The Lineage of Voodoo (The Forgotten Gems)

We introduce 10 albums that seem to sit under the influence of Voodoo. Although it could take us forever to list the rest, it goes from 2017 and beyond, carrying D’Angelo’s spirit.

What’s happenin’, it’s Phil.

D’Angelo’s premature death at 51 came as a bolt from the blue. Ideally, we would have wanted to celebrate the 30-year milestone of his debut with the release of a new album that his close ally Raphael Saadiq had spoken about.

2025 is not only the 30th anniversary of Brown Sugar’s release, but also the 25th anniversary of Voodoo. Brown Sugar sparked countless followers, and by the time people began calling that cohort neo-soul, Voodoo had already reached an entirely different dimension. The influence this album has had on the quarter-century of music since its release is immeasurable. When it came out, I had already developed a kind of immunity to D’Angelo’s extraordinary gifts through Brown Sugar, so I didn’t find it especially difficult, but I did get the impression that he had headed even deeper toward the fundamental core of Black music.

When people talk about Voodoo, the standard refrain is the rhythmic “displacement.” At Electric Lady Studios in New York, the Soulquarians (D’Angelo, Questlove, James Poyser, J Dilla) kept piling up sessions while getting fired up on things like Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat. Out of that came a groove created by Questlove playing J Dilla’s lurching beat, the so-called drunken beat, loosely by hand. If you need a comparison, the idea is close to distressed jeans that are deliberately dirtied and torn to bring out a vintage feel. It’s an anti-establishment pose that pushes back against existing rules and common sense, while also throwing the essence of jeans into relief: they were workwear meant to be fine even if they got dirty or ripped. D’Angelo is similar. By deliberately bringing out a kind of “imperfection” like displacement and warp, he returns to something fundamental in humans, who are not machine-perfect, and seeks a pure soul with a sensibility that can even cherish human error. Voodoo was that, played with the members of Soultronics, including Pino Palladino, Roy Hargrove, and Chalmers “Spanky” Alford, among others.

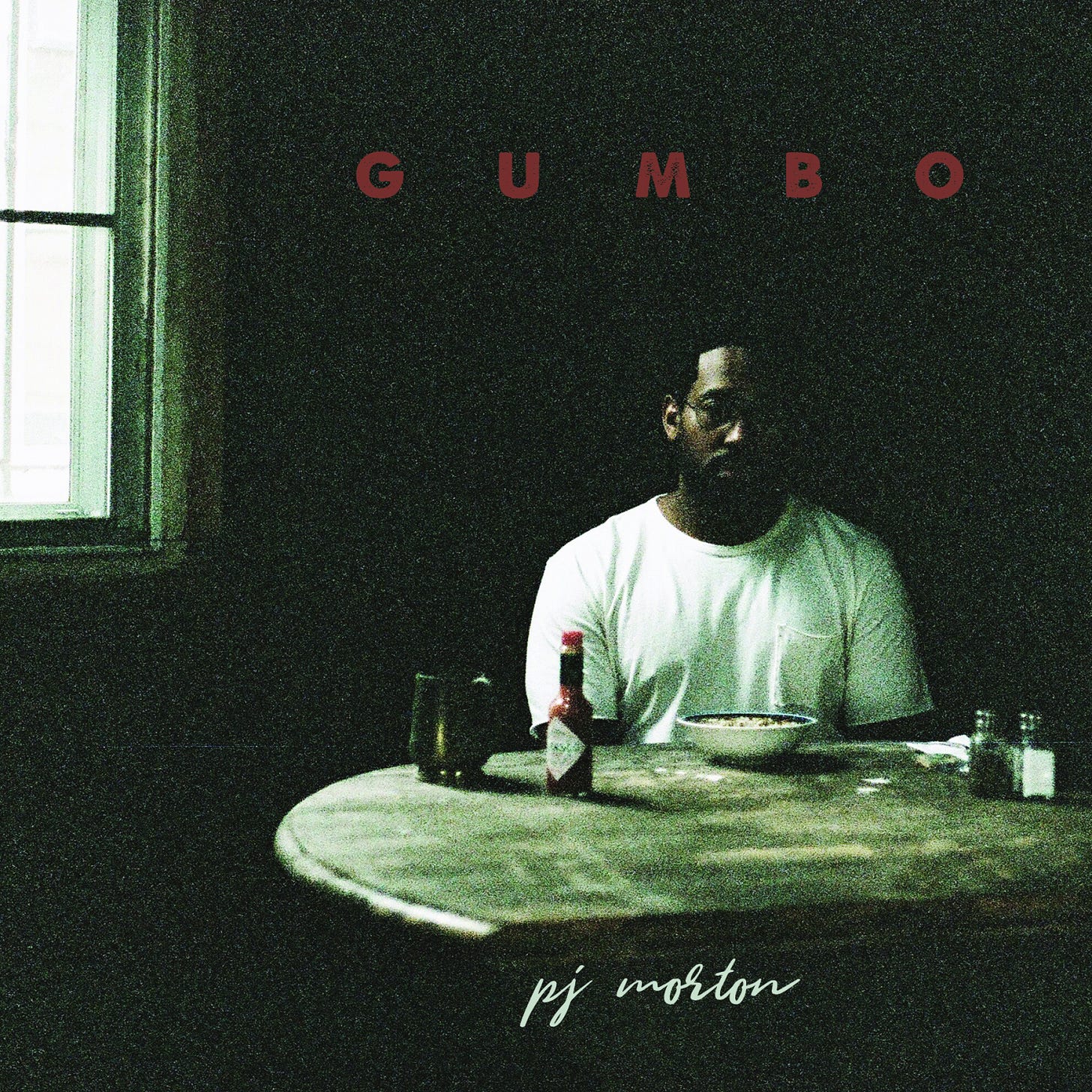

PJ Morton, Gumbo

A keyboard-playing singer/songwriter, rooted in gospel, and, like D’Angelo, the son of a pastor. After moving from place to place, including joining Maroon 5, the New Orleans native known as PJ Morton returned home and released an album named after his hometown’s famous soup. His devotion to Stevie Wonder is also conspicuous, but the Afrobeat-leaning funk “Sticking to My Guns” calls to mind the groove of “Spanish Joint.” The clincher is “Everything’s Gonna Be Alright,” which springs to life on a rhythm that feels as if Soultronics has possessed it. The Hamiltones, who appear here with BJ the Chicago Kid, are the junior protégés of Anthony Hamilton, who participated in the Voodoo tour.

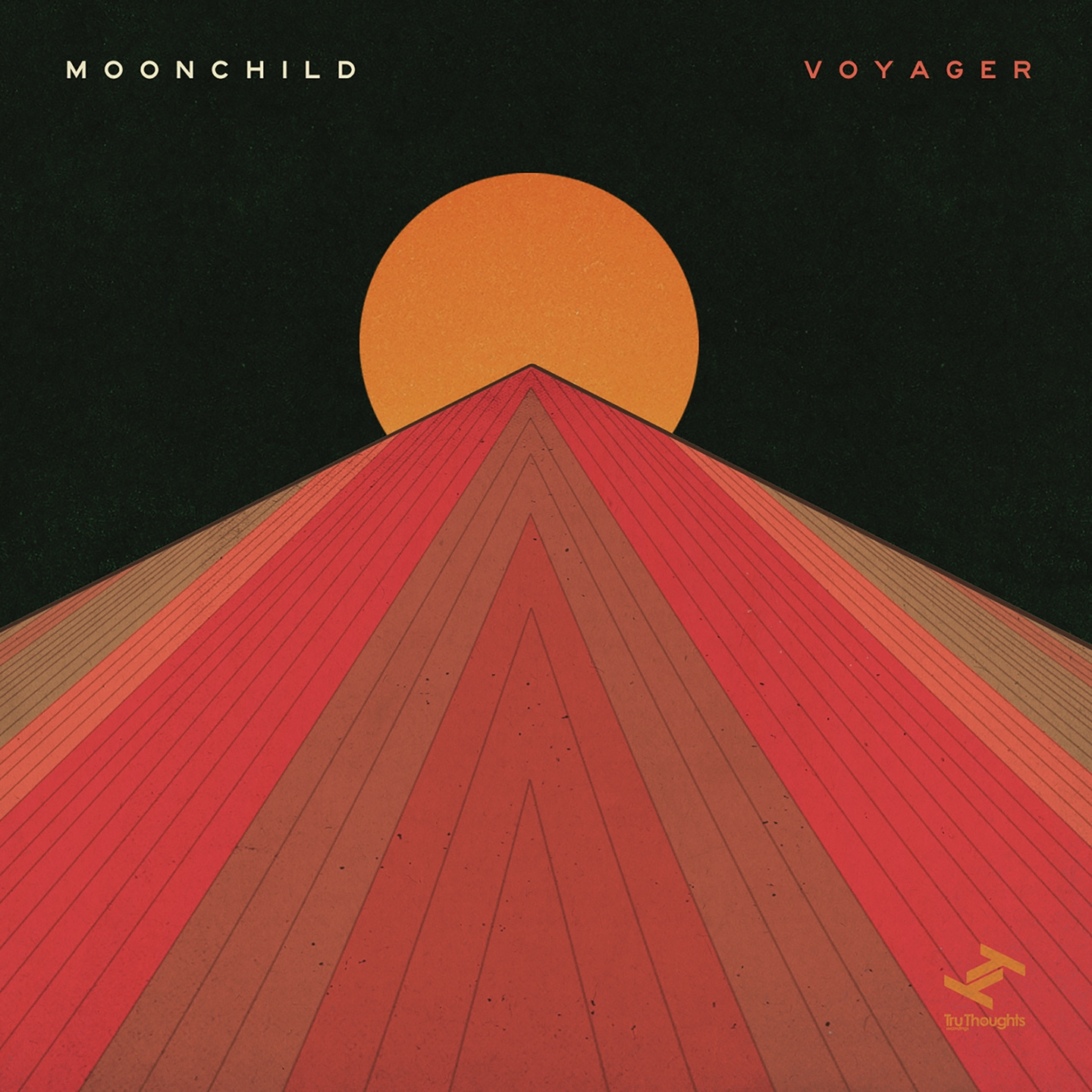

Moonchild, Voyager

The LA trio who issued a memorial statement saying, “Moonchild wouldn’t exist without D’Angelo.” Approaching neo-soul from the jazz side, and mixing in horn performance that connects to Roy Hargrove while being involved with figures like James Poyser, they carry a strong Voodoo influence on this record as well. In particular, the displaced rhythms on “Every Part (For Linda),” “Hideaway,” and “Doors Closing” are straight from the Soulquarians to Soultronics line, and the drunken beat on “Run Away” can make you mistake it for J Dilla’s, the unsung hero in Voodoo’s shadow. They’ve also said that “The List” was influenced by the drum groove of “Sugah Daddy” from Black Messiah.

Chris Dave and the Drumhedz, Chris Dave and the Drumhedz

Chris Dave, in earlier days, worked alongside Mint Condition, then came through the Robert Glasper Experiment, and also played with D’Angelo at the Vanguard. Often said to recreate J Dilla’s beats by hand, he made a project with Pino Palladino and Isaiah Sharkey, who were with him at the Vanguard, plus contributors to D’Angelo’s work like James Poyser and Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and you can guess what that adds up to. With Kendra Foster’s guest appearance, it strongly feels like it comes after Black Messiah, but that album itself had the lingering scent of Voodoo anyway. I want you to listen to “Spread Her Wings” (sung by Bilal and Tweet), where the rhythm is displaced all over the place.

SAULT, Untitled (Black Is)

SAULT is led by UK prodigy Inflo, who also contributed to Little Simz’s rise, is known for being prolific, in contrast to D’Angelo’s sparse output. Including the very title that calls itself “Untitled,” this work was inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement (and its resurgence), and you can feel an edge that connects to Black Messiah in tracks like the distorted “Monsters.” But on “Bow,” featuring Michael Kiwanuka, the way it approaches the deepest layers of Black music by basing itself in gospel while also mixing in Afrobeat is closer to Voodoo, too. It also shouldn’t be just my imagination to sense “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” in the slightly displaced triplet ballad “Hold Me,” sung by Cleo Sol, Inflo’s partner both publicly and privately.

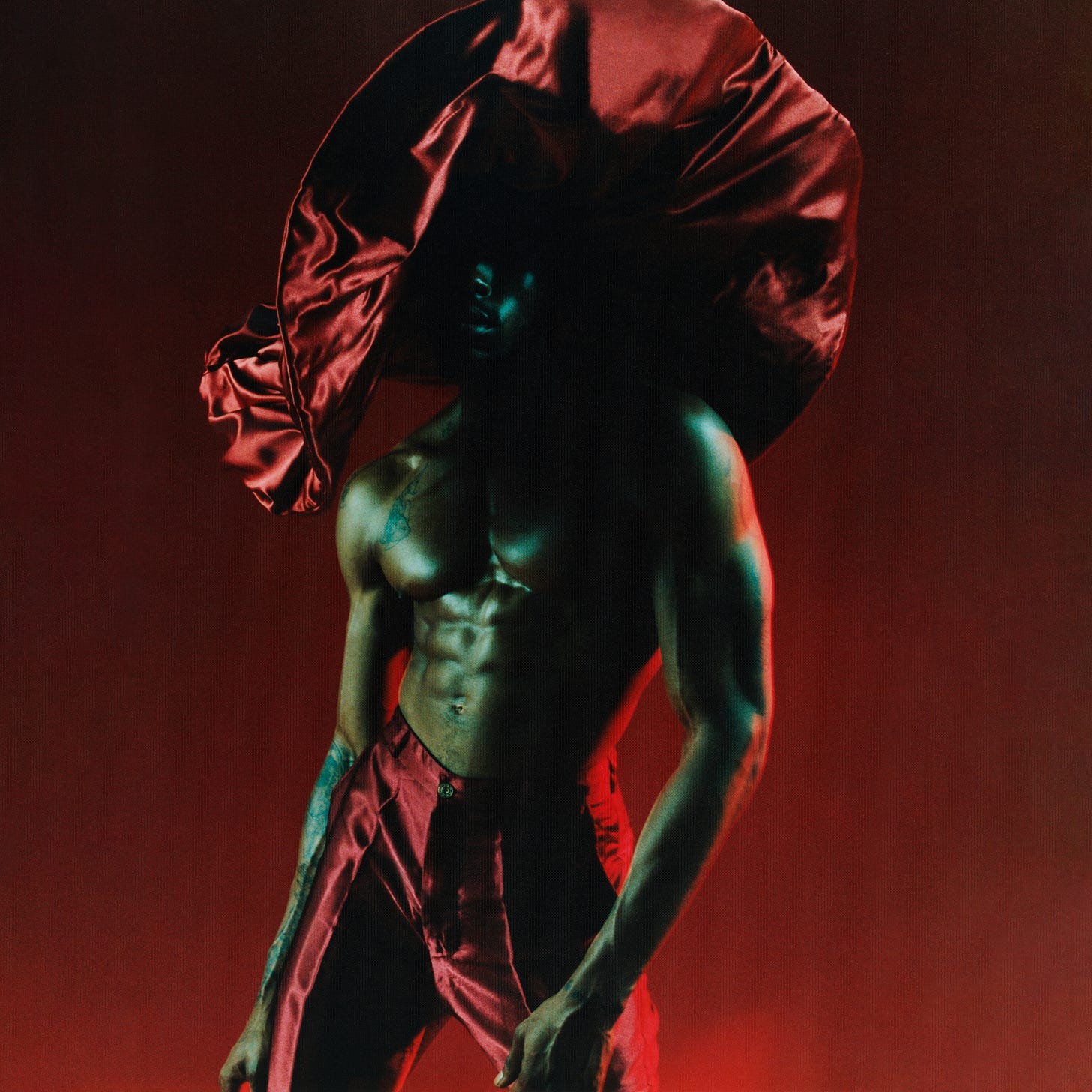

Jerome Thomas, That Secret Sauce

This self-contained singer from East London was already being seen, as early as his first EP Conversations (2016), as a kind of D’Angelo return, known as the Shatter the Standards favorite with Jerome Thomas. His smoky, sticky vocal that sometimes slips into falsetto, and his layered choruses, recall D’Angelo, and further back, Marvin Gaye. With his bronzed upper body bared, he sings organic, laid-back soul here as if searching for a midpoint between Brown Sugar and Voodoo. “No BS” and “Thanks, No Thanks” are typical examples, and “Settle Down,” including its rhythm guitar, brings “Chicken Grease” to mind while giving off the mood of “Brown Sugar.”

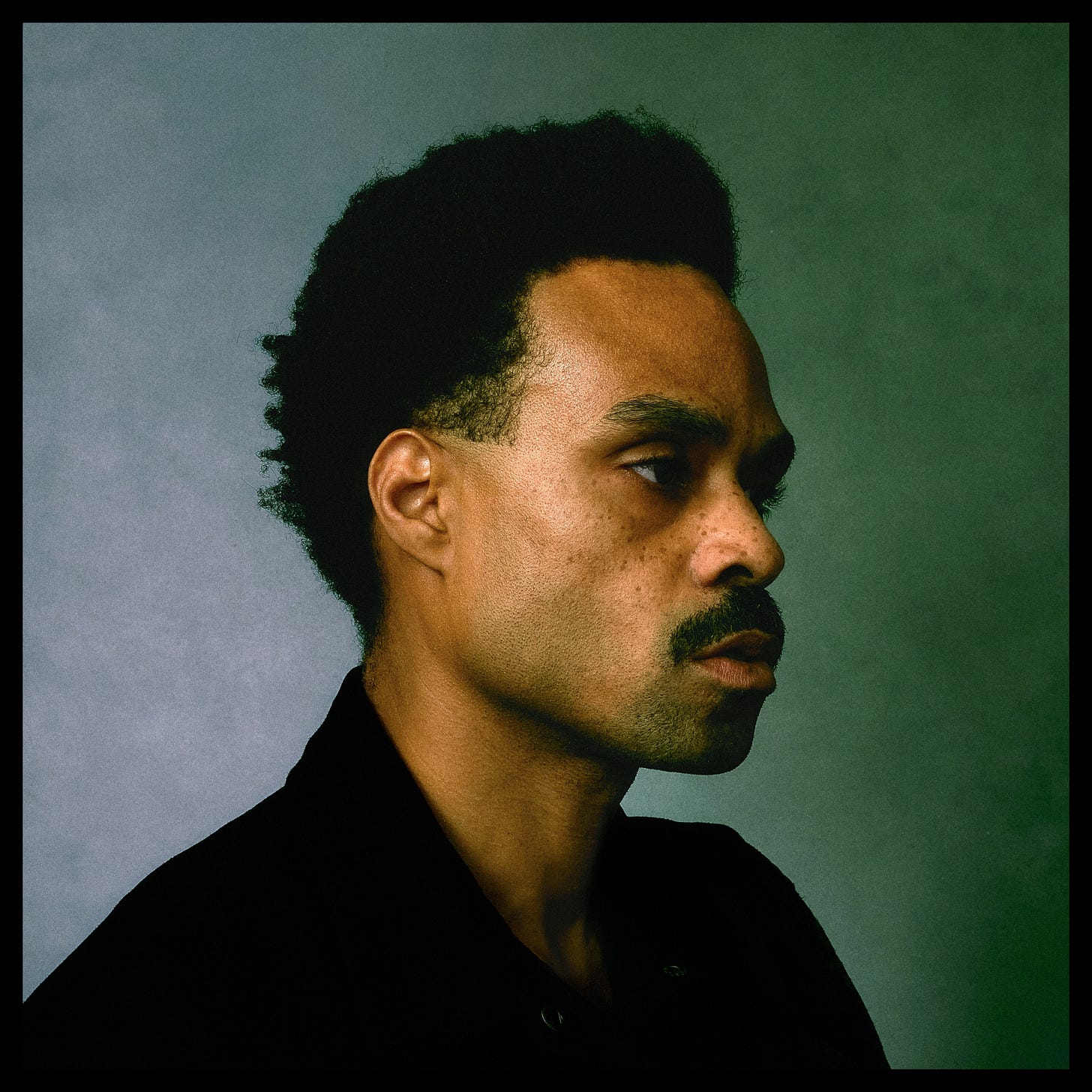

DJ Harrison, Tales from the Old Dominion

Like D’Angelo, DJ Harrison is from Richmond, Virginia, and is the leader of Butcher Brown, active out of that city. He has named Voodoo as a go-to favorite, and his group has performed a cover of “Brown Sugar.” His leader album, too, naturally plays with Voodoo’s displaced rhythms as if they were standard equipment, while keeping cosmic sonics and boom-bap-like beats as its base. That’s especially clear on “Country Fried,” and when the next track’s title is “Have You Ever Been (to Electric Ladyland),” it becomes hard to avoid the association. His cover of Roy Ayers’ “Coffy,” featuring Nigel Hall, is the kind of cover that makes you imagine: what if D’Angelo had done that song on Voodoo?

Sly Johnson, 55.4

Not Syl Johnson, but Sly Johnson. A French singer who originally started as a beatboxer. His “fourth solo album made in 55 days,” after having brought in Slum Village on his 2010 release 74, is filled from start to finish with Voodoo flashing across your mind: rhythmic displacement, gaps of silence, a hard beat that connects to DJ Premier (“Devil’s Pie”), glossy vocals that include falsetto, and an Afrocentric attitude. His covers of DJ Rogers’ “Trust Me” and Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” show not just good song selection, but a groove that feels as if Soultronics played it, and you can sense his longing for D’Angelo. It is, exactly, soul/funk built on hip-hop.

Shunské G, Gentle Reminder

The first solo work by the lead vocalist of the Japanese soul band Shunské G & The Peas. From the opening, displaced rhythm and his trademark D’Angelo-like mumbling vocal delivery jump out, and the English-lyric slow groove “Deepest Forest” carries the same atmosphere. But even while keeping J Dilla in mind, it doesn’t end at surface-level imitation. Having trained his voice in a gospel choir at a church in Pasadena, a suburb of LA, he pursues soul and funk while also putting forward his love for hip-hop and blues. More than the style of sound, the attitude is D’Angelo-like. The ballad “Contradiction,” which he said he conceived with “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” in mind, also resonates at a deeper level.

Bilal, Live at Glasshaus

A Philly native eccentric from the Soulquarians orbit, and also a schoolmate of Robert Glasper, Bilal became a bridge between soul and jazz in the 21st century in a position you might call “D’Angelo’s alternative.” In this live show planned by a Brooklyn venue in New York, he lays his voice over a thrilling performance by Questlove, Glasper, and Burniss Travis, and also shares the stage with Common while looking back over the 20-plus years he has walked through. The Soulquarians corner that runs from three straight J Dilla-produced songs into Questlove’s reminiscence talk, plus breakout tracks like “Soul Sista” and “Sometimes,” once again shows that Bilal was the closest “child” to have branched out from Voodoo.

Isaiah Sharkey, Red

A Chicago-born guitarist who succeeded his late mentor Chalmers “Spanky” Alford, a member of Soultronics, and supported D’Angelo as part of the Vanguard band. On this latest work, released two months before D’Angelo’s passing, he presents progressive soul/funk with sweet singing over psychedelic sonics that call Black Messiah to mind, starting right from the opening “Game of Life.” “Angel” feels like Daru Jones playing DJ Premier’s (“Devil’s Pie”) beat by hand. His Vanguard bandmate Keyon Harrold, who guests here, is also a successor-like presence to the late Roy Hargrove, so it’s an album that’s like Voodoo’s grandchild.

Sweet. I'm looking forward to digging into the albums here that I'm unfamiliar with, thank you!