The Quiet Double Standard Around Artistic Integrity

The double standard that makes Ravyn Lenae, Alemeda, and their peers explain themselves for chasing the same reach everyone else celebrates.

Eight months flew by before a TikTok mashup of Solange’s “Losing You” propelled it to the number five spot on the Hot 100, sending people into a frenzy, when Ravyn Lenae dropped “Love Me Not” back in May 2024. Coming from a woman who was once at the forefront of the real R&B scene, there’s now a perception that she’s traded in traditional sounds for the fleeting fame of TikTok, and that’s causing concern for those who still love HYPNOS two years on. Her authenticity is now being measured by her sound’s distance from her Steve Lacy collaborations, as if it’s a betrayal, and they’re acting like electro beats and classic soul on Bird’s Eye are diametrically opposed, instead of two ideas that were given time to grow on her.

Coming from someone who’s been making music since they were a teenager in Chicago, with a four year hiatus between her debut EPs, HYPNOS and the record in question, Bird’s Eye is basically a work about trusting her gut and not getting caught up in overthinking, and learning what pressure does to the music, but the backlash doesn’t care about any of that. The argument is all over the sound of “Love Me Not,” which is thought to be an indie-rock song with a B-52s vibe, its crossover appeal, the Coachella appearance, and Sabrina Carpenter’s tour all getting people worked up. They believe that somewhere along the way, she had to sacrifice something fundamental in pursuit of a bigger audience.

The music, though, tells a different story. The song “Skin Tight,” which was written with Steve Lacy a year back, started hinting at the crossover sound that was yet to come, and “Genius,” which kicks off the album, is straight out of her Chicago roots. “One Wish” is a heartfelt Motown-tinged duet with a distant father, featuring Childish Gambino, and has a reggae beat. The album bounces between electro-pop, throwbacks, and R&B and doesn’t apologize for any of it. Ravyn Lenae took her time, turned down the pressure, and developed her genre-defying sound in her twenties. She said that Bird’s Eye was about self-trust and ignoring analysis paralysis, and that she enjoyed making this record more than HYPNOS because he didn’t weigh himself down.

When Alemeda drops into the music scene, you can say she’s got Ethiopian roots, born in Ethiopia, but raised between there and Arizona, and she knocks out genre-bending pop-rock, alt-pop, drum’n’ bass, and UKG tunes that are all about the pain of break-ups and self-worth. Coming hustling over into the scene, her breakthrough was the drum ’n’ bass track “Gonna Bleach My Eyebrows” that was inspired by PinkPantheress, and “Post Nut Clarity” just carried on in the same vein. Well-known labels like TDE and Warner Music signed her in ’24 and dropped her EP FK IT, and by that time, she’d already made it clear that she didn’t want to be boxed in by R&B conventions.

The problem is, the music industry is still trying to force her there. Alemeda has spoken out about the anxiety she has that just one misstep will have her locked into the R&B category for life, not because her music has anything to do with R&B, but because she’s Black. Pop-rock, as she’s said, was such a white-dominated space that it felt like a private club that Black people couldn’t get into, and in the industry, anything Black and melodic is flattened into R&B or “urban.” It doesn’t matter if the music itself doesn’t sound that way. FK IT, however, is basically alt-rock with a raw edge, a punk attitude, and ethereal melodies. Warner signed her specifically because of their background in rock and pop.

TDE, who gave her four years to find her sound and told her they wouldn’t push her into the hip-hop or R&B moulds, still can’t shake the expectations that she’ll stay true to the style that the fans are used to. Alemeda herself confessed she suffered from imposter syndrome, releasing FK IT to prove to TDE that he music was real and substantial, and that she worried her new fans would think her music was too commercial. The label that’s also produced SZA and Doechii knew that letting a Black woman do her thing in the rock world meant giving her a lot of space to do that.

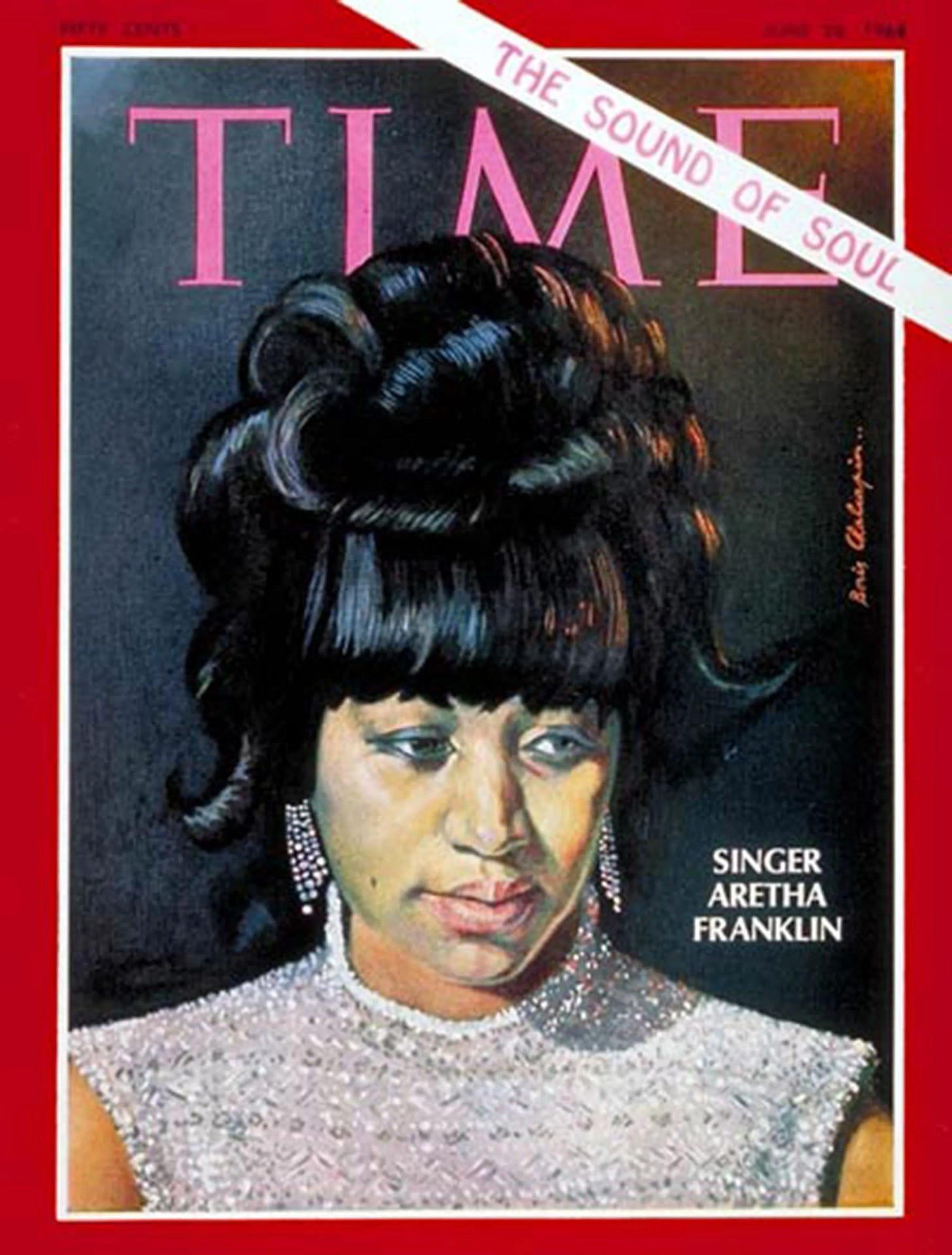

This discussion isn’t new. When Time magazine profiled Aretha Franklin in 1968, they laid down the law. The closer a Black artist gets to a “white” sound, the more they’re accused of betraying their heritage, and took the example of Dionne Warwick and the Supremes, literally, “Dionne Warwick singing ‘Alfie’? Impure!” and “Diana Ross and the Supremes recording an album of Rodgers and Hart songs? Unacceptable!” The Supremes weren’t called sellouts retroactively because Motown started crossing over into the mainstream. A 2012 humanities article looked at this as part of the ongoing debate about Motown and authenticity, and asks if the Supremes were indeed sellouts to the white community, and brings up their manager, Shelly Berger, who described them as “a white act” and said “it was understood that the Supremes’ audience was white.”

Whitney Houston was booed at the Soul Train Music Awards back in 1988 and 1889. Coming fast into a room where everyone already knows each other didn’t help. Al Sharpton even called her “Whitey” Houston, which didn’t sit well. The audience started booing when her name was announced as a nominee, and it wasn’t because she won anything, or didn’t, but because they said she had sung too much of a white sound and lost her roots in the process. Her self-titled album in 1987 went on to sell 25 million copies, followed by another album, and between those two, she had seven consecutive number-one hits. Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson, and Jody Watley were also up for awards that year, all of them crossover acts, but the crowd really turned on Whitney. Anita Baker won Best R&B Urban Contemporary Single by a Female in ’89, and she had been absolutely killing it at that point. It wasn’t because Anita didn’t have the same commercial success, but because Whitney’s takeover of the pop charts made it look like she’d abandoned something fundamental.

She fired back on The Arsenio Hall Show in 1991, saying that the criticism was based on her singing too much of a white sound, but she’d grown up on Soul Train just like any other Black kid. She believed she was doing what God wanted her to do, and using the talents he gave her, but that booing still hurt her. Kirk Whalum, her saxophonist back then, said she never fully bounced back from the scarring and that it was one of the things that was still weighing on her mind when she eventually passed. When watching the documentary Whitney: Can I Be Me, it’s clear that Whitney Houston’s early image and sound were, to a large extent, manufactured by the music industry, and that the criticism she received wasn’t really because of anything she did, but because of the misconception that when Black artists try to crossover to the white market they need to essentially ‘dilute’ their Blackness to suit the commercial appeal of radio. Clive Davis made the point that they had to shore up her base in the Black community for her third album, but didn’t say that the Soul Train booing was the reason why she couldn’t get a break. Well-known to be the biggest Black artist of the year, Soul Train awarded her Female Artist of the Decade in 2000, proving that the stigma that stuck to her wasn’t due to any lack in her performances.

The issue of genre policing is basically another way of saying race policing, because, SZA said in 2024 that she’s been locked into the R&B category purely because she’s Black, that it’s a reduction of her musical talents and doesn’t let her have space to be anything else, whereas Justin Bieber isn’t classified as an R&B artist just because he makes R&B songs. SZA wants her hits “F2F,” “Nobody Gets Me,” and “Kill Bill” to be regarded as what they are, not as R&B by default, and is echoing what Chlöe has also said. That R&B and “urban” turn into catch-all labels that flatten the beautiful sound of Black artists and shut down the idea that Black artists can be anything else. When Alemeda says that Black artists get classified as R&B artists even when they make completely different kinds of music, and when Ravyn Lenae gets called out for ‘abandoning R&B’ because she started to make indie rock-influenced pop, they’re running into the same barrier. That barrier says that Black women in music are seen as being in one particular category until they prove they can be in another, and then that very proof is used to disqualify them as inauthentic.

Misogynoir is a word that was coined in 2008 by Moya Bailey to talk about the ugly combination of anti-blackness and sexism directed at Black women, especially in visual and digital media. It’s what gives rise to the devastating accusations that Black women artists are too promiscuous, too poppy, too commercial, or too tame, and land hardest on the careers of Black women trying to make it to the top. When Ravyn Lenae drops Bird’s Eye and Alemeda signs with Top Dawg Entertainment, the drama is not just about musical taste. It’s about the way that Black women are perceived when they land a major-label deal, get a high-profile feature, or smooth out their sound. Well-known male artists and their white counterparts are showered with praise for being ambitious and “growing” in their careers, but Black women, especially in the music industry, are asked if they’re still “real.”

The double standard is quite clear; artistic integrity in Black women becomes a leash. It’s like, they’re told that staying small, niche, broke, or stuck in one genre is what is considered genuine, and that straying from that path is a moral failing, not a career move. Whitney Houston’s crossover in the late eighties, which wasn’t a betrayal, was basically an example of this phenomenon. The pop scene at that time was heavily influenced by Black musical innovations, the synthesized pop of the Pointer Sisters, the funk that powered the era’s biggest hits, and so on. When people said that Whitney was singing too white, they weren’t attacking the music, but they were saying that she had to have compromised her artistic vision to get through to the mainstream, and that Black women in general can’t have mainstream success without watering down their sound.

The situation with Ravyn Lenae and Alemeda is hauntingly similar. The genres, the jabs at chasing TikTok fame, and the claim that they’re disowning something essential are all pinned on the idea that Black women are in debt to their “roots.” Or what we consider to be their true place within the music landscape. When Ravyn Lenae dropped “Love Me Not,” she had a decade of industry experience behind her, coming rushing from tours with SZA and Noname, collaborating with Steve Lacy and Monte Booker, and dropping EPs and albums that ended up on the best-of lists. She took four years out from the scene, mulling over what she wanted to say to the world. Well-known for not chasing fleeting fame and instant success, she’s always spoken out about the importance of being patient and trusting her gut. Bird’s Eye is the embodiment of this approach.

Alemeda, on the other hand, grew up being banned from music and TV, stumbled upon it by sneaking onto a clock radio, got kicked out of her house at seventeen, worked graveyard shifts at an airport, and then fought tooth-and-nail for four years under Top Dawg Entertainment to find her voice. The sound that is FK IT is the result of that arduous process. Whitney Houston, with one of the most remarkable voices in music history, unapologetically made huge, ambitious pop records that helped catapult Black vocal traditions into the mainstream, and all three of these women made calculated decisions about their careers and were consequently accused of selling out.

Well-known criticisms of Black woman artists, that they should stick within the lines they’re given, that crossing over is suspicious, and that artistic integrity is all about rejecting anything that might bring financial or artistic success, are unfounded. Pop has long been a crucible for Black innovation, R&B has always been adaptable, and genre boxes are nothing more than corporate tools. The expectation that Black women have to justify their need for more, such as more exposure, more creative freedom, and more money, is a brand of gatekeeping that severely limits their careers, stifling them.

Ravyn Lenae doesn’t owe us HYPNOS forever, Alemeda doesn’t owe us R&B, and Whitney Houston didn’t owe anyone anything except the voice she brought. Artistic integrity shouldn’t be a straitjacket around Black women’s necks when they decide they want more.