The Handguide to J. Cole

From Fayetteville dorm rooms to platinum plaques. The mixtapes that built his name. The albums that tested his audience. A complete guide to J. Cole’s catalog before The Fall-Off closes the book.

The arc bends toward conclusion. When Cole announced that The Fall-Off would be his final album, he drew a line under a career that had spanned nearly two decades of mixtapes, studio records, and the persistent question of where exactly he belonged in hip-hop’s hierarchy. Some placed him among the greats. Others found his music competent but unremarkable, technically proficient without the spark that separates good from legendary. The debate itself became part of his legacy, a conversation that refused resolution no matter how many platinum plaques accumulated.

His story began in the mid-aughts, when a biracial kid from Fayetteville started uploading tracks to internet forums, chasing a dream that felt distant and improbable. It would end, supposedly, with a record designed to close the chapter he had opened all those years ago. Between those points stretched a catalog that documented one man’s attempt to reconcile commercial ambition with artistic credibility, mainstream success with underground respect, the desire to be beloved with the need to be taken seriously.

What follows traces that catalog from its earliest stirrings to its most recent complications. The mixtapes that built his name. The albums that tested his audience. The EPs that recalibrated expectations. The surprise drops that complicated his legacy. Each entry reconstructs the circumstances surrounding its creation and reception, placing these recordings within the broader context of Cole’s evolving career and hip-hop’s shifting terrain.

Full disclosure: This handguide was written before J. Cole surprise-dropped Birthday Blizzard ‘26.

The Come Up Mixtape, Vol. 1 (2007)

Jermaine Lamarr Cole had been uploading songs to internet forums for years under the name Therapist when he assembled his first official project, a mixtape hosted by DJ OnPoint and born from the rooms of St. John’s University dormitories in Queens and the cramped apartments of his mother’s Fayetteville, North Carolina neighborhood. Born in Frankfurt, Germany, to a Black American father serving in the military and a white mother, Cole had bounced between worlds his entire adolescence, and that displacement surfaced throughout The Come Up as both subject matter and stylistic restlessness. He self-produced twelve of the twenty-one tracks, including his debut single “Simba,” for which he shot his first music video.

The remaining productions borrowed from rap’s recent past, Cole rapping over instrumentals by Large Professor, Kanye West, Just Blaze, Salaam Remi, Mathmatics, and Ski. These choices signaled his allegiances clearly. He wanted to be heard in the lineage of Nas and JAY-Z, not the ringtone rappers dominating radio. Guest appearances from Deacon and Nervous Reck filled out the roster, though Cole commanded the vast majority of microphone time himself. That same year, he famously waited three hours in the rain outside JAY-Z’s Roc the Mic Studios hoping to hand him a CD of beats for American Gangster. JAY declined the demo, but Cole repurposed those productions for his own debut.

Production leaned on dusty soul loops and piano progressions that recalled mid-nineties New York street rap, the sort of sample-heavy construction that had fallen out of fashion during the ringtone era’s synthetic dominance. Cole spat over these beds with a nasally, almost boyish delivery, enunciating his words with deliberate precision rather than the slurred cadences that Southern trap had popularized. His flows shifted tempo within single verses, accelerating through complex syllable clusters before settling into melodic half-sung passages.

The mixtape spread across rap blogs during a period when the mixtape circuit had begun supplanting traditional A&R as the industry’s primary discovery mechanism, and Cole’s dense internal rhyme patterns and throwback boom-bap sensibilities drew notice from a small but attentive audience. DatPiff logged over five hundred thousand downloads eventually. The Come Up established his fundamental approach: he would be a rapper’s rapper who also wanted pop radio, a backpacker who craved mainstream validation, a college student making music for people who never enrolled.

The Warm Up (2009)

Roc Nation needed a flagship artist. When JAY-Z launched his imprint, he signed Cole as its first act, a bet on potential that the young rapper now had to justify. The Warm Up abandoned the lo-fi bedroom aesthetic of its predecessor for polished, sample-cleared productions that could have slotted comfortably onto major-label releases. “Lights Please” and “Dead Presidents II” showed that Cole’s technical abilities transferred cleanly to bigger budgets, his layered rhyme schemes now cushioned by crisp drums and warm, expensive-sounding keyboards.

Several songs registered with urban radio programmers who rarely bothered with free releases, an unusual penetration for mixtape material during a period when the format still functioned primarily as industry demo tape. The project moved Cole from internet curiosity to genuine prospect, drawing attention from hip-hop’s elder statesmen and younger peers alike. Features with Omen and other regional artists placed him within a loose collective of similarly minded lyricists pushing against Auto-Tune’s stranglehold on rap radio.

Cole handled most of the production himself, revealing a second creative dimension that would distinguish his catalog from contemporaries who relied exclusively on beatmakers. His drums punched with boom-bap weight while his melodic choices drew from Motown and Philadelphia soul traditions, creating a hybrid that honored East Coast lineage without fully abandoning Southern warmth. Synths surfaced sparingly, more accent than foundation. His arrangements left negative space where other producers would have stacked elements.

The mixtape moved through hip-hop’s transitional phase between blog era and streaming dominance, catching audiences who still downloaded files and burned CDs but who had begun migrating toward playlist culture. Cole would benefit enormously from this timing. His rise coincided precisely with infrastructure changes that allowed independent releases to generate the same cultural velocity as label-backed projects.

Friday Night Lights (2010)

The debut album kept slipping. His label deal remained intact, his JAY-Z cosign still carried weight, yet the retail release had stalled in development while Drake, Kid Cudi, and Nicki Minaj all capitalized on similar momentum to achieve multiplatinum success. Friday Night Lights landed as both creative statement and strategic intervention, a free release so accomplished that it forced Roc Nation to accelerate their timeline. Cole titled the project after the beloved television drama about Texas high school football, borrowing its themes of small-town aspiration and bittersweet coming-of-age to frame his own narratives of ambition and doubt. The mixtape was originally going to be called Villematic.

Most of these songs were slated for Cole World at some point, but when the label balked at the material’s commercial viability, Cole packaged them as a mixtape and started over on the album. Only “In the Morning” featuring Drake survived into the final retail tracklist. That collaboration became one of Friday Night Lights’ signature moments, Drake’s unexpected guest verse arriving after Cole had revamped a bedroom recording he’d made years earlier. “Villematic” repurposed Kanye West’s “Devil in a New Dress” instrumental, Cole stacking dense rhyme patterns over Bink!’s production while the original’s orchestral soul swelled beneath him. “Too Deep for the Intro” opened the project with confessional urgency. “Before I’m Gone” and “Premeditated Murder” balanced introspection with technical display.

Instrumentation drew heavily from soul and R&B catalog material, with Cole chopping vocal samples into new configurations rather than simply looping them beneath his verses. “Farewell” flipped OutKast’s “So Fresh, So Clean.” “See World” built on Earl Klugh’s “Living Inside Your Love.” “You Got It” featuring Wale interpolated Biggie’s “Hypnotize” over a Janelle Monáe sample. Drums hit with papery warmth, their transients softened by analog-style processing that evoked vintage equipment even when produced digitally. Pianos cascaded through minor progressions. Strings swelled and receded. The timbres evoked autumn specifically, something in their amber warmth and cooling registers.

Friday Night Lights won Best Mixtape of the Year at the 2011 BET Hip Hop Awards and proved that Cole could command attention without label machinery, that his audience had grown large enough to support independent releases with commercial-scale impact. The project downloaded over a million times within its first month, numbers that rivaled proper retail albums from established artists. His debut could no longer be delayed.

Any Given Sunday, Vol. 1 (2011)

In the months preceding Cole World, Cole released material at a rapid pace. He promised to return every Sunday until the album dropped, and he kept his word. The first Any Given Sunday installment arrived at the end of July with a young Michael Jordan gracing the cover, five tracks mixing new material with previously released freestyles. “Like a Star” was supposed to be saved for the second album, but circumstances forced Cole’s hand. “Knock On Wood” resurfaced as one of his favorite freestyles, a reminder for longtime followers and an introduction for newer converts. “Pity” paired him with Omen and Voli over Voli’s production, the Dreamville collective taking shape in real time. “How High” had been guaranteed a spot on Cole World at one point before plans shifted. The series functioned as fan service and promotional strategy simultaneously, Cole feeding his audience’s appetite while building anticipation for the retail debut. He released these tracks through his website, DreamVillain.net, bypassing traditional distribution channels entirely. The approach acknowledged that his core listeners had discovered him through free music and expected continued access even as he prepared to charge for his work.

Any Given Sunday, Vol. 2 (2011)

A week later came the second installment, three tracks that continued Cole’s pre-album generosity. “Bring Em’ In” originated during the single hunt phase in Atlanta, a song Cole loved despite its failure to secure that commercial slot. “Roll Call” found him venting, working through frustrations that wouldn’t fit the album’s more polished presentation. “Be (Freestyle)” completed the trio. Cole framed these releases as neither mixtapes nor EPs, just Sunday offerings for fans who had waited two years since Friday Night Lights for new material. The tracks revealed an artist caught between personas, balancing the hungry underdog energy that had built his audience against the more composed delivery his label likely preferred. Cole’s verses cycled through boasts and anxieties, sometimes within the same song. He could sound supremely confident in one bar and deeply uncertain in the next, the tension between ambition and insecurity surfacing repeatedly.

Any Given Sunday, Vol. 5 (2011)

Cole skipped volumes three and four entirely (dedicated to revealing updates to his debut album on Ustream), jumping to the fifth installment in August with typical disregard for the serial conventions he himself had established. The numbering quirk hinted at playfulness but also impatience, an artist unwilling to follow even his own arbitrary systems. This final Sunday release before Cole World contained just two tracks, “Heavy” and “Neverland,” the latter produced by Chase N. Cashe alongside Cole during sessions in Los Angeles. The abbreviated runtime signaled that Cole had said what he needed to say through free music. “Neverland” found him riding a beat he described as something to cruise to, a looser vibe than the more intense material populating the album sessions. Cole offered both tracks as gifts, songs that wouldn’t make the retail cut but deserved ears nonetheless. His verses on the project engaged his imminent debut directly, articulating anxieties about commercial pressure and artistic compromise with the self-aware candor that had become his signature mode. Cole spit about fears that success might dilute his music, that the machinery required to achieve mainstream recognition might grind down the rough edges his core audience loved. These were common enough concerns among ascending rappers, but Cole voiced them with unusual specificity.

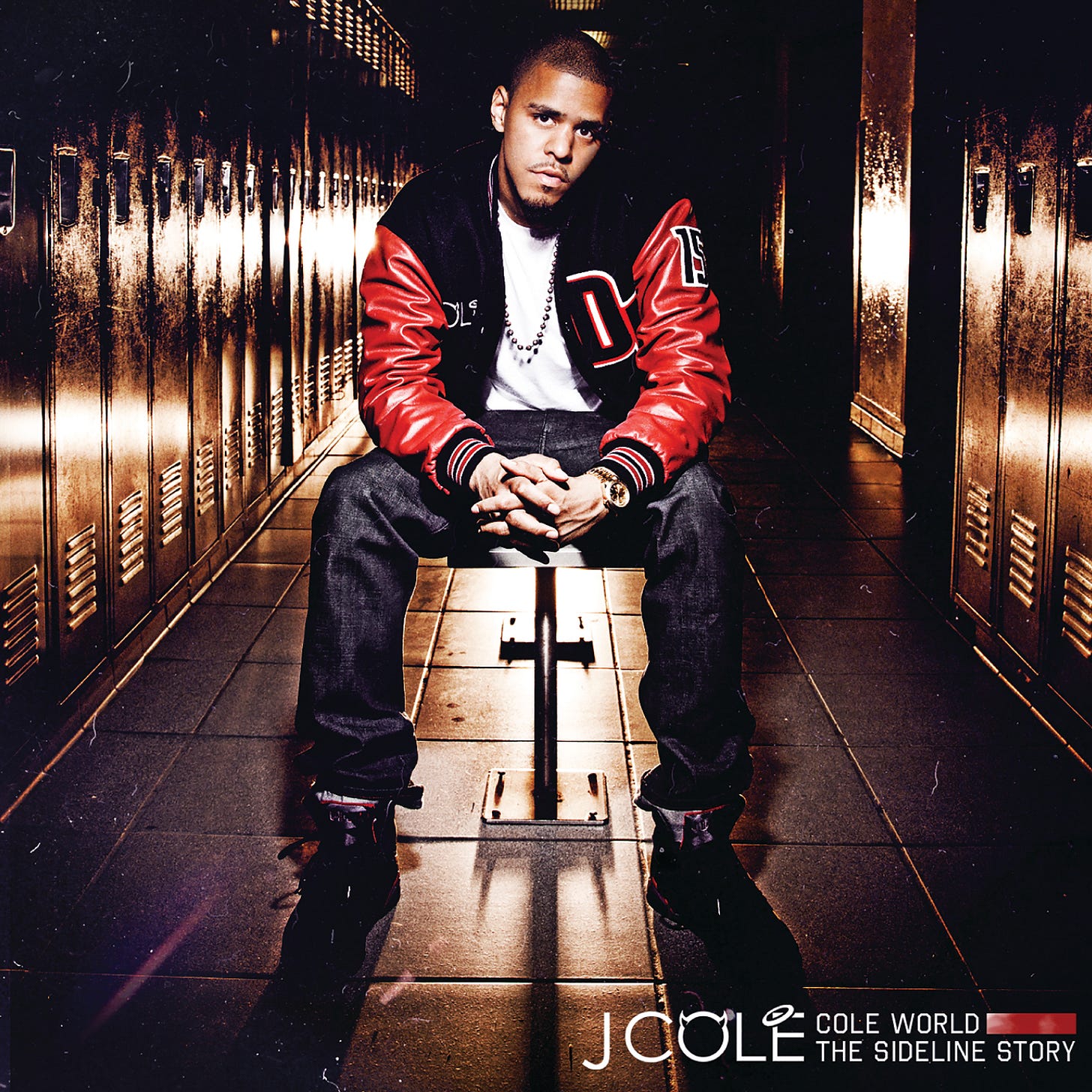

Cole World: The Sideline Story (2011)

The fall of 2011 found hip-hop’s release calendar impossibly crowded. Lil Wayne had returned. Drake was consolidating his throne. JAY-Z and Kanye West had just dropped their collaborative statement. Into this gauntlet stepped Roc Nation’s first signee with his retail debut, an album whose title referenced both his basketball ambitions and his observation post on rap’s margins, the position from which he had watched contemporaries achieve the success he craved. Cole World sought to transition him from spectator to participant, from sideline to court.

The project performed spectacularly by commercial metrics, debuting at the top of the Billboard 200 on the strength of “Work Out” and its radio-friendly bounce, though critical response divided sharply between those who heard mature craftsmanship and those who detected overcompensation and stylistic hedging. Cole had attempted to satisfy multiple audiences simultaneously, balancing club records against the introspective material his mixtape followers preferred. The strain showed in the album’s uneasy pacing.

Production split between Cole’s own work and contributions from established hitmakers like No I.D. and Brian Kidd, yielding a sonically varied but occasionally disjointed collection. Bright synthesizers powered the radio singles while murkier arrangements underlined the album’s moodier passages. The drums hit cleanly throughout, punchy and mixed forward in the contemporary blog-rap tradition that had incubated Cole’s initial audience.

The album’s commercial success guaranteed Cole’s future but also initiated debates about whether his major-label material could match his free releases. Those arguments would trail him for years, a persistent tension between commercial obligation and artistic reputation that he would address repeatedly in subsequent work.

Truly Yours (2013)

Two years separated Cole World from its follow-up, and the Truly Yours EP surfaced as reassurance that the delay had not diminished his capabilities. Cole had recorded at least four albums worth of material during the Born Sinner sessions, and these five tracks represented songs that wouldn’t make the final cut for reasons of sonic fit, thematic coherence, or simple space constraints. He released them through DreamVillain as a gift to fans who had waited patiently, describing the songs as raw and unpolished, just a lot of his soul. “Can I Holla at Ya” opened the project by sampling Lauryn Hill’s “To Zion,” Cole rapping three verses addressed to different figures from his past: an ex-girlfriend in the first, his stepfather in the second, and an old friend in the third. The confessional structure let him work through unresolved tensions without the commercial pressures that had shaped his debut. “Crunch Time” sampled Bootsy’s Rubber Band’s “Munchies for Your Love.” “Rise Above” flipped Dirty Projectors. “Tears for ODB” paid tribute to Ol’ Dirty Bastard while reflecting on Cole’s own struggles to make his dreams reality. “Stay,” recorded back in 2009, rode a No I.D. beat sampling L.A. Carnival’s “Seven Steps to Nowhere” that Cole had intended for Cole World but never purchased. Nas eventually used the same instrumental on his 2012 album Life Is Good, changes even as he wrestled with the artistic questions his debut had raised.

Truly Yours 2 (2013)

Born Sinner waited in the wings, its final production stages nearing completion. The sequel arrived at the end of April as another collection of songs that wouldn’t make the album cut, six tracks this time featuring guest appearances from Jeezy, 2 Chainz, and Bas. “Cole Summer” opened the project by sampling Ms. Lauryn Hill and D’Angelo’s “Nothing Even Matters” while interpolating Biggie’s “Juicy,” Cole rapping about the anxieties of fame over production he handled himself. In the song, he joked about hoping Lauryn wouldn’t sue him for the sample. “Kenny Lofton” paired Cole with Jeezy over a Canei Finch beat that sampled The Manhattans’ “Hurt,” the track named after the fleet-footed Cleveland Indians outfielder. “Chris Tucker” brought 2 Chainz aboard for something looser and more playful. “Head Bussa” and “3 Wishes” found Cole working through competitive instincts and wish-fulfillment fantasies. “Cousins” featuring Bas would later appear on Bas’s mixtape Quarter Water Raised Me Vol. II, an early example of Dreamville cross-pollination. The EP’s release coincided with announcements about Cole’s sophomore album and its audacious strategy of launching directly against Kanye West’s Yeezus, a scheduling collision that guaranteed press attention but risked unfavorable comparison. Cole seemed unbothered by the gamble, or at least performed confidence convincingly.

Born Sinner (2013)

Few sophomore albums have courted direct comparison so brazenly. By scheduling his second record for the same date as Yeezus, Cole forced a confrontation with the industry’s most acclaimed risk-taker that critics and fans dissected endlessly in the weeks surrounding both releases. Born Sinner offered itself as counterargument to Kanye’s abrasive, industrial experiments, a humid, soul-drenched record that privileged accessibility over innovation. Where Yeezus shrieked and lurched, Born Sinner grooved. The contrast could not have been starker.

The album processed Cole’s growing discomfort with fame’s moral compromises, returning repeatedly to questions about authenticity and ambition that had preoccupied him since The Come Up. He rapped about guilt and temptation in explicitly religious frameworks, borrowing confessional language from his Southern Baptist upbringing to structure his inquiries into desire and consequence. The single “Power Trip” featuring Miguel achieved massive radio success while maintaining thematic continuity with darker, more reflective material.

Production blended Cole’s own work with contributions from No I.D., Jake One, and a handful of other collaborators who shared his affinity for sample-based construction. Drums hit with dusty warmth, snares cracking against beds of chopped vocal loops and vintage keyboard tones. The tones recalled late-nineties Roc-A-Fella without merely imitating it, Cole filtering his influences through contemporary mixing techniques and drum programming conventions.

Despite its risky positioning, Born Sinner proves that Cole could compete commercially against hip-hop’s most prestigious names while maintaining his lyrical focus. The album would eventually achieve platinum certification, validating both his talent and his marketing bravado.

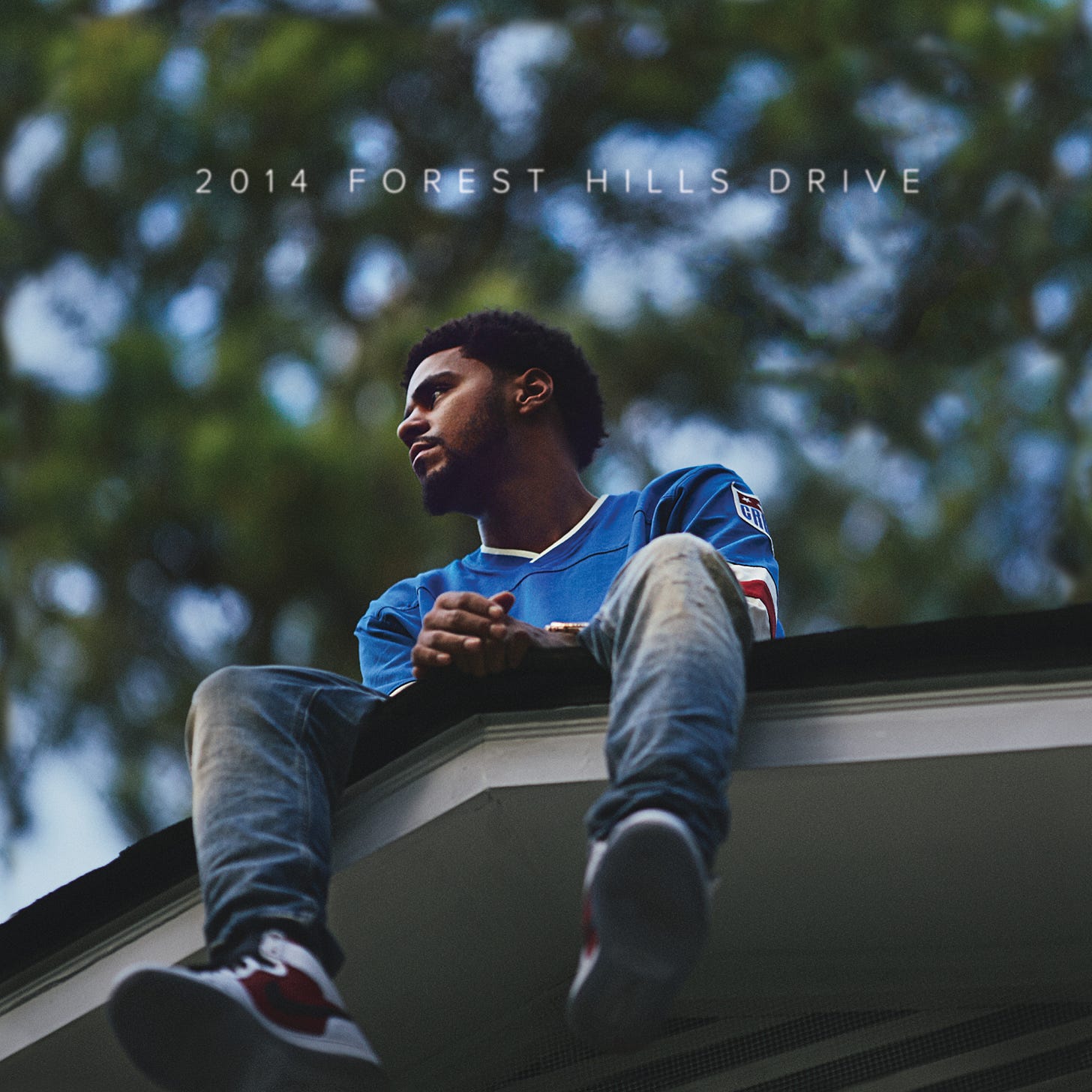

2014 Forest Hills Drive (2014)

No singles. No guest features. No typical promotional machinery. The album that would permanently establish Cole among hip-hop’s elite materialized as a gamble that trusted his audience to find the music without assistance. They did. Named for the Fayetteville address where he had spent his most formative years, the record debuted at the top of the charts and would eventually achieve triple platinum certification, numbers that demolished industry assumptions about unmarketable releases.

The project traced Cole’s childhood through a loose narrative framework, moving from his birth in Germany through his mother’s struggles with addiction and financial insecurity to his eventual rap ambitions and their complicated fulfillment. “Apparently” and “G.O.M.D.” engaged specific memories with documentary precision while extracting broader meaning from their particulars. Cole had discovered that autobiography could function as universal statement when rendered with sufficient care.

Production settled into warm, organic territory that avoided both the synthetic polish of Cole World and the occasionally overwrought sampling of Born Sinner. Drums breathed naturally. Pianos, samples, and strings appeared without excessive processing. The record sounded like musicians playing together in a room, an aesthetic choice that distinguished it from the increasingly computerized productions dominating hip-hop radio. Cole’s own beats mingled comfortably with contributions from Phonix Beats, Willie B, and Vinylz.

The album arrived during a period when hip-hop discourse had begun questioning whether streaming economics could support the album format at all. Cole’s success proved that coherent artistic visions could still galvanize audiences, that the album remained viable for artists capable of delivering complete experiences. 2014 Forest Hills Drive became reference point and rebuttal, evidence cited whenever the album’s death was prematurely declared.

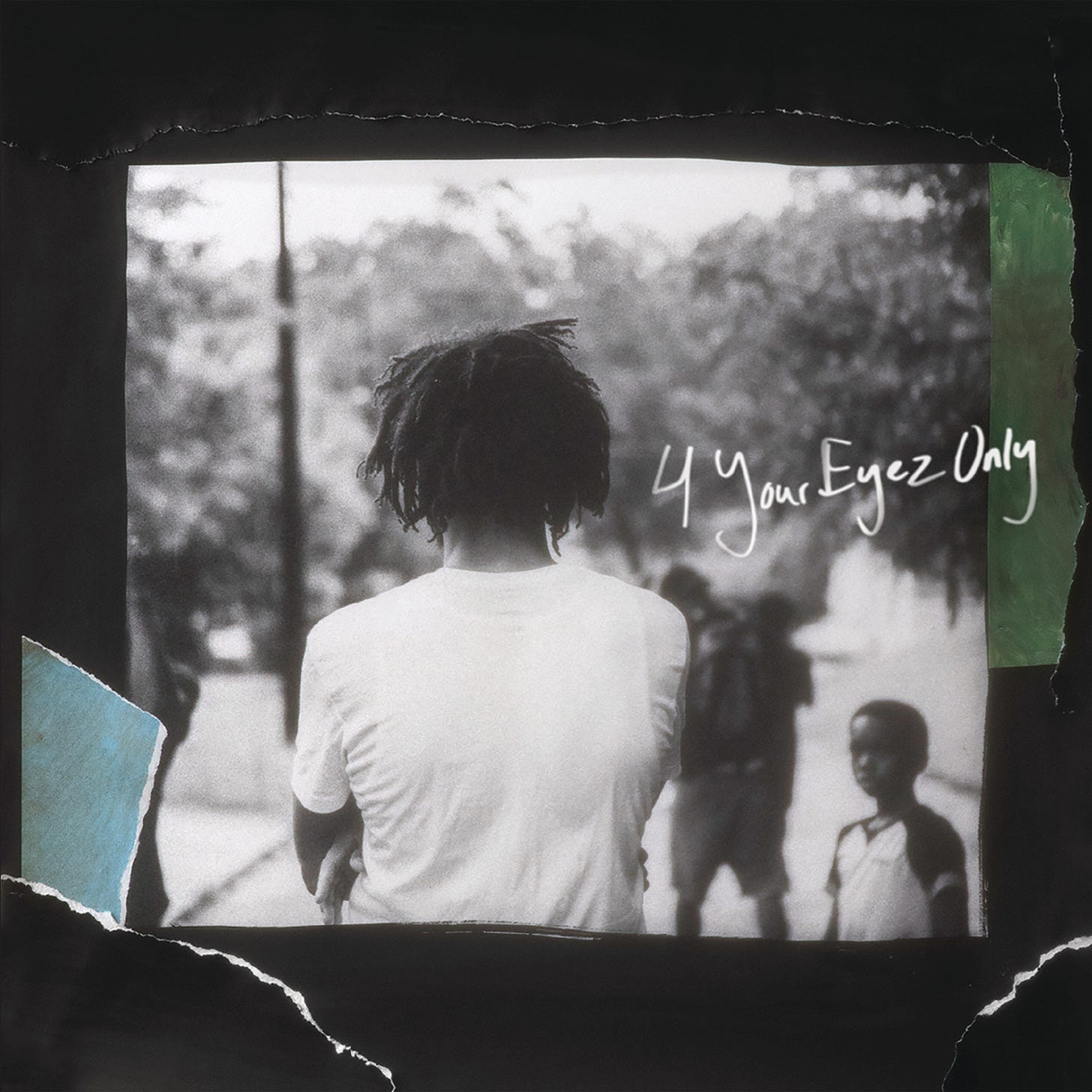

4 Your Eyez Only (2016)

Two years later, Cole returned with his most ambitious narrative undertaking, an album structured around the life and death of James McMillan Jr., a childhood friend murdered before he could see his daughter grow up. 4 Your Eyez Only devised itself as memorial and message, Cole inhabiting McMillan’s perspective across several tracks while processing his own grief and survivor’s guilt throughout others. The result blurred biography and invention in ways that demanded active listener engagement.

The album’s muted palette matched its funereal subject matter, drums hitting with subdued weight, tempos rarely exceeding mid-tempo, melodies dwelling in minor keys and circular progressions evoking contemplation rather than celebration. Cole had stripped away the competitive bravado that marked most rap releases, producing something closer to eulogy than ego-trip. The hard-hitters of “Immortal” and “Neighbors” addressed mortality and racial profiling without hedging or retreat, as well as the positive upbeat of “Change,” channeling 2Pac.

Production credits included familiar collaborators alongside new voices, though Cole’s own contributions continued to anchor the sound. His beats featured live instrumentation more prominently than previous releases, with bassist Christoph Andersson and guitarist Josh “Igloo” Sallee appearing across multiple tracks. The human performances lent warmth to material that might have felt sterile in purely programmed arrangements.

The album rewarded patience and repeated engagement, its pleasures emerging gradually rather than announcing themselves on first contact. Cole had learned to trust his audience’s attention spans, to construct records that unfolded over time rather than delivering all their impact immediately. This confidence would inform his subsequent work.

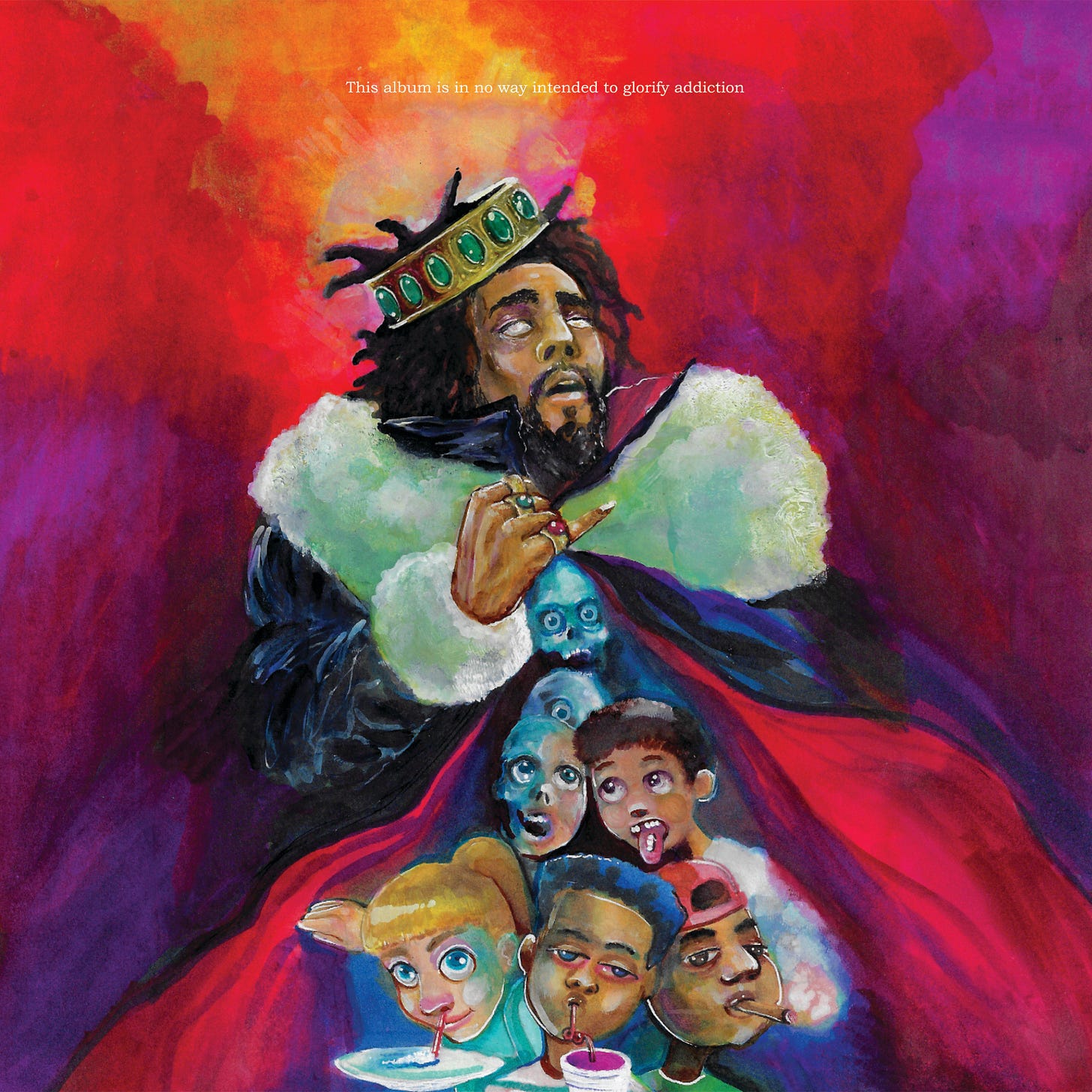

KOD (2018)

The opioid epidemic had reached its grim peak by the late twenty-tens, pharmaceutical companies pushing pills into every corner of American life while social media platforms engineered their own forms of compulsive dependency. Cole had watched friends and family members succumb to various forms of habitual behavior, and his fifth album channeled that observation into his most thematically unified project. The title acronymed into three separate meanings: Kids on Drugs, King Overdosed, and Kill Our Demons. KOD confronted addiction across its multiple manifestations, from substance abuse to screen fixation to the industry’s cultivation of need.

The album’s production marked a deliberate departure from the organic warmth of his previous two releases, folding in trap drums, pitched vocal effects, and the synthetic textures that dominated contemporary hip-hop. Cole seemed to be meeting commercial trends halfway while maintaining lyrical priorities that distinguished him from peers who employed similar sounds without substance. Tracks such as “ATM” and “Photograph” balanced critical perspectives with undeniable catchiness.

Guest appearances remained minimal, with only kiLL edward, Cole’s pitch-shifted alter ego, receiving featured billing. This fictional collaborator allowed Cole to voice perspectives and desires that might have felt uncomfortable attributed directly to himself, a ventriloquist’s technique that added dimension to the album’s psychological investigations. The device had precedents in hip-hop history but Cole deployed it with characteristic thoroughness.

KOD performed exceptionally upon release, its streaming numbers reflecting both Cole’s expanded audience and the format’s continued growth as primary consumption method. The album proved that commercially viable hip-hop could address serious social concerns without sacrificing accessibility or resorting to didacticism.

The Off-Season (2021)

Three years elapsed before Cole’s next proper album, a period during which he had signed a contract to play professional basketball in Africa, launched a festival, and collaborated selectively with other artists while largely withdrawing from the spotlight. The Off-Season landed as corrective to any perception that his competitive edge had dulled, a lean and aggressive collection that reminded listeners why they had monitored his ascent initially. Cole attacked the microphone with renewed intensity across productions designed to showcase technical ability above all else.

The album’s guest roster broke from his previous isolation, weaving in features from 21 Savage, Lil Baby, Morray, and others whose presence signaled Cole’s willingness to engage contemporary trends rather than merely observe them. These collaborations sparked debates about whether Cole was chasing relevance or simply expanding his palette, arguments that assumed commercial considerations and artistic ones must conflict.

Production drew from multiple contemporary hip-hop subgenres, blending trap rhythms, drill cadences, and the piano-driven melancholia that had pervaded pandemic-era releases. Cole’s own beats appeared alongside contributions from T-Minus, Timbaland, and Boi-1da, established hitmakers whose involvement implied label support for the project’s commercial ambitions. The results varied in character but maintained consistent energy throughout.

The Off-Season debuted at number one and generated Cole’s largest first-week streaming numbers, metrics that confirmed his mainstream standing while his artistic reputation continued evolving. He had proven again that commercial success and lyrical focus could coexist, that audiences still responded to rapping when executed at sufficient levels.

Might Delete Later (2024)

The beef had been simmering for years. Subliminal shots between Cole, Kendrick Lamar, and Drake had accumulated across features and loosies, the tension occasionally surfacing before retreating into plausible deniability. When the dam finally broke in spring 2024, Cole surprised everyone by dropping a project directly into the crossfire, a mixtape-style release that arrived without promotional buildup or advance warning despite appearing on streaming platforms that had largely eliminated the format’s economic rationale. The title suggested impermanence, a claim that subsequent weeks would test.

The release attracted attention primarily for its response to ongoing lyrical tensions with Kendrick Lamar and Drake, a three-way rivalry that had simmered for years before erupting during spring 2024’s concentrated exchange of subliminal and direct challenges. Cole’s verses on “7 Minute Drill” addressed Lamar specifically before Cole publicly retracted the song, removing it from streaming platforms and apologizing for engaging in conflict he had reconsidered. The reversal generated as much discussion as the original track.

With the help of T-Minus and DZL, the production carried forward The Off-Season’s contemporary orientation, layering trap drums and modern mixing techniques while Cole’s flows demonstrated the technical precision that had always characterized his strongest work. Guests included Cam’ron, Bas, and others from Cole’s Dreamville roster alongside newer voices, the collaborations suggesting both community maintenance and strategic positioning.

The project’s messy rollout and partial retraction complicated its reception, raising questions about artistic conviction and public relations calculation that Cole had largely avoided throughout his career. Whether Might Delete Later represented misstep or honest recalibration remained debated. Cole had always processed his career publicly, and this latest chapter provided ample material for ongoing examination.