The Jackson 5 Follower Groups Before 1994

The Jackson 5 template proved too profitable to retire. Family harmony meets youth marketing. These nine albums trace the Jackson 5’s afterlife in boardrooms and bedrooms.

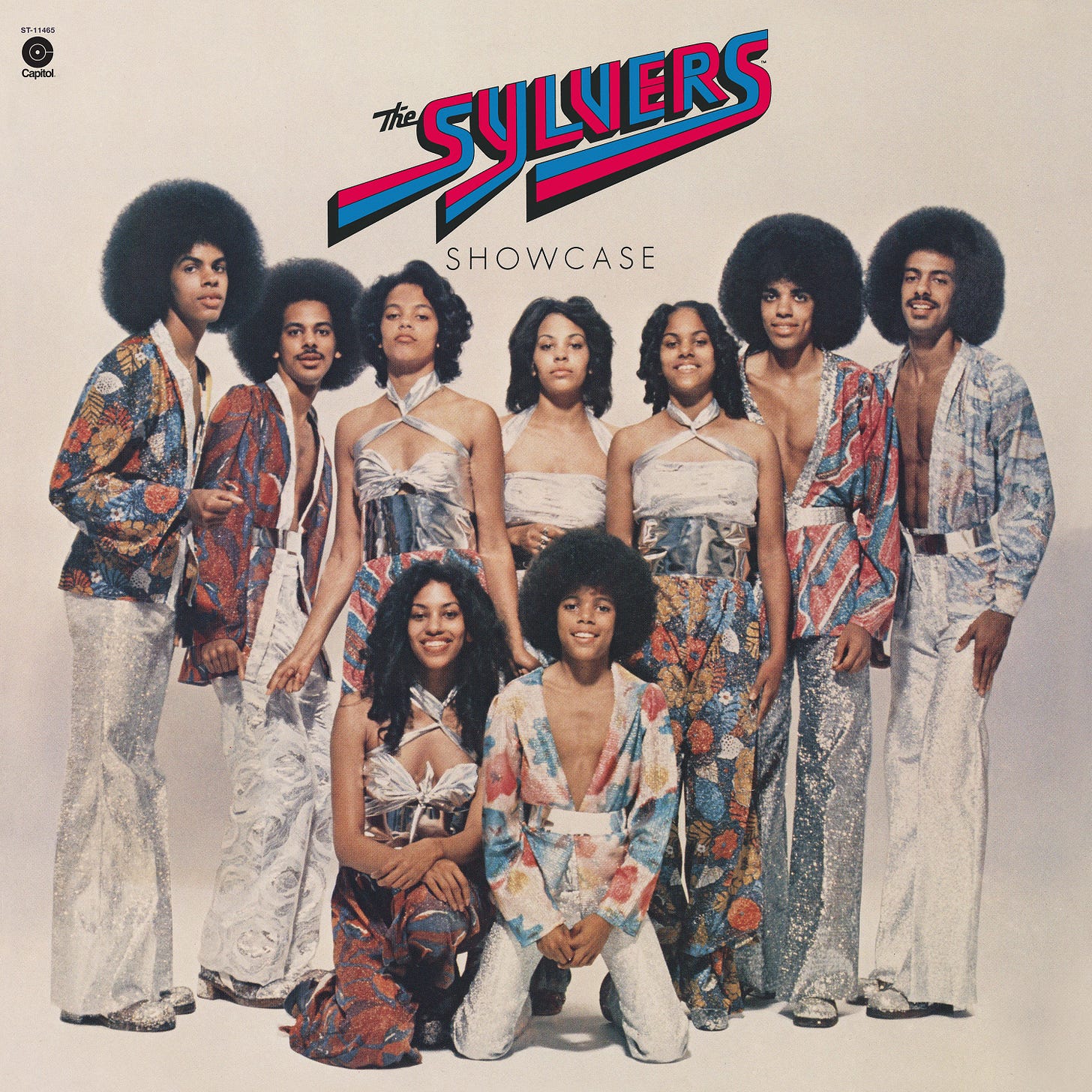

The Sylvers arrived on the scene as if shadowing the Jackson 5’s every move, quickly becoming regarded as their chief rivals. This mixed-gender family group expanded to a nine-member lineup for the release of “Boogie Fever” (from Showcase) and “Hot Line,” both signature songs crafted by Freddie Perren, one of the architects behind the Jackson 5’s classic material. Foster Sylvers, who released a solo album at age eleven, would later be tapped to work on Janet Jackson’s debut.

Meanwhile, DeBarge stepped into the void left when the Jackson 5 departed Motown. Their predecessor group Switch had entered Motown through Jermaine Jackson’s introduction, and James DeBarge became Janet Jackson’s first husband, creating numerous points of contact between the two families. Specializing in sentimental falsetto-laden expression, the group produced enduring works including “I Like It” and “All This Love” (from All This Love).

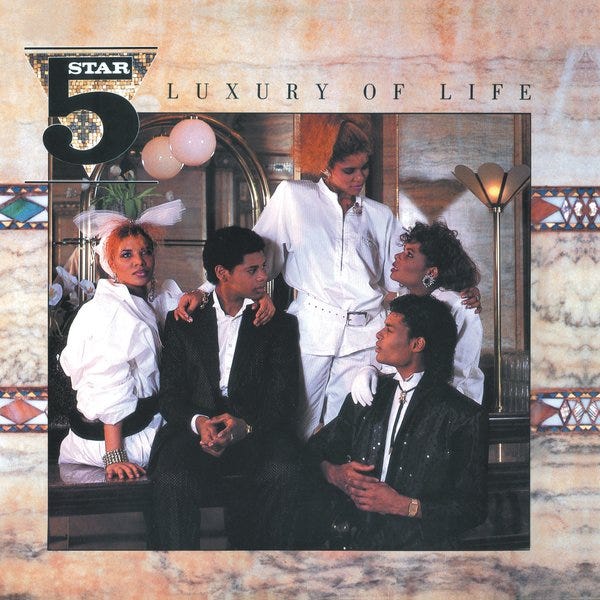

Five Star burst out of the UK as a Pearson family unit led by female vocalists, their sound carrying the fresh 1980s beats that also characterized late-period DeBarge. Though often dismissed as pop-oriented, their debut Luxury of Life, produced by Philadelphia’s Nick Martinelli, and Rock the World, which featured production contributions from Sylvers sibling Leon and paralleled Michael’s Bad-era work, deserve attention within this framework.

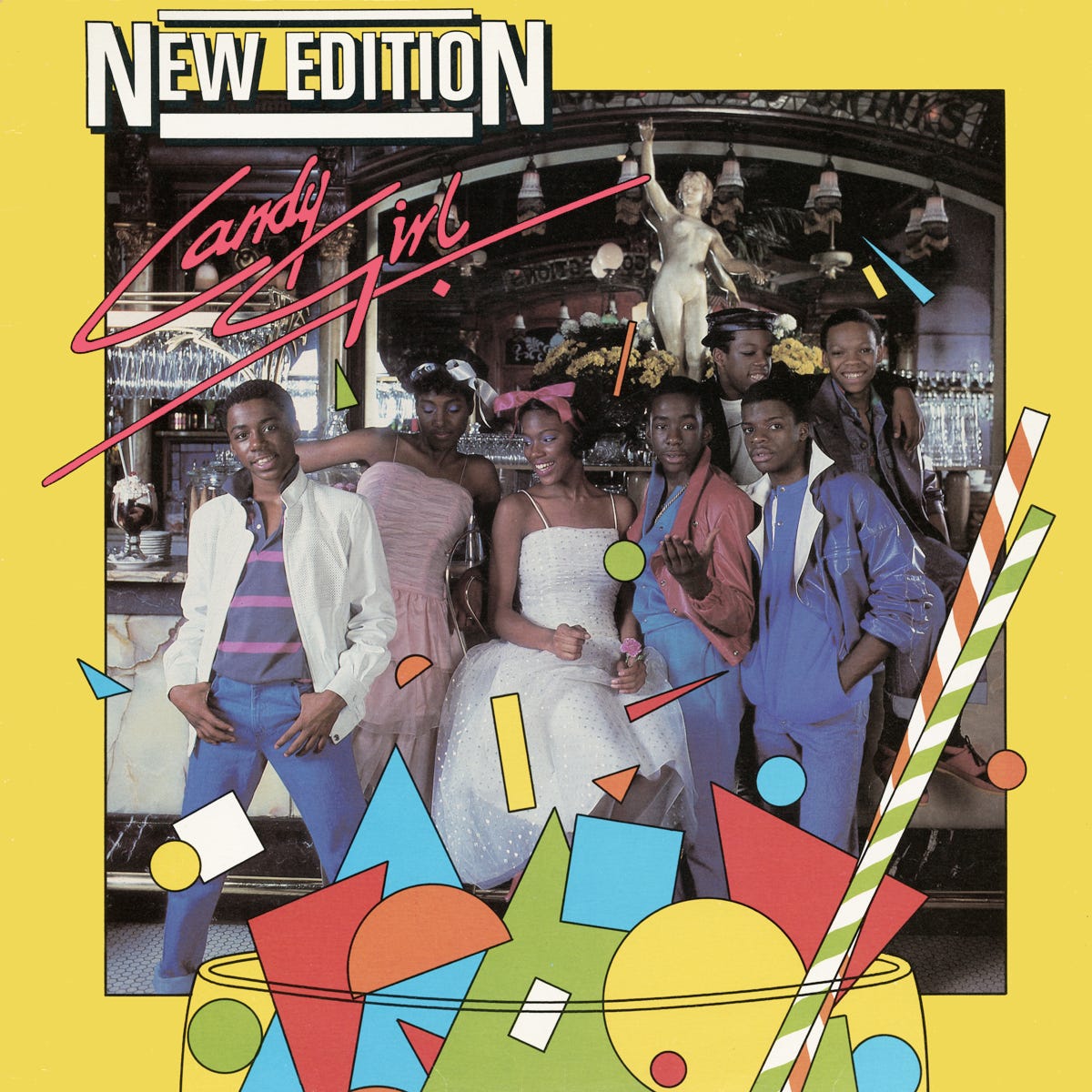

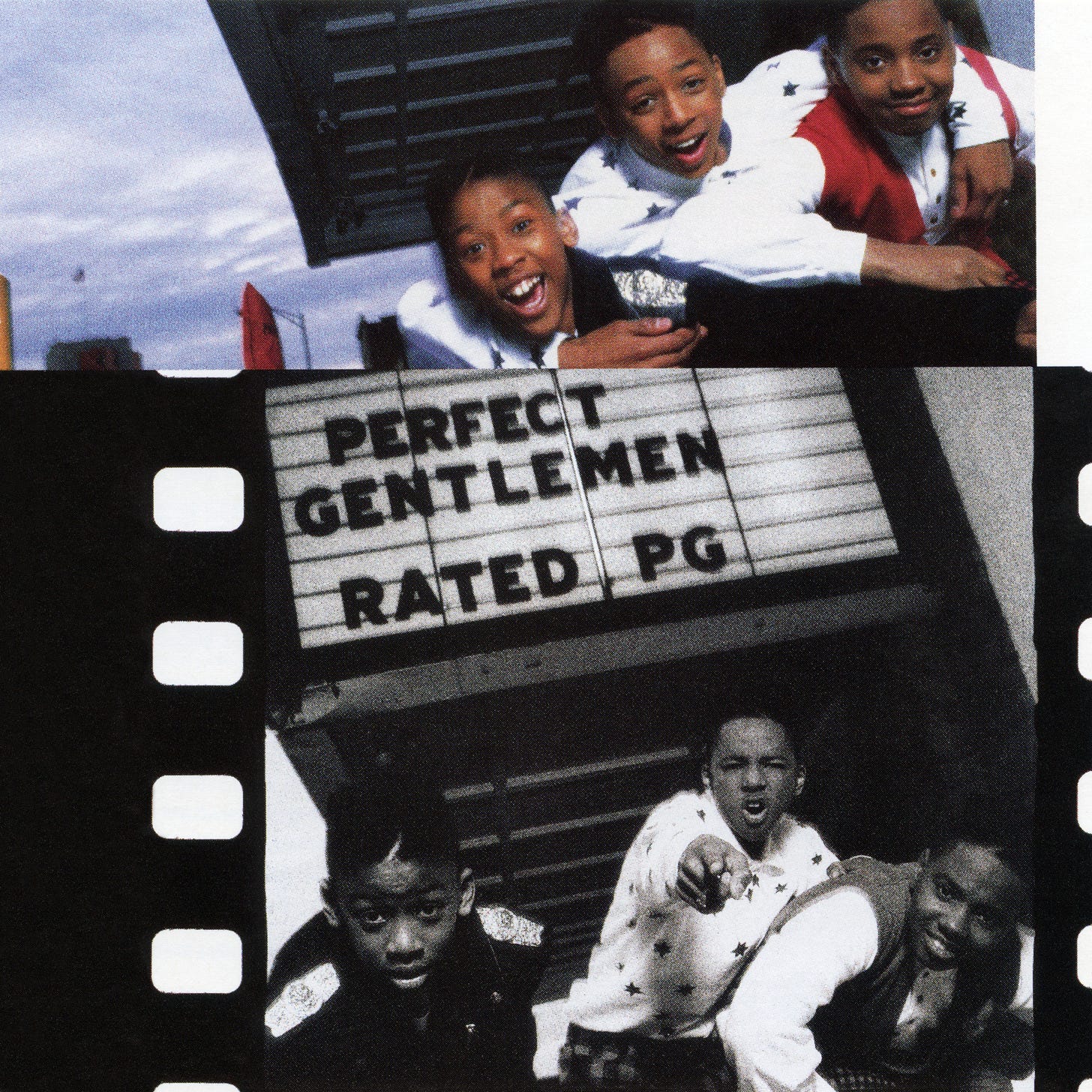

Though not blood relatives, New Edition pursued the Jackson 5 legacy most directly, breaking through with the title track from Candy Girl. In their early years, they truly inherited the mantle of Michael’s Motown-era group. Maurice Starr, who launched them, continued deploying the same bittersweet formula into the 1990s with Perfect Gentlemen’s Rated PG. Starr also guided New Kids on the Block, Homework, Classic Example, and the Superiors.

New Edition’s Michael Bivins later devoted himself to discovering new talent, and the group he unearthed, Another Bad Creation, released Coolin’ at the Playground Ya Know!, which covered New Edition’s “Jealous Girl” while otherwise embracing the Dallas Austin-produced new jack sound that dominated the early nineties.

The Boys, also from the new jack generation and a genuine sibling group, debuted on Motown. Their L.A. Reid and Babyface-produced “Dial My Heart” (from Messages from the Boys) stands as a pinnacle. Hi-Five’s Hi-Five, featuring Teddy Riley’s production on “I Like the Way (The Kissing Game),” cannot be dismissed as mere kids’ fare. And Troop’s Attitude absolutely demands inclusion, containing the masterpiece “Spread My Wings,” produced by Chuckii Booker and showcasing lead vocalist Steve Russell, who had built a local reputation since childhood performing Michael Jackson material.

Notably, Chuckii Booker served for a time as bandleader for Janet Jackson’s tours.

The Sylvers, Showcase

James Jamerson’s bass line opens “Boogie Fever” with a figure lifted straight from the Beatles’ “Day Tripper,” and the graft tells you everything about where this album sits. Freddie Perren had just left Motown, where he’d written the Jackson 5 into history. Capitol handed him nine siblings from Watts and told him to do it again. Edmund Sylvers handles lead duties with a tenor that splits the difference between maturity and youth. He’s nineteen, old enough to sell desire, young enough to project innocence. Foster, the eleven-year-old whose voice punctuates the bridge with yelping ad-libs, provides the connection to Michael’s falsetto acrobatics. When all nine voices stack into harmony on the chorus, the Sylvers become their own choir, too large for any single comparison.

Beyond the hits, Showcase wanders through arrangements that Wade Marcus built for maximum versatility. “Free Style” lets the rhythm section stretch into proto-funk territory, while ballads like “Cotton Candy” pursue the sweet soul of the early seventies. The production never quite commits to a single identity, which may explain why the Sylvers peaked here and descended rapidly after. What the album captures is Perren testing whether his formula could travel. The answer proved complicated. “Boogie Fever” topped both the pop and R&B charts in 1976, vindicating the approach. But the Sylvers never launched a Michael, never produced a solo star who could transcend the group’s machinery. They remained, finally, a collective. Edmund died at forty-seven. Foster faded from public view. The siblings scattered. But for one album, Perren’s theorem held. Enough voices singing together could approximate magic. — B.O.

DeBarge, All This Love

El DeBarge wrote the title track, hoping Marvin Gaye would record it. Gaye had already left Motown by the time the song was finished, so the twenty-one-year-old kept it for himself. His vocal on “All This Love” channels Gaye’s multi-tracked intimacy from the I Want You sessions, harmonizing with his own overdubs until the distinction between singer and chorus dissolves. Another Motown prodigy claiming his inheritance. The DeBarge siblings arrived at Gordy Records through their older brothers in Switch, a group Jermaine Jackson had ushered onto the label. Family connections webbed through everything. James DeBarge, who plays keyboards throughout, would marry Janet Jackson the following year. Iris Gordy, Berry’s niece, co-produced. The album sounds like what it was: a house project, talent groomed within Motown’s remaining infrastructure.

“I Like It” opens with synthesizer stabs and a groove indebted to the boogie sound then dominating Black radio. El’s countertenor floats above the arrangement, neither pleading nor demanding, simply present. The lyric offers nothing beyond attraction stated plainly. That simplicity proved commercial. The single climbed to number two on the R&B charts and announced that DeBarge could compete with the flashier acts of the moment. Bunny DeBarge takes lead on “It’s Getting Stronger,” her voice huskier than her brother’s, more rooted in the body. The sibling interplay across the album—Mark’s contributions, Randy’s arrangements—creates texture without showcasing any individual beyond El.

What distinguishes All This Love from its competition is the songwriting’s emotional intelligence. These are songs about recognizing love, about the moment when feeling clarifies into commitment. “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again” narrates romantic caution dissolving. The vulnerability reads as genuine because El sounds genuinely vulnerable, his falsetto trembling at the edges of notes. Motown had spent two decades teaching singers to project confidence. DeBarge hinted that uncertainty could seduce just as effectively. — P

Five Star, Luxury of Life

The Pearson siblings arrived from the UK with choreography tight enough to rival any American competitor and production values borrowed from Philadelphia. Nick Martinelli handled five tracks, including the singles that charted, bringing the same sleek professionalism he’d applied to Loose Ends. The result sounds expensive, cosmopolitan, determined to prove that British R&B could match its transatlantic models. Deniece Pearson carries the lead vocals with a soprano that favors precision over grit. Her siblings—Delroy, Doris, Lorraine, and Stedman—fill harmony parts and share occasional verses, but the family dynamic reads as more corporate than intimate. Their father Buster managed everything. The packaging positioned them as wholesome, aspirational, safe for teenage bedrooms across Europe. Luxury of Life exposes the distance between craft and soul. The Pearsons could dance, could harmonize, could project professionalism. Whether they could move a listener remained uncertain. The album spent seventy weeks on the UK charts without ever approaching transcendence. Five Star occupied a middle zone, which is too polished for cult appeal, too British for American dominance, too calculated for genuine devotion. They made music for people who wanted the Jackson 5 experience without the Jackson 5’s danger. — P

New Edition, Candy Girl

Maurice Starr spotted them at a Boston talent show and signed them for five hundred dollars and a Betamax player. The five boys from Roxbury’s Orchard Park Projects ranged from thirteen to fifteen. Ralph Tresvant handled most leads with a tenor that recalled young Michael’s without quite matching it. Bobby Brown anchored the low end and radiated charisma beyond his years. Starr heard money. The title track, written and produced by Starr with Arthur Baker, knocked George Clinton’s “Atomic Dog” off the top of the R&B chart in May 1983. The song works as pure bubblegum, a narrator comparing his girlfriend to confectionery, the metaphor so simple it barely registers as metaphor. What sells it is Tresvant’s delivery, earnest without irony, and the Jackson 5 ghost haunting every vocal arrangement. Starr had studied the Corporation’s playbook and reproduced its findings.

The fear expressed—romantic loss, abandonment—sounds precocious from fifteen-year-olds, but precocity was the point. New Edition performed adulthood before they’d lived it, which was exactly what their audience wanted. Rehearsal without risk. The production carries Arthur Baker’s fingerprints: Linn drums, vocoder effects, and electronic textures that connect to the electro-funk then dominating New York. The boys could actually sing, actually harmonize, actually work as a unit. Their tragedy was contractual. Streetwise’s accounting practices meant they never saw royalties proportional to their success. The lawsuit that followed launched them toward MCA and genuine stardom. Candy Girl documents a childhood exchanged for fame, innocence packaged and sold. That Starr would repeat the formula with New Kids on the Block proves the template’s durability. That New Edition escaped to build actual careers proves their talent exceeded their circumstances. The album remains a time capsule of early-eighties teen marketing, a document of Black Boston’s brief moment in the pop spotlight, and a reminder that exploitation and artistry often share the same studio. — B.O.

Perfect Gentlemen, Rated PG

Maurice Starr’s son headlines the group, which tells you most of what you need to know. Starr assembled Perfect Gentlemen from Boston teenagers after his success with New Edition and New Kids on the Block, applying the same methodology: young voices, tight choreography, wholesome imagery. The boys range from eleven to thirteen. The title puns on their rating and their name. Nothing here escapes calculation. “Ooh La La (I Can’t Get Over You)” peaked at number ten on the Hot 100, validating Starr’s instincts for the third consecutive decade. The song floats on a synthesizer bed typical of late-eighties pop-R&B, the hook memorable if not original, the vocals competent if not distinctive. Corey Blakely, Maurice Starr Jr., and Tyrone Sutton trade lines without any single voice claiming authority. The production ensures they blend into product.

What Rated PG lacks is necessity. New Edition had arrived when their sound was new, when the Jackson 5 model hadn’t yet calcified into formula. Perfect Gentlemen arrived after the formula had produced multiple iterations, when audiences could recognize the machinery even while enjoying its output. The boys sing about crushes, promise eternal devotion, perform the emotions their demographic was assumed to want. Nothing surprises. The album disappeared quickly. Perfect Gentlemen reformed briefly, added members, recorded a second album on Warner Bros. that attracted less attention. Starr’s formula had finally reached its expiration date. What remains is a document of diminishing returns, proof that even reliable templates eventually bore their audiences. The boys were talented enough. Their material wasn’t. In pop music, that mismatch typically resolves in one direction. — P

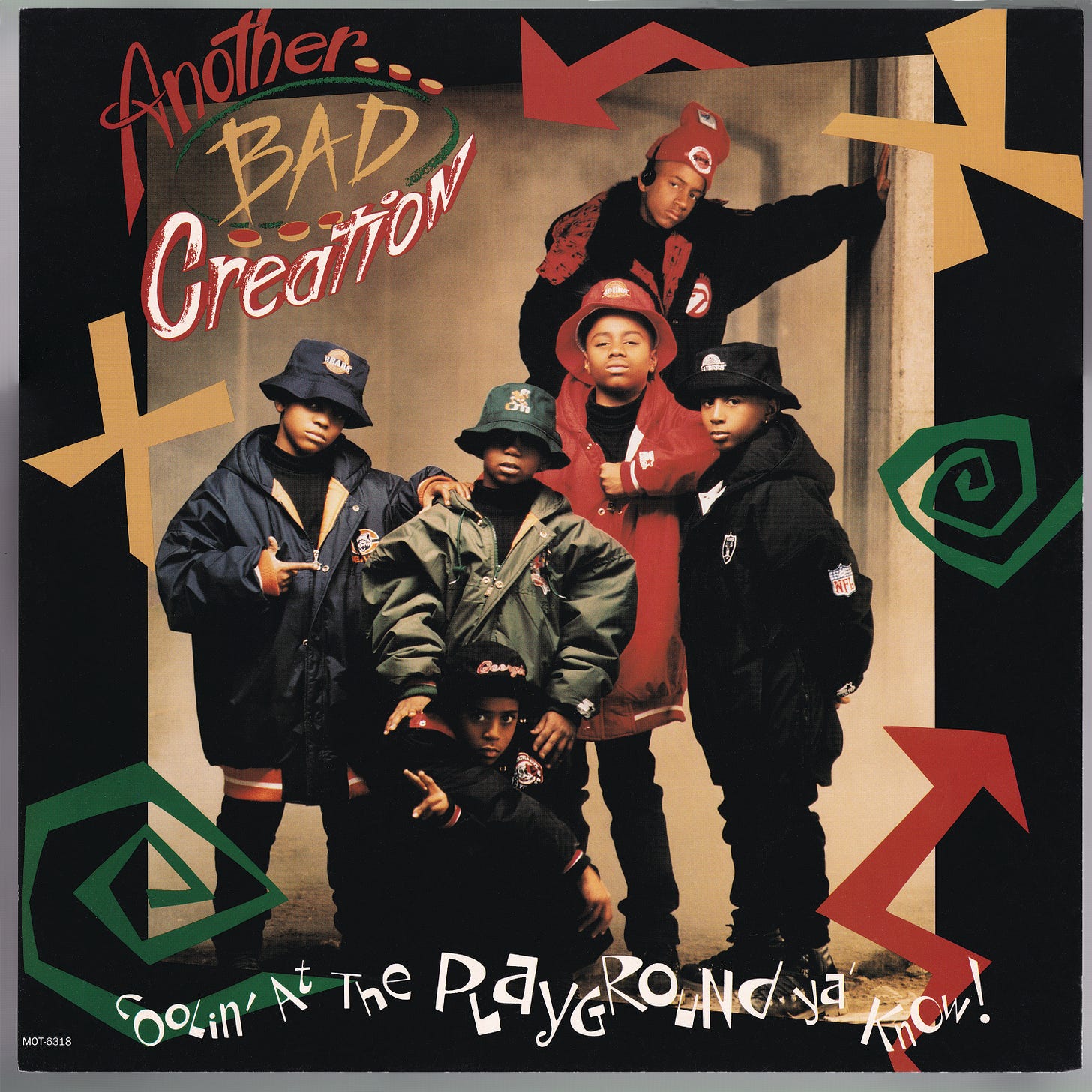

Another Bad Creation, Coolin’ at the Playground Ya Know!

Michael Bivins discovered them in Atlanta and brought Dallas Austin to produce. The Bell Biv DeVoe member had learned from his own career that teen groups required adult supervision, that hit records grew from professional collaboration rather than youthful enthusiasm alone. Another Bad Creation—five boys aged ten to thirteen—supplied the faces and voices. Austin supplied the beats. “Iesha” introduced the group through a love letter so earnest it almost transcends its calculation. The narrator addresses his crush by name, confessing devotion over a new jack swing groove that Austin constructs from programmed drums and funk samples. Bivins himself appears in the video and on the track, lending credibility by association. The single reached the top ten, and the album went platinum within months of release.

The cover of New Edition’s “Jealous Girl” pays tribute to Bivins’s roots while exposing the young singers’ limitations. They can approximate the original’s harmonies without matching its emotional intelligence. Austin’s production compensates, layering enough sonic activity to distract from vocal weaknesses. The strategy works often enough. “Playground” became another top ten hit, its celebration of childhood recreation resonating with the demographic who actually inhabited playgrounds.“Spydermann,” produced by Dr. Freeze and Howie Tee, adds hip-hop elements that Austin’s tracks mostly avoid. The misspelling dodges trademark issues while the song itself lets the boys flex rhythmically, trading bars in a style that anticipated later kid rap acts.

Austin blends new jack swing’s rhythmic sophistication with bubblegum’s emotional simplicity, creating a hybrid that sounds contemporary without alienating protective parents. The boys wear Starter jackets and oversized jeans, telegraphing street credibility while remaining thoroughly unthreatening. Motown, which had struggled through the eighties, briefly reclaimed cultural relevance through these Atlanta children. The formula worked until it didn’t. Another Bad Creation’s second album didn’t do well, and the group dissolved into the decade’s forgotten footnotes. — B.O.

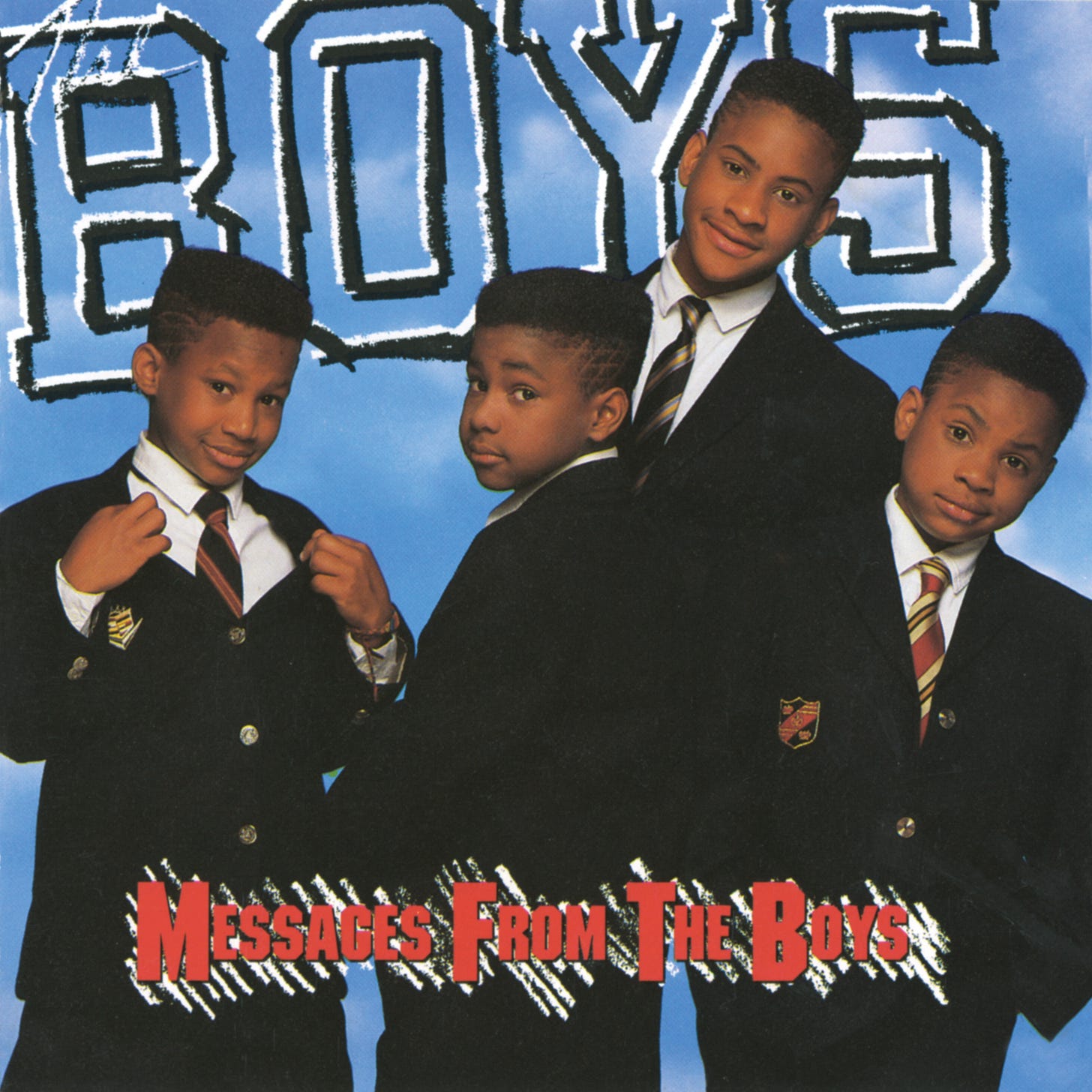

The Boys, Messages from the Boys

L.A. Reid and Babyface walked into the Abdulsamad family’s home and performed “Dial My Heart” live, convincing the four brothers that these producers understood their potential. The song became the album’s cornerstone, its opening synth figure and locked groove establishing a template that would dominate late-eighties R&B. Khiry, Tajh, Hakim, and Bilal ranged from nine to sixteen. They sang like they’d been training since birth, which they essentially had. “Dial My Heart” topped the R&B chart in late 1988, its message—calling a girl repeatedly, waiting for connection—translated into synthesizer pulses and drum machine patterns that sounded simultaneously mechanical and warm. The brothers’ harmonies arrive precisely on cue, voices blending without any single personality overwhelming the others. Reid and Babyface understood that teen groups worked best as collectives, individual distinction subordinated to group identity. “Lucky Charm” duplicated the formula, reaching number one the following spring.

Beyond the Reid/Babyface tracks, Messages from the Boys includes material the brothers wrote and produced themselves. “Be My Girl” lets them stretch toward the Prince-influenced funk that their age made impossible to fully inhabit. The ambition exceeds the execution, but the attempt reveals artists who conceived of themselves as more than product. The Abdulsamad brothers later renamed themselves Suns of Light and moved to Gambia, abandoning American pop for West African recording studios. That trajectory, from Motown teen idols to expatriate artists, distinguishes them from their peers. Most boy band alumni fade into nostalgia circuits or reality television. The Boys genuinely departed, transforming themselves beyond recognition. Messages from the Boys captures them before that transformation, talented kids navigating an industry that prized youth above all else, making music that exceeded their handlers’ expectations. — B.O.

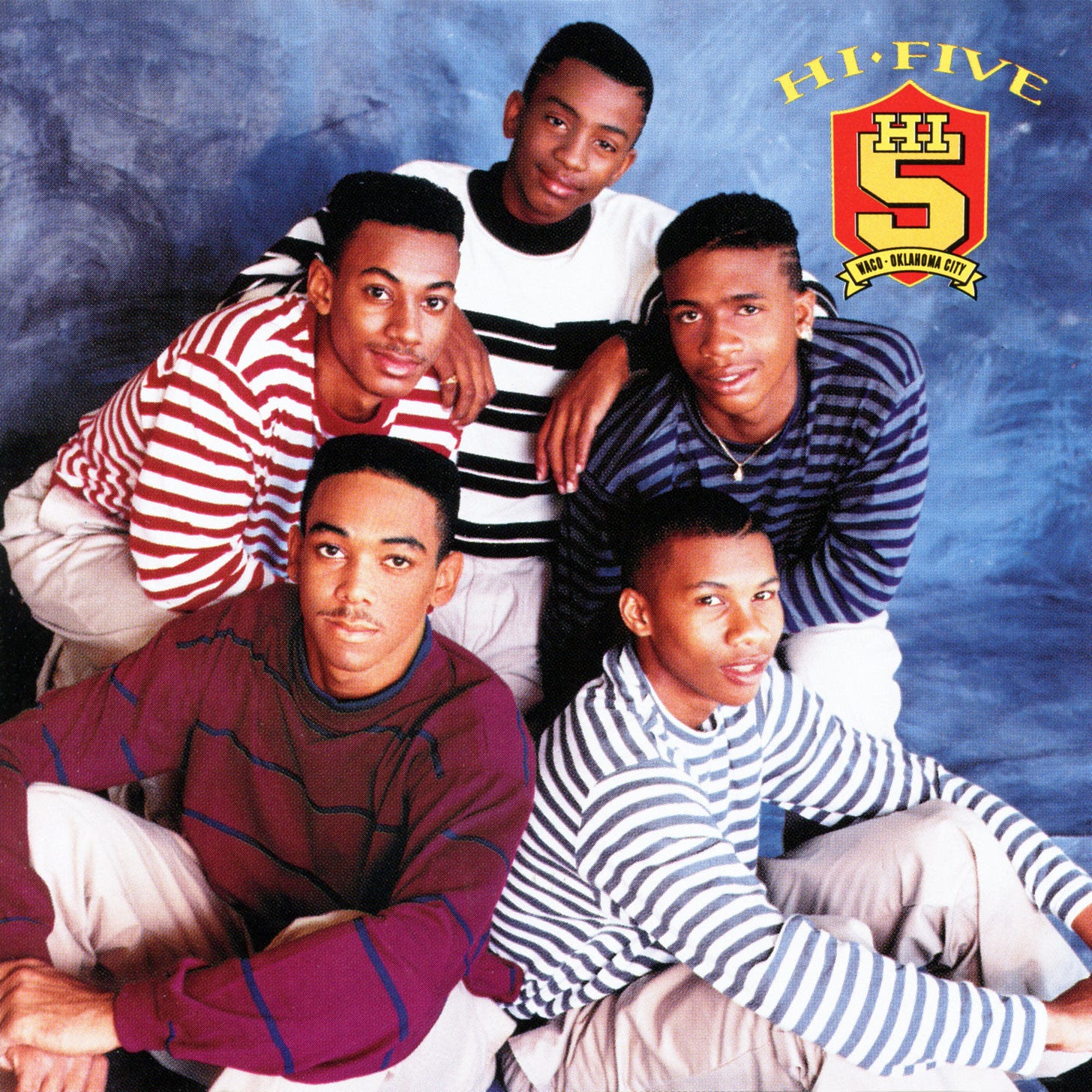

Hi-Five, Hi-Five

Teddy Riley produced the bulk of this debut, which meant the Waco teenagers arrived already sounding like the future. New jack swing’s architect gave them grooves that bounced harder than any teen group had ridden before, drum patterns that owed more to hip-hop than to Motown, synthesizer textures that crackled with contemporary energy. Tony Thompson’s lead vocals anchored the sound, his tenor flexible enough to handle both romantic pleading and rhythmic precision. “I Like the Way (The Kissing Game)” was EVERYWHERE in early 1991, its hook so insistent it penetrated radio rotations for months. Bernard Belle and Dave Way co-wrote with Riley, constructing a lyric that celebrates physical affection without quite crossing into adult territory. The boys sing about kissing as if it were achievement enough, and for their audience it probably was. The production frames their voices within layered percussion and synth stabs that sound aggressive and tender simultaneously.

“I Can’t Wait Another Minute” was almost just as big as the previous single. Thompson’s vocal runs display technical facility beyond his years, while the other members—Roderick Clark, Marcus Sanders, Russell Neal, Toriano Easley—fill harmony parts with professional competence. Easley’s presence proves temporary; he was removed from the group before the album’s release after being charged with murder. Treston Irby lip-syncs his parts in subsequent videos. The connection to Mobb Deep is genuine if surprising. Prodigy, who would become half of the legendary rap duo, appears as a fifteen-year-old on “Merry-Go-Round.” His presence links Hi-Five to a harder New York lineage, complicating the group’s wholesome image. Riley’s production elevates what might otherwise have been standard teen fare. The drums hit with genuine force. The bass lines move with hip-hop’s syncopation. Hi-Five sounds like a group that could survive beyond their immediate moment, though tragedy and bad luck would prevent that survival. Thompson died in 2007. Clark was paralyzed in a 1992 car accident. The album remains, polished and energetic, a document of Riley’s peak powers applied to unlikely subjects. — B.O.

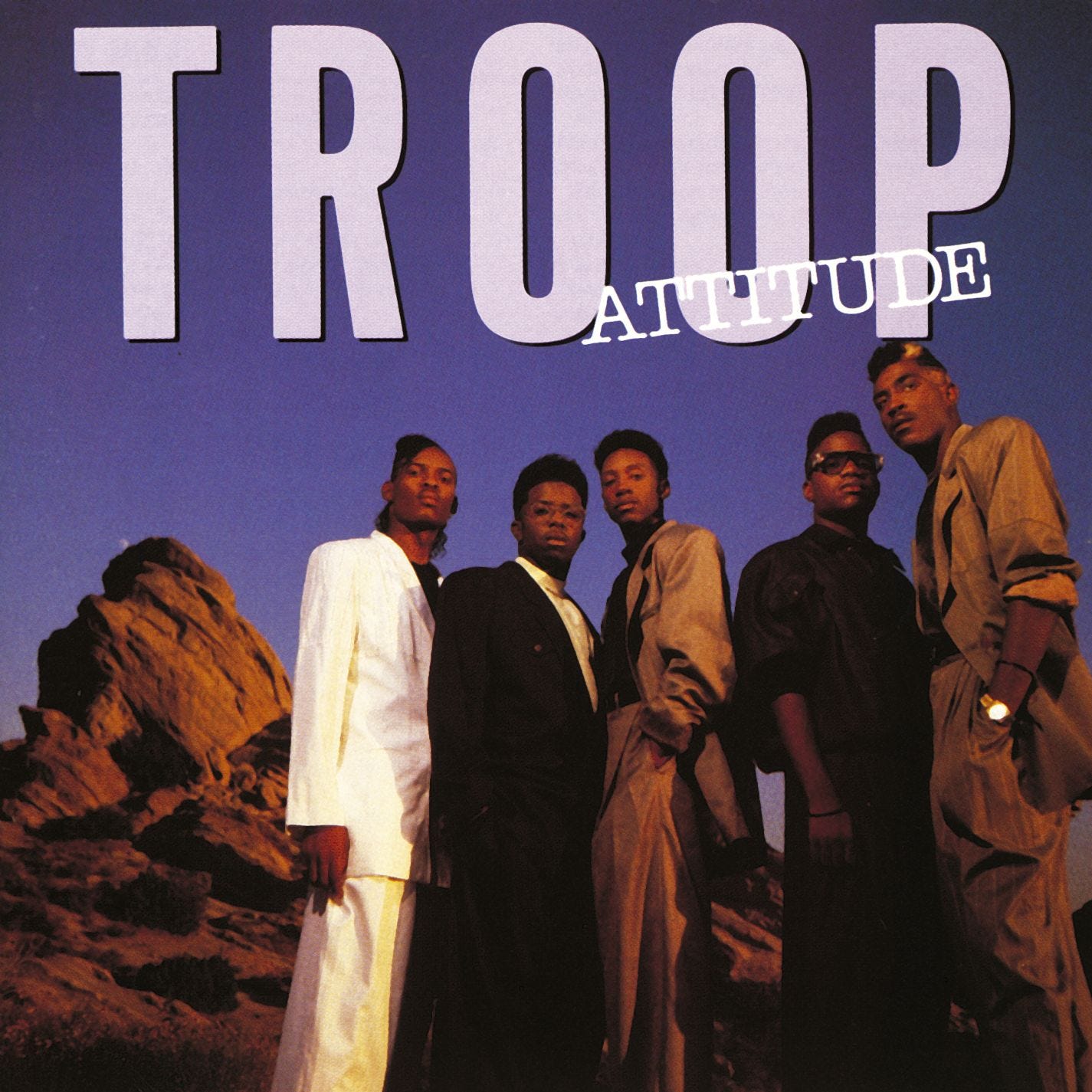

Troop, Attitude

Chuckii Booker wrote and produced “Spread My Wings,” and Steve Russell’s vocal on the song remains one of new jack swing’s purest performances. Russell had spent his childhood in Pasadena imitating Michael Jackson at Venice Beach, drawing crowds with his dancing and singing. That training surfaces in every phrase, the way he stretches syllables, the way he drops into falsetto at emotional peaks. The comparison to Michael is inevitable and, for once, warranted. The five members of Troop—Russell, Allen McNeil, John Harreld, Rodney Benford, and Reggie Warren—met as children and won a Puttin’ on the Hits contest by lip-syncing to New Edition’s “Cool It Now.” Their debut album produced “Mamacita,” which LeVert produced to number two R&B. Attitude followed with higher ambitions and stronger material.

Booker’s other contribution, a cover of the Jackson 5’s “All I Do Is Think of You,” also reached number one. The original appeared on the Jacksons’ 1975 album Moving Violation, a forgotten track until Troop resurrected it. Their version strips the arrangement to its emotional core, Russell’s voice carrying the melody with devotion that sounds personal rather than performed. He sings about obsessive love as if he’s lived it. Dallas Austin makes his production debut on “My Music” and “I Will Always Love You,” working with his mentor Joyce Irby. The tracks point toward the sound Austin would soon perfect with TLC and Boyz II Men. Gerald Levert handles “That’s My Attitude” and “For You,” with a young Trent Reznor credited among the recording engineers. The future Nine Inch Nails architect appears as a footnote to New Jack Swing’s rise.

What distinguishes Attitude from its competitors is the consistency of vocal performance. They were young men who could genuinely sing, who had developed their craft through years of local performance. Russell’s subsequent career as a songwriter—penning hits for Chris Brown, Jordin Sparks, Jennifer Hudson—confirms the talent that surfaces throughout this album. Attitude went platinum and produced two number-one singles, yet Troop remains underrated relative to their peers. The music argues for reconsideration. — P