting a ride-cymbal fizz drift across the stereo field, and PremRock answers with densely nested internal rhymes that flip therapy jargon into self-deprecating stand-up, turning vulnerability into swagger without ever masking the bruise. “Call Abandonment Rate” invites Curly Castro and Defcee to volley back-office horror stories over a bass line that warps one cent sharp every bar, making the groove quiver like fluorescents about to blow, while Green sneaks quiet hand-clap ghosts behind the snare to keep momentum lurching rather than sprinting. “Pink Cloud” ends on a two-minute drift of reversed guitar picks and half-whispered affirmations, and the track’s unresolved loop feels like a notebook margin left blank for tomorrow’s revision, matching the record’s thesis that self-improvement rarely comes with clean punctuation.

Cavalier & Child Actor, Cine

Cavalier and Child Actor really does play like a film reel. “Sojourn” sets the scene with bongos, unorthodox samples, and bars that fold Brooklyn jitneys into New Orleans riverboats without a single cut, then “Dassit” flips the groove into a minor-key head-nod where half-quantized drums dissolve so thick it feels like projecting smoke across the stereo field. The record’s centrepiece “Moonlight Crush,” with ELUCID and Quelle Chris blurring in and out of the frame, and when the beat re-enters for “Knight of the East,” the sample slaps like a clapperboard, confirming the LP’s premise that memory is just jump-cut after jump-cut until it resolves in the brief dream-sequence “Gifted & Talented.”

Kenny Segal & K-the-I???, Genuine Dexterity

K-the-I??? darting between falsetto yelps and gruff mid-range as if voicing multiple radio operators fighting for frequency on “Ionosphere” that jolts awake with fidget-spinner hi-hats and wobbling Moog bass, while Segal sprinkles glassy synth pings that vanish the instant they catch the ear. Armand Hammer storms “Spellcasted Television” and the trio stacks image upon image—faulty cathode ray guns, climate refugees, late-night public-access static—until the hookless structure feels like a closed-captioning feed gone rogue. “Crushed Heavenly” folds ShrapKnel, PremRock, and Curly Castro around a drum loop that stutters with a weird jazz flip, turning cypher camaraderie into collective vertigo, then Segal follows a couple records later with “Season of the Sickness,” letting a single dulcimer figure decay beneath Fatboi Sharif’s guttural rasp, embodying the album’s fascination with entropy dressed as exuberance.

doseone & Steel Tipped Dove, All Portrait, No Chorus

“That Work” arrives on airy pads and sub-bass tremor, doseone bending vowels until they become percussive clicks that dance around Dove’s fractured snare placement, setting a rule that nothing will resolve where expected. “Went Off” features Open Mike Eagle gliding in with melodic deadpan just as Dove drops the low end to silence, forcing the guest to rap into an echo chamber, then slamming the beat back in with a sideways horn stab that feels like jump-cut editing in audio form. The highlight “Wasteland Embrace” partners doseone’s head-rush syllable pile-ups with billy woods’ deliberate crawl over a drone that morphs from organ sustain to distorted guitars and the song’s final thirty seconds strip everything but tape hiss and breath, nodding to the album title by leaving only portrait and no chorus in the empty frame.

PremRock, Did You Enjoy Your Time Here…?

PremRock details his rhymes in the liminal glow of airport lounges and motel televisions. “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” pairs ELUCID’s dusty drum shuffle with a clipped synth melody that climbs one note each measure, Prem unspooling anecdotes about hospice hallways and bar-back shifts, proving that reportage and reverie share common blood when filtered through the same grainy preamp. The album then ricochets: YUNGMORPHEUS flips a piano sample into woozy neck-snap on “Doubt Mountain,” Blockhead folds a jazz sample into vinyl rumble for “Flight Risk,” and Sebb Bash milks dusty pads until they distort under AJ Suede and Curly Castro’s tag-team on “Aim’s True,” yet Willie Green’s mastering glues each transition so tight that the whole sequence feels like one breath with multiple heartbeats.

billy woods, Golliwog

billy woods latest effort is a masterpiece. “Jumpscare” kicks off with scraping string harmonics and a single bass drum that lands like a body dropped down a stairwell, the woods diving straight into imagery of state violence and folk-horror dolls, his cadence clipped yet eerily calm against Steel Tipped Dove’s detuned piano cluster. “BLK XMAS” twists sleigh-bell jingle into minor-key unease while Bruiser Wolf slips carnival-barker punchlines between woods’ grim parables, the tension heightened by a drum pattern that refuses backbeat until the final bar snaps like a mousetrap. Throughout the record producers as varied as The Alchemist, Preservation, and EL-P scatter sonic debris—sampled screams, bowed cymbal drones, glitched sax reverb—yet woods threads them with a narrative that treats horror tropes as magnifying glass for systemic cruelty, so by the time the album ends, it fades into layered instrumentation by Human Error Club that the listener feels both exorcised and indicted.