The Lineage of Michael Jackson (R&B Roots)

A young genius studied the masters before becoming one. MJ absorbed Jackie Wilson’s screams, Smokey Robinson’s falsetto, etc. Sixteen albums that shaped the King of Pop’s emotional vocabulary.

Michael Jackson stands alone, a singular figure whose impact on subsequent R&B artists remains incalculable. Yet even Michael absorbed technique from those who came before, digesting their styles and transmuting them into something unmistakably his own.

On the dance floor, he drew from Fred Astaire and the tap virtuosity of the Nicholas Brothers. As a total entertainer, he found a model in Sammy Davis Jr. Musically, he claimed influence from Jimmy, Gershwin, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie. But as an R&B vocalist, the artist he cited above all others was Jackie Wilson. Known as “Mr. Excitement,” the Detroit-born singer possessed a powerful, soaring high tenor and dance moves that blended explosive energy with urban sophistication. That all of this erupted from a slender frame must have electrified young Michael. The fact that Berry Gordy Jr. had written Wilson’s 1958 hit “Lonely Teardrops” before founding Motown adds another layer of destiny.

Alongside Wilson, James Brown loomed as a blinding presence in Michael’s childhood. The Godfather’s fierce vocals and footwork at the Apollo Theatre left their mark. Michael studied JB’s leg movements and mimicked his choreography. When the Jackson 5 auditioned for Motown (the session was filmed), one of the songs they performed was Brown’s “I Got the Feelin’.” Sam & Dave, the Stax duo nicknamed “Double Dynamite” for their scorching performances, also left an impression. So did Little Richard and Chuck Berry, the Black rock and roll pioneers whose ability to transcend racial barriers surely encouraged Michael. And of course, Motown itself provided the primary education. The Miracles, fronted by Smokey Robinson, captivated him especially. He sang their “Who’s Loving You” at his pre-signing audition and covered it on the Jackson 5’s debut album. Smokey’s crystalline high tenor clearly enchanted him.

Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye influenced Michael not just through their music but through their business example. Both had wrested creative control from Motown, a model for the independence Michael would later pursue. His connection to Stevie ran particularly deep. During the Motown years, Michael covered Stevie’s material repeatedly, sang backup on “You Haven’t Done Nothin’” with the Jackson 5, and contributed to “All Day Sucker” as a solo artist.

Beyond Motown, Michael’s R&B education included Sly & The Family Stone and Funkadelic’s funk experimentations, plus the Philadelphia sweet soul of the Delfonics and Stylistics. These influences surfaced throughout the Jacksons’ post-Motown work. Even African music left its trace. The chanted coda of “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” borrowed directly from Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa,” connecting Michael to a continental pulse that predated American popular music itself.

No ratings and an afterword description for this one.

Sammy Davis Jr., Something for Everyone

Sammy Davis Jr. arrived at Motown in 1970 as a refugee from the Rat Pack era, seeking younger ears and hipper currency. He found instead a mismatch wrapped in a gatefold sleeve. Arranged by Billy Strange and George Rhodes and produced by Jimmy Bowen, Something for Everyone placed the consummate showman against backdrops borrowed from Blood, Sweat & Tears and the Motown assembly line without quite belonging to either. The title proved prophetic in the wrong direction. Davis tears through “Spinning Wheel” with characteristic gusto, his brassy tenor cutting against horn charts that aspire toward contemporary rock-soul fusion. His cover of “In the Ghetto” carries genuine pathos, his voice bending around Mac Davis’s lyrics with a survivor’s intimacy. “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy” lets him stretch into gospel-tinged belting, organ swelling beneath him. These moments reveal an entertainer straining to meet the moment. The album captures the anxiety of transition. Davis understood that his audience was aging, that the kids wanted something grittier. His voice remained supple and committed, his phrasing intelligent. But covering contemporaneous hits couldn’t transform him into a contemporary artist. The album tanked, as the kids say, Motown shelved the Carnegie Hall recordings they’d made, and the partnership dissolved quietly. For a young Michael Jackson watching from the wings, the lesson was clear. Studying the past matters, but impersonating the present courts disaster. — B.O.

Jackie Wilson, Lonely Teardrops

Dick Jacobs’s arrangement of the title track opens with a guitar lick from George Barnes that became one of rock and roll’s primal gestures. Behind it, the Ray Conniff Orchestra and Chorus build a bed for Jackie Wilson’s voice to perform its particular miracle: making desperation sound like exultation. “My heart is crying, crying/Lonely teardrops,” Wilson sings, and somehow the phrase becomes a celebration of feeling anything at all. Berry Gordy Jr. and Roquel “Billy” Davis wrote most of this material before Gordy founded Motown, and you can hear the future taking shape. “That’s Why (I Love You So)” lays out the call-and-response patterns and gospel fervor that would define the Detroit sound. “Each Time (I Love You More)” shows how pleading could become its own form of seduction. The songwriting team understood that Wilson’s instrument could turn any lyric into physical experience. He wanted to be a total entertainer, not genre-bound. But the original material resonates strongest because it lets his voice do what no one else’s could. Brunswick captured something irreplaceable here. The sound of a man turning heartbreak into aerodynamics. — P

James Brown, Live at the Apollo, Volume II

Recorded over two nights in June 1967 and released the following year, this sequel to Brown’s legendary 1963 Apollo recording finds the Godfather at the peak of his powers and his paranoia. The band, rebuilt after mass defections, moves as a single organism. When Brown calls for the bridge, they hit it. When he screams, they catch him. Brown’s monologues between songs reveal the showman’s psychology. He flatters the audience, threatens them, seduces them. The band vamps while he preaches about respect, about excellence, about the necessity of sweat. These spoken passages, often edited from studio albums, prove essential to understanding the full experience. Brown wasn’t just performing music; he was conducting ritual. “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World” builds toward a climax that threatens to tear the Apollo’s rafters loose. The audience screams back at him, and you can hear the room vibrating with something beyond entertainment. This is church without the certainty, sex without the privacy, politics without the speeches. Michael Jackson studied these recordings obsessively. The stage became a battlefield, the performance a kind of warfare. Brown taught him that. — B.O.

James Brown, I Got the Feelin’

The record shares its title with the single the Jackson 5 performed at their Motown audition, and that choice reveals young Michael’s instincts. The song itself crackles with barely contained energy, Brown’s voice darting through the mix while Maceo Parker’s tenor saxophone punctuates and the rhythm section locks into a groove both minimal and maximal. Recorded during one of Brown’s most prolific periods, this collection suffers from the era’s approach to R&B albums as vehicles for singles surrounded by filler. A portrait of an artist treating the studio as gymnasium develops from these sessions. Brown worked constantly, releasing material at a pace that would have exhausted anyone else. Not everything connected, but the process itself generated momentum. The title track stands as one of his sharpest statements of purpose, a funk manifesto built on feel rather than theory, on body rather than mind. Michael Jackson grasped this instinctively. The audition tape shows him channeling Brown’s energy without merely copying it, finding his own physical vocabulary within the borrowed framework. — P

Sam & Dave, Double Dynamite

The nickname proved accurate. Sam Moore’s vulnerable tenor and Dave Prater’s rougher bark created friction that generated heat, their call-and-response rooted in church but aimed at the flesh. Backed by Booker T. & the M.G.’s and the Mar-Keys horns, with material primarily from Isaac Hayes and David Porter, this second album captures the Stax formula at its most potent. “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby” shifts the mood toward vulnerability. Moore’s vocal quivers with genuine emotion as he catalogues the symptoms of sympathy. The arrangement stays sparse, letting the voice carry the weight. This ability to pivot from exhortation to tenderness gave Sam & Dave their range. They could work a crowd into frenzy, then bring it back to earth with a ballad that felt earned rather than strategic. The duo’s animosity toward each other is well documented, but the music suggests something more complicated than hatred. Their voices knew each other too well for mere professional obligation. When Prater growls beneath Moore’s falsetto, you hear two men engaged in conversation only they fully understood. Michael Jackson achieved similar effects through studio technology, layering his own voices into dialogue. — B.O.

Little Richard, Here’s Little Richard

The opening syllables of “Tutti Frutti” announced a new world. Before those words, rock and roll existed as possibility. After them, it existed as fact. Richard Penniman, hammering piano at J&M Studio in New Orleans with Earl Palmer on drums and Lee Allen on tenor saxophone, created the template for everything that followed. The screams, the pounding eighth notes, the sense that the music might fly apart at any moment. Producer Robert “Bumps” Blackwell recognized what he had. The twelve tracks gathered here from sessions spanning 1955-1956 function as both historical document and visceral experience. “Long Tall Sally” makes a story about evasion sound like triumph. “Ready Teddy” turns readiness into a state of permanent anticipation. “Rip It Up” describes destruction as recreation. Every song runs at the edge of control. His significance extended beyond technique. Richard’s presence—flamboyant, gender-bending, unapologetically Black and unapologetically himself—created space that hadn’t existed before. Michael Jackson eventually occupied similar terrain, making androgyny into a kind of superpower. But Richard did it first, in Jim Crow America, with no template to follow. That courage echoes through every track, turning what could have been mere novelty into something approaching liberation. — P

Chuck Berry, Berry Is on Top

The title made a statement of fact. By mid-1959, Chuck Berry had spent four years constructing the vocabulary of rock and roll. The guitar riffs, the lyrical concerns, the performing persona that countless white boys would imitate. This third album gathers the evidence like a prosecutor presenting an airtight case. “Johnny B. Goode” needs no introduction, but it bears examination. The song tells the story of a country boy whose guitar playing will make him famous, turning autobiography into myth through third-person narration. Berry’s guitar introduction became the most copied riff in rock history. But the song’s genius lies in its universality. Anyone with a dream could hear themselves in that country boy. Berry made aspiration sound like destiny. The future soul legend absorbing Berry’s rock and roll mastery represents one of those crossroads moments where musical history folds in on itself. Michael Jackson achieved similar synthesis, absorbing Berry’s showmanship along with Wilson’s acrobatics and Brown’s intensity. Berry Is on Top proves that before synthesizers and multi-tracking, guitar and attitude could conquer the world. — B.O.

The Miracles, Hi... We’re the Miracles

Motown’s first family introduced themselves with appropriate modesty. The title acknowledges the group’s newcomer status even as the music announces ambitions that would reshape American popular song. William “Smokey” Robinson’s falsetto, already distinctive, threads through arrangements that balance doo-wop tradition with Berry Gordy’s emerging production philosophy. “Shop Around” became Motown’s first million-seller, and its inclusion here makes the album essential. Robinson’s voice slides through advice about romantic caution, the tempo moderate, the message clear. The song proved that Black pop could address practical concerns as effectively as it expressed desire. Young consumers were getting counsel along with entertainment. “Who’s Loving You” arrived with different weight. Robinson wrote it as an exercise in emotional devastation, and his vocal delivery matches the lyrics’ despair. When Michael Jackson performed this at his Motown audition, he was choosing to measure himself against Robinson’s standard. His version, recorded at age eleven, somehow approached the original’s pain while adding childish bewilderment that made the emotion more piercing. The boy from Detroit who would become Michael Jackson’s mentor in romantic balladry was honing his craft. These early sketches would develop into masterpieces, but the draftsmanship is already visible. — P

Stevie Wonder, Fulfillingness’ First Finale

The title promised an ending that wouldn’t arrive for years. Stevie Wonder had negotiated full creative control from Motown, nearly died in a car accident, and emerged with three consecutive masterpieces. “You Haven’t Done Nothin’” opens with clavinet snarl and pointed disgust. The Jackson 5 provide backing vocals as Wonder indicts the Nixon administration without naming names. The funk is ferocious, the moral clarity bracing. After the relative introspection of Innervisions, this announcement of political engagement surprised and thrilled. “Creepin’” shifts the mood toward late-night vulnerability. Wonder’s vocal floats over sparse arrangement, the Fender Rhodes providing harmonic cushion. “Too Shy to Say” continues the intimacy, with James Jamerson’s bass and “Sneaky” Pete Kleinow’s pedal steel creating an unlikely sonic environment. These quieter moments prove Wonder’s range beyond the singles. Michael Jackson’s own struggles with mortality and meaning found similar expression, though in different musical language. Wonder provided the model. Popular music could address ultimate questions without abandoning accessibility. — B.O.

Stevie Wonder, Hotter Than July

The commercial failure of Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants had humbled the seemingly infallible Wonder. Hotter Than July represents strategic retreat as much as creative advance, the sound of a genius ensuring his audience wouldn’t abandon him. That calculation doesn’t diminish the music. It contextualizes the music. “Master Blaster (Jammin’)” announces the approach with reggae rhythms filtered through Wonder’s synthesizer palette, lyrics celebrating Bob Marley while avoiding the Jamaican’s revolutionary content. The groove is undeniable, the politics safely celebratory. Michael Jackson provides backing vocals, appearing on a Wonder record for the first time as an adult peer rather than child protégé.

“Rocket Love” employs space travel as metaphor for romantic disappointment, the Fender Rhodes arpeggios descending like a spacecraft returning to earth. Wonder’s vocal conveys genuine hurt beneath the clever conceit. GZA sampled this track for “Cold World,” recognizing the melancholy buried in the arrangement. “Happy Birthday” accomplishes something few pop songs manage. Genuine advocacy. Wonder wrote it to support the campaign for a Martin Luther King Jr. federal holiday, and the song’s relentless cheer masks serious purpose. The gatefold sleeve contained a petition and historical photographs, turning the record into an artifact of activism. Whether the song convinced any congressional votes remains unclear, but its existence proved that Wonder’s commercial instincts could serve political ends. The holiday was established three years later. — P

Marvin Gaye, What’s Going On

Berry Gordy didn’t want to release it. The Motown founder heard jazz pretension and political risk where history would hear breakthrough. Marvin Gaye refused to record anything else until his vision reached the public. The standoff ended when sales vice president Barney Ales shipped 100,000 copies without Gordy’s knowledge. Within a week, demand required another pressing. The record plays as continuous suite, songs bleeding into each other through ambient sound and instrumental echoes. David Van De Pitte’s orchestrations wrap the Funk Brothers’ rhythm section in strings and horns that suggest both classical ambition and soul tradition. Gaye’s multi-tracked vocals create the impression of inner dialogue, the singer arguing with himself about politics, ecology, faith.

“What’s Going On” addresses a returning Vietnam veteran’s confusion. “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” catalogs environmental destruction before most Americans had heard the word ecology. “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)” turns economic despair into groove, the music’s warmth offsetting the lyrics’ desperation. Each song connects to the others, creating an architecture of concern. The influence on Michael Jackson extended beyond music to business model. Gaye had demanded and received creative control, proving that Motown’s assembly line could accommodate individual vision. When Michael sought similar freedom, he had Gaye’s precedent to cite. What’s Going On showed that commercial success and artistic ambition need not conflict, that popular music could address the world’s troubles without abandoning the world’s ears. — B.O.

Sly & The Family Stone, Stand!

The band that performed at Woodstock days after this release embodied integration as practice rather than theory. Black and white, male and female, Sly Stone’s collective made unity sound like the most natural thing in the world. The title track’s opening command lays out the stakes. This music demands action, not passive consumption. “Everyday People” entered the culture as nursery rhyme and stayed as anthem. The phrase “different strokes for different folks” entered common usage. Sly’s vocal trades between weariness and hope, the arrangement minimal enough to let the message breathe. The song reached number one as America fractured over Vietnam, civil rights, and generational conflict. It offered not solution but stance.

“Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” confronted racial tension directly, its title functioning as both insult and instruction. The extended groove lets the phrase repeat until meaning dissolves into sound and rebuilds as challenge. “Sex Machine” stretches past thirteen minutes, the band locked into a jam that predicts the extended workouts of Parliament-Funkadelic. The optimism here would curdle into the paranoid murk of There’s a Riot Goin’ On within two years. But Stand! captures a moment when integration seemed possible, when different people dancing together might constitute political action. Michael Jackson absorbed this lesson deeply. His videos presented racial harmony as choreographed fact, diverse dancers moving as one body. The vision originated here, in San Francisco studios where a pimp’s son assembled the future. — P

Funkadelic, Funkadelic

George Clinton’s collective was born from the doo-wop harmony group the Parliaments and immediately began dissolving categories. This debut drops listeners into a soundworld where psychedelic rock, deep funk, and street-corner vocals coexist without resolution. Nothing sounds quite like anything else. Everything sounds like the future. The answer comes from the first track through sound. Wah-wah guitar, phased drums, vocals that range from croon to scream. Eddie Hazel’s guitar work throughout marks him as one of rock’s underrated visionaries, his tone thick and searching. “I Got a Thing, You Got a Thing, Everybody’s Got a Thing” reduces philosophy to nursery rhyme while the music complicates the simplicity. What Is Soul?” asks another fundamental question, answering with testifying vocals over churchy organ. Clinton understood that funk was theology as much as technique. Funkadelic sounded like a band discovering itself in real time because that’s exactly what was happening. Michael Jackson achieved similar effects through meticulous studio construction, simulating spontaneity through technology. Clinton proved the feeling could emerge from actual chaos. — B.O.

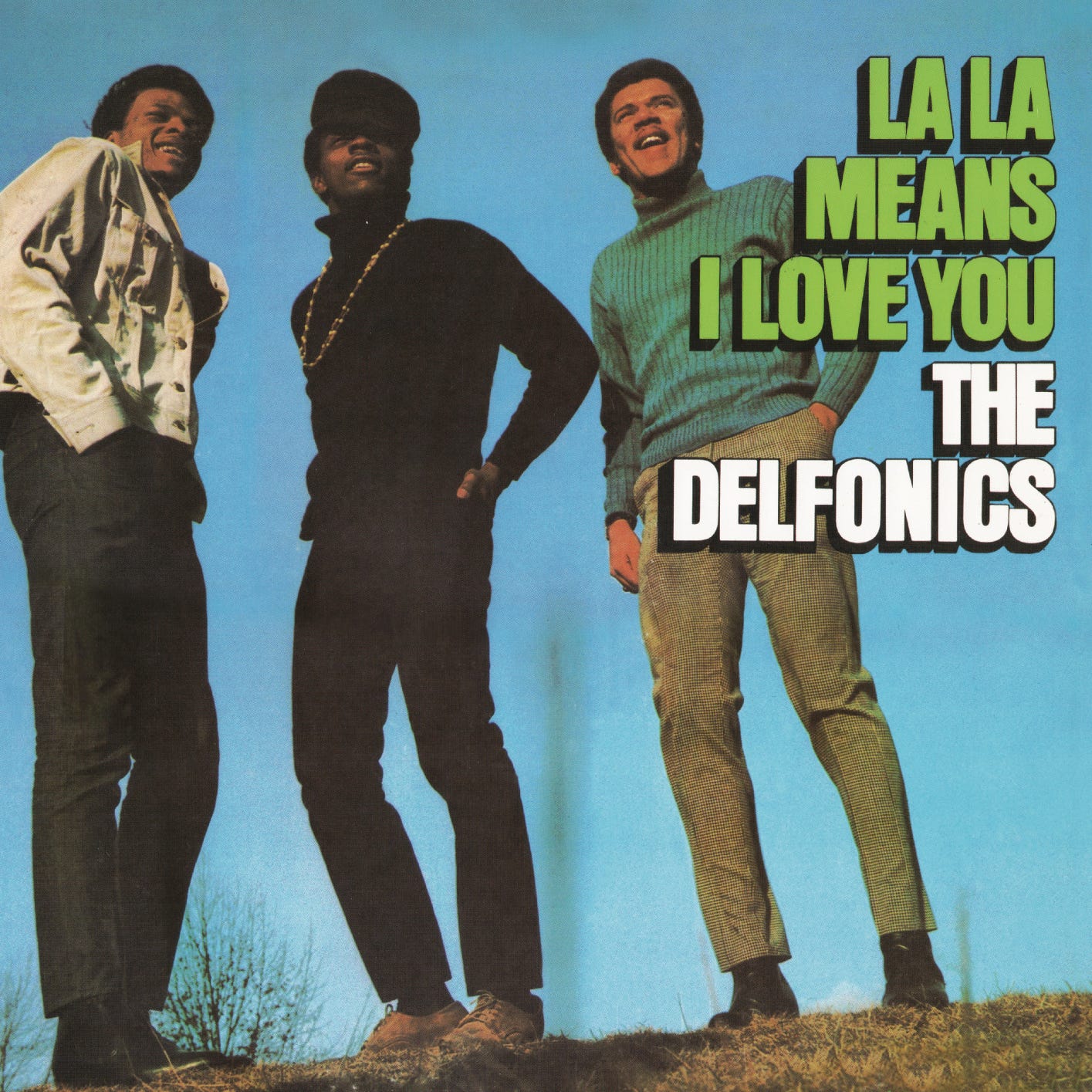

The Delfonics, La La Means I Love You

Philadelphia sweet soul reached early apotheosis with this debut from William Hart, Wilbert Hart, and Randy Cain. Producer Thom Bell’s arrangements set templates that would define the city’s sound through the next decade. Strings swooping through minor keys, drums cracking with precision, voices floating above the orchestration like incense. The title track’s “la la” hook reduced language to pure vocalization, emotion beyond words. William Hart’s falsetto carries the melody while his brother and Cain provide harmonic foundation. “Break Your Promise” and “Ready or Not Here I Come” prove the group’s consistency. Each song works within similar sonic parameters. The strings, the drums, the falsetto lead. What varies is emotional shade. “Somebody Loves You” suggests contentment; “Trying to Make a Fool of Me” expresses suspicion. The limited palette forced concentration, each element earning its place. This approach to soul—lush, romantic, aimed at lovers rather than dancers—influenced Michael Jackson’s ballad work throughout his career. “She’s Out of My Life” and “Human Nature” work in Philadelphia territory, the ache aestheticized through careful production. Bell and the Delfonics proved that vulnerability could sell, that male falsetto need not suggest weakness. — P

The Stylistics, The Stylistics

Russell Thompkins Jr.’s falsetto could have shattered glass or hearts; he chose hearts. This self-titled debut, produced by Thom Bell and arranged with Linda Creed’s lyrics, extended the Philadelphia sound toward its commercial peak. Where the Delfonics aimed for the bedroom, the Stylistics aimed for the wedding chapel. “Stop, Look, Listen (To Your Heart)” sets the template. Acoustic guitar arpeggios give way to full orchestration, Thompkins’s voice ascending through the arrangement like a soul leaving its body. Bell’s production surrounds the singer with cushion, every element precisely placed.

“You Are Everything” became the group’s signature, its declaration of devotion so absolute it risks parody. But Thompkins sells it through committed vocal performance, his falsetto conveying sincerity rather than sentimentality. The song has been covered countless times, each version measuring itself against that original conviction. The consistency can verge on monotony. Every song occupies a similar tempo, a similar key, and a similar emotional register. Bell and Creed had found a formula and exploited it thoroughly. But within those parameters, the craftsmanship rewards attention. Michael Jackson studied this precision. His ballads displayed similar attention to detail, each element serving the whole rather than competing for attention. — B.O.

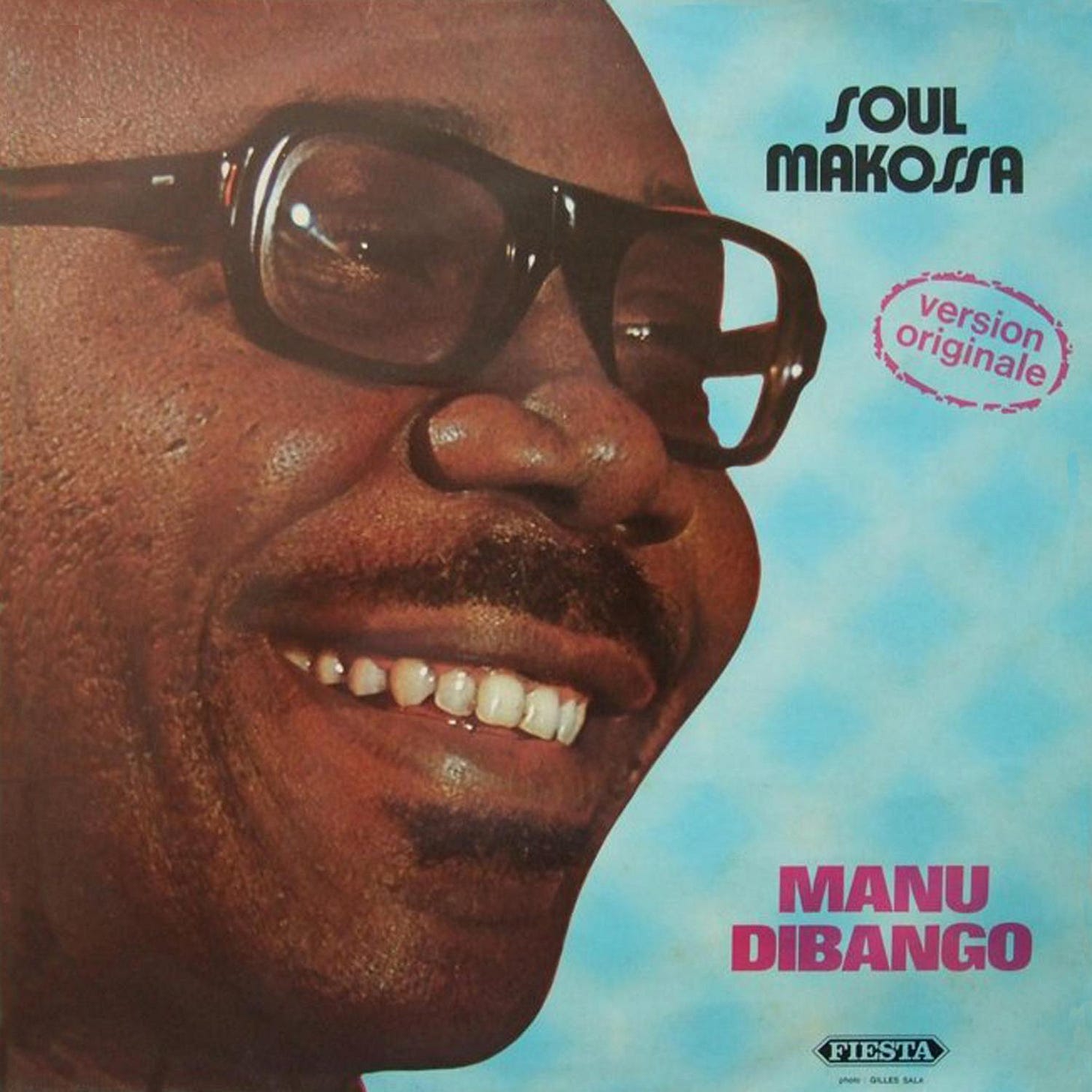

Manu Dibango, Soul Makossa

The title track arrived in America through import bins and adventurous DJs, its Cameroonian funk creating a sensation before most listeners could have found the country on a map. Manu Dibango’s saxophone rides a rhythm pattern that would surface, unauthorized, in Michael Jackson’s “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’.” The loop’s journey from Douala to Thriller traces one path through the African diaspora’s musical conversation. “Soul Makossa” itself builds from polyrhythmic foundation, the bass and drums laying a pattern that supports without constraining. Dibango’s sax enters with a figure that splits the difference between jazz phrasing and pop hook. The chanted vocal breakdown—”mama-say, mama-sa, ma-ma-ko-ssa”—works as pure phonetic pleasure, meaning secondary to sound.

The remainder of the record finds Dibango exploring various fusions. “Lily” employs funk guitar and synthesizer alongside traditional percussion. “New Bell” suggests Afrobeat’s heavier grooves. None matches the title track’s immediate impact, but together they document an artist bridging continents through sound. When Jackson interpolated “Soul Makossa” for Thriller, Dibango sued and settled. The legal outcome matters less than the musical evidence. African rhythm had always underwritten American popular music, but Dibango made the connection explicit. Jackson’s use of the chant tied the biggest album in history to a specific continental source. Whether that constituted theft or tribute remains debatable. That it completed a circle seems undeniable. — P