The Lineage of Black Messiah

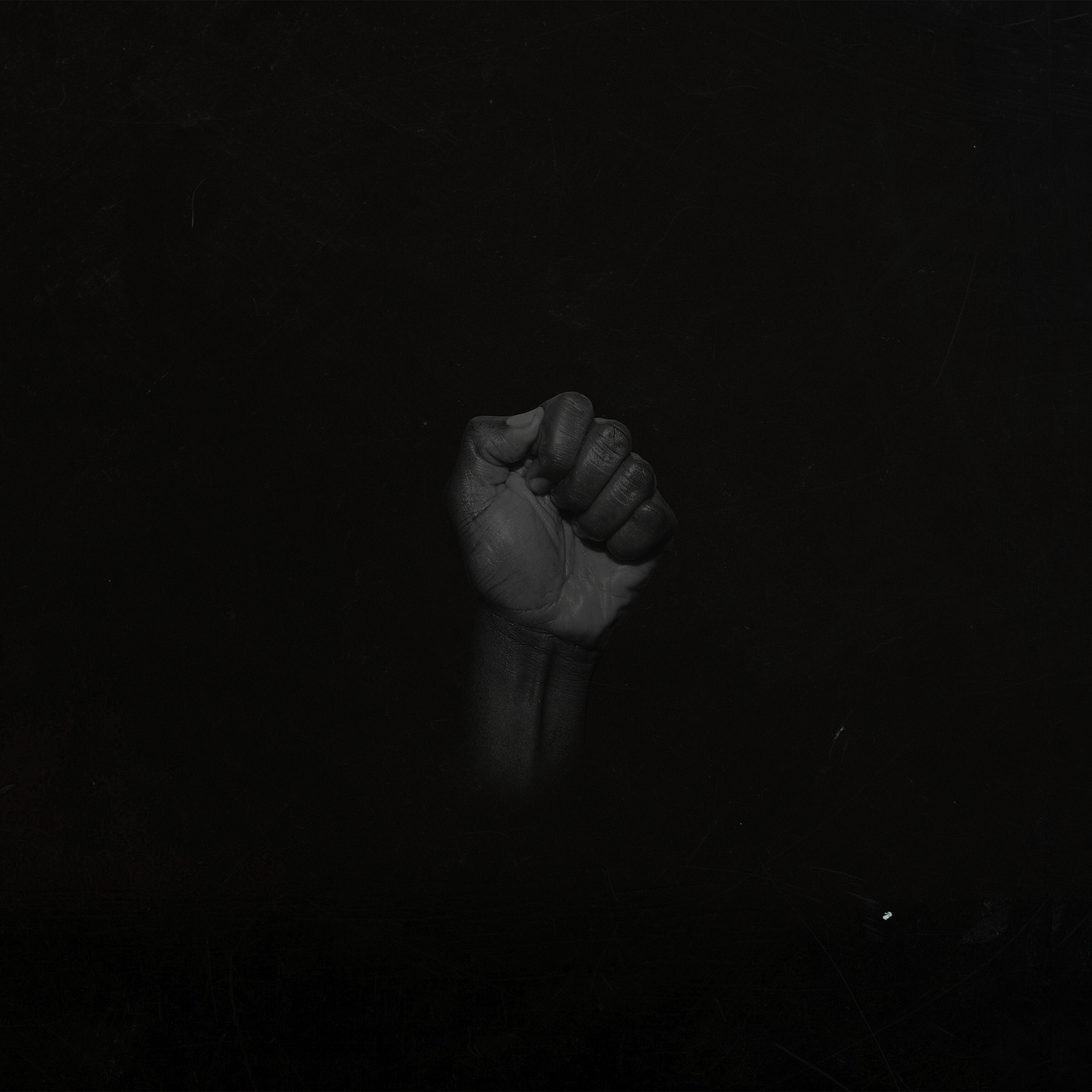

We are still in that orbit. And so the lineage is not a freighted tomb but a living relay. The fire stoked in 2014 continues to burn, shifting shape, illuminating new angles.

The winter of 2014 was brittle with tension. Ferguson had burnt through late summer; protests in New York and Baltimore cast long shadows; Black Lives Matter slogans haunted every march, hashtag, and newsroom. The legacy of the civil‑rights era had become a weight pressing on a generation that felt it was being reborn through ash and sirens. In that climate, D’Angelo’s Black Messiah arrived not as a comeback but as a signal, like an old lighthouse suddenly beaming again at sea: necessary, urgent, unignorable.

When Black Messiah dropped on December 15, 2014, it landed in the world already primed for vertigo. The streets were restless; the Internet was in constant revolt. And here was D’Angelo, after fourteen years away, releasing an analog, analog‑rich funk‑soul record with no lead singles, no viral preamble, minimal press, no trailer. It was a throwback tactic in a forward moment. The title, Black Messiah, felt heavy with paradox: was he assuming the mantle of a savior, or calling on many saviors? As many understood, the name was meant to be communal: we are the messiahs.

From its opening refrains onward, the record confronted time itself. The grooves stutter, stretch, drag, and lurch. On “Prayer,” the drums and bass run into each other in disorientation, only to lock in with uncanny precision. The vocal lines twist ahead of the pulse, then sag behind it, hurling you out of time and dragging you back in. It is music that negotiates tension between rupture and reconciliation. And it is a political record, not just by subject but by structure: it demands that the listener renegotiate their relation to rhythm, to economy, to legacy.

But the rebirth was not solo. The Vanguard—Questlove, Pino Palladino, Isaiah Sharkey, Cleo “Pookie” Sample, Roy Hargrove (posthumously), and Kendra Foster—were co‑custodians of the album’s DNA. Palladino, in particular, had long been D’Angelo’s anchor: his fretless voice able to catch the drift of chaos and center it. Producer Russell Elevado likewise held space for “imperfection” in analog warmth, engineering the record so it feels alive, breathing through its cracks. The Vanguard’s chemistry was the proof: they didn’t simulate a past era, they dragged its ghost into the present and insisted it still breathed.

In that sense, Black Messiah didn’t just revive D’Angelo—it tuned a new reference frequency for Black music’s sense of time, groove, and purpose. It enchanted a lineage forward.

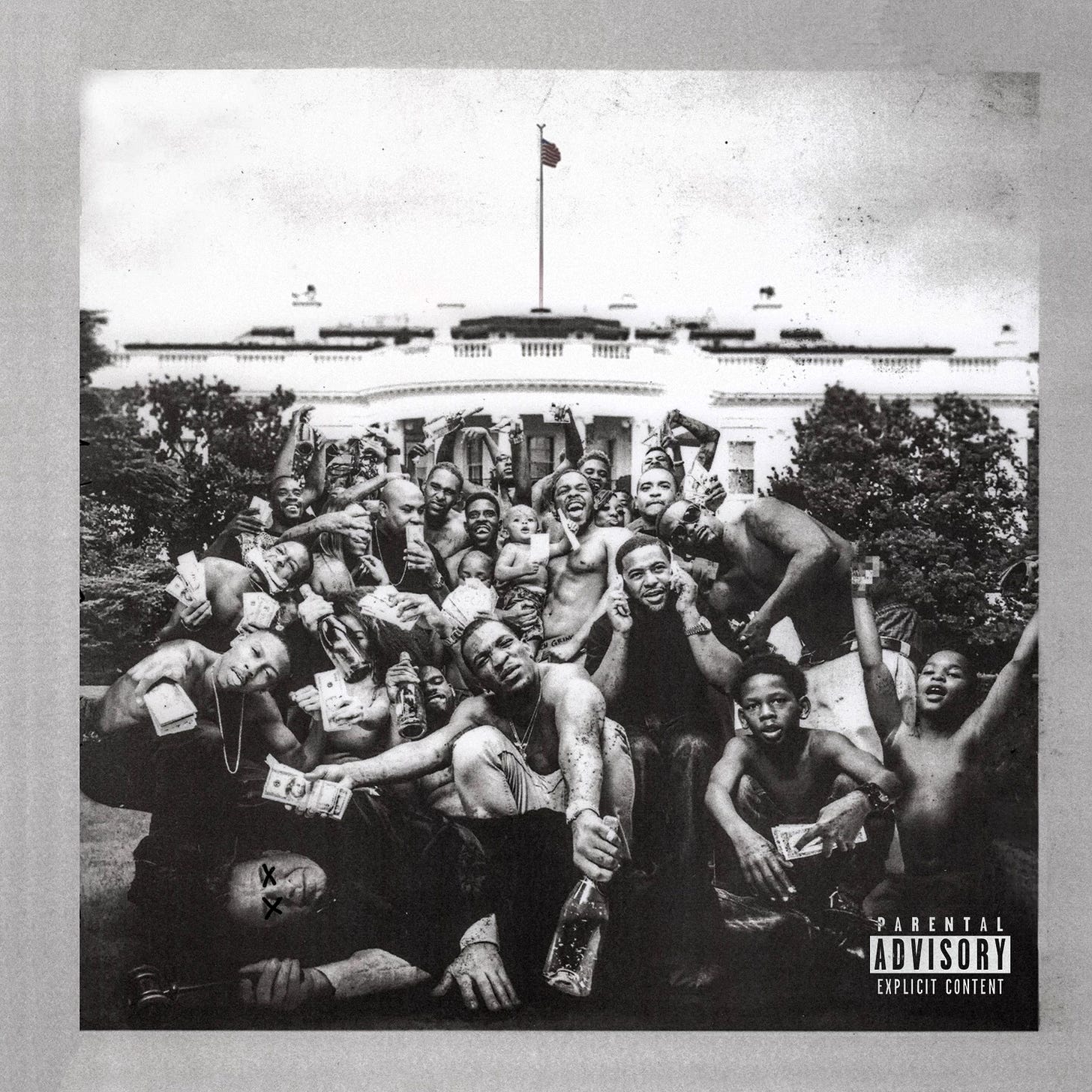

Kendrick Lamar, To Pimp a Butterfly

Kendrick Lamar staged a summoning over various mixes of jazz and funk. When To Pimp a Butterfly unexpectedly from the release date, it sounded like America was cracking open—an urgent fissure in sound, politics, and memory. What Black Messiah had already opened (a portal back through live instrumentation, fractured groove, analog grit), Butterfly stepped through with both caution and defiance. Under the helm of Terrace Martin and Thundercat, Kendrick invited a band into the chassis—not as ornament, but as co‑narrators. According to Terrace Martin, the D’Angelo record influenced their palette, pushing them to rent vintage keyboards and re-sensitize ears to harmonic complexity and looseness. In “Wesley’s Theory,” Kendrick summons George Clinton, nods to funk futurism, lets horns scratch dissonance into the beat, and lets bass push against the meter: those are Black Messiah moves. His drift through “For Free?” or “Mortal Man”—where the beat recedes and the voice confronts itself—is a cousin of D’Angelo’s own voice‑as-prophet posture. Butterfly inherits Black Messiah’s refusal of tight grid stability; it extends the possibility that Black music can resist quantization—not just in sound but in political time. Butterfly reaffirms that groove carries memory, that pressure is relational, and that to speak for your people is to do so within a contested pocket of time.

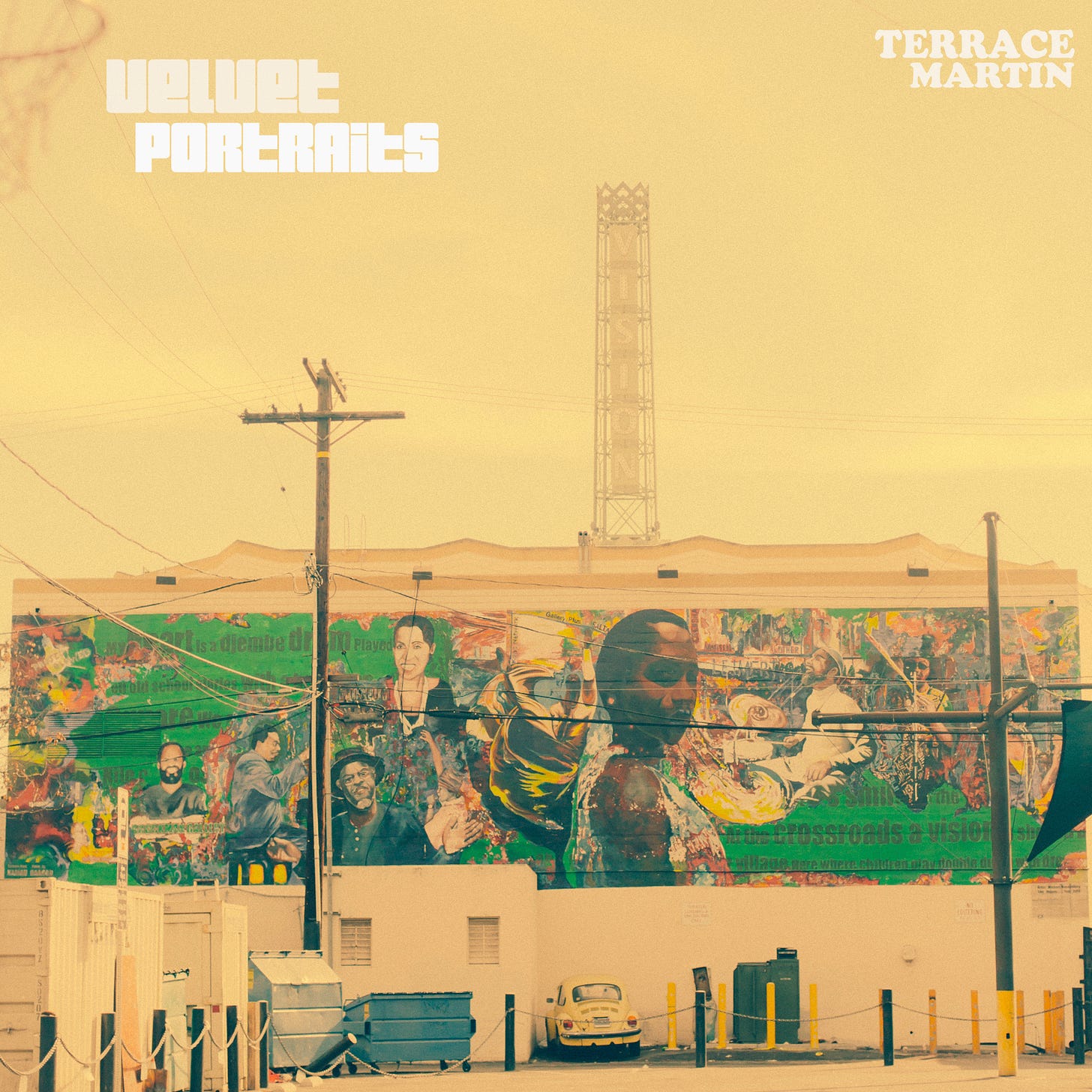

Terrace Martin, Velvet Portraits

As someone already embedded in the Black Messiah sessions and lineage, Velvet Portraits moves in shades, like jazz voice tones shifting, like dusk sliding into night. That interior posture is one of the key debts Velvet Portraits owes to Black Messiah. The latter revived an intimate, human scale: grooves that breathe, notes that sag, silence as architecture. Terrace Martin, who had been intertwined with that record’s session ecosystem, filters Black Messiah through jazz sensibility. In Velvet Portraits, you hear chordal voicings that avoid full resolution, horn lines that kiss the edges of the bar, and rhythms that push without pushing too hard. Because Terrace Martin was both an inheritor and collaborator in that post‑Black Messiah field, his album feels self‑reflexive: he is taking the rupture that Black Messiah instigated and refracting it inward. It is not a copy but a conversation in microtiming, in layering, in the space around horn entries, in the pulse behind a sax flourish. Velvet Portraits is, in its restraint, a demonstration of how Black Messiah’s looseness can be disciplined, how a lineage of groove can live in delicate interiors—not just in big stage funk statements.

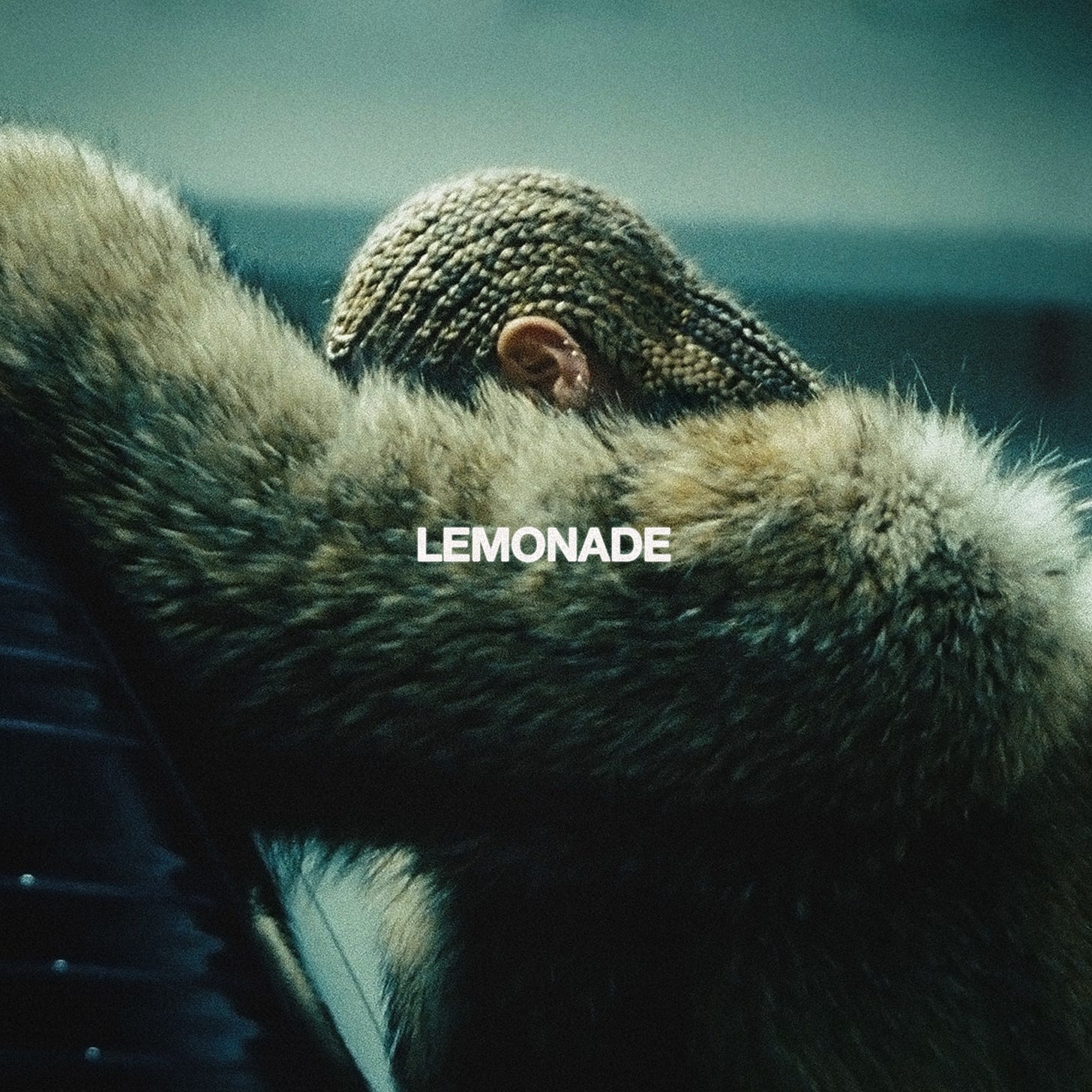

Beyoncé, Lemonade

Beyoncé doesn’t walk into Lemonade—she surfaces, as though through water, with a voice that’s already laden. The opening tracks (“Pray You Catch Me,” “Hold Up”) unspool in a kind of slow reveal: the pulse is felt under the skin, not always heard at first. You listen for the drums; they drift in, almost like heat haze. That method—arriving through tension, letting the groove materialize rather than announcing itself—is one of the clearest fingerprints of Black Messiah on Lemonade. D’Angelo taught us that arrival needn’t be loud.

Across Lemonade, Beyoncé fractures genre—rock, gospel, trap bounce, blues, soul—precisely because Black Messiah had reopened the possibility of such pluralism within a single frame. But more than genre, she inherits Black Messiah’s elasticity in time. In Lemonade, beats drip, rhythmic cadences double back, and the transitions feel like memory more than construction. On “Freedom,” the drum resist, the voices rise in registers that threaten rupture—but they resolve in a communal cry. D’Angelo’s work taught that in the slippages between stability and disintegration, there is creation. Beyoncé captures that: she holds shame, healing, revolt, eroticism—all in sonic tension.

And in its politics, Lemonade embodies Black Messiah’s doctrine that sensuality and protest are not separable. Its visual narrative overlays motherhood, betrayal, Black femininity, and ancestral pain. When she sings “I destroy you with the truth,” she’s demanding reckoning, through voice, through rhythm, through imagery. That insistence echoes Black Messiah’s internal theology: the groove is sacrament, the vulnerability is weapon, the community is terrain. Lemonade speaks back to Black Messiah not as a follower but as an interlocutor, taking its template, stretching its coat, and turning it into armor.

Jordan Rakei, Cloak

Jordan Rakei appears not by reclaiming a groove but by resurrecting a tension. His music seems to arrive as though it had always been there, submerged. In the quiet undercurrent of Cloak, you find influences of Black Messiah’s destabilization of time: piano chords that hang in space, kick drums that push forward then stall, vocals that hover just off the beat before aligning. Black Messiah reopened for listeners the possibility that groove can be porous—that rhythms can blur between propulsion and suspension. In Cloak, tracks such as “Midnight Mischief” and “Talk to Me” enact that possibility. Rakei’s voice, “quietly insistent,” luxuriates within the groove even as it resists it. The production carries jittery hi-hats and drum programming that recalls J Dilla’s “boom-clap” feel—electronics bent to human imperfection, a territory D’Angelo occupied. In this way, Cloak doesn’t imitate Black Messiah; it reorients it toward a younger vulnerability, translating its groove logic into a hushed, spectral palette.

Blood Orange, Freetown Sound

Dev Hynes had always existed between worlds—Black Britishness and American dislocation, fluid identities, and diasporic anxieties wrapped in soft-focus intimacy. In the years following Black Messiah, the textures and rhythm philosophies D’Angelo brought back to the center started to seep into how artists like Hynes approached their craft. Freetown Sound doesn’t enter neatly or loudly; it lives in fragmented conversations, delicate vignettes, and whispered declarations, stitched together as if overheard on city blocks or drifting through bedroom walls. Hynes embeds vocal samples, spoken-word clips, and piano flourishes that float atop percussion that doesn’t chase rigid structure, echoing Black Messiah‘s belief in pockets that breathe rather than snap. “Augustine” or “Hands Up” resist linear momentum, choosing instead a porous drift—an ambient politics that wraps subtle resistance and vulnerability into sonic textures. That quiet insistence—groove as shared emotion, memory as rhythmic fluidity—draws explicitly from D’Angelo’s lexicon. Where Black Messiah reignited communal feeling through loose instrumentation and rhythmic friction, Freetown Sound answers gently yet defiantly—a diasporic echo that translates and transforms the lineage, leaving behind whispers of the same purposeful tension.

Solange, A Seat at the Table

From its first breath, A Seat at the Table takes its time. It opens gently—soft keys, ghostly atmospheres, the pulse felt more than heard. That quiet urgency stems from Black Messiah’s belief that sound, space, and silence all carry political heft. D’Angelo’s re‑entry was not bombastic; it was exigent, intimate, a spiritual groove. Solange inherits that posture: the politics in her record don’t live in grand gestures always, but in voice, in pause, in restraint. Between songs like “Cranes in the Sky” or “Don’t Touch My Hair,” the band plays sparse, deliberate; you hear the space between bass and snare, the tail of reverb, the micro‑shifts in timing. Solange doesn’t overfill. She allows her voice to drift, to wait, to observe. That is a move traceable to Black Messiah’s spacing: D’Angelo often lets the instrumentation hang before reentry. Seat at the Table also picks up Black Messiah’s project of communal voice: backing vocals, call‑and‑response, and voices weaving. The politics of ancestry, of grief, of healing—Solange frames them in a groove that is textured but not aggressive, delicate but insistent. Her record extends the Black Messiah belief that the personal and the prophetic are not separate domains—they meet between notes.

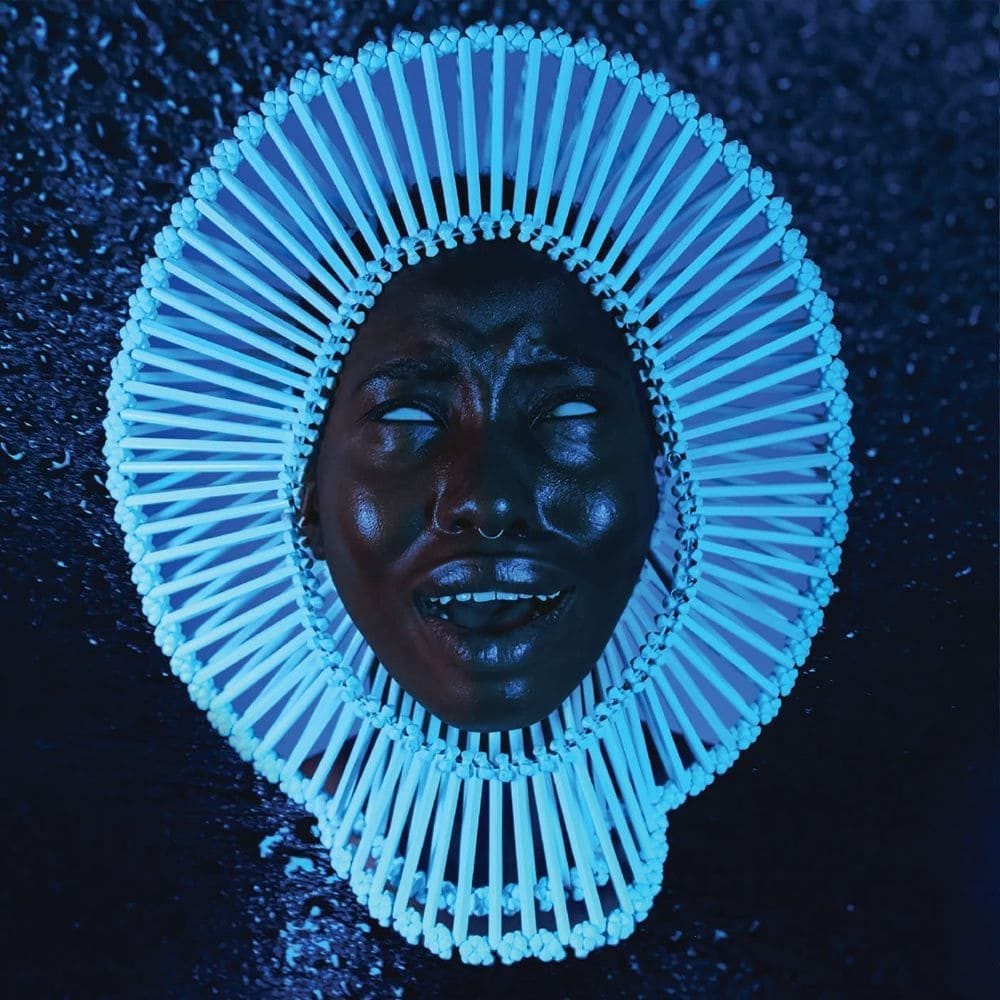

Childish Gambino, “Awaken, My Love!”

In Awaken, My Love!, Donald Glover takes a leap: he steps back from the rap mic and into a haunted, psych‑soul dreamscape. The record begins in that space beyond categorization—guitar squalls, slurred backing vocals, rolling kick drums that feel more breathed than hit. That opening posture already reflects Black Messiah’s insistence that you approach the groove obliquely, as something alive and unsteady. D’Angelo’s rebirth offered a map for vulnerability within muscle; Gambino reads it as permission. Hell, Questlove texted D late at night about how incredible the music was. When “Redbone” slinks forward, it does so at an angle: the drums push, then sag; the voice stretches beyond the bar, scuffs behind the beat. That micro‑drag sense is directly legible as a descendant of Black Messiah’s timing politics—notes allowed to hover between promise and release. And when the record erupts—“Me and Your Mama” rising into fervor—it feels like translation. Gambino takes Black Messiah’s template—the tension between prophecy and intimacy, between rupture and seduction—and reinterprets it through a theatrical frame. The solos, the echoy effects, the way the horns flicker in and out: it’s a version of D’Angelo’s approach, but bruised, theatrical, reimagined.

Nick Hakim, Green Twins

Nick Hakim occupies in Green Twins a space between confession and dream, stretching his voice into reverberant hollows and warping instrumentation into half-formed memories. That inwardness—and the elastic temporal logic behind it—is inherited from Black Messiah. D’Angelo’s record taught that meaning lives in what’s between beats, in ghost notes and harmonic shifts that refuse closure. On Green Twins, Hakim pulls the listener toward those margins. His drums sometimes slide behind, his vocal attacks sometimes drift ahead; chords bleed and fragment. Hakim channels classic soul (Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, even D’Angelo himself) but distorts those references, bending them through warped production and haunted space. On “Miss Chew,” sax bleeds into fractured textures while beat and bass hold tenuously; elsewhere, he uses reverb and layering to make voices sound overheard or receding. That tension—between audible and spectral, between meter and drift—is the same engine under Black Messiah. Hakim’s project is to find intimacy in that tension: to let his heartbreak, his devotion, his yearnings be shaped by a rhythm that doesn’t fully settle, just as D’Angelo’s regeneration insisted on ambivalence in the groove.

Chris Dave and the Drumhedz, Chris Dave and the Drumhedz

Chris “Daddy” Dave was already part of Black Messiah’s backbone—his drumming on that album helped define its elastic, unsteady heartbeat. When he stepped into his own name, he led a band and reclaimed the drum pocket as space and argument. On tracks like “Sensitive Granite,” he toys with odd meters, letting the snare land between beats; in “Whatever,” his sparse guitar and hip-hop drums interplay in tension that recalls the half‑drag, half-push of Black Messiah. But more than technique, Dave carries forward Black Messiah’s politics of rhythm: that drummers aren’t servants, they’re interlocutors. His compositions treat silence, feedback, and micro-timing shifts as textual. He doesn’t simply echo D’Angelo’s looseness—he radicalizes it: he amplifies the idea that groove is dialectic, that the pocket contains friction. On Drumhedz, you hear a lineage where the groove is both tender and resistive, and percussion becomes its own narrating voice, not just an answer to the voice or bass. The record feels like the satisfying consequence of the invitation Black Messiah extended to rhythm-makers to speak first.

Noname, Room 25

You’re coaxed into a hush when listening to Noname. The record’s voice, the beat, the life—it arrives as thought. That quiet insistence is a descendent of Black Messiah’s method of hiding power in softness. D’Angelo’s album taught that resilience could be in restraint, that tension could live between breaths. Noname’s record is conversational in flow, allowing spare instrumentation to breathe, letting the vocal phrase drift behind or ahead of the kick. The pocket is loose, micro‑lagged, and not locked. In this, she participates in Black Messiah’s time politics: not all moments align; meaning lives between them. Lyrically, Room 25 is interior politics, but implicitly relational: Black life in the city, love, alienation, community. In how she speaks—soft but firm—she channels Black Messiah’s blend of prophecy and tenderness. There’s no grand chorus screaming redemption; instead, there is patience, weight, calibrated space. In that bridging between voice and silence, Room 25 whispers back to Black Messiah, tracing not a mimic but a resonance path.

SAULT, Untitled (Black Is)

SAULT was already shrouded in mystery, less a band than a collective pulse radiating out of London’s Black creative underground. Their earlier projects had bent funk, soul, and dub into something tactile and modern, but this record dropped as a kind of open channel for the grief, rage, and affirmation surging through 2020’s protests. In the wake of D’Angelo’s Black Messiah, the very shape of the groove had been redefined—more elastic, more communal, and charged with political purpose. SAULT’s arrangements don’t settle for tight syncopation or classic R&B swing; they multiply percussion, stack chants, let the rhythm tumble and regenerate, insisting on movement that refuses resolution. Voices overlap and repeat as if in a ritual, songs bleed into one another, and the mood swings from rallying cry to prayer without warning. That willingness to let groove become the central organizing principle—to put the drums and the crowd at the center and let everything else orbit—is a direct continuation of the spiritual and structural priorities D’Angelo reawakened. Instead of looking backward, SAULT advances the lineage by proving that rhythm can still be a form of protest, healing, and presence—music as both shelter and megaphone, never tidy, always alive.

Pino Palladino & Blake Mills, Notes With Attachments

Pino Palladino’s bass work provided the rhythmic spine to Black Messiah, holding together grooves that purposely drifted in and out of stability. Years later, collaborating with producer Blake Mills, he brought that same intuitive philosophy forward into Notes With Attachments. Instead of relying on hooks, it trusts in inhabiting its textures—notes bend gently, instruments come and go unpredictably, and silence itself becomes structural. This musical grammar was clearly seeded in the Black Messiah sessions, where Palladino learned the power of allowing instruments to breathe rather than dominate. Mills’s experimental production adds atmosphere, further aligning with the analog warmth and deliberate imperfection D’Angelo championed. Instead of imitating Black Messiah, Palladino and Mills internalize its spirit, developing a vocabulary where rhythmic instability creates emotional depth. The resulting soundscape reaffirms the idea that the pocket between rhythm and silence, first revived by D’Angelo’s ensemble, remains fertile ground—open, inventive, and capable of speaking profound truths.