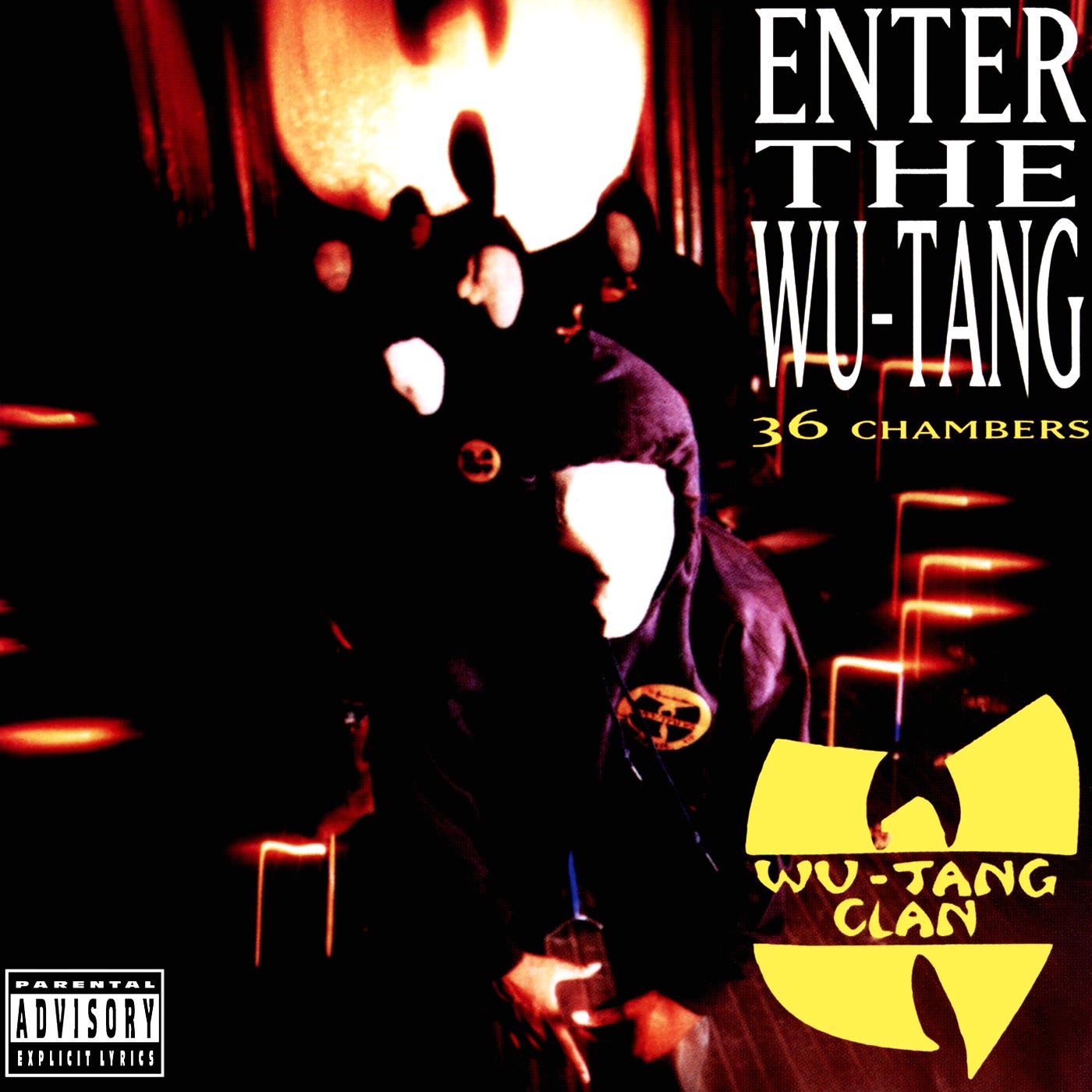

Wu-Tang's Cultural Revolution in Music

Dive into RZA's journey from martial arts movies to shaping the Wu-Tang Clan's groundbreaking sound with Enter the Wu-Tang.

A man who’s been heavily influenced by the cultural shifts of 1973, Robert Diggs discovered his life’s direction through hip-hop and kung fu. It was in that year that he celebrated his fourth birthday and witnessed the martial arts film Enter the Dragon, which told a tale of racial unity between actors Bruce Lee, John Saxon, and Jim Kelly. This was also when DJ Kool Herc rocked a back-to-school party using two copies of James Brown’s LP to build an irresistible dance number from “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose.” These events marked Robert’s early encounters with diverse cultures merging—something that would profoundly shape his future ventures.

As an emerging rap enthusiast who spent much time traveling around America during childhood, Robert found himself particularly drawn towards New York block parties, where he first fell for this music genre. At eleven years old, he was already caught up in rapping rivalries across East Coast cities. Staten Island became part of familiar territory due to family links there; it brought him closer to Russell Jones—his cousin with whom he’d watch kung fu movies at run-down theaters in Times Square. Their routine involved seeing films followed by practicing moves on each other before hopping on trains back home, only to continue their mock fights and engage in impromptu rap battles with local MCs.

Two motion pictures had significant influence over young Diggs; Enter the Dragon and The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, directed by Lau Kar-leung, impacted him deeply, providing non-Western perceptions about life.“It was through these films that I felt seen,” says Diggs while explaining how they ultimately led him towards valuing multicultural collaboration against oppression—just like characters Lee, Saxon, and Kelly were doing inside play reels. His exposure to amalgamating martial arts ideologies along Five-Percenter Muslim doctrines prevalent in New York led him to team up with Jones and another cousin, Gary Grice, to form a rap band named Force of the Imperial Master. The group later transitioned into ‘All in Together Now’ within a year.

Parallelly, Diggs also established D.M.D. Posse comprises close aides from his Park Hill neighborhood situated at Staten Island, including Clifford Smith Jr., Lamont Hawkins, Jason Hunter, and Corey Woods. Following his short solo music venture leading to the creation of ‘Ooh I Love You Rakeem,’ Robert moved temporarily to Steubenville, Ohio, gaining opportunities for living with his mother.

Diggs’ initial missteps in petty crime, leading to his arrest for allegedly injuring someone with a gunshot, threatened an early end to his budding rap career. Facing potential imprisonment of eight years may have buried his music dreams forever. But having acquired another opportunity, he became resolved to improve both his and the lives of those around him.

While sojourning in Ohio, Diggs struck up a friendship with Selwyn Bougard—who would later be known as 4th Disciple—and their partnership produced music recorded amidst humble beginnings: demos from Bougard’s grandmother’s basement using improvised equipment. A microphone hung on wire hangers with protective socks signified the unpolished yet energizing environment that fueled Diggs’ sense of purpose.

Returning to New York in 1991 ignited fresh ambitions for Diggs, amalgamating friends sharing interests like hip-hop and kung fu under one entity—now christened RZA. He ushered others into this new league: Jones transformed into Ol’ Dirty Bastard; Grice was now GZA; Smith morphed into Method Man; Hawkins took up U-God’s mantle, while Hunter responded as Inspectah Deck. Woods adopted Raekwon the Chef’s persona, whereas Coles assumed Ghostface Killah’s identity. Later, Masta Killa, born Jamel Irief, joined the assembly led by RZA. Incorporating inspirations from favorite cinematic experiences like Shaolin and Wu-Tang (1983), this group reincarnated Staten Island into their unique ‘Shaolin,’ thus marking the birthplace roots of the Wu-Tang Clan.

At its inception, Wu-Tang entered a rap industry dominated heavily by jazz-infused East Coast performances alongside West Coast G-funk displays—making it challenging for alternate modes of creative expression to find a voice within mainstream circles. Undeterred by prevailing trends, though resiliently crafting music aligned with personal ethos, was RZA. His style, mirroring subterranean shadows and the hardness of a chest-pounding roundhouse kick, was cultivated using hand-me-down equipment such as an Ensoniq keyboard sampler previously owned by RNS—a fellow Staten Island group member from the U.M.C.’s.

Recording sessions for Wu-Tang commenced in Brooklyn at Firehouse Studios, affordable yet not ideally designed for larger vocal groups. Their initial session, funded mainly through quarters, amounted to $300; their setup consisted of a living-room-connected walk-in closet functioning as a recording booth that barely accommodated the entire ensemble. Perfections sought in creations resulted in repeated recordings with verse rearrangements—evident when lyrical expressions raised by various members came together like puzzle pieces finding home: Inspectah Deck’s sharp lyrical cuts against Raekwon and Method Man’s flair; U-God’s suave, psychotic lines folding into O.D.B.’s orchestrated tumult; Ghostface amplifying precision amidst RZA and GZA’s staunch support.

The song “Protect Ya Neck” showcased collective talent without any overarching theme besides proving individual microphone mastery. It served as a warning about an impending shift towards darker tones within New York rap verse, signaled via distortions culled from James Brown’s band sample, The J.B.’s—beautifully converging to manifest years of shared experiences spanning joy, pain, and sacrifice embedded within their songs, beautifully fusing to manifest years of shared experiences traveling pleasure, pain, and sacrifice embedded within their songs.

After releasing their single “Protect Ya Neck” on Wu-Tang Records in the closing month of 1992, it rapidly attracted attention within subterranean music circles. Each record sale included RZA’s contact information as an invitation for larger industry figures to make direct contact. This savvy move eventually led to a group contract with Loud Records and the beginning of work on their debut album, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). Despite this progress, financial hardships remained, and several band members resorted to selling illicit substances to afford studio time at Firehouse.

Resource limitations called for unconventional approaches when recording began. The distinct gritty aura associated with 36 Chambers sprouted from rudimentary technology in the studio and harsh song transitions that were unavoidable rather than stylistic choices. Fusing samples from soul, funk, and jazz records, he admired and adored martial arts films was central to RZA’s strategy. It resulted in a cinematic layering over every beat without forsaking its raw charm originating from lo-fi production.

Unconventional techniques extended beyond just sampling; during recording sessions for “Bring da Ruckus,” piano excerpts sampled from Dramatics’ “In the Rain” play alongside a unique snare sound made by repeatedly hitting a paint bucket mic’d up by RZA himself. In another example, “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing ta F’ Wit,” the theme music borrowed from the classic cartoon Underdog is slowed down and overlayed onto drums sampled Joe Tex & Biz Markie tracks, creating an impressively powerful effect.

Further reflecting his love for film dialogue are seven out of thirteen songs featuring snippets lifted directly off screenplays often situated either upfront or subtly hidden within chorus sections—six specifically borrowing lines spoken by characters straight out of Shaolin & Wu Tang feature films playing alongside others such as Five Deadly Venoms (“Da Mystery of Chessboxin’”) or Ten Tigers From Kwangtung (“Bring da Ruckus”).

These tracks unfold like a well-scripted movie, as in “Bring da Ruckus,” where Ghost, Rae, Deck, and GZA skillfully utilize references from personal histories to trending news and popular culture to outshine each other during their respective verses metaphorically. The dramatic effect is further amplified with the incorporation of dialogue samples.

Even though there existed an evident varying range of personalities all making their debut recording, every distinctive voice finds its unique space within the structure. Though he’s the one leading this musical project, it was his decision not to hog the limelight that stands out as one of the most significant aspects of 36 Chambers—RZA instead decides to let each member shine on carefully tailored soundtracks that best complement them.

For instance, O.D.B.’s distinct vocal style fits perfectly onto “Da Mystery of Chessboxin’,” which was sampled off a creaky mandolin, or even Method Man’s memorable line “cash rules everything around me” feels right at home amongst dreamy piano keys playing through “C.R.E.A.M.” Each uniquely different piece seamlessly fuses forming an exclusively unified body—much similar to piecing together fragments of some ancient artifact.

Each member had unique moments that showcased their strengths throughout 36 Chambers. U-God amazed by his powerful four-bar intro in “Chessboxin’,” disregarding his conviction for firearm possession days earlier. “Can It All Be So Simple” presented Ghostface and Raekwon’s incredible chemistry, which later blossomed in Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… The track echoed tales of lost innocence, dreams interrupted by phone calls from friends behind bars, all while being held captive by a haunting Gladys Knight & The Pips sample.

Then there was Method Man, whose versatility saw him spit on various issues—creating spectacular verses spanning over three-and-a-half minutes on his self-titled song—all while enjoying White Owl blunts. Ultimately, the diversity in rhyme styles woven together by RZA’s willpower alongside newfound kin gave rise to an emotionally profound masterpiece, excluding none of its production flaws or musical imperfections: They were just as formidable individually as collectively.

Its LP release on November 9th seemed precision-timed, and it immediately made waves in the scene, peaking at number 41 on Billboard’s Top 200 while amassing sales of around thirty thousand units within the opening week alone. The stature and influence of this enigma soon gained steady footing as its popularity grew organically.

By mid-1995, their Platinum milestone firmly established them among New York hip-hop’s challenging forces; they were ready to upset any opposition daring enough to challenge their musical palette. This stepping stone led directly into a relentless surge for solo pursuits from members such as Cuban Linx with GZA’s Liquid Swords, followed closely by Method Man’s Tical and Ghostface Killah’s Ironman. These efforts further solidified Wu-Tang Clan’s heritage before we crossed over into a new millennium.

The rapid progression didn’t stop there: from striking gold with movie scores beginning with Ghost Dog: The Way of Samurai (released in ’99) to conceptualizing a video game that, despite getting shelved, became infamous novelty fodder circling tales about Wu-Tang Clan; all these factors amplified their East-meets-West philosophy which went onto being adapted into books that sketched out narrative skits for Chappelle Show.

Depicting the life they knew from Staten Island’s perspective, nine individuals joined forces to form an unbreakable bond. Their shared experiences and philosophies revolving around deep mental exploration and appreciation of evanescent fried food aromas wafting through Brooklyn’s Palmetto Playground are what made them a unit. But beyond their brotherhood, their influence extended into pop culture significantly.

Their creation inevitably made waves across New York rap circles, leading hard-core rappers like Nas, Mobb Deep, and Notorious B.I.G. followed suit almost religiously for nearly three decades since then—solidifying Wu-Tang Clan’s legacy within hip-hop music history books. Thus commenced the Tao of Wu—an unyielding code that has continued shaping rap purists’ work across collectives even after three decades.