The Handguide to Michael Jackson

As we’re approaching three months to the biopic, what better way to go down memory lane to the King of Pop, whose resume speaks for itself. From Jackson 5 to solo, we present 29 records.

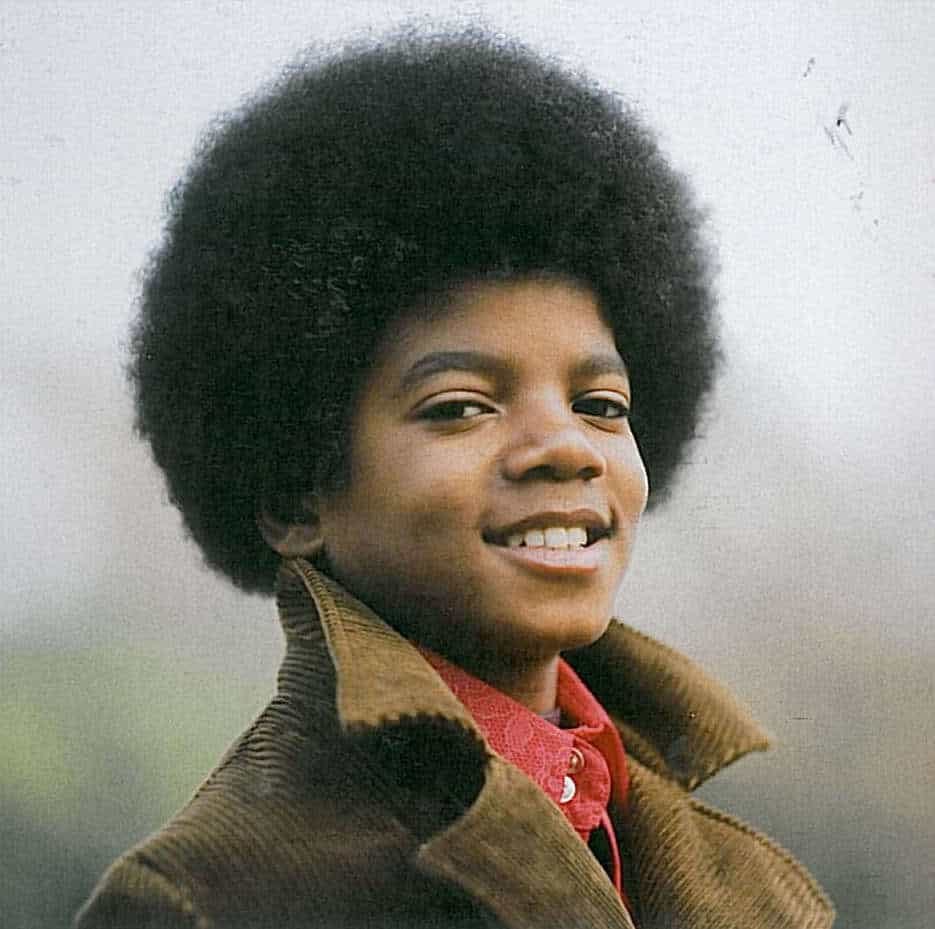

Indiana Soul Kid

Michael Jackson was born on August 29, 1958, in Gary, a steelmaking town in northwest Indiana. His father Joe was a factory worker and semi-pro guitarist, and his mother Katherine loved music. Michael had two sisters and four brothers.

The brothers used to sing and play on their own, but when they performed in front of their parents, Joe recognized their talent and began drilling them hard. Jackie, Tito, Jermaine, and Marlon were joined by five-year-old Michael (hereafter “MJ”), and the group fell into daily, Spartan rehearsals. The brothers were said to fear their father’s violent instruction, and the experience is often described as traumatic for each of them. Still, their ability as a music group steadily sharpened, and MJ’s singing and dancing in particular stood out as exceptional.

When MJ was around six, they began calling themselves the “Jackson Five” and entered local amateur contests. Through those competitions and nightclub appearances, they pushed into nearby Chicago and then all the way to Harlem’s Apollo Theater in New York. Their repertoire at the time was hard-driving soul music: James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Sam & Dave, and others. After scoring a local hit with their first single on a regional label, they started drawing attention from professionals and met Motown artists including Gladys Knight and Bobby Taylor. Taylor eventually arranged an audition in Detroit. After watching the filmed performance, Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. decided to sign the astonishing brothers. The Jackson family relocated to Los Angeles, where Motown had moved operations, and under Gordy’s direction a dedicated production team, The Corporation, was assembled for them. Suzanne de Passe served as their manager, and Diana Ross took on a mentoring role. The group’s name was standardized as “Jackson 5,” and their national debut was imminent.

Breakthrough at Motown

In November 1969, their debut single “I Want You Back” was released. After appearing on national television and displaying jaw-dropping skill and charm, the Jackson 5 (hereafter “J5”) quickly topped both the pop and R&B charts. “ABC,” “The Love You Save,” and “I’ll Be There” followed, each reaching No. 1 on both charts in succession, making them the most popular group in America.

In the early 1970s they were overwhelmed with recording, touring, and TV appearances, popular enough to inspire an animated series based on them. The crush of devoted fans made it difficult for them to go out, and MJ, then between 11 and 14, sacrificed much of his private life. Even so, J5 drew a broader age range than Motown expected. Production gradually shifted toward the seasoned Hal Davis, and MJ trained himself into a stronger “listen-and-feel” vocalist as well.

In the fall of 1971, MJ also debuted as a solo singer, scoring hits with “Got to Be There” and “Rockin’ Robin.” Around the same period, J5 appeared alongside other major stars at a large-scale charity concert in Chicago that was later turned into the film Save the Children.

From 1972 to 1973, as MJ entered puberty and his voice changed, J5’s run of hits cooled somewhat. They still carried out a world tour, and their first performances in Japan in 1973 left behind rare live recordings of MJ singing at full intensity. The demanding pace may have contributed to reports that MJ felt insecure about his voice after the change, believing he had not developed the adult voice he expected. Even so, J5 and MJ made a strong comeback in late 1973. “Get It Together” was a funky, powerful dance tune built around MJ’s slightly more mature voice. “Dancing Machine” leaned more boldly into the disco sound that was popular at the time; MJ’s “robot dance,” said to be inspired by street dancing, also caught on, helping turn the song into a major hit.

Around then, J5 made a guest appearance on Stevie Wonder’s “You Haven’t Done Nothin’.” For MJ, who was strongly motivated to write and produce, working with Stevie seems to have been energizing. By this point MJ was dissatisfied with Motown’s tight management system, feeling he could not make the music he wanted. Their father Joe, acting as manager, agreed and quietly searched for a new deal, ultimately landing a contract with Epic.

Gordy was furious and forbade them from using the “Jackson 5” name. The brothers re-debuted on Epic as “The Jacksons,” but Jermaine, who was already married to Gordy’s daughter, left the group and remained with Motown. Their youngest brother Randy joined in his place.

From The Jacksons to solo

The Jacksons’ post-Motown work was guided by the veteran team of Gamble and Huff, based in Philadelphia, one of the key centers of 1970s soul. MJ gained experience there as a sound-focused creator and also co-wrote songs with his brothers. At the same time, MJ was cast in the film The Wiz, and while in New York for filming he met Quincy Jones, who served as music supervisor. Quincy not only contributed to The Wiz soundtrack, but also helped on Jacksons projects including the hit album Destiny.

MJ then brought Quincy on as producer for his long-awaited solo album. The team also included key collaborators who would support him for years: keyboardist Greg Phillinganes, arranger Jerry Hey, and recording engineer Bruce Swedien.

Off the Wall (1979), MJ’s first solo album as a young adult, became a record-breaking hit. He wrote some of the material himself and co-produced parts of the project. For MJ, it marked a true starting line as a full-fledged artist, transforming the voice he had felt conflicted about into a major asset. Still, he did not win the multiple Grammy awards he had aimed for, and that frustration fed into his next work.

The achievements of Thriller and Bad

MJ’s second solo album with Quincy Jones, Thriller (1982), was created under intense pressure, with work running in parallel to a spoken-word album tied to E.T. that included new music. The release came after a difficult process, but the outcome is widely known: an unprecedented blockbuster, with total worldwide sales recorded at over 100 million copies.

The strength of the songs is obvious, but those staggering sales also can’t be separated from MJ’s role in pushing music video forward. Starting with “Billie Jean,” which helped force MTV to open its doors more fully to Black music, followed by “Beat It,” and then capped by “Thriller,” the run of landmark videos changed how people consumed music. The images carried a mass appeal that crossed genre and racial boundaries with ease.

MJ also secured defining status through dance. During the televised “Motown 25” anniversary show in 1983, he performed “Billie Jean” and unveiled the moonwalk, a body movement that became one of his signatures (often said to draw inspiration from earlier performers like Cab Calloway and Charlie Chaplin).

Thriller won eight Grammy awards, and MJ went on tour with The Jacksons. During that period, while filming a commercial, a pyrotechnic mishap caused MJ severe burns. This incident is often cited as a factor that led to his later reliance on painkillers. After recovering and finishing the tour, MJ formally left The Jacksons and focused on solo work.

A major project from this era was “We Are the World,” the Africa famine relief charity single co-written with Lionel Richie, which further elevated MJ’s public stature. He also appeared in the Disneyland-exclusive film Captain EO. By the time he released Bad, he carried an overwhelming presence, like a solitary genius. Around then, his younger sister Janet achieved major success with Control. No longer just his “little sister,” she went on to release multiple standout albums, including Rhythm Nation 1814, becoming at times a rival and at times an adviser, and an important support in MJ’s life.

On Bad (1987), MJ teamed with Quincy a third time, but this time MJ wrote most of the material himself. The music pushed toward more distinctive sounds and song shapes than before and produced even more major hits than Thriller. He also launched his first solo world tour, including two visits to Japan for large-scale performances. Around the same time, the film Moonwalker was released. After Bad, MJ ended his collaboration with Quincy.

Mounting troubles and a sudden death

MJ began his next project writing and producing on his own, but partway through he shifted toward collaboration with younger creators, likely seeking the spark that can come from chemistry with others. He chose Teddy Riley, a leading figure in contemporary dance music. The resulting album, Dangerous (1991), built roughly half its tracks through that partnership. It was a major success and is often seen as a work where MJ gained new strengths.

While touring worldwide, MJ delivered a legendary Super Bowl halftime show performance in 1993. After that, he faced a serious crisis: allegations of child abuse connected to his home, commonly known as Neverland. Today the allegation is widely argued to have been an extortion attempt targeting his wealth, but at the time it became a massive scandal and inflicted deep damage on him.

The 1995 album HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I was released as a two-disc set paired with a greatest-hits collection. The disc of new songs contained especially raw lyrics that seemed to expose fresh wounds from the scandal, and while it included many strong tracks, it was heavier than his earlier work.

In 1997 he abruptly released the remix collection Blood on the Dance Floor, which also included several new songs. He then released Invincible in October 2001, after a long development period. The month before, in September, he held a 30th-anniversary solo concert in New York. After the September 11 attacks that followed, he also moved to support charity efforts for victims.

Not long after, another child-abuse allegation arose and became a criminal trial. Until he was acquitted in 2005, he was forced into a halt in his activities, and it is said his health suffered as well.

After several years away, in 2009 MJ announced a major run of concerts in London, his first on that scale in about 13 years since the HIStory tour. All 50 shows sold out, and rehearsals in Los Angeles were reaching their final stage. Then, on June 25, news of his death suddenly spread around the world.

He was 50 years old. What he left behind, and the emptiness of his absence, were both immense.

Diana Ross Presents The Jackson 5 (1969)

The Jackson 5’s signing to Motown began with an introduction from Bobby Taylor of Bobby Taylor & the Vancouvers. But to maximize publicity, Motown released their debut album under Diana Ross’s name. It was essentially a rush job put together after “I Want You Back” hit No. 1 on both the pop and R&B charts the month before. “I Want You Back” was the only single (and it had originally been written for Gladys Knight & the Pips), while most of the rest were covers: “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” from a Disney film, and the Miracles’ “Who’s Lovin’ You,” which they’d already been singing on talent shows. “Standing in the Shadows of Love,” “Chained,” “(I Know) I’m Losing You,” and “Nobody” came from within the label.

Outside of “I Want You Back,” little of it feels fully worked out, and about half the album being produced by Bobby Taylor may have been an apology or a favor. Even so, it became a blockbuster. The real curveballs are the Philly-soul lean of “Can You Remember” and the Sly cover “Stand!”—both closer to the group’s taste than Motown’s house idea of them. The Philly direction stays in play on later albums, and “Stand!” even opens the same way Sly’s “Sing a Simple Song” does. The lyric’s “midget” line also recalls the story that, before the debut, an adult performer who assumed Michael was grown called him that backstage—maybe Jermaine too. With Jermaine getting a lead and more older-leaning material in the mix, it also reaches beyond a kids-only audience. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

A fast-built debut that leans on covers, but the group’s blend is already tight and the hook-writing on “I Want You Back” is elite. The more left-field picks (“Who’s Lovin’ You,” “Stand!”) hint at how quickly they could stretch beyond candy-pop.

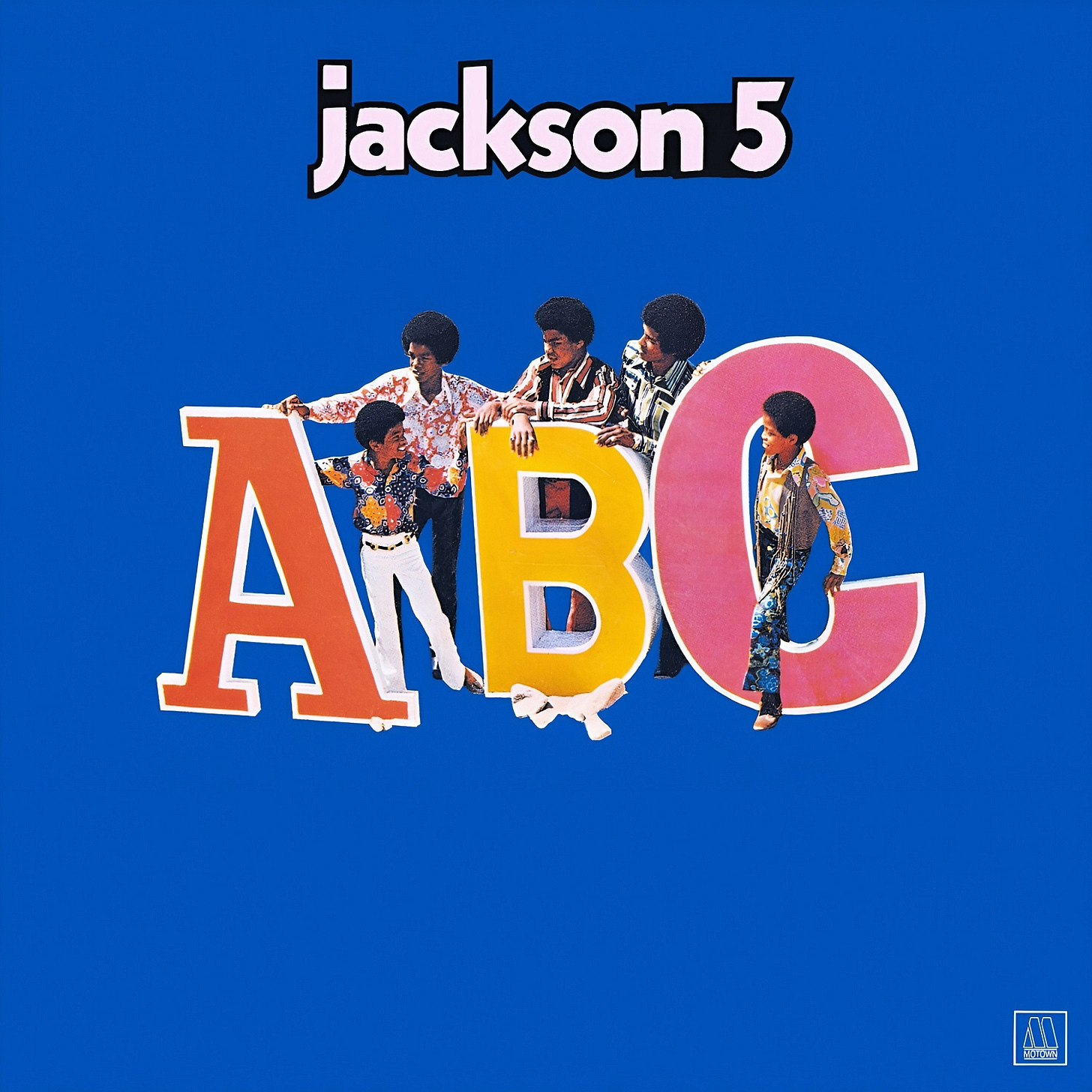

ABC (1970)

While “ABC” (their second single) was knocking the Beatles’ “Let It Be” off the top of the pop chart, Motown turned around a second album just five months after the first. Two months later, “The Love You Save” made it three straight No. 1 singles from their debut. The Corporation handled “The Love You Save,” “ABC,” and “One More Chance,” while Hal Davis focused on a more soulful lane aimed at slightly older fans, including “2-4-6-8,” “(Come ‘Round Here) I’m the One You Need,” “Don’t Know Why I Love You,” “Never Had a Dream Come True,” “La-La (Means I Love You),” and “I’ll Bet You.” Covers were still plentiful: Motown material like “(Come ’Round Here) I’m the One You Need,” Stevie Wonder’s “Don’t Know Why I Love You” and “Never Had a Dream Come True,” Philly’s “La-La (Means I Love You),” and Funkadelic’s “I’ll Bet You.” You can’t really expect the original sweetness of “La-La (Means I Love You)” to carry over, but most of it is handled well, and Michael’s capacity to absorb styles is hard to miss. His full-throttle singing on “Don’t Know Why I Love You” is especially striking. And since Funkadelic also cut “I’ll Bet You” with help from the Funk Brothers, the Jackson 5 version stays unusually faithful in both arrangement and vocal approach. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★½ (4.5/5)

The bright singles run on pure momentum, and Michael’s command keeps the album from collapsing into hits plus filler. Even with a pile of covers, the performances stay sharp, especially when the material asks for real power instead of pep.

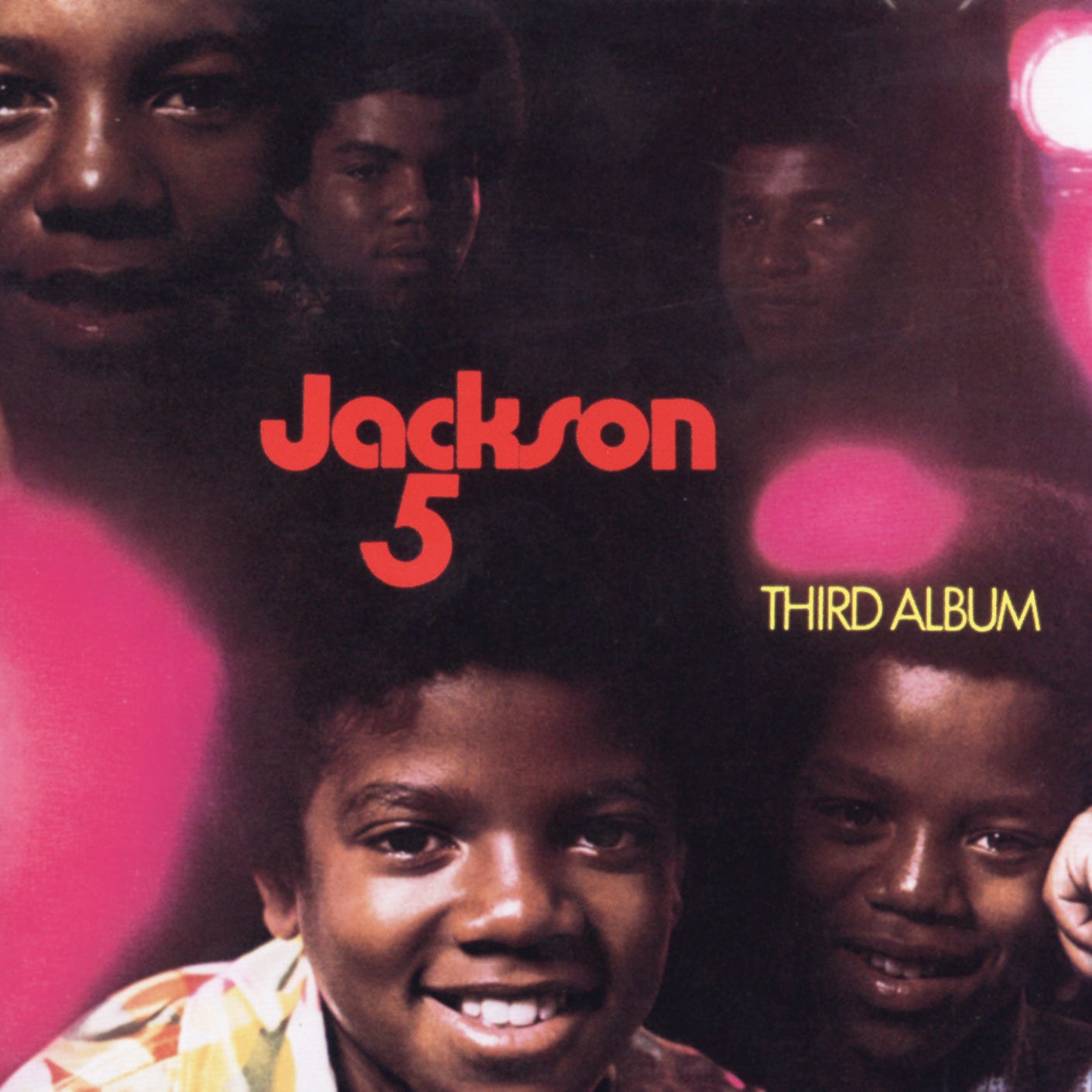

Third Album (1970)

A third album arrived another five months later. Production settled into a two-pillar system—The Corporation and Hal Davis—and each side handled both uptempo and slow material. With Hal Davis’s ballad “I’ll Be There” as the lead single, they became the first act to take their first four singles to No. 1 on both the pop and R&B charts. Covers had become a pattern by now: Philly selections like the Delfonics’ “Ready or Not Here I Come (Can’t Hide from Love),” internal Motown choices like “Oh How Happy” and the Miracles’ “The Love I Saw in You Was Just a Mirage,” plus Simon & Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” while originals started to increase. You can hear them experimenting too: the heavy use of strings on “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” the more psychedelic stretch of “Can I See You in the Morning,” and the horn-forward push on “Goin’ Back to Indiana.” James Jamerson’s constantly moving bass line on “I’ll Be There” is another detail that grabs you. Their next single, “Mama’s Pearl,” peaked at No. 2 on both charts. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

“I’ll Be There” is the emotional center, and the group sounds more confident moving between gospel-leaning balladry and harder funk takes. It’s also an early sign that they could handle bigger arrangements without losing their snap as a unit.

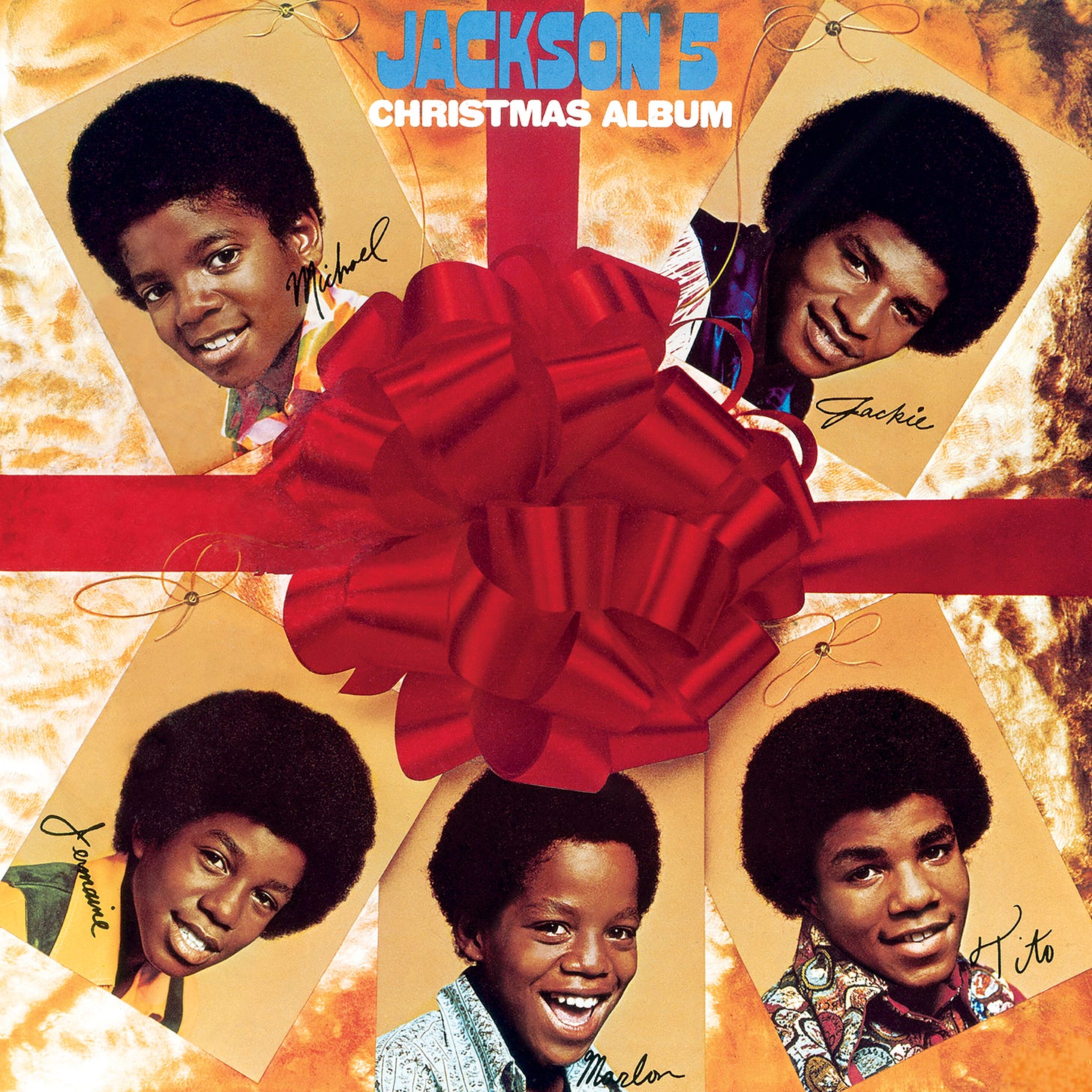

Christmas Album (1970)

Even as a Christmas album, this was their third release of 1970. With a few exceptions, it’s familiar holiday repertoire, still produced by The Corporation and Hal Davis. Apart from the more solemn “The Little Drummer Boy,” most of it is built the same way as their “regular” albums: upbeat arrangements in a Jackson 5 style, slower tracks led by Jermaine, and group shout-alongs that borrow from the Sly & the Family Stone playbook. The downside is that Michael misses pitch in small but noticeable ways, which suggests a short preparation window. The originals, as far as I know, are “Christmas Won’t Be the Same This Year” and “Give Love on Christmas Day.” “Christmas Won’t Be the Same This Year” opens with a cute little skit—“Jermaine is crying!”—and “Give Love on Christmas Day” is a Philly-leaning slow jam with Michael up front. The bass on Stevie Wonder’s “Someday at Christmas” also makes you wonder if it’s Jamerson again. — P

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Holiday standards get converted into Jackson 5 format, quick tempos, clean harmonies, and kid-show charisma that doesn’t feel cynical. The originals give it extra personality, even when Michael’s pitch wobbles now and then.

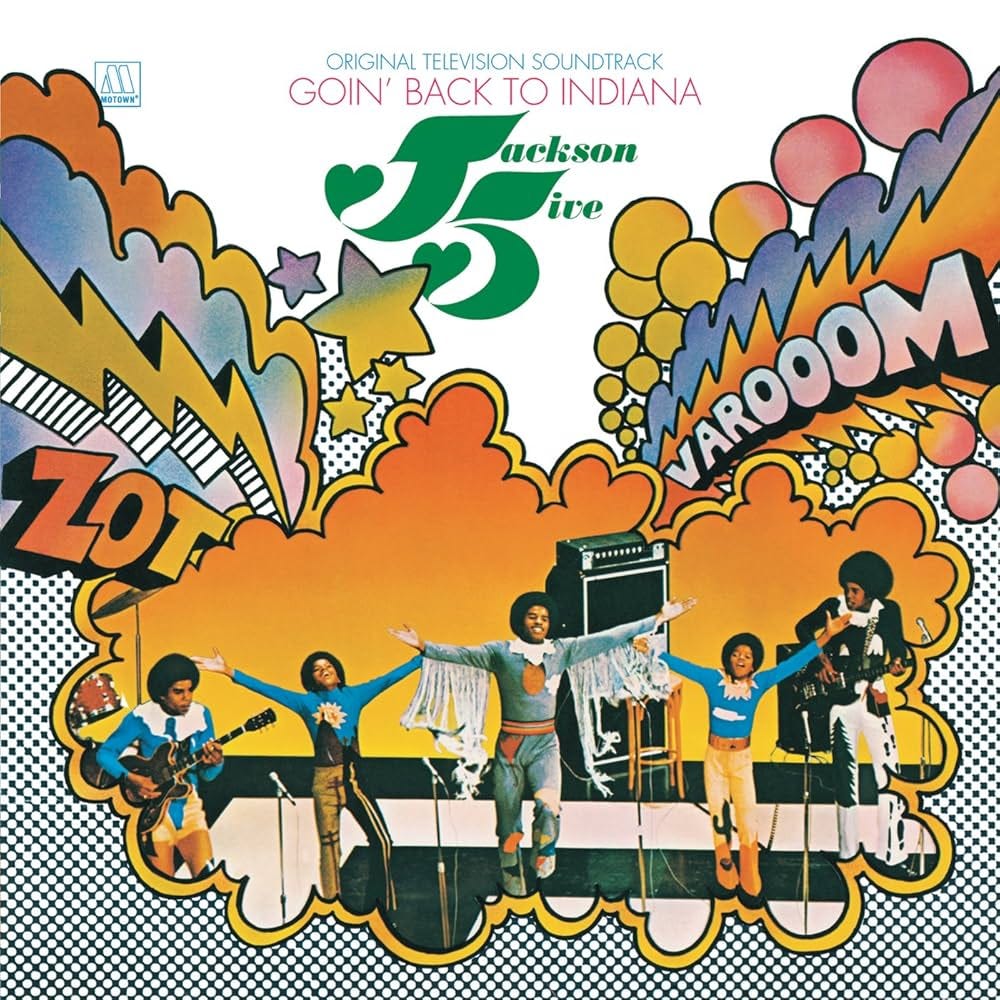

Goin’ Back to Indiana (1971)

This album compiles recordings from two sources: tracks from the May 1971 homecoming concert in Gary, Indiana (“Stand!” through “Goin’ Back to Indiana”), and tracks from the TV special that led into it (“I Want You Back,” “Maybe Tomorrow,” and “The Day Basketball Was Saved”). It was released in late September, about ten days after the special aired. Since the show mixed skits with live performances, the opening tracks include dialogue from guests like Bill Cosby. The song choices for the TV portion are smart: “I Want You Back,” the then-current single “Maybe Tomorrow,” and the jazz-rap novelty of “The Day Basketball Was Saved,” performed during a basketball scene. Once the live portion starts, the audience frenzy is obvious, but what’s more startling is how disciplined the group is onstage. Michael is 12, Jermaine is 16. It’s hard not to think about how much of that precision traces back to Joe Jackson’s notorious training methods. They also performed songs not included on the album (such as “Who’s Lovin’ You” and “Mama’s Pearl”), and even tried out newer material like “Never Can Say Goodbye.” — P

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

The live section proves how disciplined they were onstage, tight cues, locked vocals, and a band feel that doesn’t smear under scream-level crowd noise. Even with skits and TV audio baked in, the performance side carries real weight.

Maybe Tomorrow (1971)

Released as their fourth studio album, this one arrived while “Never Can Say Goodbye” (which peaked at No. 2 on the pop chart but returned them to No. 1 on the R&B chart) was still in motion. The producer setup stayed the same: The Corporation and Hal Davis. Clifton Davis’s “Never Can Say Goodbye” was produced by Davis, and it’s a classic—later a major hit for Gloria Gaynor as well—and its polished, smooth groove has been reappraised by “free soul” listeners, too. You can hear Michael starting to restrain his natural exuberance here, and that control opens up his range as a singer. Hal Davis’s “Petals” is pop enough that it makes sense Jermaine takes more of that load. The Corporation had basically perfected a “Jackson 5 style,” but the downside is that more and more of their work starts to feel like a re-run of earlier hits. They had tried psychedelia on the prior album, and now Hal Davis extends that direction on “(We’ve Got) Blue Skies,” which has an eerie, mystical beauty. One of its writers, Native American songwriter Tom Bee, landed a Motown songwriting deal off the back of it. The next single was The Corporation’s ballad “Maybe Tomorrow,” which you could almost call their answer to Hal Davis’s earlier “I’ll Be There.” With big summer and winter tours that year (40–50 dates each), their release pace would soon shift. — P

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

A pivot record where Michael starts dialing back the “kid lead” intensity and sings with more control and nuance. Not everything hits, but the title track and the stranger psychedelic corners show the group widening their range.

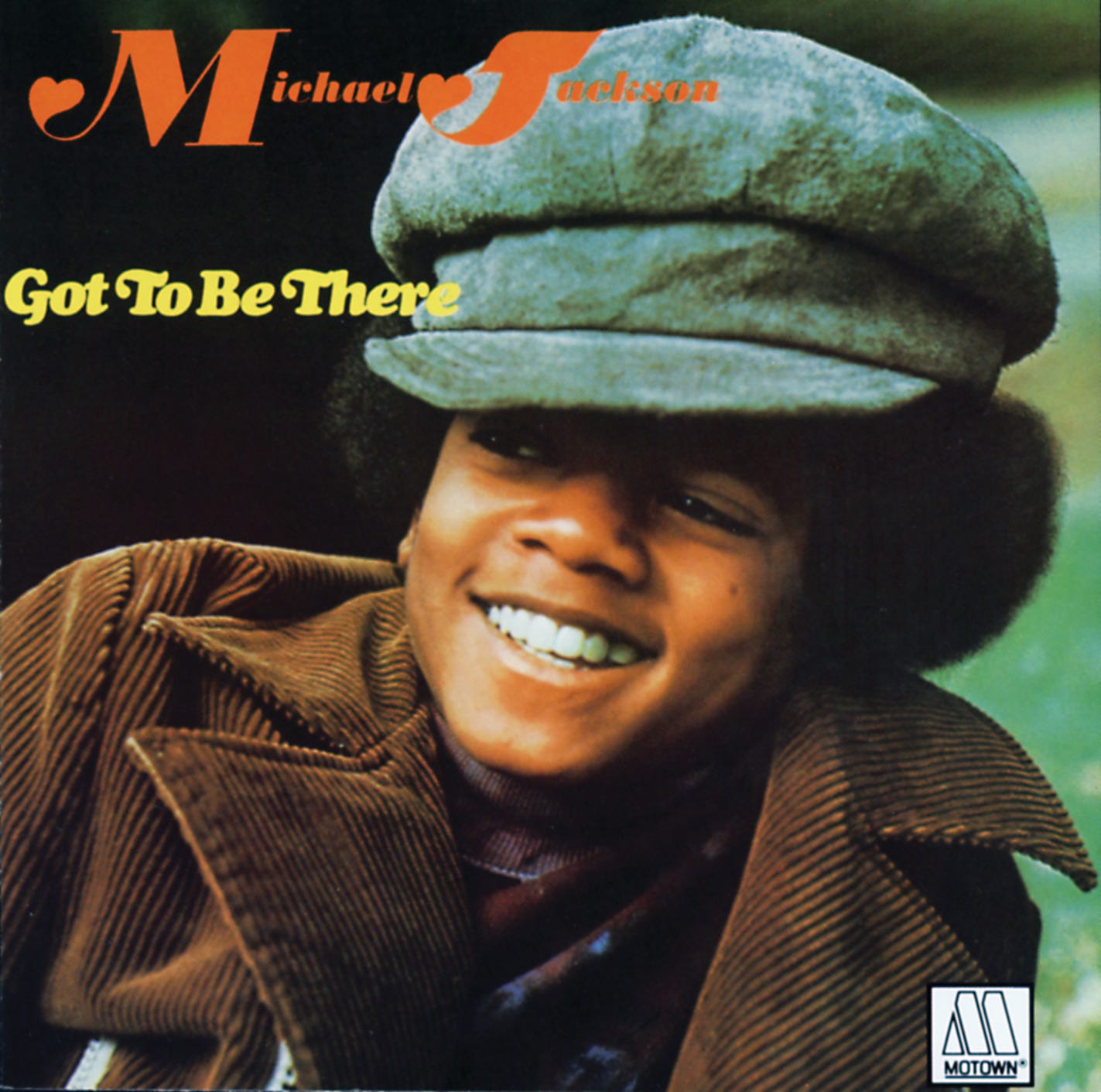

Got to Be There (1972)

With a Jackson 5 best-of already out and “Sugar Daddy” hitting, Motown finally issued Michael’s first solo album. New producers (including Willie Hutch) join the mix. The cover choices are familiar by now: Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine,” a fun rock-and-roll standard “Rockin’ Robin,” and the Supremes’ “Love Is Here and Now You’re Gone,” with older and newer material blended together. Some songs (“Ain’t No Sunshine,” “Girl Don’t Take Your Love from Me,” “Maria (You Were the Only One)”) have the kind of shape Jermaine might have taken on a group album, and the whole record can feel like a Jackson 5 LP where Michael simply takes every lead. That may have been Motown’s ceiling for the project. “You’ve Got a Friend” seems less about Carole King’s version than the Danny Hathaway/Roberta Flack hit that summer, which suggests Motown didn’t want to lose older listeners either. “Maria (You Were the Only One)” also keeps Hal Davis’s quiet psychedelic interest alive; the stacked guitars even brush against Funkadelic. The second single, “Rockin’ Robin,” ended up bigger than “Got to Be There,” and the third single was the Philly-leaning, more adult “I Wanna Be Where You Are.” — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

A solo album that still feels like a group record in structure, but Michael’s personality is strong enough to carry full-lead duty across wildly different material.

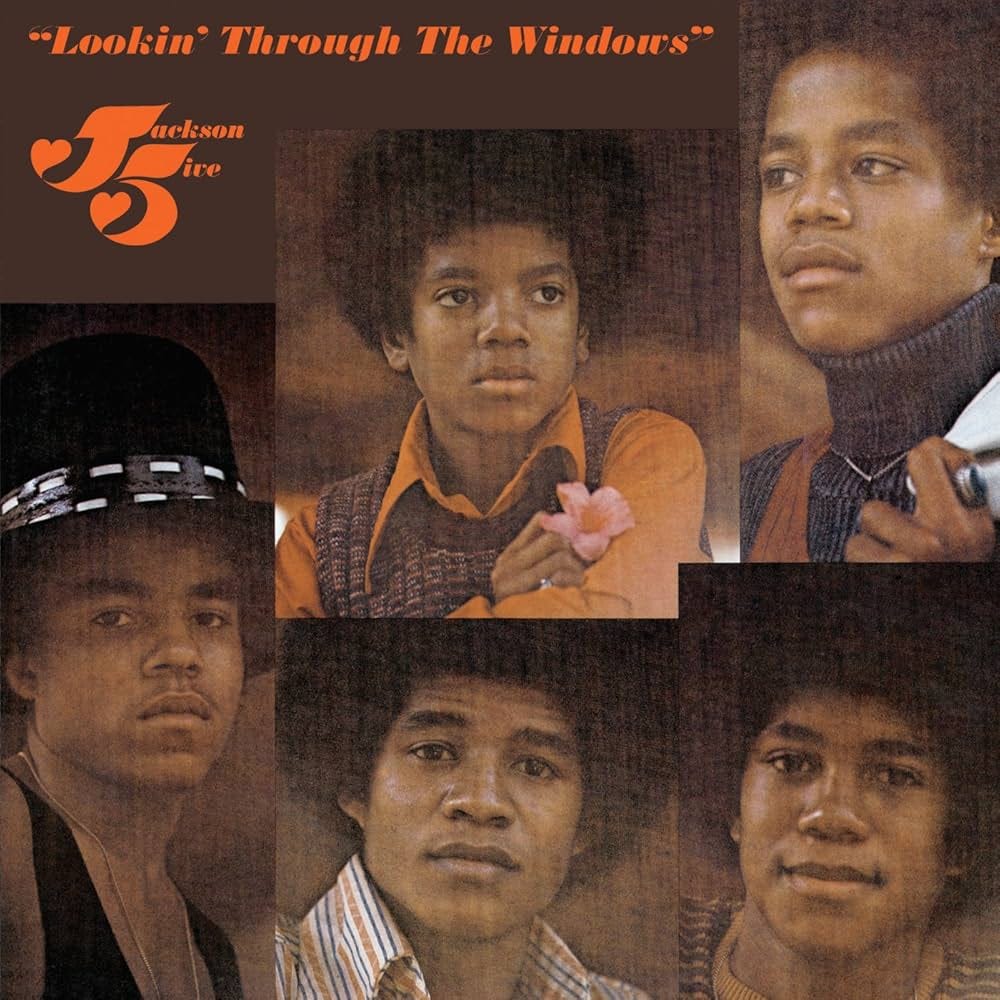

Lookin’ Through the Windows (1972)

As releases began to intertwine group and solo work, Motown’s single strategy got complicated. They led with the familiar, upbeat “Little Bitty Pretty One,” then followed it with Michael’s solo single “I Wanna Be Where You Are,” and then another smooth, more adult-leaning single before dropping the next Jackson 5 album. The two-producer system remained, with new faces added gradually. The more elaborate arrangements—some leftover Motown fingerprints mixed with a West Coast fusion polish—suggest a slow, careful attempt at shedding their earlier skin. Michael tries out falsetto and breathier deliveries on roughly half the tracks, but it often feels like he’s being dressed up in someone else’s concept of “grown,” and he still sounds best when he’s allowed to sing freely. Around this time, he reportedly went straight to Berry Gordy because he couldn’t accept the way producers were instructing him to sing, and Gordy made room for him to do it his way. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

You can hear Motown polishing them toward a sleeker, older audience, sometimes with mixed results when the vocal direction feels too imposed. When Michael’s allowed to sing straight and open, the songs land harder and the group blend sounds less boxed in.

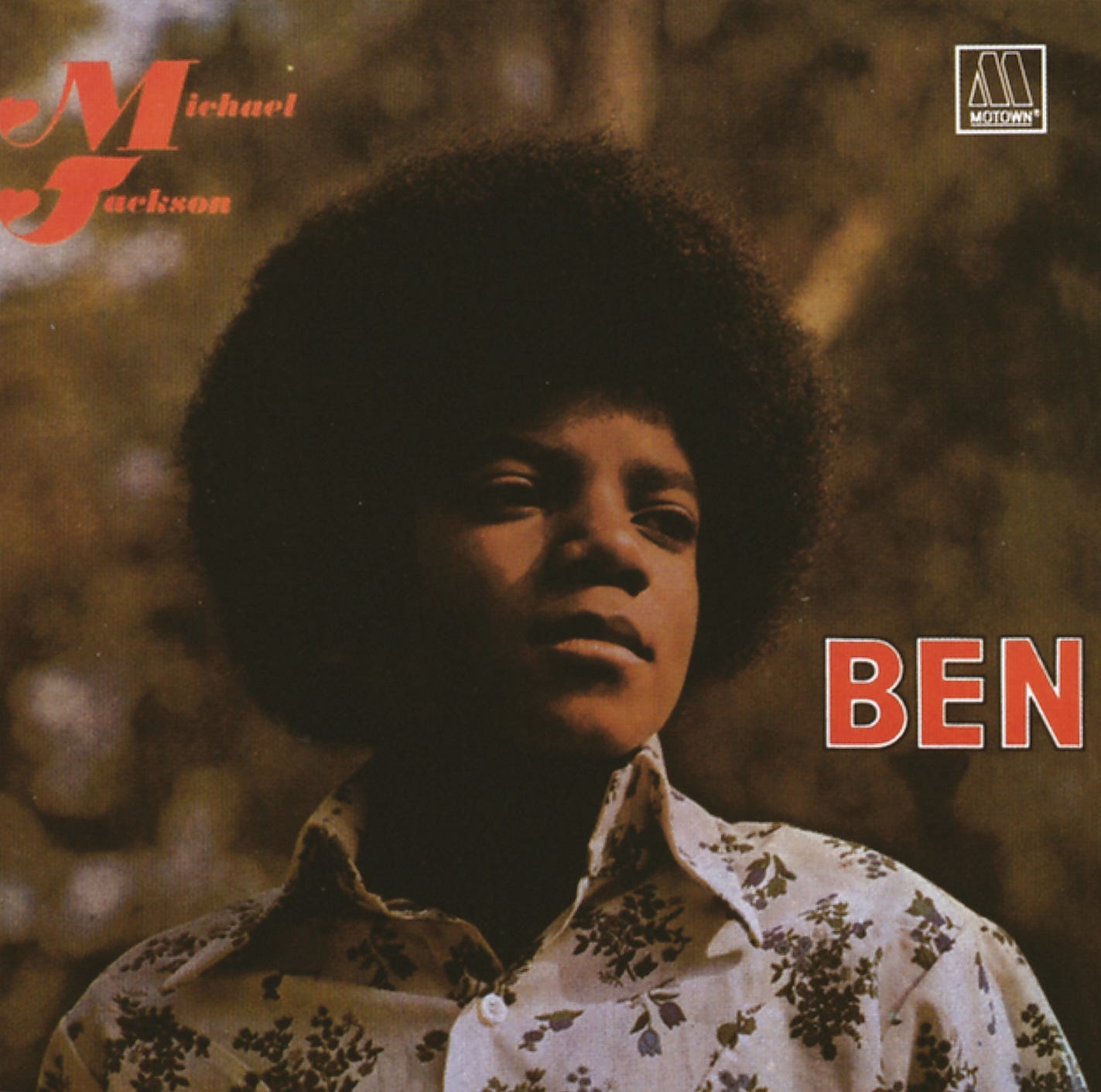

Ben (1972)

At a moment when the group’s uncertainty was starting to show, the film theme “Ben” becoming a pop No. 1 again must have been a relief. The story is about a sick boy who befriends a rat that the town dislikes, and Michael’s singing on “Ben” stands out partly because he genuinely loved the film; you can hear the emotional alignment without him forcing it. This second solo album also includes tracks with brothers on chorus, and songs like “Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day” that feel like they come from slightly earlier sessions, which suggests the main mission was simply: build a solo album around “Ben,” no matter what. Still, it’s a surprisingly full record. If his direct appeal to Berry Gordy bought him more room, you can hear it. There’s still a bit of that “assigned” whisper-singing on “What Goes Around Comes Around,” but in general he’s allowed to sing openly. The more adult, smooth “Greatest Show on Earth,” and the Stylistics cover “People Make the World Go Round,” both work because he doesn’t clutter them up; he just sings with real control and contrast. The same goes for the Temptations staple “My Girl” and the funkier Stevie cover “Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day.” Meanwhile, The Corporation’s contributions start to lose their shine—and that’s a change worth welcoming. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

The title song is a genuine vocal performance, not just a “child star sings a movie theme,” and it sets the bar for the album. Around it, the tracklist can feel assembled, but Michael’s ease on the best cuts keeps it from sounding like leftovers.

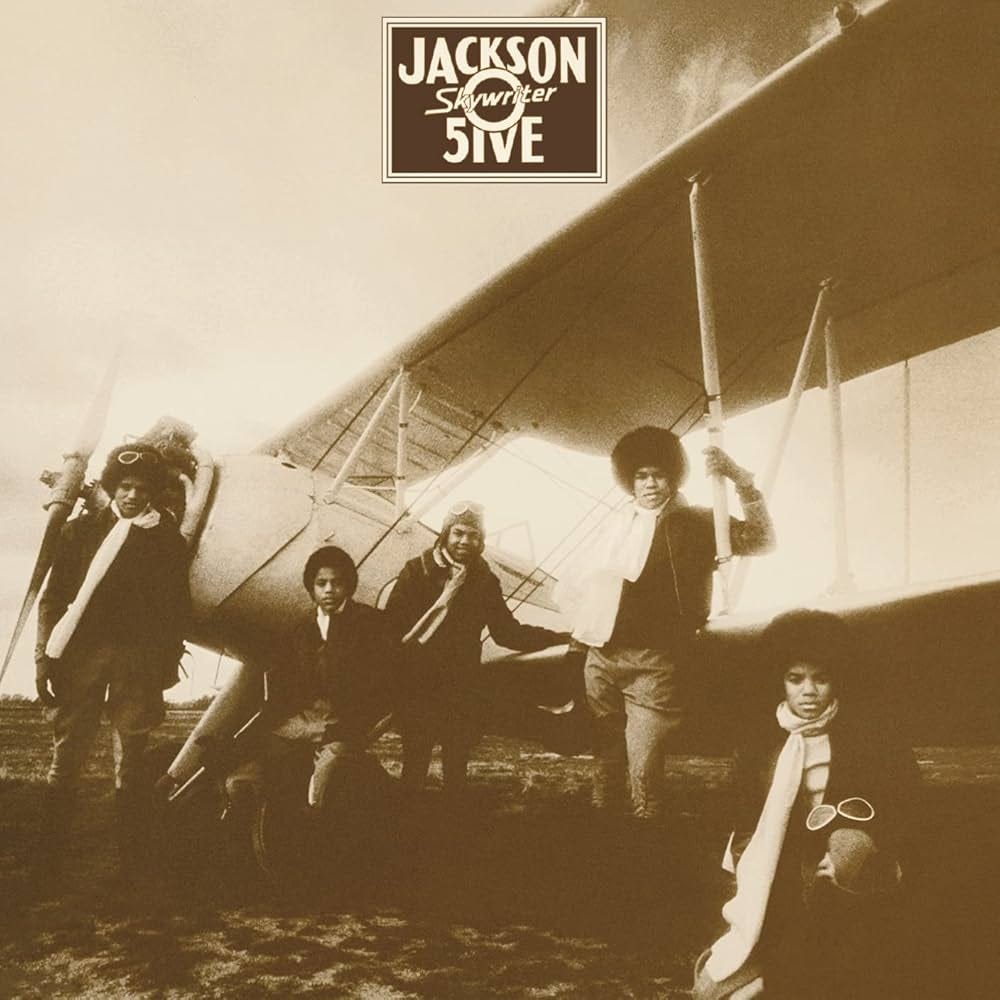

Skywriter (1973)

With Jerry Marcellino and others now firmly part of the inner circle, and The Corporation reduced to a single team-credited contribution (with members otherwise appearing under individual names), the production structure clearly changes. The lead single “Hallelujah Day” was effectively the last release in their early “bright and energetic” lane, and since it didn’t do much on the charts, the group was clearly at a turning point. Motown’s internal cover-pipeline also fades; instead you get the “Pippin” song “Corner of the Sky.” In the Hal Davis/Gene Page pairing, Michael’s vocal on “I Can’t Quit Your Love” sounds tougher than it ever had—shouts included—and it’s genuinely sharp. Still, the album as a whole is uneven, and the novelty-blues feel of “The Boogie Man” lands as more puzzling than persuasive. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

Michael’s voice toughens up, and the best cuts lean into that grit instead of cute choreography-pop. The album is uneven, but its high points have a bite and vocal muscle the earlier records only hinted at.

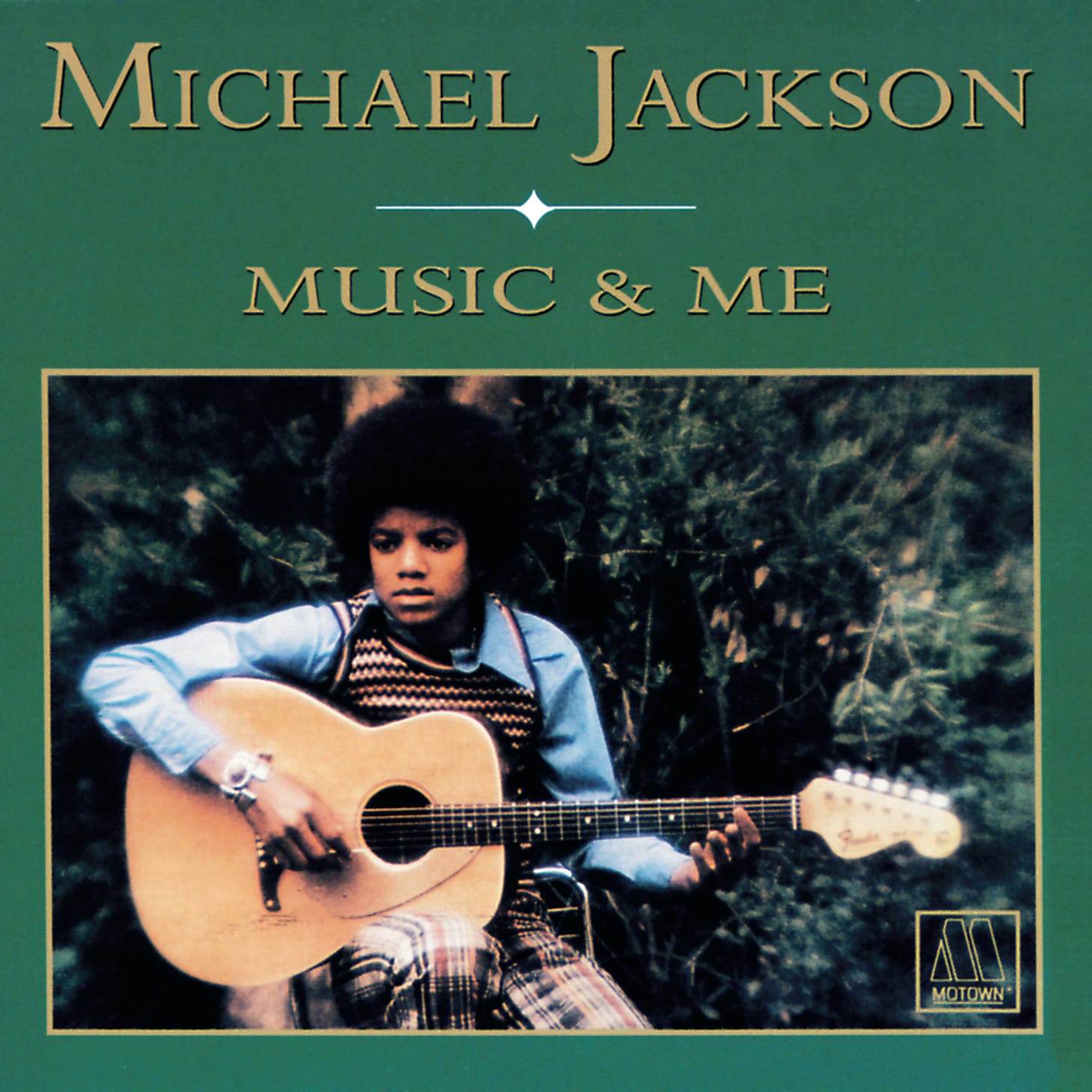

Music & Me (1973)

Released right on the heels of the group’s Skywriter, this third solo album was obviously recorded in parallel, and it still includes plenty of material that could have been issued under the group name without anyone blinking. The personnel are similar, but Hal Davis and Gene Page function as the structural backbone here, covering about half the record. As with a lot of this period, the recording dates span enough time that Michael’s voice appears in two forms: the thicker tone that hints at the change you hear on Skywriter, and the younger voice from earlier sessions. The thicker voice is especially strong on “Morning Glow,” a song also found on Pippin. Other covers range widely: Diana Ross’s film ballad “Happy,” the Nat King Cole standard “Too Young,” and Jackie Wilson’s “Doggin’ Around.” The Philly-leaning “All the Things You Are” is a good song on paper, but he sounds slightly strained and can’t quite sing it all the way through. — P

Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3/5)

The mixed-era vocals make it uneven, yet the strongest performances show a singer learning how to phrase like an adult without forcing it. When the material sits in the right key and tempo, he sounds focused and unusually controlled for his age.

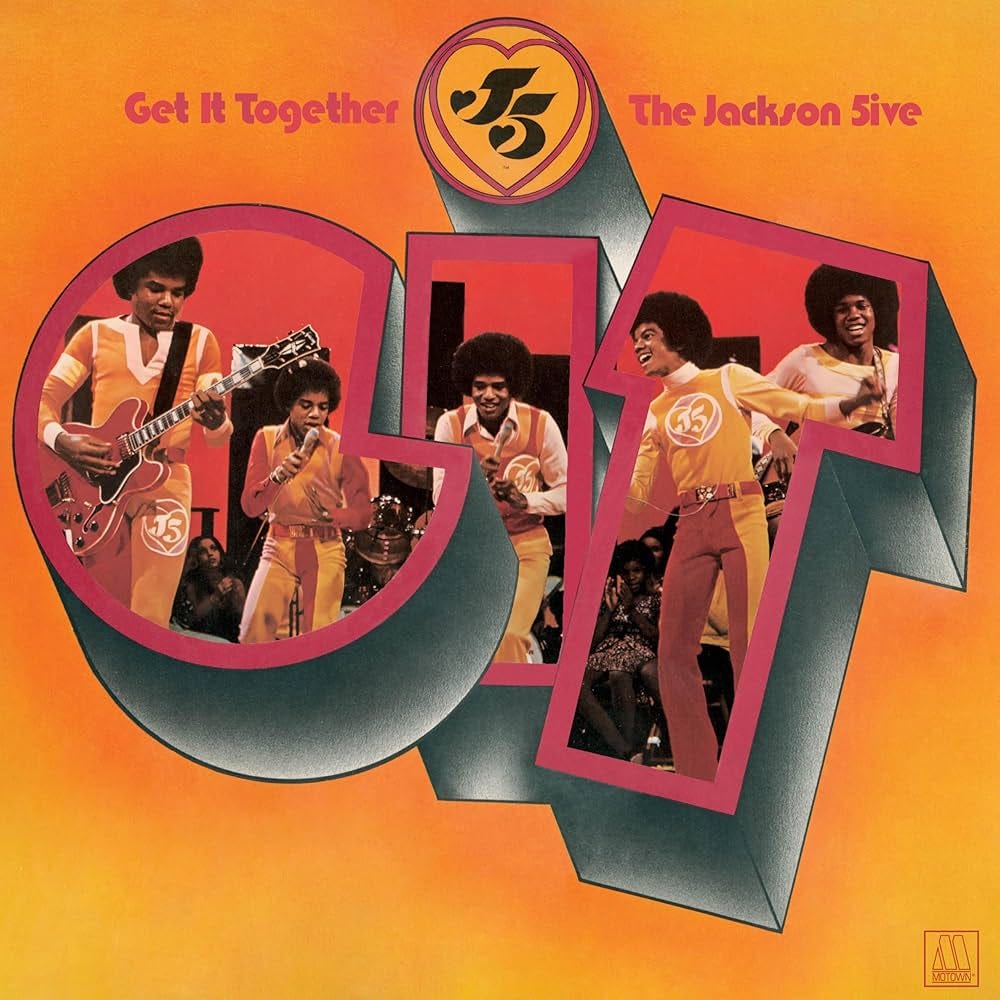

Get It Together (1973)

Possibly because Michael was in the thick of his voice change, this album arrived after a longer gap. With Hal Davis producing and the writing/production roster reshuffled, the group leans into arrangements that use choruses to cover for a Michael who can’t always deliver the same way yet. The addition of Norman Whitfield and others—fresh off the Temptations’ psychedelic run—strengthens their psych-funk side. There are more long tracks, more emphasis on instrumental sections, and far less of the “kids’ group” imprint. Whitfield’s involvement shows up on “Hum Along and Dance,” “Mama, I Got a Brand New Thing (Don’t Say No),” and “You Need Love Like I Do (Don’t You).” “Hum Along and Dance” has an early Funkadelic kind of sprawl, and the Undisputed Truth cover “Mama, I Got a Brand New Thing (Don’t Say No)” moves with real momentum. Even the Supremes cover “Reflections” gets a psychedelic tint. The single “Get It Together” only really connected on the R&B chart, but everything changed when they performed “Dancing Machine” on Soul Train—by 1974 it became a major hit. — p

Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3/5)

Psych-funk and longer forms start pushing the “kid group” image out of the room, with heavier grooves and more band-driven stretches. “Dancing Machine” is the obvious anchor, but the deeper tracks show them getting comfortable with darker motion.

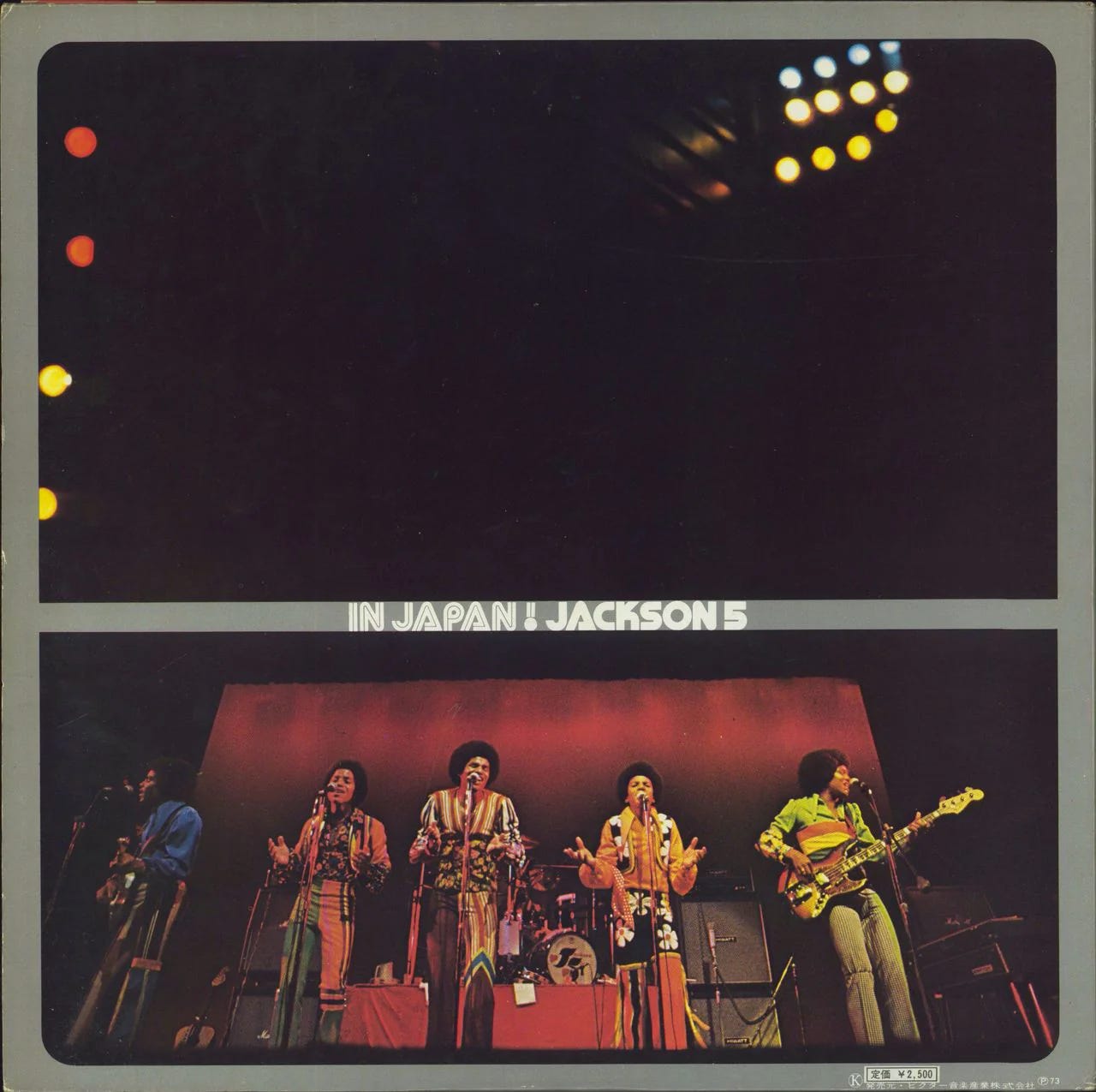

In Japan! (1973)

Recorded during their first Japan visit—guesting at the Tokyo Music Festival and then playing several standalone shows from late April into May 1973—this live album documents the Osaka performance and was originally Japan-only. Randy had joined the touring lineup on bongos, making them a six-piece. More than half the set is built around Michael and Jermaine solo material, and the covers lean funkier than usual: Rare Earth’s “Introduction”/“We’re Gonna Have a Good Time,” Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition,” and the Temptations’ psychedelic-era “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone.” The original liner notes (by Ken Miura) say that Michael—already in voice change—wanted to lower the key, but couldn’t due to “adult reasons” (likely logistics), and you can hear the strain right from the opening of “Lookin’ Through the Windows.” He tries to compensate by changing the melody, but it doesn’t fully solve it, and it cuts into the fun. That may also explain why some early hits aren’t included. It’s a valuable document, but a rare one that’s more frustrating than satisfying. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

A rare document of a difficult moment for Michael’s changing voice, which makes some parts tense to listen to. The payoff is hearing the group chase tougher, funkier material live, with a setlist that isn’t just the early-radio parade.

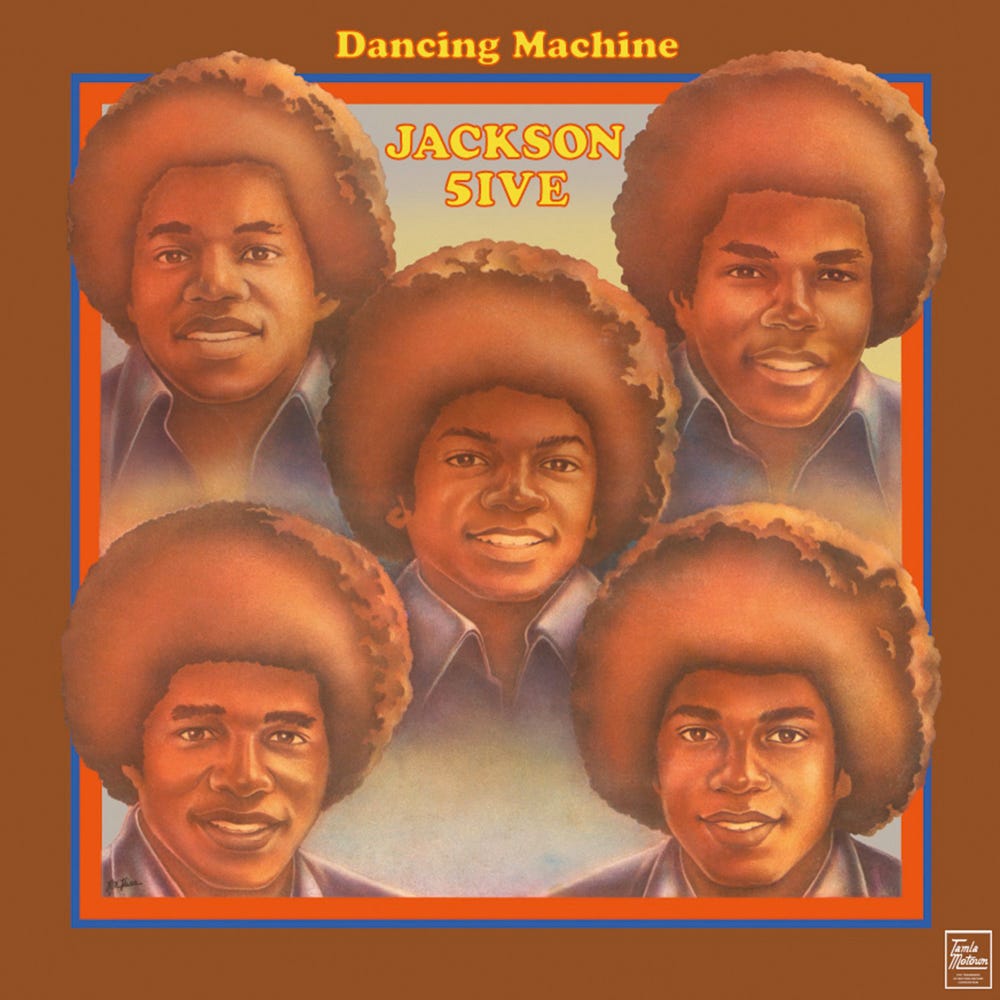

Dancing Machine (1974)

After “Dancing Machine” (first heard on the earlier album) finally became a huge hit and long-running seller, Motown built an album around it. The era’s funk emphasis continues, and they expand their bigger, more intricate dance tracks—especially the suite-like “I Am Love”—into a more production-forward style, not unlike what the Temptations were doing then. That shift effectively sidelines Norman Whitfield and even The Corporation, and the center of gravity moves to the Jerry Marcellino/Mel Larson team, with James Carmichael doing major work on arrangements. You can also hear the increased use of fusion-leaning session players; the Motown identity thins out. It’s their only studio album of 1974, as if everyone was waiting for Michael’s voice to fully stabilize. — P

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

The grooves are bigger and more intricate, with longer builds and more emphasis on band interplay than teen-pop sparkle. It can sprawl, but the best moments move with real physical force.

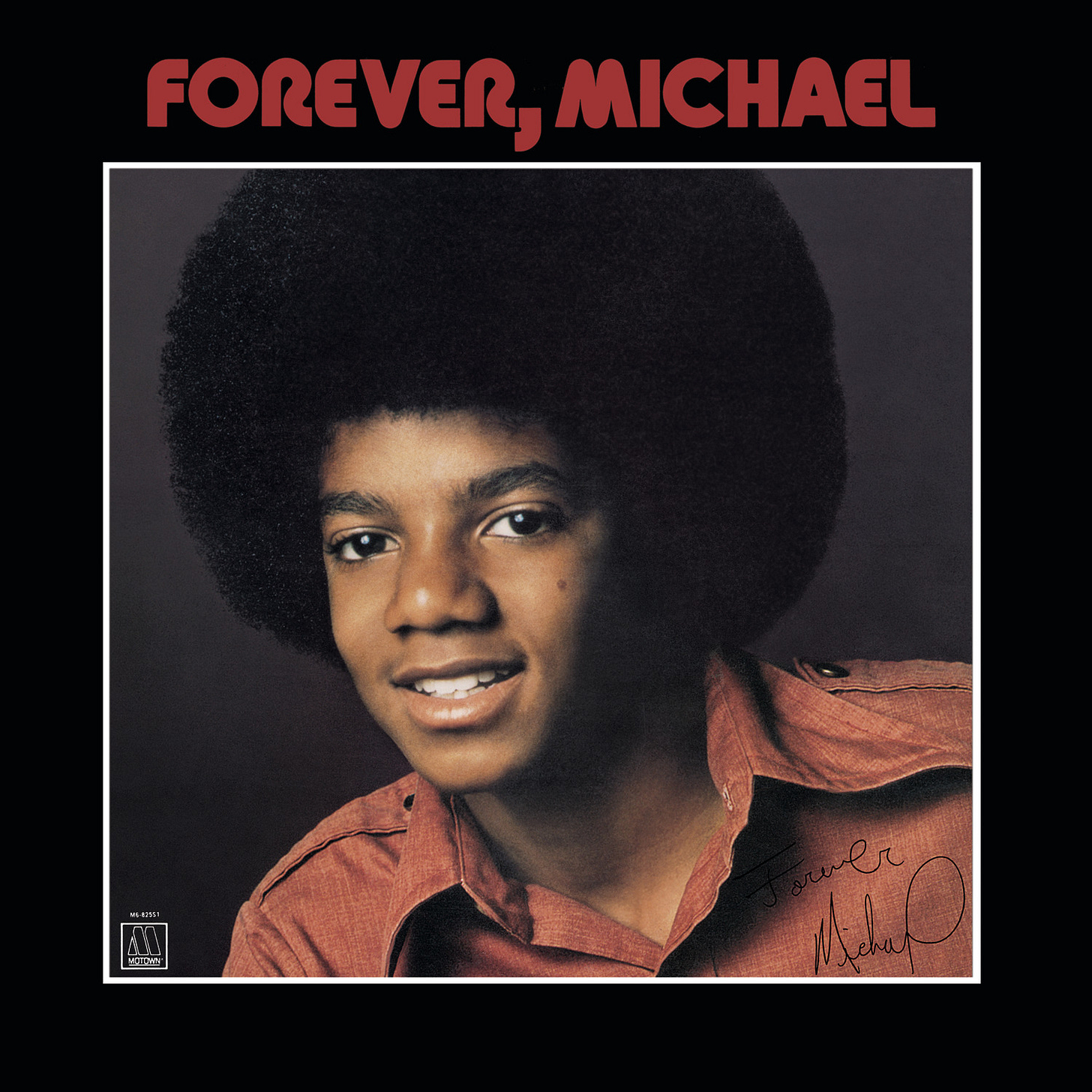

Forever, Michael (1975)

This was his final Motown solo album, and by now the voice change had mostly settled. You still catch moments where control slips, but the thickened low range sounds sturdier. With Holland–Dozier–Holland reconciled with Motown, Michael finally collaborates with them here: first on the opening single “We’re Almost There,” and also on “Take Me Back” and “Just a Little Bit of You.” The album immediately presents a more adult soul posture—no one is treating him like a kid anymore—and that tone stays consistent. It’s interesting that “We’re Almost There” reached the pop Top 10, while “Just a Little Bit of You,” which retains more of the old Motown imprint, did better on the R&B chart. Still, “Just a Little Bit of You” sounds slightly awkward for him to sing, so whether it was to protect his throat or to sound like a farewell, the album leans soft, and the overall effect is a little too airy. — P

Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3/5)

The voice change is mostly settled, and the album finally puts him in songs that assume he can handle grown-soul weight. It runs soft overall, but the best tracks show a thicker tone and more authority than anything earlier.

Moving Violation (1975)

This was their last Motown studio album, released just before the move to Epic. Holland–Dozier–Holland (including individual contributions) are involved in more than half the record, bouncing between the bright single “Forever Came Today,” the disco-leaning run of “Moving Violation,” “(You Were Made) Especially for Me,” and “Honey Love,” and the Stylistics-type Philly smoothness of “All I Do Is Think of You.” Michael Lovesmith handled the vocal arrangements, and one noticeable effect is how polished the choruses are, especially on “Forever Came Today.” Elsewhere, there’s a funk collage that drops recognizable riffs (“Body Language (Do the Love Dance)”), a Brazilian-ish sway (“Breezy”), a guitar-feature track (“Call of the Wild”), and even a sci-fi soundtrack tint (“Time Explosion”). It reads like an attempt to go out in style, but between the disco focus and the grab-bag ambition, it also feels scattered. Michael’s leads are still relatively limited—choruses carry a lot of the weight—and while his new voice is forming, it’s not fully locked in yet. — P

Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3/5)

A “one album, many directions” finale that flashes disco drive, Philly glide, and funk collage without fully locking into one identity. The choral work is unusually polished, and you can hear Michael’s new voice taking shape in real time.

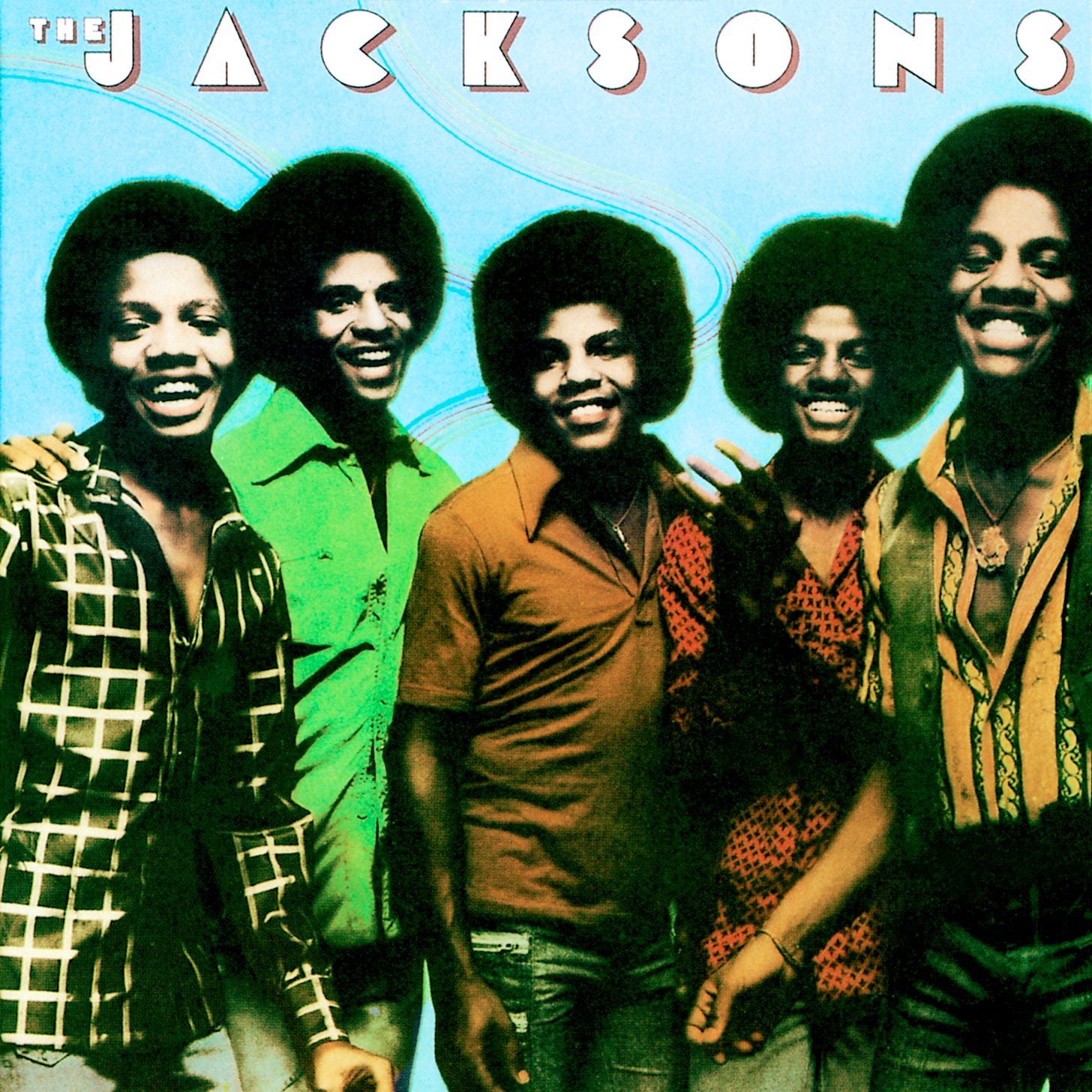

The Jacksons (1976)

With Gamble & Huff brought in as producers for their first release after leaving Motown, the group’s bid for creative control came with major consequences: legal issues forced a name change, and Jermaine’s departure followed. Still, the move also created real opportunities—Michael had direct access to Gamble & Huff’s songwriting methods, and that education matters later. He’s credited as a writer on “Blues Away” and “Style of Life.” The standout on that front is “Blues Away,” a bright, clean midtempo he wrote alone; he later joked that it was something he could listen to “without blushing.” The hit was “Enjoy Yourself,” which preserves a lot of the Motown-era spark, but the record’s strongest payoff comes when they fully commit to Philly form on songs like “Show You the Way to Go,” “Living Together,” and “Dreamer.” — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Philly craft tightens the group into cleaner lines and deeper pocket, and the singing sits more naturally in adult ranges. The biggest impact is hearing them step into a new kind of polish without losing their rhythmic edge.

Goin’ Places (1977)

They brought Gamble & Huff back and finished the next album in under a year. It’s the weakest seller in the Jacksons discography, but it’s also a quietly rewarding one: the lively, dance-leaning “Goin’ Places” plays well against the mellower Philly manners of “Even Though You’re Gone” and “Find Me a Girl.” The self-written songs are “Different Kind of Lady” and “Do What You Wanna,” and both land—“Different Kind of Lady” even became a single—but it also meant that the members only truly controlled two tracks. The imbalance clearly bothered them, and Michael later said that the stronger, ideology-forward “message” angle in Gamble & Huff’s material wasn’t really theirs. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

A strong push-pull between upbeat dance cuts and mellow Philly ballads gives it a quiet replay value. The frustration is that the group’s own authored material is limited, even though the band chemistry is clear.

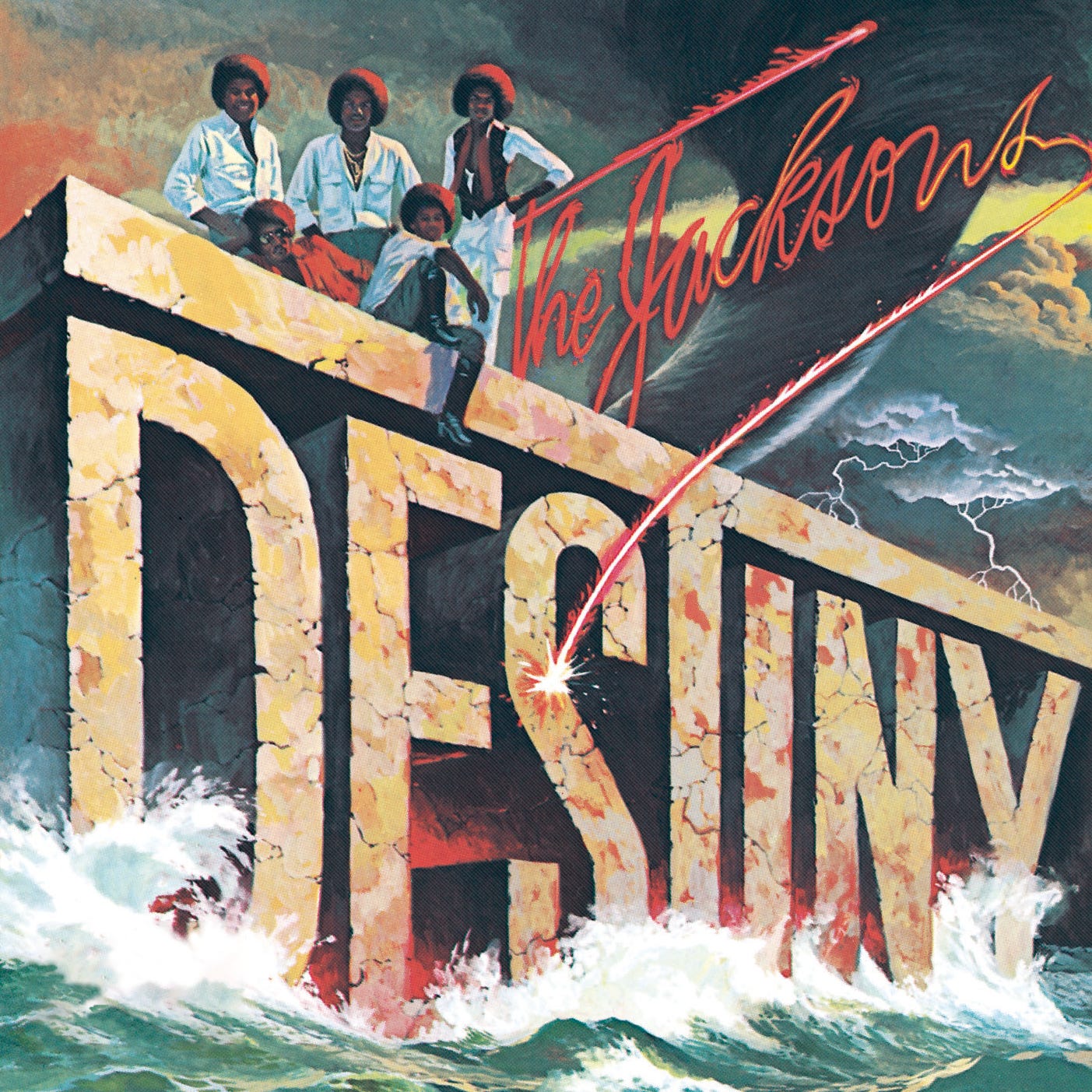

Destiny (1978)

After leaving Gamble & Huff, they formed Peacock Productions (a name Michael came up with, comparing their bond and versatility to a peacock’s feathers) and finally made the album they’d been pushing for: fully self-produced. They wrote everything except “Blame It on the Boogie” (which is precisely why it’s the one true outlier in authorship). “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground)” became their first U.S. Top 10 hit since “I Want You Back,” and the album went platinum—proof that they could manufacture a hit under their own control. It’s also loaded with early clues for what would soon happen on Off the Wall: the rhythmic DNA of “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground)” sits close to “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough,” and players like Paulinho da Costa and Greg Phillinganes strengthen that continuity. The record’s quiet peak is “That’s What You Get (for Being Polite),” a mellow classic Kid Capri used to play often. Michael later described it as a song where he admits he had the same doubts and anxieties as other high-teen kids, which makes it an early, direct statement of the loneliness that comes with being famous too young. — P

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Self-production gives them a tougher identity. It’s the moment they start sounding like architects of their own sound, not just performers inside someone else’s plan.

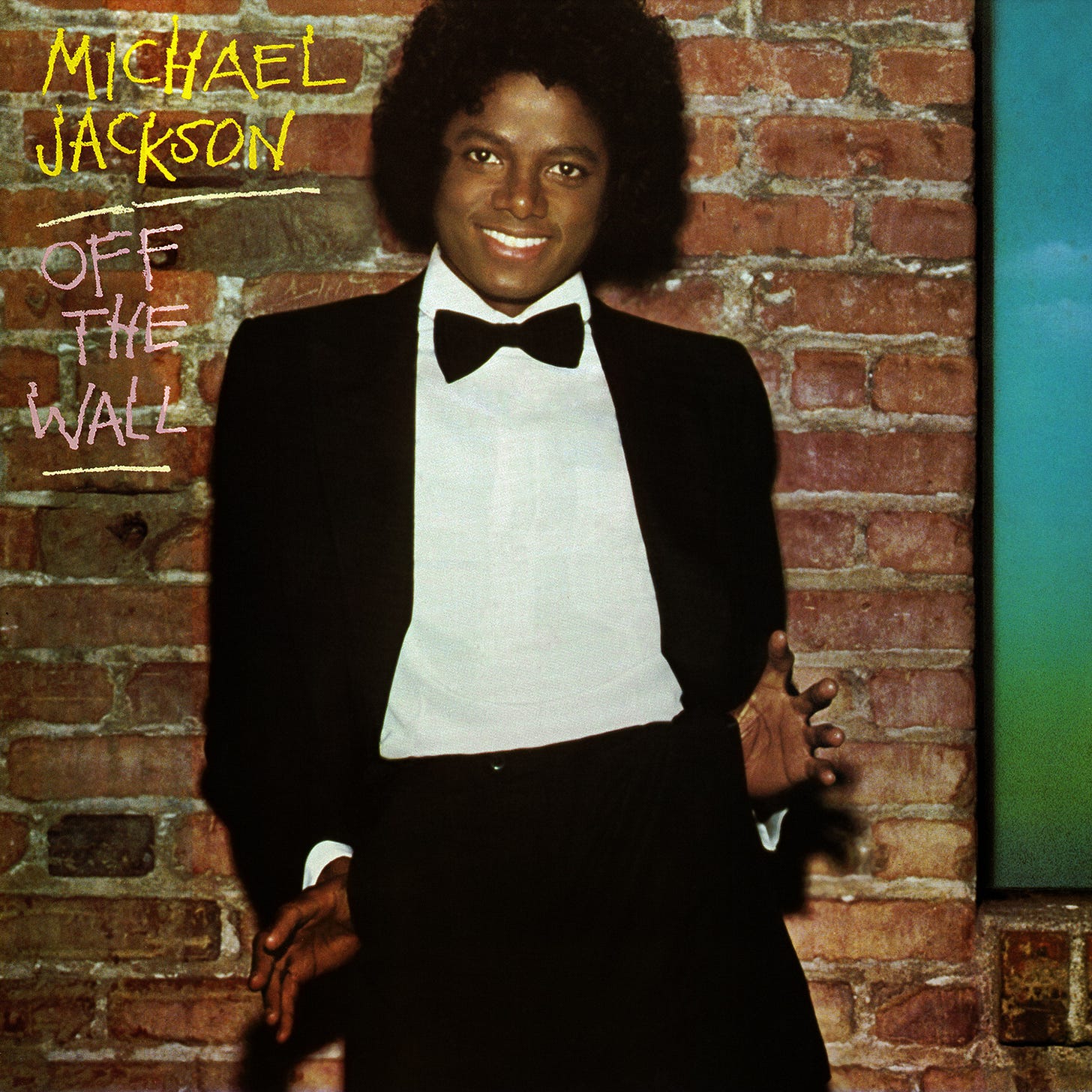

Off the Wall (1979)

Epic’s first solo release for Michael was his first solo album in roughly four years since the Motown era, and in practical terms it was his first real “artist album,” made with the mindset of creating a coherent work. Quincy Jones produced it. After first working with Michael on the film The Wiz, Quincy understood him as a performer and as a person. Michael’s long-term goal of complete independence as a solo act required one non-negotiable condition: the first album had to succeed. Convinced of dance music’s potential and already looking toward a much wider arena, Michael met Quincy—who was eager to plug into what was happening in the music scene—and the point where their aims clicked is this album, Off the Wall.

At 21, Michael also needed to project more than “former child star.” Put plainly: sex appeal mattered, and it’s a classic dance-music tactic. The songs Michael wrote on his own, “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” and “Working Day and Night,” and Rod Temperton’s “Rock with You” all carry that charge. Michael’s vocal shapes those ideas with flexibility and groove and gives “sexy” a different kind of weight. At the same time, on Stevie Wonder’s “I Can’t Help It” and the stage-standard ballad “She’s Out of My Life,” he shows a high-level, fully adult kind of love song performance. The sound and the singing were both contemporary and forward-tilting: the percussive drive and Brazilian accents being developed by Earth, Wind & Fire and Chic, Temperton’s melodic instincts (and the design sense of his band Heatwave), obbligato lines and refrains that answer the melody (whether pushed by Quincy or by Michael’s own ideas), Bruce Swedien’s precise mixes, the clean beauty of Philadelphia soul Michael had absorbed with the Jacksons, and the real on-the-floor instincts he’d learned through disco.

Over it all: Michael’s uniquely sharp lead vocal and background stacks. It’s a masterpiece that uses dance music as the spine, but makes everything function outward, as pop, an urban Black fusion at the cutting edge. The luxurious weight that multitrack recording can create also fit the moment, generating an excitement that could stand next to, and even outdo, the previous year’s Saturday Night Fever phenomenon. It unmistakably points to “what’s next,” and in the most literal sense it’s off-the-wall: unexpected, out of category. At the same time, it sits clearly in the soul-to-funk line, and that rootedness is part of what makes it shine. — P

Rating: ★★★★★ (5/5)

Off the Wall is built on elastic bass-and-drum pocket, bright horn punctuation, and a vocal that moves between bite and silk without losing the groove. Even when the ballads slow the pulse, the singing stays physical and precise, and the dance cuts (“Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough,” “Rock with You”) set a new standard for how cleanly funk can cross into pop.

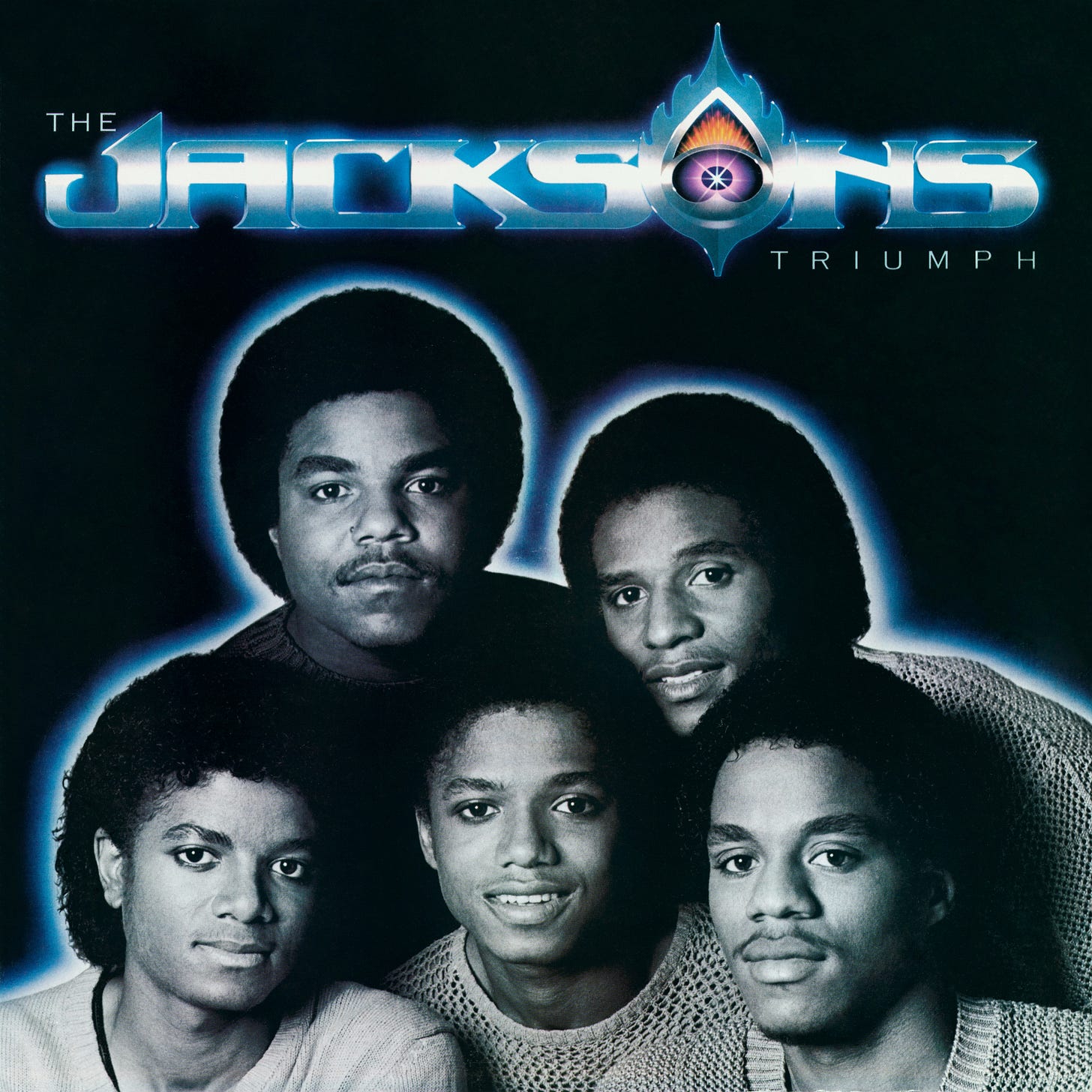

Triumph (1980)

This was their first album where every track includes a member songwriting credit, and they also continued producing the whole thing themselves. They started working on it right after finishing Off the Wall, and you can hear what Michael learned by working with Quincy Jones embedded in the arrangements. Even the personnel choices—Michael Boddicker and Greg Phillinganes handling synth roles—make it feel continuous with Off the Wall. Michael’s solo-written “This Place Hotel” plays like a bridge between the restless dance focus of Off the Wall and the darker, more paranoid storytelling that shows up later. The stadium-rock posture of “Can You Feel It” points toward “They Don’t Care About Us,” and the album’s lone ballad, “Time Waits for No One,” foreshadows the humanitarian sweep of “Heal the World” and the directness of “Gone Too Soon.” For listeners who only know Michael’s solo work, this may be the most immediately familiar Jacksons album. — P

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Big, confident pop-funk built around Michael’s growing bite as a vocalist, with enough edge to keep the sheen from going flat. Even the softer moments feel intentional, and the group doesn’t sound like background to his stardom.

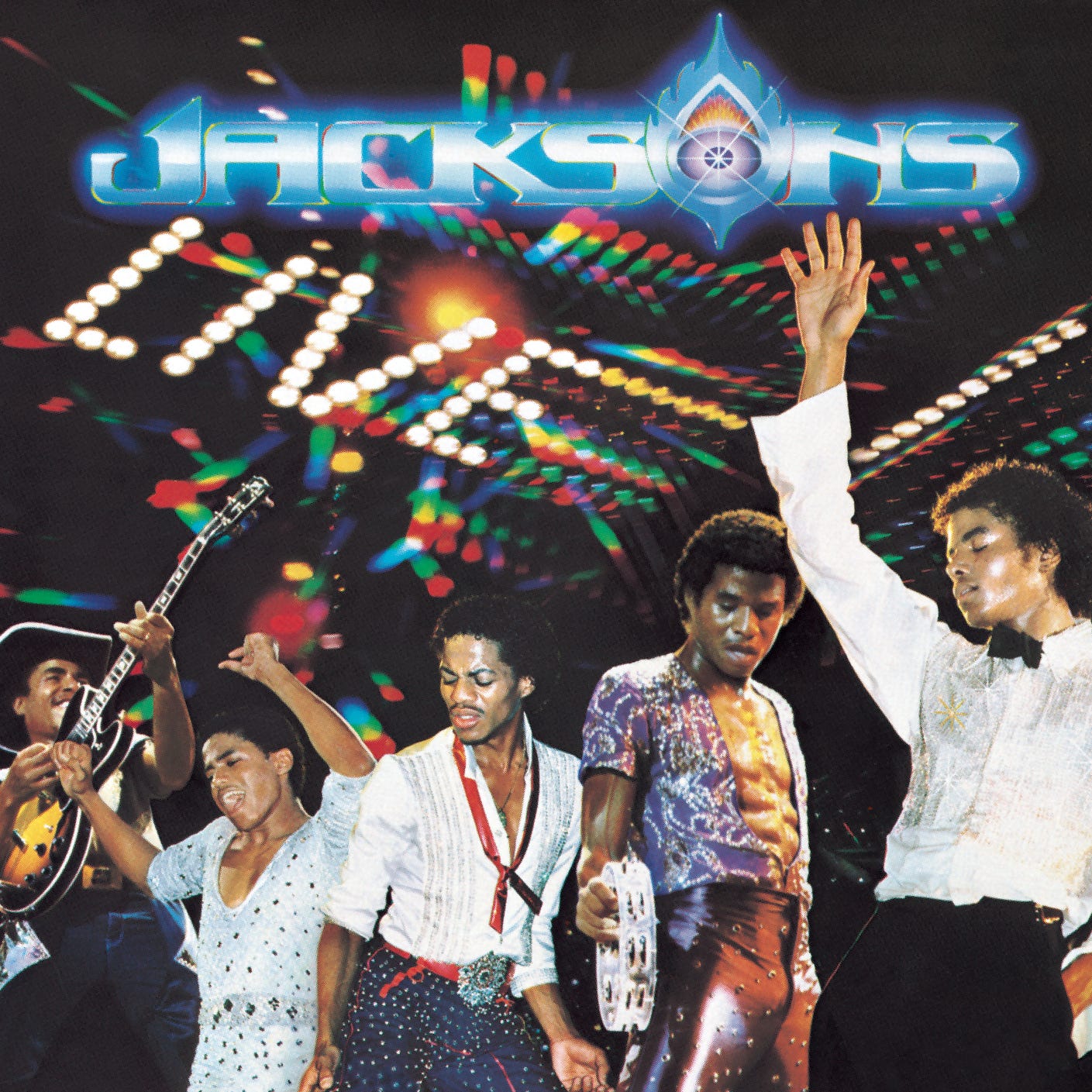

Live! (1981)

This is the Jacksons’ only live album, capturing the Triumph Tour (34 cities, 39 shows across July–September 1981). The performances and crowd response are both first-rate, and the set list is genuinely fun: it runs from the Jackson 5’s No. 1 run into then-current Triumph hits like “This Place Hotel” and “Can You Feel It.” The central value, though, is the five-song block from Off the Wall. The second “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough” begins, the screams spike, and “Workin’ Day and Night” is even better—starting from a percussive, vocal-led ramp and then breaking open, like the band is being pulled forward by Michael’s momentum. It’s an unusually direct document of him right before Thriller. — P

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

A high-energy document where the band is tight, the vocals cut through chaos, and the setlist shows their full evolution in one run.

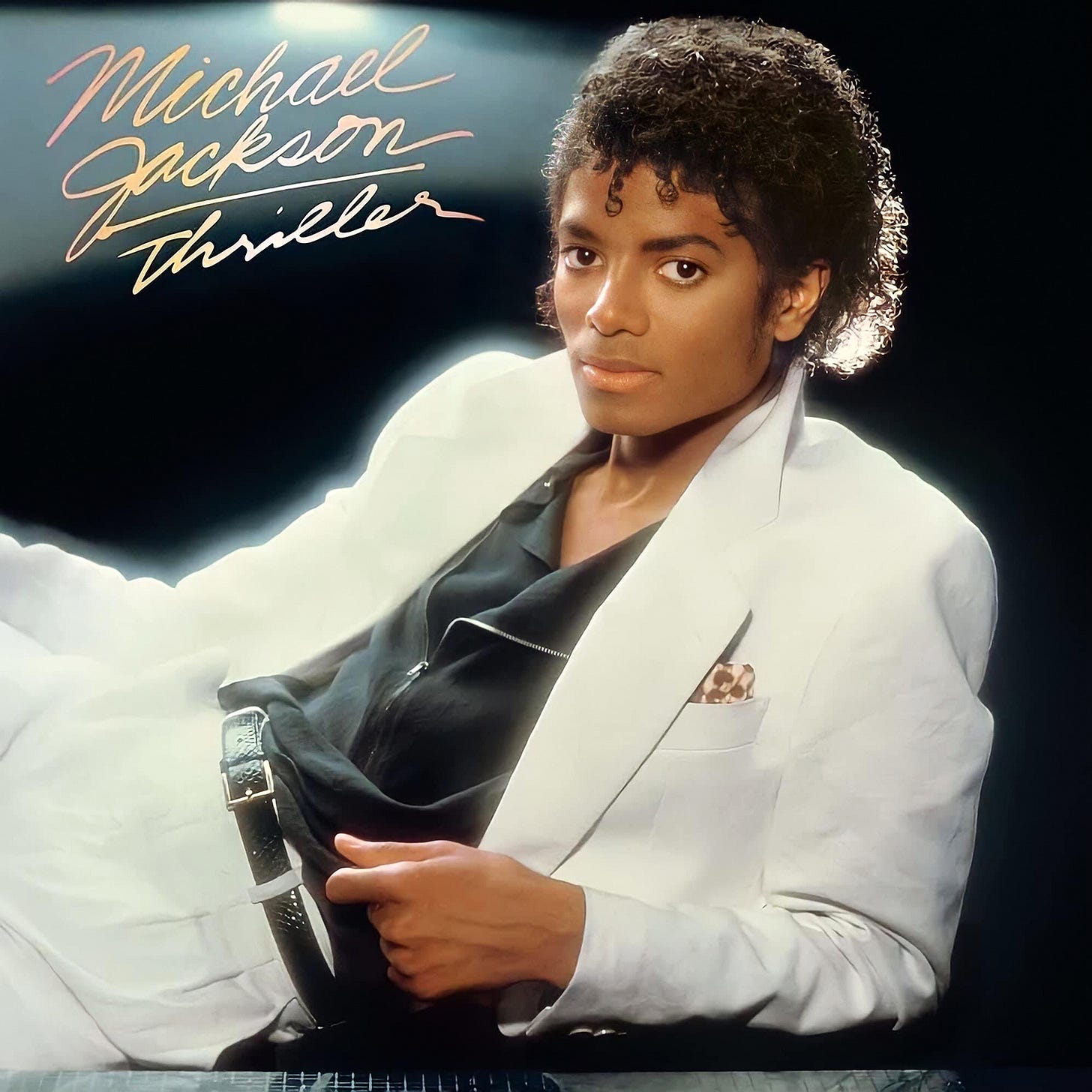

Thriller (1982)

Commercially, Off the Wall was a major success, but it won only one Grammy, and that disappointment hit Michael hard. Wanting to accelerate his push beyond genre boundaries, he turned immediately toward the next album. Quincy Jones—fully aware of how difficult that move was in the market—seems to have supported Michael’s ambition while also steering it with restraint. With that slight temperature gap between them, they reunited around a single objective: top the previous album. What they made was miraculous. Overlapping with the production schedule of what you could call Michael’s “shadow album,” the E.T. Storybook, Thriller was built on an unusually tight timetable. Near the finish line, they went through the extreme step of redoing all editing and mixing from scratch, and it still arrived with quality and impact that easily surpassed Off the Wall.

Even the huge early hit Michael wrote and sang with Paul McCartney, “The Girl Is Mine,” feels small next to how single-ready the entire tracklist is. The songs remain, at base, an extension of Off the Wall, and none of them abandon Black-music form. But the upgrades are undeniable. Vocals and sound gain a scale and intricacy that goes beyond “gorgeous,” and there’s also an ease and playfulness in the details that keeps it from reading like a pure hit-chase; it holds together as an album. Compared with Off the Wall’s broad, varied musician roster, this record uses a more compact, elite team (including members of Toto in select spots), with keyboard director Greg Phillinganes and arranger Jerry Hey especially prominent. More than anything, Michael’s growth is startling: voice (including his signature voice-percussion), sound design, and songwriting all bloom.

It’s most obvious in his own songs “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’,” “Beat It,” and the cold, mysterious grip of “Billie Jean” is beyond normal scale. “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” and “Beat It” also function as an early chapter in the “beyond-genre” direction that would be fully realized on Bad: the former through its words, the latter through its sharp-edged sound. Alongside them, “Baby Be Mine,” the now-standard “Human Nature,” and the enduringly beloved “The Lady in My Life” all lower the wall between categories. Of course, the album’s unmatched success (more than 100 million sold worldwide in total) can’t be separated from the music-video revolution—built through “Billie Jean” and “Beat It” and made definitive by “Thriller”—or from the moonwalk’s cultural shockwave that began with “Billie Jean.” Even if you strip away the visuals, though, Thriller remains a crucial turning point for Michael. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★★ (5/5)

Thriller tightens sharper hooks, harder rhythmic snap, and a vocal performance that sells character as much as melody (“Billie Jean,” “Beat It”). The sequencing never drifts because each song has its own chassis—funk, rock, synth-pop, quiet storm—yet the album still sounds like one controlled world.

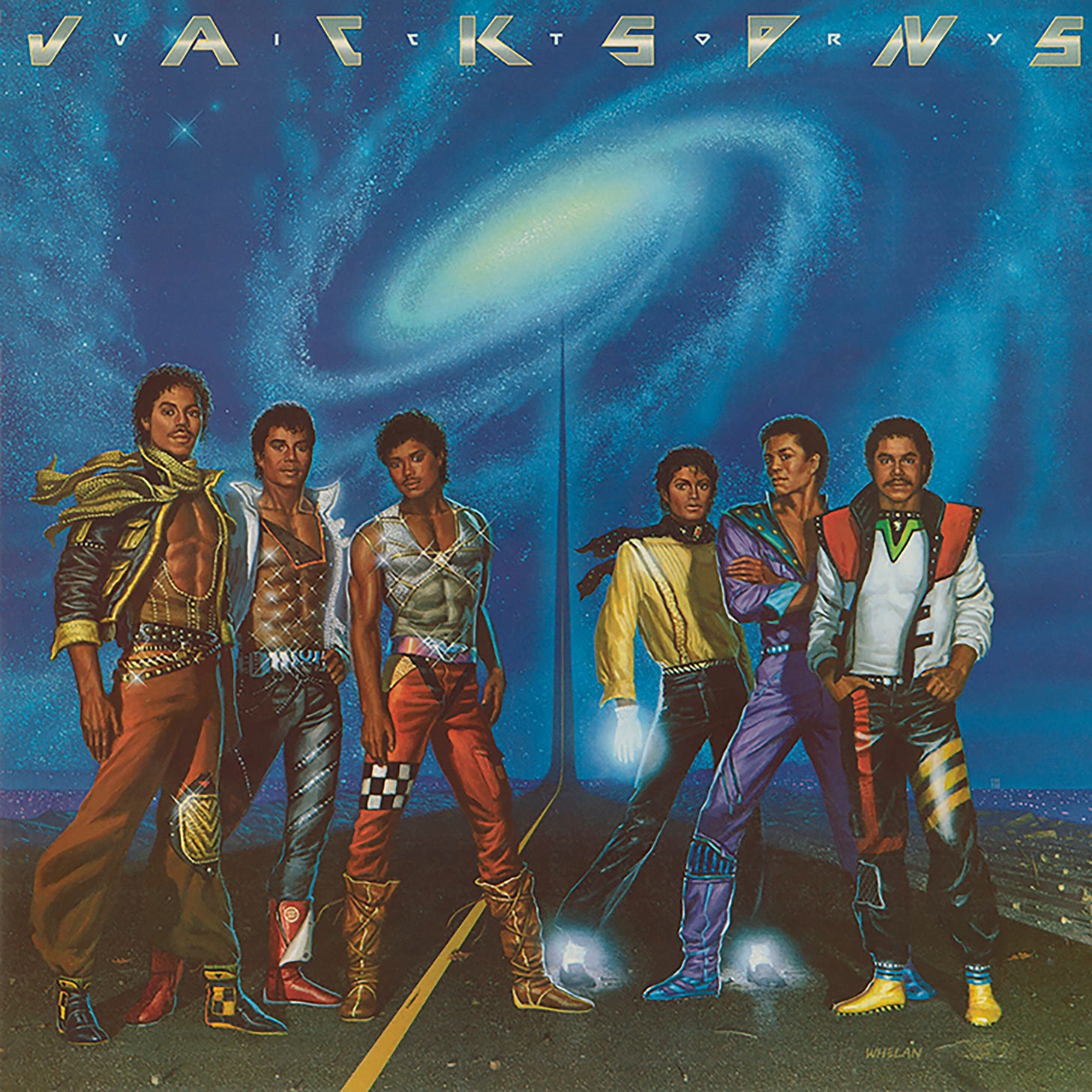

Victory (1984)

Released while the Thriller frenzy was still in full force, this became the first and last album to officially unite all six brothers again, Jermaine included. The personnel borrows heavily from the Thriller world—Steve Lukather, David Paich, Jeff Porcaro, Louis Johnson, Paulinho da Costa—but because it’s basically a pile of member submissions assembled into one LP, the internal unity is thin. “The Jacksons’ White Album” might be overstating it, but there is a real unpredictability to it. Michael takes lead on three tracks: Jackie-produced hard-rock “Torture,” the Mick Jagger duet “State of Shock,” and the harp-tinted ballad “Be Not Always.” Randy takes the lead on “We Can Change the World,” where he’s also credited as a co-writer. — P

Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3/5)

A messy, fascinating group album where the range of styles is the point, for better and worse. Michael’s leads are the obvious centerpieces, but the real character comes from how unpredictable the album is from track to track.

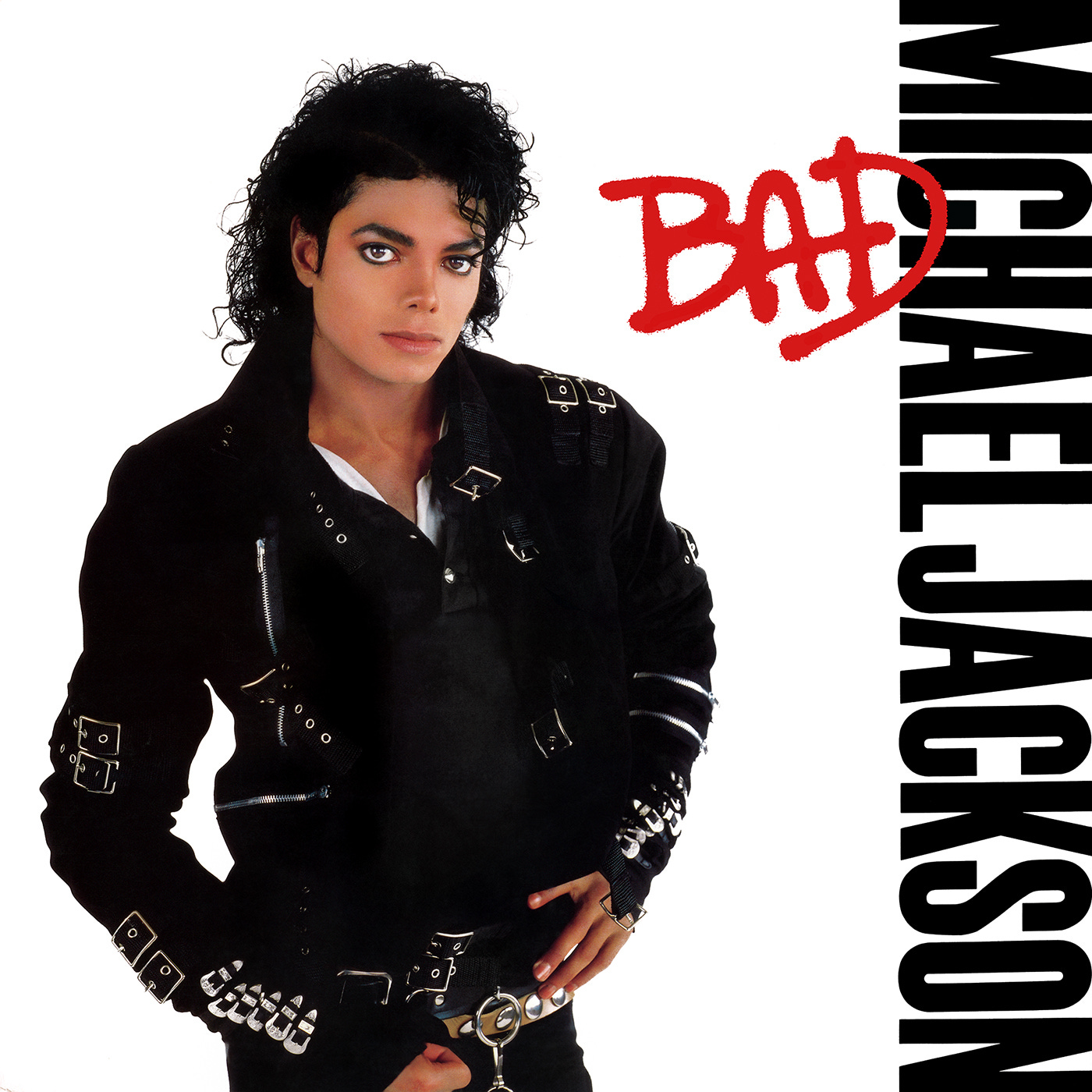

Bad (1987)

After Thriller’s mega-success—through the Jacksons’ Victory and the tour, Michael’s formal departure from the group, “We Are the World,” and filming Disney’s Captain EO—this becomes the final chapter of the so-called Quincy Jones trilogy. As I said in the Thriller section (and this is the author’s personal view), with Bad Michael became a singular artist who’s hard to confine to any one genre. Quincy still produced, but his weight seems noticeably reduced compared with the previous two albums. You could read this as Quincy sensing the rapid rise of hip-hop in the scene and feeling a kind of limit to his own approach. He actively sought out hip-hop talent, and he even tried to bring Run-DMC into Bad.

But at least at that moment, he likely hadn’t reached a deep, internal grasp of hip-hop’s core sensibility. On top of that, Quincy’s health suffered during Bad’s preparation due to ongoing overwork, which may have pushed even more responsibility onto Michael. The biggest reason, though, is probably simpler: Michael’s ability was already more than sufficient. The hard, sharp-edged funk sound Michael wanted could stand directly against hip-hop. Add strong ballads and midtempos and you have a complete package. Jerry Hey’s horns still bring flashes of a Quincy-like signature, but what sits under each track is essentially “MJ-ism.” In practice, apart from “Just Good Friends” (with Stevie Wonder) and the message song “Man in the Mirror,” Michael wrote everything himself, and the number of standout songs is enormous—good enough to rival Thriller (and it also produced five No. 1 pop singles, three more than Thriller). The title track “Bad” (which reportedly had Prince in the conversation at one point) and “Smooth Criminal” (which became a talking point through the film Moonwalker) are hard-line masterpieces that lean into Michael’s strengths.

The fierce funk-rock guitar track “Dirty Diana” also pulled in rock listeners. Quincy reportedly pushed to include the Captain EO song “Another Part of Me,” and it lands as one of the album’s most vivid moments. “Liberian Girl,” lightly dusted with exoticism, is another strong cut. The duet with Siedah Garrett, “I Just Can’t Stop Loving You,” is the long-awaited Michael-written ballad and one of his finest. And “The Way You Make Me Feel,” along with the sharp message song “Man in the Mirror,” taps a retro, finger-snapping R&B feel that Michael likely absorbed in childhood. Right after completing this dense record, he launched his first solo tour—starting in Tokyo and running for roughly a year and a half—drawing more than four million people. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★½ (4.5/5)

Bad is Michael leaning into the edge, with a run of singles that hit like clean punches (“Bad,” “The Way You Make Me Feel,” “Smooth Criminal”). It’s a long album with a few soft spots, but the best tracks lock into a hard funk-pop grammar that nobody else in 1987 could execute at that level.

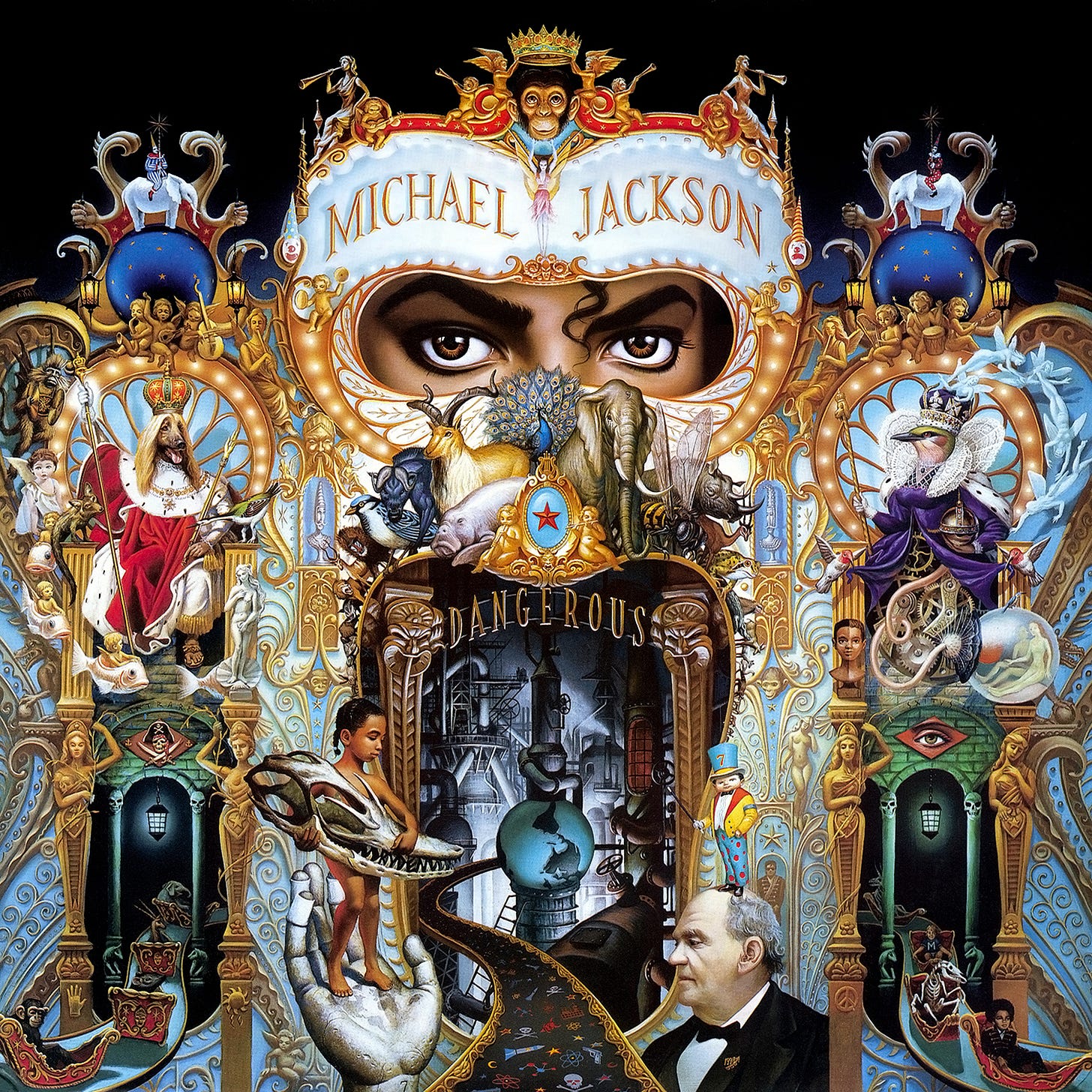

Dangerous (1991)

After the Bad tour, Michael was reportedly slated to release a best-of with several new songs. For reasons unknown, that plan was reworked, and instead he made a fully new studio album—possibly using some of the songs originally intended for that project, including the eventual smash “Black or White” and the title track “Dangerous” (according to one theory). For Michael, it was also the first album where he stepped away from Quincy Jones and took the production lead himself. He produced every track, wrote everything except “Remember the Time” and “Gone Too Soon,” and he also chose a co-producer nearly ten years younger: Teddy Riley. Teddy was the key creator behind the sound dominating dance floors at the time, New Jack Swing (NJS). He’d participated in the Jacksons’ 1989 album 2300 Jackson Street, but beyond that, Michael was likely energized by Teddy’s run with Guy and other productions, plus Janet Jackson’s blockbuster Rhythm Nation 1814 (Jam & Lewis), which shared the era’s forward momentum.

For updating Michael’s own hard-funk direction from Bad, Teddy was the right pick. On Dangerous, that update happens. The hard NJS of “Jam” and “She Drives Me Wild,” the stripped beat plus guitar bite of “Why You Wanna Trip on Me,” and the street-weight added cleanly in “In the Closet” and “Can’t Let Her Get Away” all fit as strong entries in Michael’s neo-funk lane. At the same time, Michael and Teddy also modernize the whispery dance approach heard on parts of Off the Wall and Thriller. The clearest success there is “Remember the Time,” which becomes a tall, mellow R&B cornerstone in Michael’s style. “In the Closet” (which reportedly had a Madonna duet plan at one stage) is another prize in that lane, defined by the hard contrast between its stripped early stretch and its melodic chorus. Michael stacked the Teddy-heavy material in the first half of the album, and it’s obvious he saw it as the spine, but the back half is strong too.

The catchy message song “Black or White” and the heavyweight rocker “Give In to Me” extend the funk-rock line that ran through “Dirty Diana.” The dark, percussive “Who Is It,” built through layered rhythm and vocal attack, stands out on its own terms. Slower songs are also beautiful: “Will You Be There” (well-known through Free Willy), the gospel-leaning “Keep the Faith,” and “Gone Too Soon,” later recorded by Babyface. The defining 1990s Michael ballad “Heal the World” is also a major message song, remembered alongside his iconic Super Bowl performance. You could hear the album as a two-part structure: the R&B/club side and the pop side. That split also suggests how consciously Michael was thinking about his position in the scene. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Dangerous splits its personality on purpose—hyper-percussive New Jack Swing up front (“Jam,” “Why You Wanna Trip on Me”), then broader pop and slow-burn drama later (“Will You Be There,” “Heal the World”). When it works, the rhythmic bite and the vocal ticks feel newly modern, even when the album’s scale sometimes pulls against its own focus.

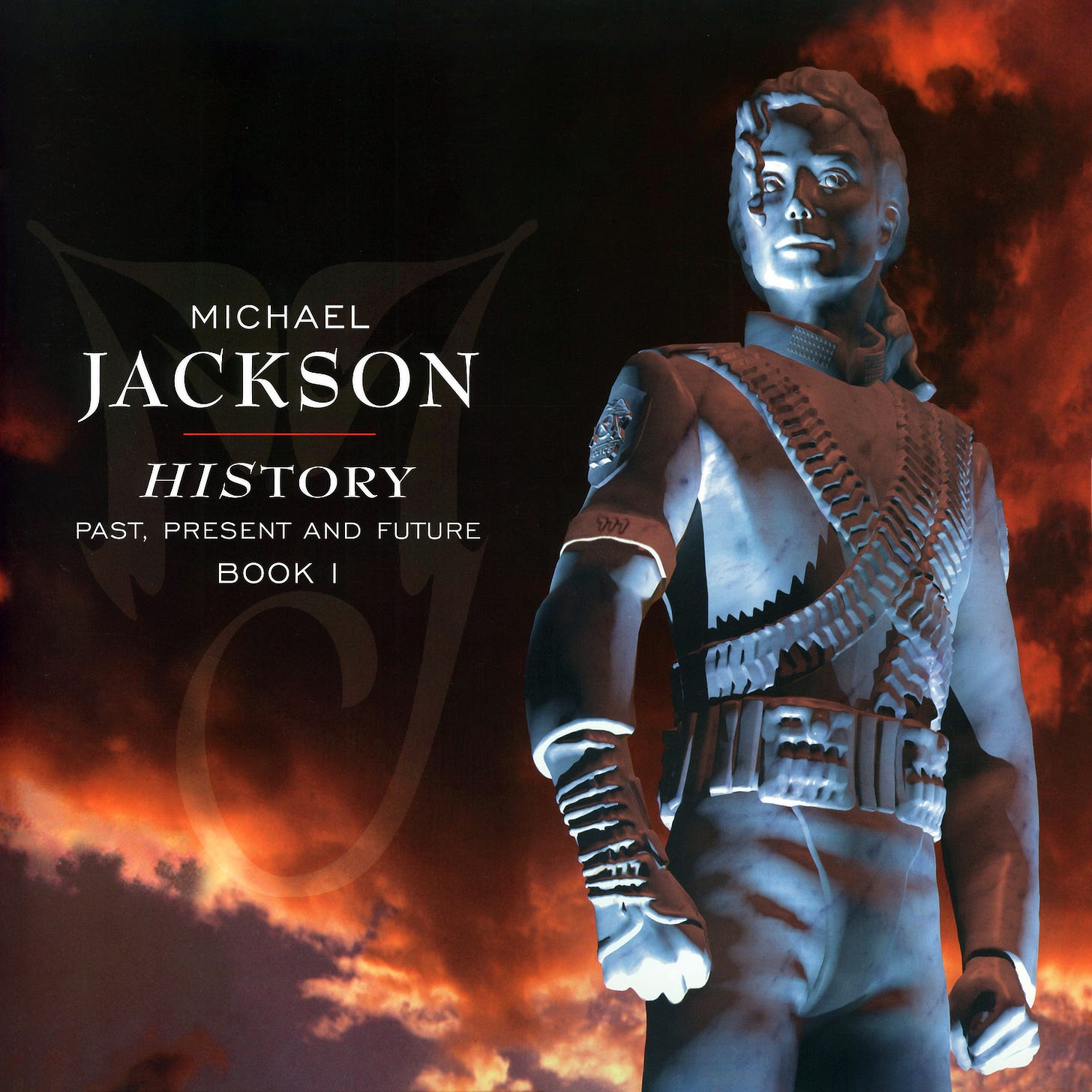

HIStory: Past, Present and Future Book 1 (1995)

This double CD is split into Disc 1, a best-of drawn from Off the Wall through Dangerous, and Disc 2, which collects new songs (including previously unreleased material). Here I’ll skip Disc 1 and focus only on Disc 2. Michael produced every track, but he produced only five alone; most are co-productions with people like Jam & Lewis, Dallas Austin, David Foster, and the Pissy Man. Other than the cover songs “Come Together” and “Smile,” and the Pee Pee-written “You Are Not Alone,” Michael wrote the songs himself. You can’t talk about this set without facing the 1993 child abuse allegations. In that period, Michael endured humiliating investigative procedures and nonstop media coverage. Several of the Disc 2 tracks feel so directly shaped by anger and grief from that experience that it’s hard to hear them as anything else. Some are almost too raw; if you don’t understand the context, it can be painful to listen while trying to gauge intent.

Still, the overall level is undeniably high again, and there are multiple songs here that deserve to be called classics. “Scream” (with Janet Jackson, and with Jam & Lewis in the room) and “They Don’t Care About Us,” which uses a rough beat to sharpen the words, are expressions of rage that still pull you in on musical force alone. “This Time Around,” made with Dallas Austin and driven by repetition (and featuring The Notorious B.I.G.), works the same way. “2 Bad,” with rap mixed into its structure, also functions as a statement while staying compelling as a track. On the other hand, the lonely mood of “Stranger in Moscow” is one of Disc 2’s most beautiful songs—its feel even overlaps with certain strains of progressive-leaning ambient music (and it’s said to trace back to game music Michael drafted).

Message-driven songs that should be heard apart from the scandal include the environmental anthem “Earth Song,” and the more peace-centered “HIStory.” And rather than anger or sorrow, compassion sits at the front of “You Are Not Alone,” the ballad that remains highly regarded. “Come Together” is a Beatles song Michael also performed in the 1988 film Moonwalker, but this version leans more acoustic. “Smile” is also a cover, originally by Charlie Chaplin (from the film Modern Times). Michael’s affection for Chaplin is well known, and Chaplin—along with Marcel Marceau, whom Michael knew—was a major source for Michael’s pantomime-style movement. Like “Come Together,” “Smile” feels strongly like tribute. “Childhood” (the theme from Free Willy 2), where he sings unusually frankly about his own youth, carries a similar tone; maybe it’s only my imagination, but Michael sounds more openly sentimental here than usual. — P

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Disc 2 of HIStory is Michael at his most exposed in tone: rage, paranoia, and exhaustion pushed into tight, hooky structures (“Scream,” “They Don’t Care About Us”). The highs land because the writing stays melodic even when the subject matter is raw, and “Stranger in Moscow” proves he could still make a quiet track feel enormous without leaning on spectacle.

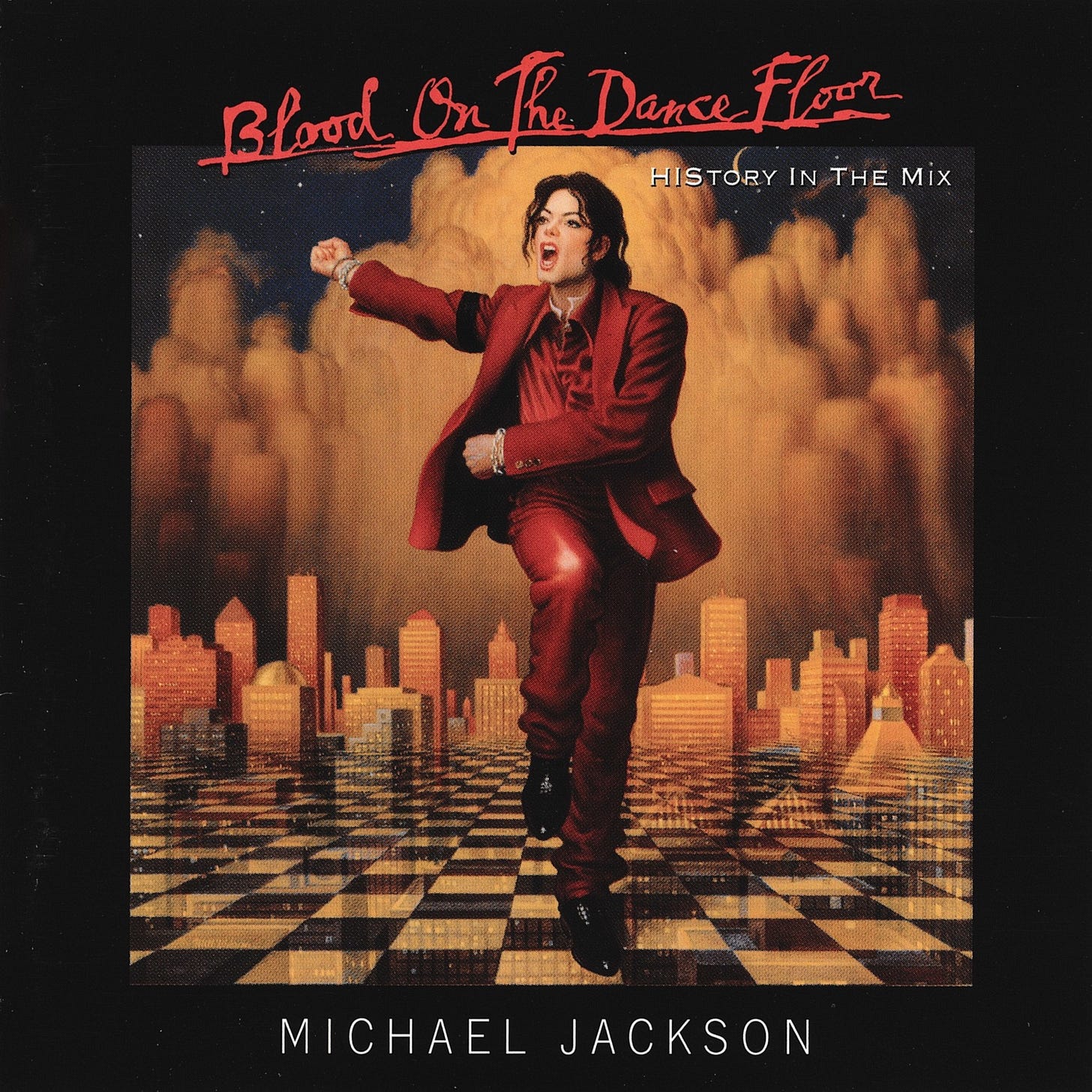

Blood on the Dance Floor: History in the Mix (1997)

A surprise release that functioned as a side project. In basic terms, it’s positioned as a remix collection for the HIStory era rather than a true original album, and it may have been rushed out quickly for contractual reasons. Still, it includes five new tracks and can’t be dismissed, and it became the best-selling remix album in history. Most of the new songs are believed to be Dangerous outtakes. Two Teddy Riley co-writes, “Blood on the Dance Floor” and “Ghosts,” don’t feel radically new, but they’re strong entertainment pieces: “Blood on the Dance Floor” mixes suspense with a sly sexual charge, and “Ghosts” pairs a “Jam”-like opening with a chorus that hits hard.

“Morphine,” where you can hear Slash’s guitar as on “Black or White,” sparked controversy because it names painkillers, but it’s also a genuinely inventive funk track (and Michael himself plays instruments like guitar and drums here). “Superfly Sister” is eccentric funk with aggressively erotic lyrics, and it strongly recalls Prince. The socially critical “Is It Scary,” which reads like a follow-up in theme and posture, is a Jam & Lewis track and is likely a HIStory outtake (and “Ghosts” may also date to that period lyrically). The remix set in the second half includes heavily reworked versions, and reactions will vary. Still, the track where Jam & Lewis make it sharply funk by using the same Sly sampling move they used on Janet is a real achievement, and some of the mixes with a distinctive coolness are also outstanding. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Blood on the Dance Floor is half new material that leans into speed, menace, and sex (“Blood on the Dance Floor,” “Ghosts”), half remixes that range from disposable to genuinely reimagined. The new tracks justify the project because they hit with real rhythmic urgency, even if the package as a whole is uneven by design.

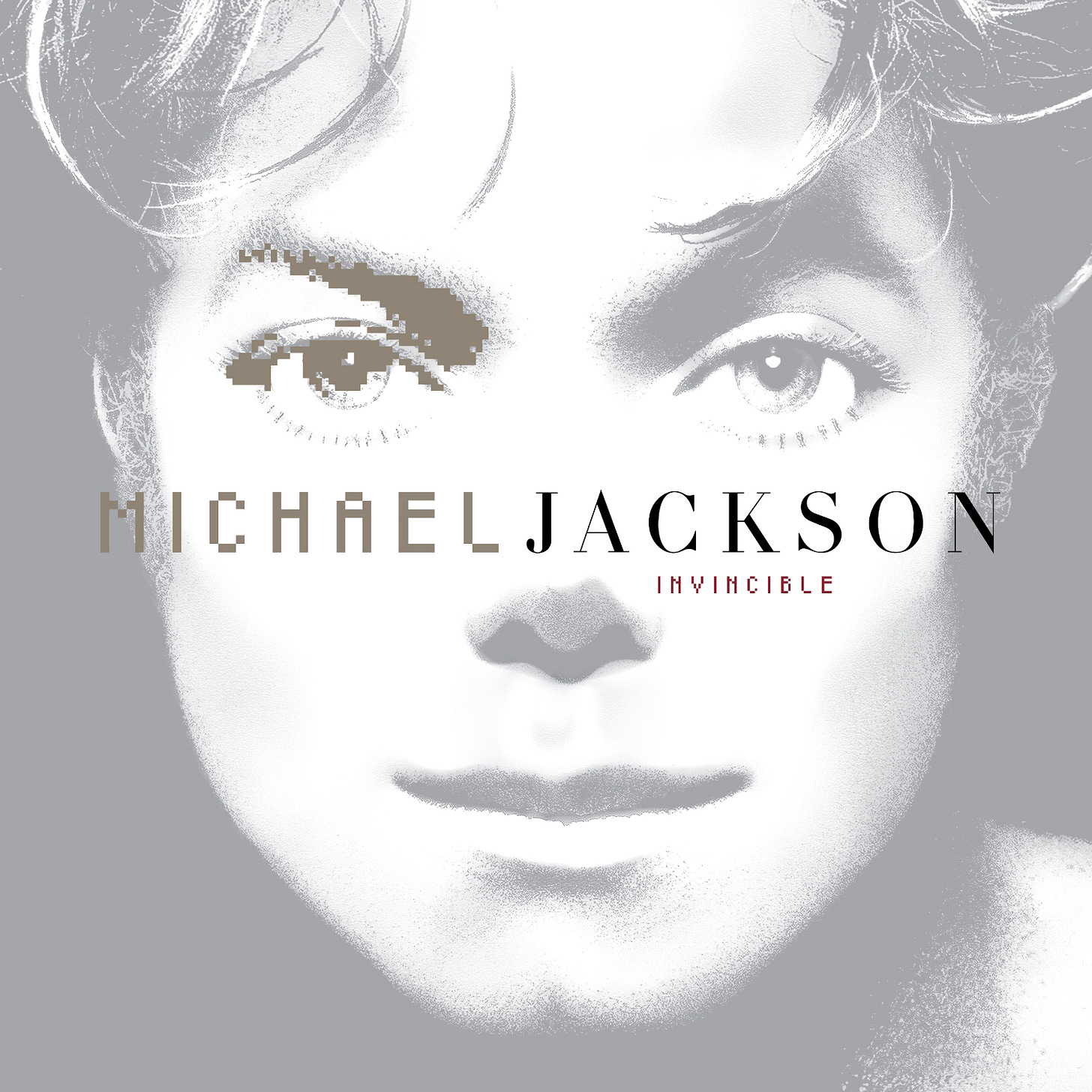

Invincible (2001)

Titled with words meaning “unshakable” or “invincible,” this was Michael’s first original album in six years. In sound, lyrics, and vocal approach, you can hear that he settled in and worked carefully, and it also shows major differences from his earlier albums. Of the 16 tracks, 14 are co-produced with R&B creators; Michael produced only two alone. Broadly, you could say the pop-leaning material that made up a large share of Dangerous is replaced here with R&B-leaning midtempo and slow songs, pushing the whole album closer to an R&B base. Fans expecting more pop might feel some frustration, but even when it’s R&B-coded, the melodies still carry Michael’s signature, and the album is consistently full, with many strong songs. The central figure is Rodney Jerkins, already firmly established in the R&B scene. Teddy Riley—Rodney’s mentor—also contributes four tracks, and together they handle ten of the album’s songs (both also worked on releases for Michael’s MJJ label).

Rodney largely delivers the sharper, catchier, near-future songs: the hit single “You Rock My World,” plus “Unbreakable,” “Heartbreaker,” and “Invincible,” which lock into a hard, forward sound. Teddy leans more toward mellow: the pure-love song “Heaven Can Wait,” the Babyface-like ballad “Don’t Walk Away,” and “Whatever Happens,” where Spanish guitar deepens the emotion (with Santana joining). Babyface himself participates on a Michael album for the first time, and since their vocal tones share similarities, the acoustic slow track “You Are My Life” fits naturally. Following his role on HIStory, Pissy Man shows his presence in the second half with the heavy message song “Cry.” Among those major names, other highlights include the neo-Philly lane of “Butterflies” and Michael’s work with the mid-career fixture Dr. Freeze on “Break of Dawn,” both of which earned strong respect from the R&B side of the aisle. Michael’s two solo-produced songs, “Speechless” and “The Lost Children,” are clear and plain, with a simple emotional grain; it may sound like an odd comparison, but they can even suggest the touch of Irish folk song in the way they sit.

Michael sounds noticeably different here than on HIStory: the lyrics feel less wrapped in surface reaction and more aimed at essentials, and his voice itself seems slightly changed, with moments that sit closer to his natural speaking tone, which can read as more direct. It’s a substantial album, and it also hints at a new Michael style. That’s exactly why it also feels like an unfinished final statement. — P

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Invincible plays like a late-career R&B record with pop power tucked inside it—more midtempo weight, more intimacy, fewer obvious left turns (“You Rock My World,” “Butterflies”). It doesn’t have the streaking momentum of his ’80s peaks, but the best songs give you a mature, grounded Michael whose phrasing sits deeper in the pocket than people credit.