VIBE × Rolling Stone and the Rise of Captured Identity (When Culture Gets Consolidated)

How the union of two iconic brands mirrors the absorption of radical cultural voice into corporate‑media logic.

When Penske Media Corporation announced in mid‑October 2025 that VIBE would “join forces with Rolling Stone,” the news marked more than another media merger. It brought together two magazines born in different eras, each rooted in distinct cultural movements, and each originally launched with an oppositional or disruptive sensibility. Rolling Stone began in San Francisco’s countercultural ferment of 1967; VIBE, launched by Quincy Jones and Time Inc. in 1993, became an authoritative chronicle of hip‑hop and R&B. The merger, presented by Rolling Stone CEO Julian Holguin as a way to “level up the publication’s hip‑hop and R&B coverage”, also led to layoffs of VIBE staff and signaled a reconfiguration of the brand around video, podcasts, long‑form journalism, and experiential opportunities.

The consolidation raises questions about how corporate logics can absorb radical cultural projects and repackage them for commercial gain—what philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò calls Elite Capture. According to Táíwò, Elite Capture occurs when “the advantaged few in a group steer the resources and political direction of organizations or movements toward their narrower interests and aims.” Examining Rolling Stone and VIBE through this lens reveals how their merger reflects the absorption of oppositional cultural voices into a consolidated corporate media landscape.

Jann Wenner and music critic Ralph J. Gleason founded Rolling Stone in San Francisco in 1967. Its first issue featured John Lennon and included Wenner’s statement that the magazine aimed to reflect “the changes in rock and roll and the changes related to rock and roll.” Although Rolling Stone materialized from the 1960s counterculture, it consciously distanced itself from the radical underground press; early contributor Susan Lydon said the magazine sought to combine the spirit of a newspaper with more traditional journalistic standards. As historian Jessica Hyman notes, Wenner instructed his staff to avoid “radical political topics and statements in order to bring in advertisers,” and the magazine’s early political articles offered superficially anti‑war or pro‑marijuana sentiments without providing readers with tools for activism.

This cautious commercial orientation allowed Rolling Stone to root itself in the counterculture while sidestepping the “dangers of being a countercultural magazine,” helping it secure advertising revenue. Over the next two decades, Rolling Stone moved its headquarters from San Francisco to New York and shifted toward celebrity‑driven entertainment coverage. The magazine’s pivot toward mainstream culture—covering film stars and fashion while featuring gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson’s political reporting—illustrates how an initially oppositional project can become integrated into commercial media.

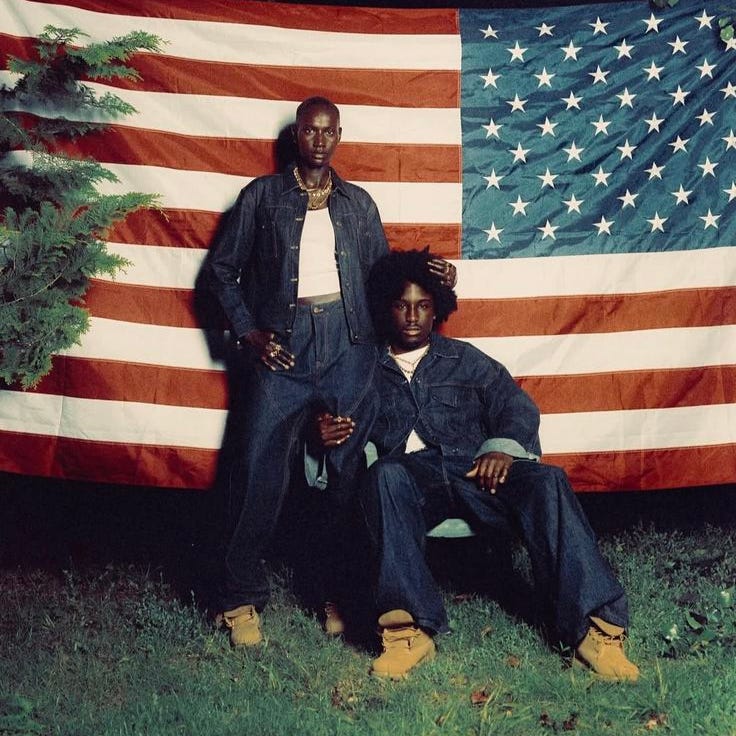

VIBE’s origins reveal a different but similarly complicated relationship with mainstream media. In 1993, Quincy Jones, then the world’s most powerful Black record producer, launched VIBE with Time Inc. after a test issue in 1992. The magazine aimed to be a “Rolling Stone for the hip‑hop generation”—sexier and more polished than rival rap magazines—and to showcase what early staff members called a “new Black aesthetic” that linked hip‑hop to broader cultural and historical currents. VIBE’s pages profiled artists such as Tupac Shakur, Snoop Dogg, and Ms. Lauryn Hill and featured articles that broke news or even inspired films like The Fast and the Furious.

The magazine gave Barack Obama cover space in 2007 and showcased Black intellectuals like Cornel West while advertising black‑owned fashion labels. It allowed black writers and photographers to represent hip‑hop artists without perpetuating the stereotypes of mainstream media. During the 1990s, the magazine exuded confidence and glamour—“like the print equivalent of a Hype Williams video,” as The Guardian described. Yet VIBE’s success also depended on corporate backing. Its early editorship came from white, Vogue‑trained Jon Van Meter, and by the mid‑2000s, the brand diversified into awards shows and reality programs, diluting its editorial distinctiveness. Private‑equity firms purchased the magazine in 2006 and again in 2013, and print operations ceased in 2014. These ownership changes foreshadowed the magazine’s eventual absorption into Penske Media’s portfolio.

When Penske Media announced the VIBE–Rolling Stone merger, Holguin promised that Rolling Stone would invest in VIBE across video, podcasts, long‑form journalism, social media, and experiential opportunities and that VIBE would print special collector’s editions and produce a new interview series. VIBE’s longtime editor‑in‑chief, Datwon Thomas, was moved into a strategic‑advisor role, and new hires were announced, but several women journalists of color were laid off. The merger narrative thus combined the language of investment and growth with actual workforce precarity. Holguin framed the consolidation as continuing VIBE’s mission while leveraging Rolling Stone to “amplify its presence.”

However, because the same corporate parent, Penske Media, controls both magazines, the merger effectively concentrates control of mainstream rock and hip‑hop coverage under a single executive structure. Táíwò’s description of elite capture precisely illuminates this dynamic: elites “steer the resources and political direction of organizations or movements… toward their narrower interests and aims.” In this case, a private media conglomerate repackages Black cultural capital within the infrastructure of a general‑interest entertainment brand. The radical potential of VIBE as a platform for Black writers and artists is constrained by the commercial imperatives of Rolling Stone and Penske Media.

Elite capture helps explain why the merger may blunt the disruptive capacities of both magazines. Rolling Stone’s countercultural authenticity was already eroding due to its calculated avoidance of radical politics and its transformation into an entertainment platform. Its parent company is now a central player in celebrity journalism, event production, and digital advertising. Bringing VIBE into this fold risks turning hip‑hop’s oppositional practices into marketable lifestyle content rather than platforms for critique. Even if Rolling Stone expands its hip‑hop coverage, the editorial tone may reflect the tastes of a professional managerial class rather than the lived experiences of marginalized communities—an example of the phenomenon Táíwò identifies when he notes that identity politics can be deployed to serve the interests of elites rather than the vulnerable people it purports to represent. The layoffs of Black women journalists during the merger not only reduce the number of Black voices shaping coverage but also underscore how diversity initiatives can be sacrificed to cost‑cutting and branding strategies. Meanwhile, Rolling Stone’s existing leadership benefits by gaining credibility in hip‑hop culture and expanding advertising prospects. The communities for whom VIBE served as a cultural record risk losing a dedicated space where Black fashion, politics, and intellectual life are centered.

The consolidation also reflects a broader trend in contemporary media: the increasing commodification of identity and culture. Rolling Stone and VIBE, once symbols of counterculture and black cultural confidence, are now brands to be cross‑marketed across podcasts, streaming services, and merchandise. In Táíwò’s account, this rebranding is exactly how “identity politics… is weaponized to split people into ever narrower categories that hamper movements for racial and social justice.” Under corporate ownership, radical expressions of identity can be stripped of their political substance and turned into consumable images. When hip‑hop culture becomes a line item in a conglomerate’s portfolio, the economic returns flow to shareholders rather than to communities that created the culture. The merger thus exemplifies the way cultural capital rooted in black communities is translated into financial capital for corporate elites—an example of racial capitalism.

A genuinely transformative media approach would resist such elite capture by restructuring both ownership and editorial practices. First, rather than consolidating into conglomerates, hip‑hop and countercultural publications could experiment with cooperative or nonprofit ownership that keeps decision‑making power among writers, artists, and the communities they serve. Models such as worker‑owned newsrooms, membership‑based platforms, or community‑funded cooperatives would help ensure that resources and editorial direction are not captured by a small elite.

Second, editorial practices should center the voices of marginalized communities and foster what Táíwò calls “a constructive politics of radical solidarity”—coverage that builds alliances across identities and links cultural expression to struggles against racial capitalism, patriarchy, and colonialism. Rather than relying on celebrity access and branded events, such media would invest in investigative reporting on issues like housing, policing, and environmental justice; amplify grassroots artists; and provide platforms for Black feminists, queer activists, and working‑class writers to shape the public agenda. Third, transparency about advertising relationships and funding sources would help guard against conflicts of interest and the quiet influence of corporate sponsors.

In short, the VIBE × Rolling Stone merger is a powerful case study in elite capture. It brings together two magazines whose histories illustrate how radical or oppositional cultural practices can be commercialized and redirected toward elite ends. Rolling Stone’s transformation from counterculture chronicler to mainstream entertainment brand, and VIBE’s evolution from hip‑hop’s authoritative voice to a digital lifestyle platform, set the stage for their absorption into a single corporate entity. While the merger promises investment and expansion, it also risks further diluting the magazines’ radical roots, marginalizing Black creative labor, and reinforcing corporate control over cultural narratives. Resisting this trend will require building new media institutions grounded in solidarity, collective ownership, and accountable storytelling—media that not only represent marginalized identities but also challenge the power structures that seek to capture them.

Hi, Brandon O'Sullivan here! Thank you for reading this piece. As you may know, the Shatter the Standards’ brand and beyond is about championing Black art and uplifting these voices while they’re still present. All that said, also support these individuals and publications that are putting in the work (if I miss anyone, I genuinely apologize).