The Parallels Between Everything Is Everything and To Be Young, Gifted, and Black

Their works remind us that the path from block party to Broadway and from choir loft to picket line is a single braided road, still inviting us to march, dance, write, and sing alongside them.

Donny Hathaway opened his 1970 debut with a joyful call-and-response that promised interconnectedness and followed it with nine performances that braid gospel urgency, street reportage, chamber-soul elegance, and intellectual rigor. The album arrived only a year after To Be Young Gifted and Black, the posthumous mosaic of Lorraine Hansberry’s letters, speeches, and scenes, and the two works share a restless drive to catalogue the fullness of Black life, to insist on dignity while naming danger, and to invite their audience into collective authorship. Hathaway literally cites Hansberry by recording Nina Simone’s anthem in her honor, yet the kinship goes deeper—both projects turn private testimony into public scripture, anchor cultural memory in accessible art, and argue that survival demands both critique and celebration.

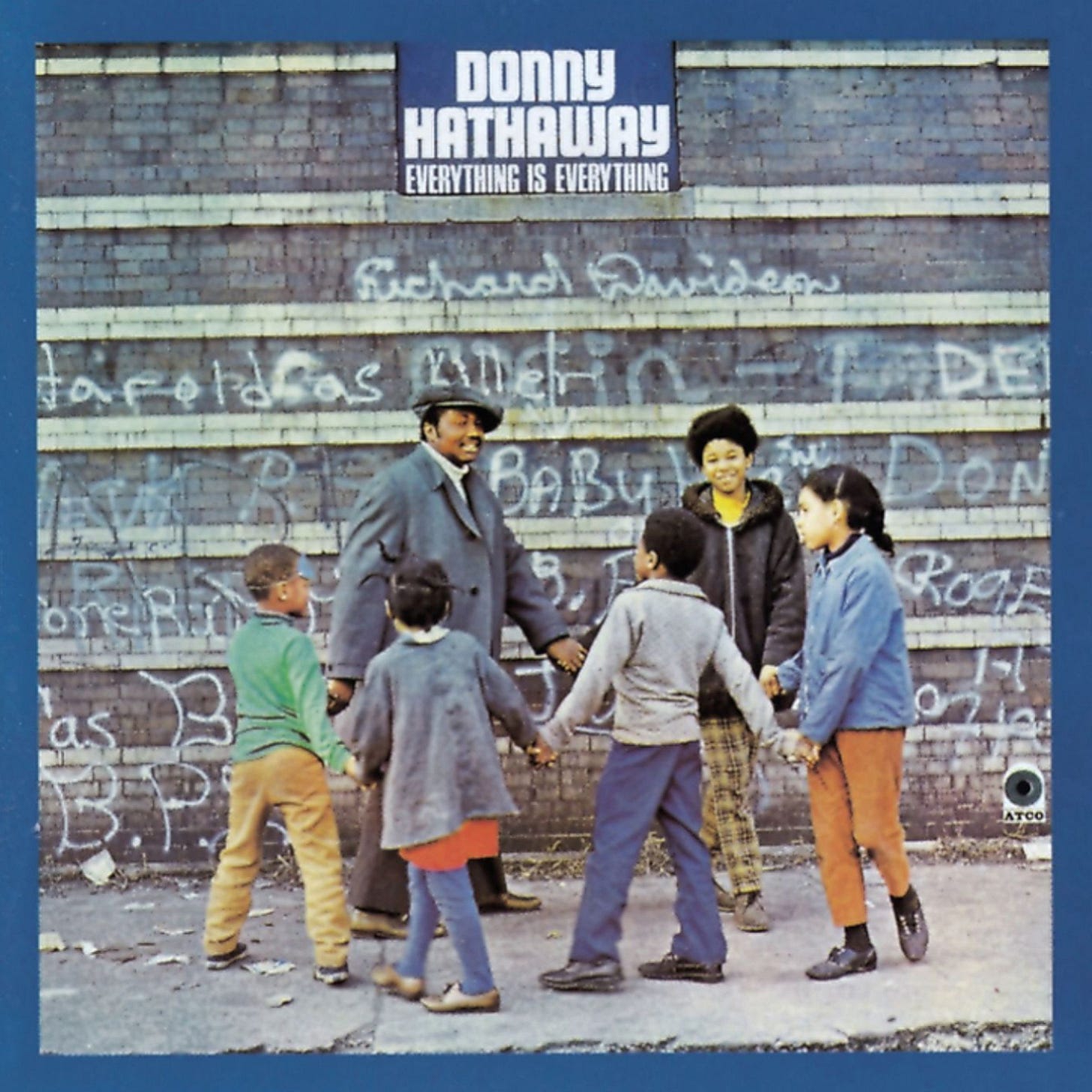

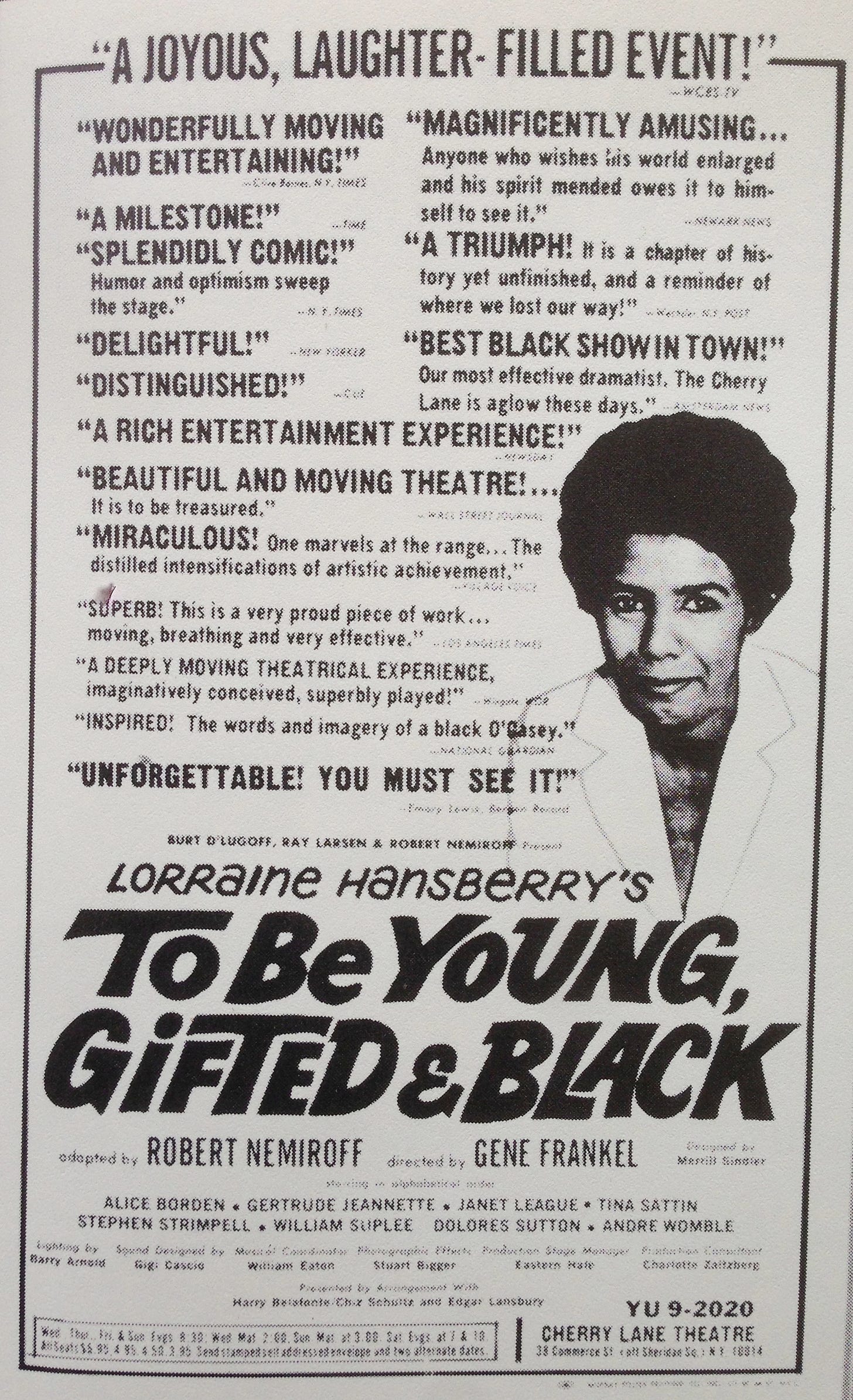

Hathaway entered Atlantic’s studio after years of arranging and piano work at Curtom Records with Curtis Mayfield, determined to “say certain things that were not possible while we were together.” The resulting album was cut between September 1969 and April 1970 and released on July 1, 1970, fifty-five years ago, people. Hansberry’s collection was assembled by Robert Nemiroff after her 1965 death and published in 1969, featuring speeches such as her 1964 address to teenage writers, which coined the phrase “young, gifted and Black.” Both works, therefore, surface from the same historical moment—post-Civil Rights Act optimism tempered by urban uprisings and Vietnam-era disillusionment—and both treat that moment as raw material rather than a backdrop.

To Be Young Gifted and Black is not a linear autobiography. It leaps from Chicago childhood to Greenwich Village salons to scenes from the Broadway rehearsals of A Raisin In the Sun, creating what reviewers called a “kaleidoscopic effect” that confronts “the complexity, beauty, joy, and courage of Black life.” Hathaway mirrors that structure by sequencing his album as a suite rather than a set of singles. “Voices Inside (Everything Is Everything)” layers choir shouts, horn stabs, and studio chatter, allowing the form to evoke a neighborhood block-party improvisation. The mid-album instrumental “Sugar Lee” shifts to organ-led groove, then immediately yields to the protest lament “Tryin’ Times,” whose lean arrangement underlines urgent lyrics about riots and unemployment. The constant stylistic pivots invite listeners to experience multiplicity, much like Hansberry’s montage, which is proof that no single genre or scene can fully contain Black consciousness.

Hansberry’s book frequently shifts from a first-person diary to a second-person exhortation, addressing her readers as comrades. Hathaway does the same aurally. On “The Ghetto,” he overlays ambient baby cries—his daughter Lalah—and street-corner banter, then coaxes handclaps that foreshadow the participatory call-and-response of his later live shows. Ric Powell’s liner-note description of the track as a “tour of the happier aspects” of Hathaway’s childhood neighborhood parallels Hansberry’s depiction of South-Side Chicago resilience amid segregation. Both artists stage community not as a romantic backdrop, but as active co-authors, blurring the lines between performer and audience.

Hansberry fused theology and radical politics, urging young writers to “write about the world as it is, and as you think it ought to be.” Hathaway answers with “Thank You Master (For My Soul),” a six-minute gospel meditation that coexists with “The Ghetto” on the same LP side. That juxtaposition refuses the false divide between sacred solace and secular critique, echoing Hansberry’s conviction that courage can be a devotional practice.

When Hathaway covers Simone’s “To Be Young Gifted and Black,” Powell notes he “adds a new message—a lament for the many young, gifted and Blacks who are trapped by lack of opportunity.” The performance extends Hansberry’s celebratory slogan into a blues-inflected realism, just as the book tempers hope with accounts of housing-covenant violence and McCarthy-era surveillance.

Hansberry’s collage technique aligns with the Black Arts Movement mantra “everything is everything,” a phrase participants used to signal that art, politics, and daily life were inseparable. Hathaway seizes that same phrase for his album title and opening lyric, translating literary collage into musical polyrhythm. Music scholars locate him as a central figure in 1970s soul precisely because he welded jazz harmony, gospel harmony, and blues phrasing into a unified theory of liberation. All About Jazz notes his fusion challenged critics who treated genre borrowing as one-way traffic from jazz to rock, insisting instead on bidirectional exchange among Black idioms.

Hansberry employs montage to disrupt linear American exceptionalism, while Hathaway employs harmonic shifts that thwart pop predictability. Both strategies qualify as aesthetic activism, as they compel the audience to practice flexibility, track multiple voices, and inhabit ambiguity. That sensory training becomes political preparation, teaching listeners and readers to decode propaganda and improvise a coalition.

Simone’s anthem became a soundtrack of marches, and Hathaway’s rendition circulates through reggae, gospel, and pop covers, amplifying Hansberry’s reach. “The Ghetto” was later sampled by hip-hop producers and reimagined by George Benson and Too $hort, transforming Hathaway’s street soundscape into a transgenerational reference. Likewise, Hansberry’s essays inspired theatrical revivals and influenced novelists and playwrights, including August Wilson and Suzan-Lori Parks. The pattern is identical: each work multiplies through reinterpretation rather than static memorial, confirming that radical art is a living commons.

The phrase “everything is everything” predates Hathaway, surfacing in Black Arts conversations as shorthand for holistic consciousness. By elevating it to album thesis, he foregrounds systemic thinking—poverty, joy, migration, romance, and protest all interlock. Hansberry’s collection operates on the same principle. Essays about Pan-African peace conferences sit beside childhood sketches, reminding readers that international freedom struggles and personal interiority are part of the same weave. Neither text allows the consumer to isolate vibes from politics.

Hathaway and Hansberry never met, yet their first major solo statements converse across page and groove. Both works employ montage to mirror the fragmented yet interdependent realities of Black America. Both yoke spiritual exaltation to material analysis, converting private testimony into communal ritual. Both insist that hope and heartbreak can share the same bar, the same paragraph, without resolution. Most crucially, both treat their audience as collaborators—Hansberry addresses “you, young, gifted and Black,” while Hathaway punctuates solos with crowd murmurs and everyday sound effects. The result is two debut works that behave less like introductions and more like open-source blueprints.

Listening to Everything Is Everything while reading To Be Young Gifted and Black reveals parallel cadences. Outside of piano vamp resolves just as a diary entry lands, a horn line echoes a staged monologue’s rising action, their synchronicity lies in a shared argument. To be young and gifted is not a guarantee of deliverance. To be everything is to recognize that love, study, struggle, and groove are indivisible. Hathaway supplies the soundtrack, and Hansberry the libretto; together, they craft a living syllabus for surviving America without surrendering imagination. Their works remind us that the path from block party to Broadway and from choir loft to picket line is a single braided road, still inviting us to march, dance, write, and sing alongside them.

phenomenal read. thanks for this great piece