Milestones: Diana by Diana Ross

Diana endures not merely because its singles remain DJ staples, but because the record captures an artist in perpetual motion.

Diana Ross looked across the final months of 1979. She saw a churn of change, as disco faced hostile headlines, Motown pivoted toward younger signings, and she herself had not cracked the U.S. Top 10 since “Theme from Mahogany” four years earlier. Yet rather than retrench, she sought the shock of the new, telling confidants she wanted to “turn her career upside down and have fun again,” a phrase that lodged in the subconscious of the musicians she was about to hire.

Those musicians were Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards of Chic, then revered for the aerodynamic funk of “Le Freak” and “Good Times.” Before any tape rolled at Power Station in New York, Rodgers and Edwards conducted a two-day oral history with their prospective vocalist, quizzing her about fame, family, loneliness, and laughter; the answers became melodic prompts for the album that would simply be titled Diana. Ross arrived eager to cede authority on the groove but determined to keep the final word on presentation, an agreement that would prove provisional.

Tracking began in November 1979 amid weathered anti-disco sentiment, yet the songs Chic crafted were almost defiantly effervescent: lean eight-bar vamps, pinwheeling string stabs, syncopated hand claps, and basslines that flicked like jump ropes. “Upside Down,” “Have Fun (Again),” and “Tenderness” underscored a manifesto of self-authorship; Ross’s libretto floats through love’s contradictions with sly cadences, her voice skating just behind the downbeat to leave Chic’s rhythm section room to strut.

The fault line opened after rough mixes were delivered to Motown in February 1980. Label founder Berry Gordy reputedly snapped, “This isn’t a Diana Ross record,” balking at the extended instrumental breaks and recessed vocals. Without notifying Rodgers or Edwards, Motown’s chief engineer, Russ Terrana, was instructed to speed up the tracks, trim away instrumental codas, and bring Ross’s leads to the forefront; Ross re-cut several vocals to fit the brighter tempos. When the producers heard the finished master, they threatened to pull their names, but Motown held firm, wagering that Ross’s profile would carry the revision to radio. The resulting tension, artist and label on one flank, auteurs on the other, became lore long before anyone dropped a stylus on side A.

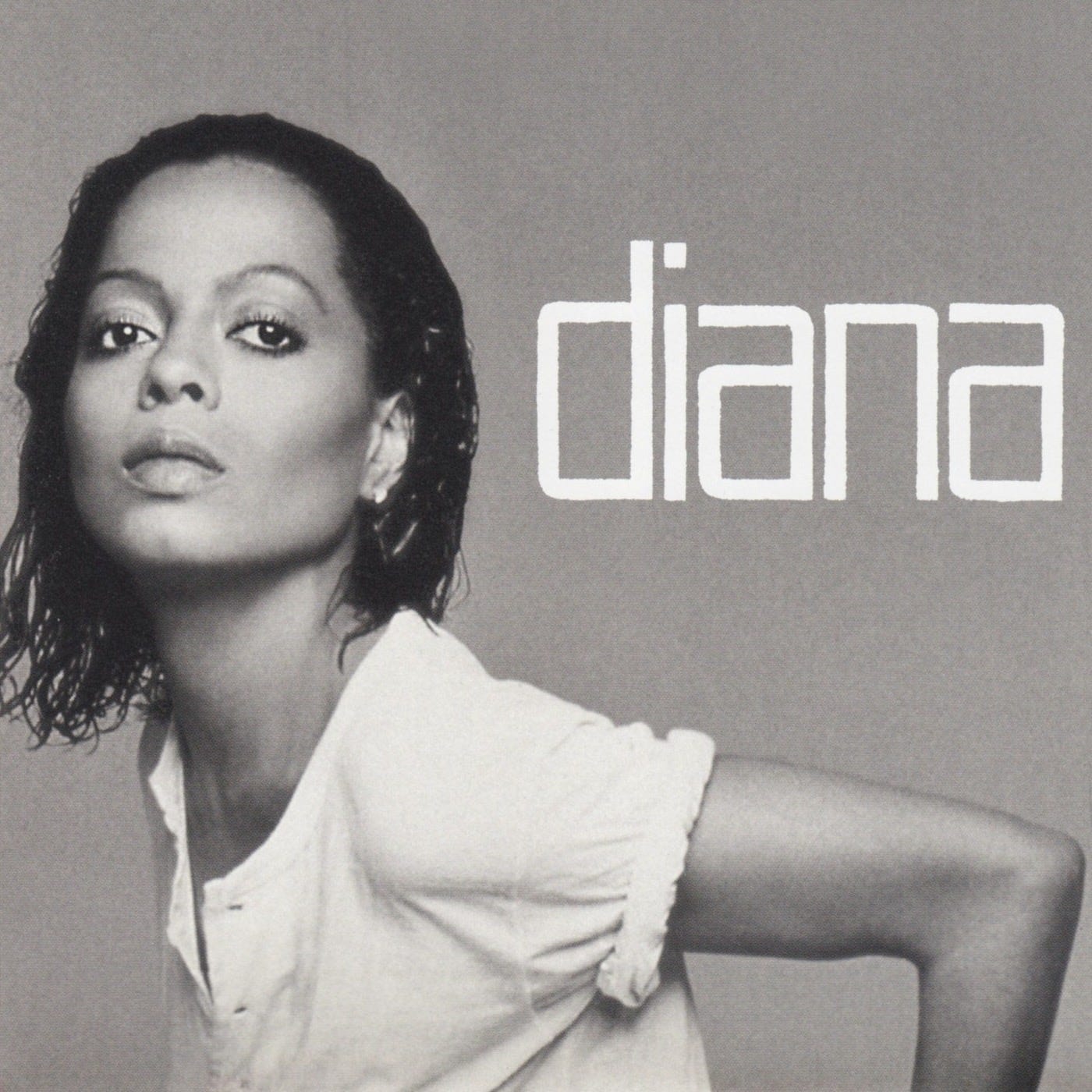

Diana arrived in a sleeve shot by fashion photographer Francesco Scavullo; Ross wears a simple white tee and borrowed jeans from supermodel Gia Carangi, cropped so tight her face is half-visible, the lowercase title whispering modern minimalism. Visually, it telegraphed distance from the sequined Supremes and the chiffon of Lady Sings the Blues—this was Ross unvarnished, ready for the club and the street in equal measure.

“Upside Down” opens with Bernard Edwards’s bass surfing the root note before slaloming into double-stop flourishes; Rodgers answers with clipped guitar up-strokes that anticipate every syllable Ross tosses. She narrates a romance spinning out of its axis (“Respectfully I say to thee, I’m aware that you’re cheating”), yet the energy never wilts, matching the dancefloor logic that anguish can still move feet. The single vaulted to number one across pop and R&B charts and dominated airwaves deep into autumn, giving Ross her first cross-format smash of the decade.

If “Upside Down” reasserted her commercial heft, “I’m Coming Out” redrew her cultural map. Rodgers conceived the hook after encountering a restroom packed with Diana Ross impersonators at Manhattan drag club the Gilded Grape; he realized that for many queer fans Ross already symbolized liberation. He and Edwards embedded triumphant horn fanfares that nod to Stax soul while Ross repeats the revelatory mantra with quickening urgency. Initially, she feared the lyric could be read as a literal confession, but Rodgers convinced her its broader proclamation of self-ownership would resonate. It did: the song became a Pride parade mainstay, later propelled into hip-hop memory when the Hitmen looped its brass line for The Notorious B.I.G.’s “Mo Money Mo Problems,” introducing a whole generation to Ross’s celebratory bravado.

Elsewhere, the record strikes a balance between exhilaration and introspection. “Have Fun (Again)” flickers with rim-shot percussion and octave-leaping bass, Ross coaxing herself to “break down those doors” of emotional austerity. “Tenderness” slows the pulse, with strings sighing behind lyrics that argue gentleness as a radical act in romance, while “My Old Piano” weds vaudeville imagery to a percolating Chic rhythm, cheekily turning a Steinway into both a dance partner and a confidant. Across the eight-track set, Ross experiments with vocal placement, sometimes singing in a hushed, near-whisper, and sometimes multiplying herself into layered choirs, mirroring the album’s subtext of multiplicity: diva, mother, entrepreneur, icon.

The commercial impact was instant, as Diana became the best-selling studio album of her career and remained on the U.S. charts for a whole year, vindicating the Terrana remix in the eyes of executives while proving Ross could inhabit Chic’s contemporary pulse without forfeiting signature glamour. It bridged disco’s four-on-the-floor insistence with emergent post-disco polish, sketching a template later adopted by Janet Jackson, Madonna, and scores of house vocalists who prized clean rhythm guitars and foregrounded female agency.

The record’s legacy is inseparable from its dialogue with marginalized listeners. Long before corporate Pride campaigns, “I’m Coming Out” offered Black LGBTQ audiences a mirror in a pop universe that rarely acknowledged them; Ross became an unwitting ally, her concerts suddenly thronged by rainbow banners. The track’s enduring presence at weddings, victory speeches, and transition celebrations underscores how a lyric born in a drag-club epiphany transcended its moment to articulate an elastic, renewable joy.

The dispute over authorship, however, refused to vanish. Bootlegs of the original Chic mixes circulated for two decades, prized for deeper low-end and longer instrumental stretches. In 2003, Motown allowed Rodgers to restore those versions for a deluxe CD, and in 2017, the Diana—Original Chic Mix surfaced on pink 45-rpm vinyl, finally allowing listeners to contrast the competing aesthetics: Chic’s unfiltered club minimalism versus Motown’s pop-radio concision. The existence of both editions renders Diana a case study in late-industrial pop production, exposing how questions of market positioning, label identity, and artist autonomy intersect on master tapes.

As decades pass, Diana endures not merely because its singles remain DJ staples, but because the record captures an artist in perpetual motion—rehearsing freedom, revising her sound, and resisting the nostalgia that commerce often foists upon veterans. The partnership with Chic briefly aligned three seismic forces—Ross’s charisma, Rodgers and Edwards’s architectural funk, and Motown’s distribution muscle—only to fracture under the weight of divergent priorities. Out of that friction came a bright, lean album whose pulse still feels current, reminding every listener that reinvention is rarely polite and almost always worth the risk.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)